Giving it to you straight: The discreet art of Jerry Desmonde

A great comedy straight-man, or straight-woman, is a discreet magician. They do not just misdirect the audience away from their tricks, but also from themselves. There is never any final white-gloved flourish, nor any spot-lit smiling bow. They work under cover, in plain sight.

The straight one is not merely a comic feed. That is an art in itself, requiring fine timing, but the skill of a straight one is up on another level entirely.

The feed sets up comic lines. The straight one also shapes a relationship.

He or she creates the reality within which the comic can thrive. They provide the gravity that keeps the other one grounded.

No one was such a master of this art than Jerry Desmonde. Working with some of the best comic performers of his time, he made them all seem even better.

The one unfortunate consequence of this was that, by ensuring the spotlight kept shining on the one standing by his side, he has himself been consigned to the shadows. While this is unsurprising - there are few surer ways to go under-appreciated than by excelling at subtlety and selflessness - it is nonetheless unjust, because, if you really admire great comedy, his special craft is something that merits your respect.

Bob Hope called him 'the best straight man in the business', and he was almost certainly right. He tended to play stern authority figures - fathers, teachers, employers, officials and other assorted éminences grises - who in a technical sense served comics like sharpeners serve knives, and in a dramatic sense helped humanise their humour.

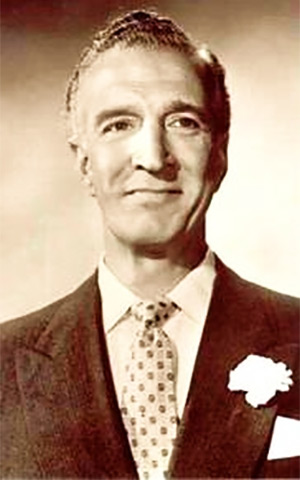

Those assured performances were the product of decades of dedication. Born James Robert Sadler, on 20th July 1908 in Linthorpe, Middlesbrough, he had been working regularly on the stage since the age of fourteen, when he joined the family act, The Sadler Elsie Four, after his older sister eloped (he had, initially, to don a dress and wig and play her parts).

Going solo two years later (having grown too long in the leg and nose to keep passing off the appropriate feminine pose), his plan was to become 'a serious actor who could speak Southern English as well as other dialects'. He succeeded to the extent that, after getting noticed playing a number of urbane young men in evening dress for the West End specialist C. B. Cochran, Noël Coward added him to the supporting cast for the much-praised revue This Year Of Grace, which toured parts of the US before opening on Broadway during the autumn of 1928.

Upon his return to England the following year, he assumed the stage name of Jerry Desmonde (adopted from a debonair character in a play of the time called The Under Dog by Walter Howard) and started stretching himself by combining intense spells in local repertory companies with the odd collaboration in variety. Tall, good-looking and blessed with a powerful voice, he was an adaptable performer, able to flit freely from beaming benignity to moody malevolence to fit the rich mixture of heroes and villains that he was offered, and he also seemed a natural master of ceremonies, exuding an air of assured bonhomie whenever he was required to engage directly with an audience.

He spent the first half of the 1930s working alongside his brother Jack (who was often billed as 'Britain's Maurice Chevalier'). They performed as a double act - usually called 'Jack and Jerry' but sometimes 'The Desmonde Brothers' - which saw them strumming guitars and banjoleles, doing the odd tap dance and sharing a few songs and comic dialogue.

Having married the dancer and singer Peggy Duncan in 1930, he teamed up with her on stage in the middle of the decade as 'Peg and Jerry', touring the variety theatres of her native Scotland for the next seven years - interrupted very briefly by a spell of wartime service in the RAF, from which he was invalided out after just ten weeks having suffered through six of them with ulcers - before drifting down to London in a rather belated attempt to broaden their appeal. The pay was decent enough (£35 per week between them, which would be worth about £1,700 today), but he was drifting in terms of his career during this period, persevering with the pairing more out of a sense of personal loyalty than professional pride (his wife was beginning to be affected by arthritis, and he knew that she was desperate to fight on, for as long as possible, in spite of the pain she was feeling).

Solo comics, admiring the fineness of his timing, the precision of his diction and the smoothness of his demeanour, sometimes managed to 'borrow' him for sketches and stand-up routines, and did so with such success that his reputation as a straight man rapidly spread. He remained, nonetheless, insistent that he did not consider himself a comedian and, although the 'serious' roles that he craved were proving few and far between, he was adamant that he was not interested in serving as anyone's stooge.

This resistance would start to be seriously challenged, however, in 1942, when the agent and theatre manager Len Barry got in touch. 'One evening,' Desmonde would later reminisce, 'somebody - not my agent - came round to see me and asked if I would like to work with a comedian. They wouldn't tell me who it was that I was going to work with. They simply asked...and I simply refused.'

Barry, however, proved persistent, and, after a few days of making himself a nuisance, he persuaded Desmonde to agree to sign up for a twelve-week try-out, even though, much to his irritation, the agent still hadn't revealed the identity of his mystery comedian. 'What's he like?' asked Desmonde, trying to squeeze the details out of him. 'Oh,' said Barry confidently, 'he's a GREAT comedian.'

Desmonde would have to wait until the first day of rehearsals to discover that the comedian in question was Sid Field. Field would indeed go on to prove himself a great comedian - probably the best in Britain during his prime - but at that stage he remained something of a secret within metropolitan show business circles, having been limited by his previous manager to years of touring the provincial circuit. Now finally free of such servitude, and set up for a new show that would bring him belatedly to the nation's top tier of theatres, he was ready to elevate his act to another level with the addition of Desmonde as his straight man.

The problem was that Desmonde was far from impressed. He had never set eyes on the man before meeting him in rooms in London's Lisle Street, and he was distinctly underwhelmed to finally find out who his partner was going to be. The name was familiar - he had known of him, and the odd detail about his career - but there was no sense on Desmonde's part that he was now in the presence of a 'great' comedian.

There had certainly been no encouragement from the script he had been studying, which had struck him as minimalist to the point of seeming amateurish - 'From the scripts you got nothing,' he would say. 'Nothing at all' - and there was no improvement once they started rehearsing, because Field, before he was ready to perform in front of an audience, concentrated on learning the basic lines and blocking out the action.

It was only once they opened the show in a theatre, with a sketch about Sid trying to learn how to play golf from Desmonde's increasingly exasperated instructor, that the straight man finally realised how good his new partner had the potential to be.

The lines themselves remained only mildly amusing (JERRY: 'Put the ball down. That's right. Now make the tee.' SID: 'Make the what?' JERRY: 'Make the tee.' SID: 'I thought we were gonna play golf?'), but Field had such a rare comic intelligence, and such impish charm, that, as he reacted to the audience laughter and improvised as he went, Desmonde could only watch in wonder at what was unfolding in front of his eyes.

His only problem was that he was not sure what, of any real value, he was contributing to the comic experience. It did not help that Field, once they had finished that first performance, proved so frustratingly reticent, merely saying to him vaguely, 'Well...now you know it'.

The comedian was not intentionally seeking to unnerve his new partner - as a self-absorbed and quite nervous solo performer, he was simply not used to supplying and receiving the frankness, along with the mutual encouragement, that any good double act requires in order to thrive - but he certainly rattled him badly enough to almost lose him after sharing just one session together on stage. 'Chum,' Desmonde would recall thinking and seething about Field, 'you can go and jump. I've got a good act, I don't need you.'

The relationship, such as it was, remained - much to the straight man's mounting sense of insecurity and frustration - strangely cool and business-like throughout the three-month tour. 'I used to go into his dressing room at the beginning of the evening's show, when he was making up,' Desmonde would say, 'and he'd look up and produce a bit of small talk. But I got the feeling - "This man doesn't like me".'

When the show reached Field's native Birmingham, he gave Desmonde some local references to ingratiate himself with the audience, and the comedian, who was given a warm homecoming for a beloved son, was inspired to reach new heights of comic grace and ingenuity. Afterwards, thrilled by how well they had interacted ('Now we're getting somewhere as a team,' he thought to himself), Desmonde went to Field's dressing room intending to celebrate, only to find his partner so engrossed in conversation with an assortment of old school friends that he was made to feel not so much unwelcome as completely invisible.

'Who were all those fellows?' he later asked. 'Oh, they wouldn't interest you, son,' answered Field, 'they aren't in show business. Just friends of mine I've known for a long time.' Now utterly deflated as well as hurt by what he took as a slight, Desmonde reflected to himself sadly: 'We're back where we were'.

Feeling as though they would never really gel as a pair, he wrote that week to his agent, asking to be freed from the remaining engagements. 'I simply don't want to know about comics,' he said. 'I'm sick of them. In fact, I want to leave this weekend.'

His agent protested that he couldn't just leave in the middle of a tour. 'I can leave this weekend if I want to,' Desmonde insisted. 'It makes not a damn of difference to anybody. It couldn't matter less to Sid Field whether I leave or whether I stay. He seems to get along on his own.'

His agent, nonetheless, remained firm, and Desmonde, reluctantly, remained on the tour. Field's apparent aloofness, however, continued to niggle away at him. 'I could never find out what was going on in his mind,' he would complain. 'He would never say much. In fact, he was rather a morose man at times. It used to perplex me because I'm sociable and a poor hand at bottling things up.'

It got better on the stage, because they started to understand not just what each other was doing, but also how they were trying to do it. Jerry's job was about the syntax of a sketch, Sid's was about its spirit; Jerry had to look after the lines and control the structure, while Sid played between the words and searched out the laughs; Jerry was there to embody the idea of order and normality, Sid to symbolise anarchy and abnormality.

It barely got any better off stage, however, because there was still so little interaction between them. 'For one thing,' Desmonde would reflect, 'there had been too many backslappers around Sidney for me to get to know him really well in the short time we'd worked together, and, secondly, my old RAF ulcers were then so persistent that I could drink only very little, which didn't help me to be good company for him.'

A few weeks later, however, Field surprised him by asking suddenly if he would like to join him in a pantomime - Robinson Crusoe at Nottingham - at the end of the year. Desmonde, more out of curiosity than keenness, agreed.

It would turn out to be a big break for both of them. The London-based impresario George Black saw Field there and signed him up for a new West End revue called Strike A New Note. Field agreed on condition that Desmonde came with him.

That vote of confidence would lead to them finally feeling like a team. They knew now that they needed each other if this was going to work, and they trusted each other to make it work really well.

It was still a terrifying first night for Field, who, with a mouth bone-dry and a body already drenched in sweat, had to be physically pushed on to the stage at the start of the show, but, as Desmonde calmed him down and coaxed him back to his best, the act had never seemed so artful.

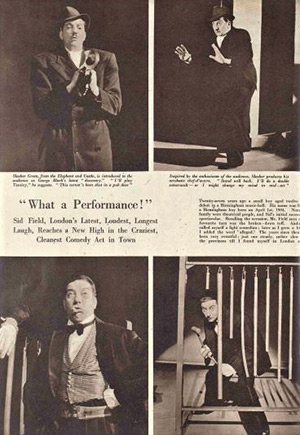

Sid appeared as the Cockney chancer Slasher Green, and Jerry as the sceptical judge of his audition; Sid then re-emerged as a muddling music professor dealing with the glockenspiel and the 'tubercular bells', while Jerry slipped off to heckle him from the audience; he then returned as a cocky American lieutenant being hammered into shape by Jerry's colonel; and then they were back as the novice golfer and increasingly irate instructor.

The audience loved them. The laughter and applause grew louder and longer with each new appearance. It was the kind of triumph that only seemed to exist in fiction, and yet here it was, happening in fact. The two men took their final bows to a standing ovation.

'Even when the show was over, I couldn't tell exactly how Sid felt,' Desmonde would later say, 'but we found ourselves alone for a moment in the dressing room and I couldn't hold back. I took hold of him as if he were my brother and I must have had tears in my eyes. All I could say was: "It's wonderful...so wonderful". Sid had run out of words, too, but, at last, we had become a real partnership.'

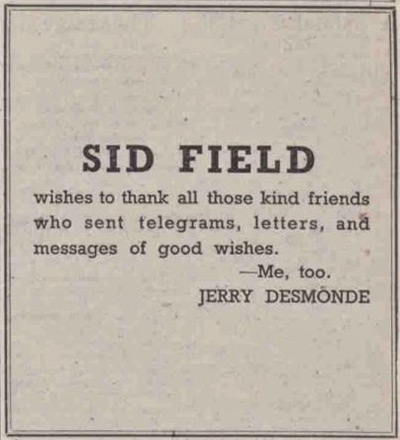

Field, of course, got the vast majority of the press attention, while Desmonde had to content himself with the odd commendation for being a 'congenial confederate' who 'ably assists and interrupts', but most of the critics appreciated the quality of his contribution (with one of them, who dubbed him 'The Prince of Feeds', marvelling at the 'almost elastic way' that the straight man kept moving to match the funny man with a range of characterisations that, in their own understated way, were as distinctive as the succession of drolls that his partner portrayed). The collaboration was admired most avidly of all by their fellow professionals, who savoured the subtlety of its comic effects.

'The great thing about them,' Eric Sykes (who saw them often) would tell me, 'was that they made you care about them - both of them. Sid, you wanted to protect, you wanted to see him enjoy himself, while Jerry, you completely understood his frustration. So you weren't just watching a funny act; you were watching two believable funny people. And that took the whole thing up to another level entirely.'

It was, indeed, a key part of their appeal. Playing to a wartime audience (rather like a lockdown audience) constantly torn within themselves between dutiful rule-followers and deeply frustrated free spirits, the Field and Desmonde relationship was not one of hero and anti-hero, good guy and bad guy, but of me and me, and you and you. They were both so vivid, both so true, that the audience bounced back and forth, sympathising with each as they laughed at the pair of them, and laughed at themselves and their neighbours.

Dominating the rest of the decade, the nation's favourite comic partnership was back in the West End in 1943 for the follow-up show, Strike It Again, and then again for another revue, Piccadilly Hayride (alongside Terry-Thomas) in 1946. They also reprised some of their most popular sketches for the movie London Town (1946), and the Cromwellian comedy The Cardboard Cavalier (1949).

One of the sketches that best captured the brilliance of both of them was a gloriously camp vignette in which Field played Sidney, an over-excited would-be society photographer, and Desmonde appeared as Whittaker, his old friend and now rather vain subject who has just been elected mayor. What was so delightfully impressive and special about this routine was that they transcended the conventional 'comic/straight man' equation and simply interacted as two charmingly funny characters:

SIDNEY: Do you know, Whittaker, really, I've never been the same since my last operation.

WHITTAKER: Oh, you poor soul. Was it serious?

SIDNEY: Serious? I should think it was!

WHITTAKER: Mmmm?

SIDNEY:: Fourteen weeks on me back with me leg up.

WHITTAKER: Ooh, really? That's dreadful! Were you stitched?

SIDNEY: Well, I certainly wasn't crocheted!

Their ongoing collaboration was only interrupted when Field, tempted into testing himself in a more conventional acting role, himself went 'straight' at the start of 1949 in Harvey - a play about an inebriated man and his relationship with an invisible six-foot three-and-one-half inch rabbit. There was no suitable part in the production for Desmonde, who must have felt somewhat disoriented watching 'his' space beside Field being filled by an imaginary animal, but they still had many new projects planned together (especially on television, where, Field predicted: 'We'll make a fortune, son').

None of them would ever happen, however, because Sid Field, after suffering a succession of heart attacks, died on 3rd February 1950, at the age of just forty-five. 'He was a supreme laughter-maker,' a devastated Desmonde said at the memorial service for his old friend. 'We shall remember him for his qualities as a man and as the greatest comedian of our time.'

Desmonde had not just lost a partner; he had also lost a living. A popular comic could still get bookings (at least for a while) without their regular straight man, but a straight man, no matter how much he might be admired, could not get engaged without a comic. At the age of forty-two, after several years racing from one success to the next, Desmonde suddenly found himself stranded.

Bob Hope would hire him whenever he was in London, but that was never very often, and several other American stars would do the same during their own fleeting visits to Britain. He was still being spoken about with great respect within show business, but, much to his frustration, that approbation was not translating into any long-term engagements.

He worked for a while with Nat Jackley - one of Field's old understudies - during the second half of 1950, and with Jimmy Wheeler a couple of years later, served as straight man to several other comics for the 1952 Royal Variety Performance, and, from early in 1953, appeared a few times on television alongside Arthur Askey. The problem was, however, that while plenty of comedians wanted to work with him, they were not so keen on sharing too much of the money with him, so they preferred to 'borrow' him briefly (and pay him cheaply) rather than formalise any arrangement.

Desmonde did manage to win a few roles in plays as a character actor, and even starred in the 1953 movie Alf's Baby, but it took three years after Field's death before he established another 'proper' comic partnership. This was when he teamed up with Norman Wisdom.

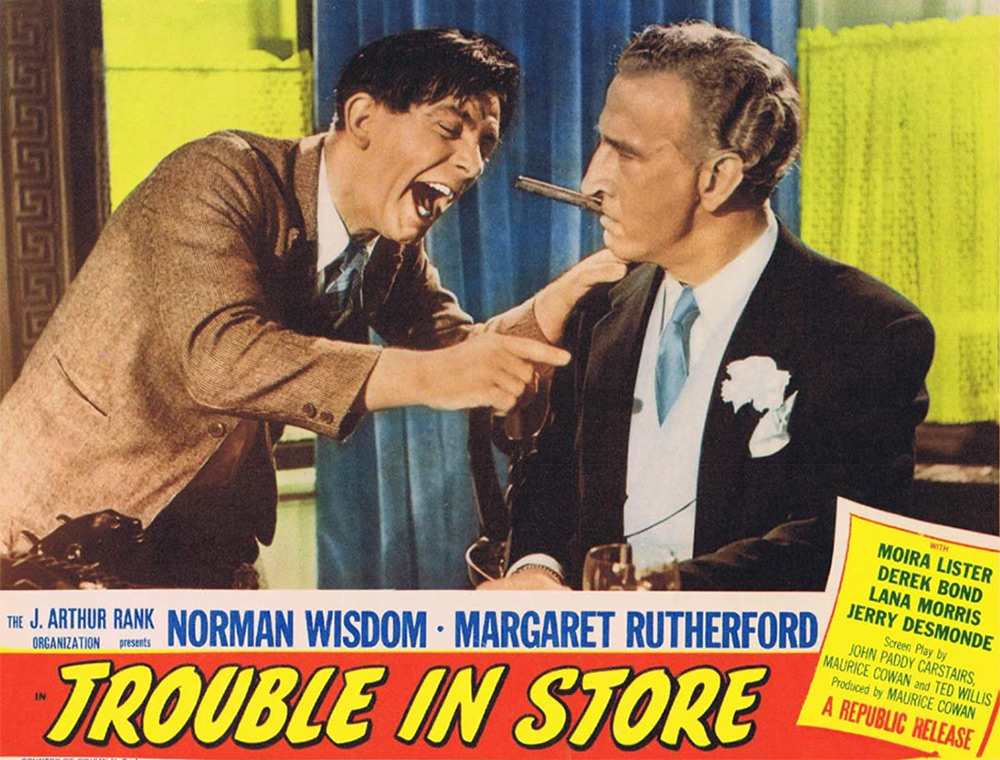

They had first worked together back at the end of 1951, on a very chaotic live broadcast called Television's Christmas Party, but it was in the summer of 1953 that they were reunited for Wisdom's debut movie as a star, Trouble In Store.

The comedian played 'Norman', a humble would-be window dresser, while Desmonde played Augustus Freeman, the ambitious new manager of Burridge's department store, and, right from the start, they worked together extremely well. In the first scene that they shared, with Freeman eager to play the paternalistic patron and Norman thinking the pair of them are just having a lark in the absent boss's office, Desmonde keeps providing the perfect counterpoint - sometimes with just a reaction, sometimes with a line, and sometimes with a sliver of slapstick - to each one of Wisdom's antics, never for a second striking a false note.

They would only actually have eight scenes together, some of them just seconds in duration and all of them together totalling a mere twenty-one minutes in a movie that lasted eighty-five minutes, but they still served as the spine of the comedy.

Desmonde's contribution was crucial for lifting the quality of the production. Whereas most of the country's straight men of the time would have laboured through their scenes via a succession of pop-eyed 'Doh!' expressions and painfully sign-posted double-takes, Desmonde (even when his face was covered with cream or custard) stayed firmly within the bounds of comic realism. The consequence was that Wisdom (who otherwise had a habit of bouncing back and forth between pathos and bathos) now had a much more 'natural' environment in which to exist, and a stronger power to push against, interacting with an authentic character rather than a mere cartoon.

Theirs would go on to be a relationship that, while never matching the standards of subtlety and sophistication that Desmonde had reached previously with Sid Field, would still be one of the most firm, familiar and effective in British cinema for the next decade or so.

Playing a very proper Foreign Office official - and craftily enacting a tea-serving skit in the style of Field's old golf sketch - in Man Of The Moment (1955); the fierce estate manager Major Willoughby in Up In The World (1956); the crooked crooner Vernon Carew in Follow A Star (1959); pompous hospital administrator Sir Hector Hardcastle in A Stitch In Time (1963); and milk managing director Walter Hunter in The Early Bird (1965) - a well as numerous other roles in plays, revues and television appearances - Desmonde was always distinctive and understated, and always ensured that Wisdom was supported with the sharpest skills that any straight man could deliver.

One critic summed up his significance well when commenting on a show that they shared at the London Palladium in 1955. Describing Desmonde as Wisdom's 'great advantage', he went on to remark:

This actor, called a 'stooge' or 'feed' in the profession, is the greatest ambassador a comic ever enjoyed. He is suave, handsome and utterly at home. A prank may shake him, but we are confident that he can never really be out of countenance. Some men are designed by nature to have well-creased trousers and to underline with one eyebrow the absurdities of lesser beings. Without his aid Mr Wisdom would be as indifferent as his detractors find him: with it he can make superior criticism fatuous, because Mr Desmonde with infinite grace has implied it anyway.

Desmonde also managed, during the same period, to shine alongside Charlie Chaplin in A King In New York (1957), as well as seeming equally at home when teaming up again with Arthur Askey in Ramsbottom Rides Again (1956).

Regardless of whether the comedy was high or low, and the scripts strong or weak, the performance was always one of the soundest on show. His entry in Who's Who in Variety listed his special talents as 'foil, stooge, feed and straight man', and he was indeed all of those things rolled into one, but he was also a very good character actor.

What he never was, unfortunately, was wealthy. Thanks to the unfortunate combination of the modest sums he was receiving as a straight man (in comparison to the comics he served with such distinction), and the mounting expenses involved in looking after his ailing wife, Jerry Desmonde was increasingly obliged to hide the fact (for the sake of pride as well as publicity) that he was often struggling to make ends meet.

His many appearances on the stage and screen might have given many the impression that the money was pouring in from all directions, but the harsh reality was that more than a few of his roles - although memorable - only required a short amount of time on the set, and the relatively small size of his payments reflected that fact. It was mainly for this reason that, in his later years, he became increasingly reliant on a second career as a TV personality to keep him and his family financially afloat.

It began in 1951, when he became one of the first regular panellists on the British version of What's My Line?. With only the one BBC channel available at that time, it meant that Desmonde was watched by huge audiences each week, and thus was established quickly as one of the medium's most recognised figures.

Thanks to viewers' enthusiastic reactions to his elegant appearance and mixture of urbanity and authority in front of the camera, he also became (once commercial television started in the middle of the decade) one of the pioneering, and most popular, quiz show hosts of the era. 'The immediate reaction to my appearance as quizmaster was pretty caustic,' he would later recall of his initial effort on ATV's Hit The Limit early in 1956. 'Some press critics named me "The Hanging Judge"; others "A character out of Dragnet". But when we started the programme it was determined that I should treat it seriously. It was not thought wise to have a gag-cracking, bubbling-over quizmaster. All I will say is that I could have been a great deal more serious. I can be positively funereal, if need be!'

Within a couple of months of this, he was also made the star of ATV's much bigger US import, The $64,000 Question, and, for the next few years, he was, if anything, better and more widely appreciated for his hosting skills than he was for those of a straight man. It never really bothered him; he was as practical as he was modest, and was grateful for the regular engagements.

The lucrative quiz master career came to an abrupt halt in 1957 when, after apparently offering his opinion once too often to the production team, ATV's boss Val Parnell stepped in and shoved him out. Some of the shock that came with this abrupt expulsion would never completely leave Desmonde (who spoke openly about how unfair he felt his firing had been), and, as several of those in the industry who had formerly embraced him now seemed to shun him, he became convinced - without, it has to be said, any concrete proof - that Parnell, one of the most powerful people in show business, had branded him 'difficult' and effectively 'blacklisted' him from television.

That conspiracy theory would be somewhat compromised by the fact that Desmonde was actually employed by ATV again, in one edition of a variety show in 1960 and in several episodes of the nostalgic Bud Flanagan vehicle Bud in 1963, as well as, very briefly, by a couple of other companies. He remained adamant, nonetheless, that his time as a TV star had been shattered by a vengeful Val Parnell.

Although he continued to find cabaret and club work during the first half of the 1960s, it was nowhere near as frequent as before. Even if any blacklist had not actually happened, younger personalities were now taking over the best positions on television, while his opportunities in British cinema - aside from his continuing association with Norman Wisdom - were being limited increasingly to such toe-curlingly cheap and cheerless enterprises as the downright bizarre comedy/sci-fi/musical Gonks Go Beat (1965). There were even some months when, swallowing his pride, he worked for a mini cab company just to earn some extra cash.

The fickleness of the business proved hard for him, at this stage in life, to take. Worn down by worry about his wife's deteriorating condition, and angered and embittered by what he regarded as various slights and snubs from former employers in commercial television ('When one door closes,' he complained, 'they all close'), he was withdrawing more and more into himself.

On 30th November 1966, after six months spent in and out of hospital, his beloved Peggy, to whom he had been married for thirty-six years, died. Jerry was left heartbroken, and without any real energy, or desire, to struggle on. 'Well, that's it,' he told one reporter. 'The one blow I can't laugh off.'

Although he still had the odd good day (one newspaper of the time carried a picture of him, looking as dapper as ever, smiling broadly as he strummed one of his vintage ukuleles) and was always prepared to perform (most recently on 6th February 1967 in a BBC Two show called Before The Fringe), he remained, as his family would later admit, 'much more depressed than average'. Unless the red light signalling a recording came on, it was often as if, his colleagues reflected, he was no longer really there.

His old friend and fellow actor Hubert Gregg met him by chance a few days into February at a small London club. He told Gregg how lonely he had been, but claimed that, although he was still sleeping badly, he had 'pulled out of all that' and was now looking forward to starting a new job as entertainments organiser for a big shipping concern.

Delighted to be reunited, they decided to move on and have supper in Gregg's apartment ('Mine is so empty,' Desmonde admitted). Gregg cooked them a pizza, very badly, and they laughed at what a disaster it was as they sat back, drank some wine and reminisced about the old days. 'Wonderful evening,' he said at the end as he was putting on his coat. 'So glad we got together.'

Gregg invited him to come back again the following week. 'It's a date,' said Desmonde firmly while shaking his hand and flashing a smile, and he wrote it straight down in his diary.

How true this good mood had been is open to question, but, if it had indeed been real, it would not last more than a day or so longer. The creeping gloom, like a winter fog, was forever threatening to envelop him once again.

Early on the morning of Friday, 10th February 1967, a little over two months after losing Peggy, he picked up his regular prescription for thirty sleeping tablets and returned to the flat at Eamont Court in St John's Wood that he was now sharing occasionally with his son, Gerald Sadler, a BBC studio manager. While Gerald prepared to leave for work, Jerry set off again, as he often did, for a solitary stroll in nearby Regent's Park.

When Gerald returned that evening, he saw that the light was on in his father's bedroom, so he turned it off and went to relax in the lounge. It was there, on a table, that he found a note. Rushing back into the bedroom, he discovered that his father was dead. He was fifty-eight years old.

Confirming a verdict of suicide, the coroner would later say that Jerry Desmonde had 'self-administered' a 'dangerous' mixture of alcohol and barbiturates. The note he left, it was added, had 'clearly indicated' his intention 'of taking his own life'.

There were a number of warm and fitting tributes recorded in the nation's newspapers ('The best of his kind we have known,' said one; 'a professional from his handsome, uncommercial head to his dancing feet', remarked another), and several more in the media over in America (where his technical expertise had always been acknowledged and appreciated even more so than at home), but, in the year or so that followed, what remained of the posthumous fame began to fade. It would not be long, indeed, before he was reduced, for many, to the status of those who seem vaguely familiar but are rarely still known by their name.

Jerry Desmonde does not deserve such a fate. He not only gave us some of the best supporting characterisations in a succession of much-loved comic productions, and pushed several of his peers to their peak while he was doing so, but he also bequeathed to younger generations of performers the finest guide to the art of making a comedian look good and get laughs.

He might have scowled, sneered and shouted on the screen, but he deserves a smile from us in return. If a definition of a straight man is ever required, the entry should simply read: 'See Jerry Desmonde'.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more