Taking it to the hilt: Jack Hylton and British comedy

Here is the first article, in what will become an occasional series within Comedy Chronicles, in which Graham McCann looks at the main impresarios involved in comedy over the past century.

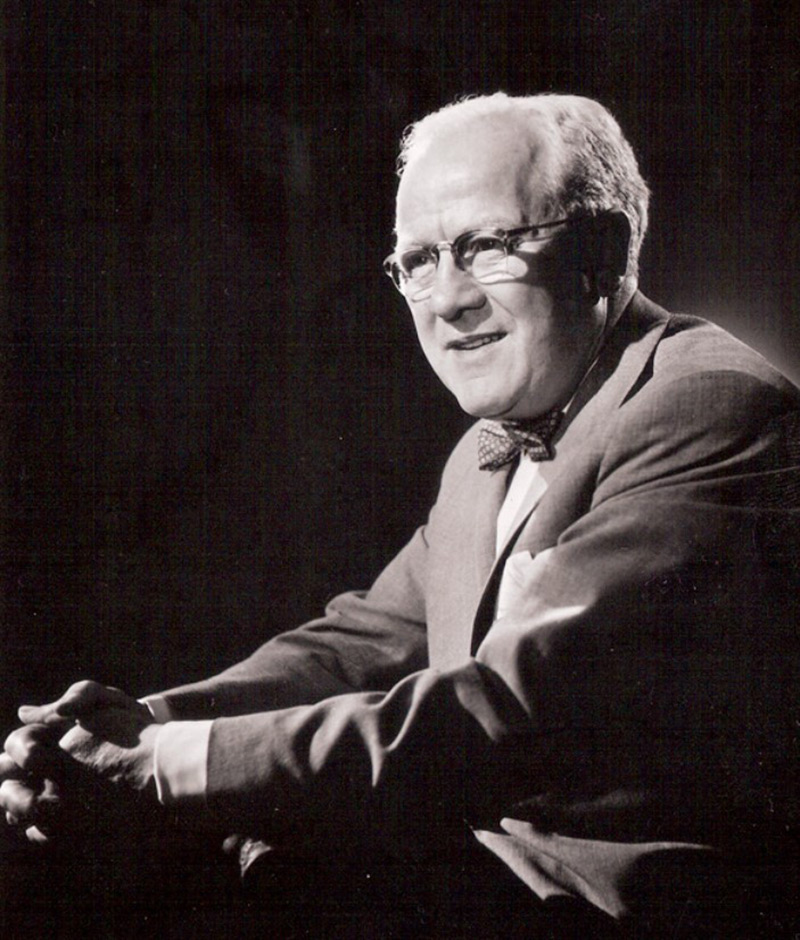

Jack Hylton must rate as one of, if not the, most extraordinary and influential impresarios in the history of British entertainment. He was a musician, composer, arranger, band leader, agent, manager, theatre owner, director of British Lion Films, director of Decca Records, one of the founders of Independent Television, a major theatrical and TV producer and a highly significant spotter and shaper of talent.

Born on 2nd July 1892 in the village of Great Lever, on the outskirts of Bolton, Lancashire, as the son of a mill worker, he spent the early years of his long career in music, where he scored a string of firsts, including, in 1921, becoming the first person in Britain ever to have his name printed on a record label; in 1926, the first British recording artist to sell a million records; and, in 1931, taking part in one of Britain's first live transatlantic broadcasts to the US via the NBC network. By 1940, after his first twenty years in the business, he was hailed as 'Britain's King of Jazz', while his band were widely acknowledged to be one of the biggest musical acts in the world, outselling every other show band in Europe and regularly breaking box office records at home and abroad.

He then began to concentrate on even bigger and broader projects. He became an impresario.

What actually is an impresario? One answer to this question is that an impresario is someone who can glimpse the big picture before it exists, and believes they know what and who is required to bring it into being. Another, less respectful, answer is that it is usually someone who can't write, can't act, can't sing, can't dance and can't direct, but has a large amount of cash, an even larger collection of contacts and an even larger ego.

There are impresarios, such as the famous P. T. Barnum, who always seem to spot a good idea, grab it, sell it and make a tidy profit. There are also impresarios, such as the infamous Max Bialystock in The Producers, who never seem to know why what they're doing goes wrong, or right, but they keep on doing it anyway, because they don't know what else to do. There are also a few, in any era, who seem to go through phases of being one or the other of the above.

Jack Hylton fits very firmly into the Barnum, rather than the Bialystock, bracket. Unlike most of his contemporaries, and, indeed, their successors, he did have a talent all of his own and he could perform, but, like the best of the rest, his greatest gift was as an organiser of others, a smart facilitator, a man who could make stars shine and spectacular things happen.

'Think champagne', he liked to say, 'and you'll be champagne. Think in terms of beer and a couple of quid a week, and you'll end up with nothing.' Few impresarios found and maintained such a balance between the facing facts and the force of will as Jack Hylton did.

For one thing, Hylton combined an eye for talent and a mind for mentoring that made him one of the great noticers and nurturers of up-and-coming performers. He gave Ernie Wise his first break at the age of thirteen. He then did the same for Eric Morecambe at fourteen. He brought the eccentric dancing of Max Wall to a broader audience. He also discovered or lent a helping hand to such performers as Tommy Handley, Arthur Askey, Pat Kirkwood, Dickie Henderson, Diana Dors, Tommy Trinder, Janet Brown, Julie Andrews, Sid James, Shirley Bassey, Peter O'Toole and Audrey Hepburn.

He appreciated the potential of people working in other aspects of entertainment. The producer Cameron Mackintosh, for example, started out as one of his stagehands. Bryan Michie, the broadcaster and talent scout, was another who served an apprenticeship under the showman. The writer Ted Willis spent his formative years working for him on numerous projects. Hylton also stepped in, at the end of the 1930s, to save the London Symphony Orchestra from bankruptcy and revive it for a wider audience.

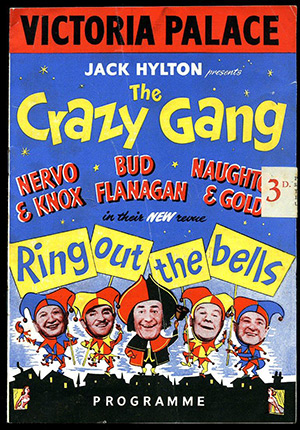

His impact on British comedy, in particular, was impressive during an era that stretched from the Thirties through to the Sixties. The Crazy Gang (comprising Bud Flanagan, Chesney Allen, Jimmy Nervo, Teddy Knox, Charlie Naughton & Jimmy Gold and Eddie Gray) benefitted from his patronage and guidance from close to the start and all the way to the end of their long collective career. He also bought the theatrical rights to the radio shows ITMA and Take It From Here and took to touring them on the stage, helped nurture the nascent career of Morecambe & Wise, made sure that the Royal Variety Performances that he organised always featured comics in prime places, and, via the fifteen London theatres he owned or controlled, brought more comedians to the public than just about any other producer in show business.

Then, in the middle of the 1950s, came his entry into television. Hylton - recently hailed as the country's 'Star Showman' by the Variety Club of Great Britain - joined one of the new commercial companies, the London weekday TV contractor Associated-Rediffusion (A-R), as its advisor on Light Entertainment in a deal that reportedly assured him £100,000 each year. He founded Jack Hylton Television Productions Ltd at the same time (14th July 1955) to produce a range of light entertainment programming exclusively for A-R.

This promised a great deal for television viewers. Hylton, after all, was a heavyweight presence, with huge experience and expertise in just about every sphere of the entertainment world, as well as a massive list of contacts and a great gift for getting things done.

What the deal actually delivered, however, would prove a disappointment. The main explanation for this was the fact that Hylton entered television at the right time but for the wrong reasons.

He was still a theatre man. He needed to become a television man.

Several of his contemporaries were jumping ship - selling up their theatres and shifting their investment, and interests, to television. Hylton was sticking with his theatres and looking to television, mainly, to help promote their productions.

Whereas many other producers were using television to look forward, therefore, Hylton was using it to look back (or at least sideways); whereas others were treating it as a medium in its own right, he was treating it more like a servant of, and showcase for, a more traditional form of entertainment. While the new trend was to try to get people to stay inside their homes glued to their sets, Hylton was still trying to lure them back out into the theatres.

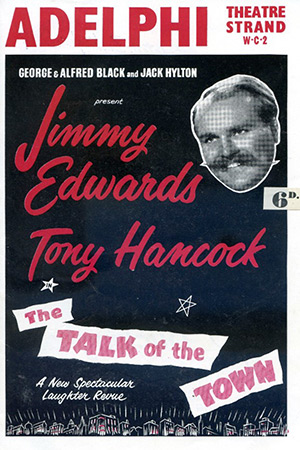

His first television show, billed as Variety (ITV, 29th September 1955), reflected this ominously restricted ambition, packed as it was with acts (including Shirley Bassey on her TV debut) and material from one of his then-current stage revues, The Talk Of The Town. There was nothing that was intrinsically wrong with it as entertainment, except that, with its unimaginative presentation, it simply did not seem so suited to television.

This would have been far easier to forgive, as a cautious first step into the small screen world, had it not been followed by a long succession of other shows that reflected a similar lack of curiosity, let alone efficiency, in exploring television as television. The cameras seemed just to be there to record whatever was happening on the stage, passively and slavishly, while the theatre shows received a plug.

Each new programme that Hylton put out (aided by Mike Sullivan, his head of bookings and another strongly theatre-oriented operator) thus seemed either to be promoting or reviving or previewing something that was, or had been, or would soon be, happening somewhere other than in the box in the corner. They were like extended commercials stuck in the spaces between the normal commercial breaks.

There was, for example, Arthur Askey and Glenn Melvyn in the sitcom Love And Kisses (ITV, 1955), which was nothing more than a stretched-out five-part reprise of the stage play of the same name, in which its stars had been touring (via Hylton-owned venues) for most of that year. Hylton had simply arranged a month prior to transmission to film one of the performances at the Prince's Theatre in London, and then cut up the recording into five equal segments. The only original element was a very brief introduction and epilogue to each week's edition, filmed specially by Askey, to keep the viewers apprised of the ongoing storyline and to cue the next show in the schedules.

Hylton then did something very similar with You'd Never Believe It (ITV, 1956), a short variety series hosted very awkwardly by the ageing stand-up comic Max Miller. Each episode came from one of Hylton's London theatres, filmed in a static manner by a trio of cameras. One angry reviewer remarked that, rather than just never believing it, he wished that he'd never seen it, either.

Many young and ambitious programme-makers, eager to push the medium and explore its full potential, were infuriated by how unadventurous Hylton's high-profile output continued to be, while a fair few senior executives were bristling at the bad publicity it was attracting to the commercial network as a whole, exposing all of them to charges of cheapness, a lack of imagination and a shameful degree of amateurism ('Mr Hylton's shows, which cost ITV a sizeable chunk of its overdraft, have produced among them a few which have reached a new low in TV light entertainment', one especially exasperated critic blasted. 'So badly-presented, so clearly under-rehearsed have some of them seemed to be, that Mr Hylton could only ask himself what the new excursion can do for his reputation').

Hylton himself, however, though privately stung by the critical assault, put on a brave face and carried on as before. He could, to be fair to him, point to the ratings in support of his policy - his shows had hit the ground running as far as helping ITV compete with the BBC was concerned, with the majority of them consistently featuring in the weekly top ten list of the most-watched programmes - and so he felt that he was doing, if anything, better than many had expected.

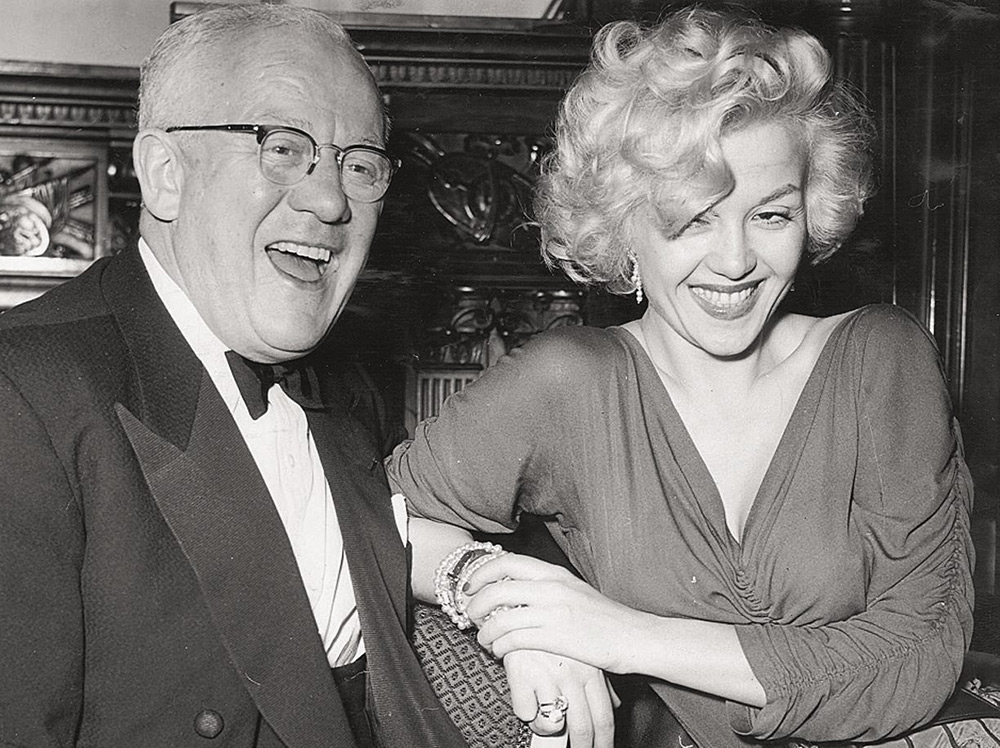

As time went on, nonetheless, even some viewers (who had been happy enough initially to see so many big-name theatre acts on the small screen for free) started to feel not only underwhelmed by the predictability of his output but also somewhat insulted by the self-indulgence it often contained. There was, for example, the almost comical Citizen Kane-style over-exposure of the notoriously priapic impresario's then-lover, the actor and would-be opera singer Rosalina Neri (hailed at the time, mainly by Hylton himself, as 'the Italian Marilyn Monroe', and kicked off Italian TV screens for sporting a neckline that was considered far too daring), who would pop up and burst into song, often without any reason, on countless Hylton productions (in addition to her own, critically mauled, series, The Rosalina Neri Show).

Other programmes that were panned included The Albany Club (which only came into being because Hylton had just bought the actual Albany Club and wanted something to do with it, and which one critic dismissed as the 'site of some of the worst ITV variety ever un-produced'; The Music Box, which was yet another ragbag of shameless plugs for his theatre projects; The Alan Young Show, which featured the eponymous Canadian actor/comedian (the future human sidekick of the talking horse Mr Ed) doing mostly the same sketches he had already performed on his US shows; Gert And Daisy, a sitcom featuring the double act of Elsie and Doris Waters but with scripts that ignored their own authentic input in favour of clichéd comic dialogue and set-ups; and the disastrous game show Make Me Laugh, which saw various contestants try to win cash by keeping a straight face while ageing members of The Crazy Gang laboured largely in vain to make them giggle (with the result that quite a large amount of cash ended up being paid out).

Then there were his regular and thoroughly formulaic variety showcases, billed (like the others) under the banner of Jack Hylton Presents, about which critics soon started to complain that, in spite of their range of crowd-pleasing headlining stars, they were far too often spoiled by 'acres of stage, unimpressive "sets" and hackneyed supporting acts'.

Then there was his much-derided policy of buying up job lots of old sitcom and sketch show scripts from American TV and lazily recycling them (with very little, if any, attempt to Anglicise the characters, situations or comedy) for 'new' British shows of his own.

There was, in short, very little that Jack Hylton did, after his first year or so in the medium, that did not elicit a critical sneer. When the man himself (an unapologetic 'champagne socialist') appeared on TV, at the start of October 1959, in a Labour Party election broadcast, one newspaper joked that 'it was the first good television programme he'd ever been associated with'.

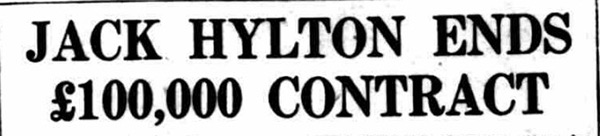

After four years of this, Associated-Rediffusion, tiring of all the bad publicity, ended its exclusive deal with Jack Hylton in November 1959. Hylton himself - ever the self-hyping impresario - would race to put a positive spin on the split, with a spokesman for him announcing: 'He has completed some very big plans for next year. They are of such magnitude that he could not possibly carry on his television programme contracting activities simultaneously.'

A-R and other ITV insiders, on the other hand, were equally quick to brief the press that they had been looking to end the relationship for some time, having grown increasingly resentful of the power he possessed, the poor judgement it was felt he had displayed and his stubborn refusal to listen to others' advice. As one report accurately but rather acidly put it, 'Hylton was highly sensitive to the severe criticism he received for his shows and in turn Associated-Rediffusion became highly sensitive to Jack Hylton'.

He continued, however, to be involved in commercial television, as a director of and significant shareholder in Television Wales and the West (TWW - the current franchise holder for those parts of the UK), and his production company was now free to make programmes for the full range of independent broadcasters both at home and abroad. The view that he was old-fashioned, nonetheless, was now widespread, and, while he and his colleagues proposed a few programme ideas, there was little interest in what was being offered.

1960 came and went without any discernible sign of the 'big plans' of such 'magnitude' that were supposed to have precipitated the split with A-R (he did help organise that year's Royal Variety Performance, but he had done so before without needing to clear the rest of his schedule), and Hylton's only major action on behalf of TWW during this period was to persuade it to invest unusually heavily in the theatre world, including the purchasing of the freehold of the Prince's Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue. After all of his years in the new medium, his eyes were still drifting back to the old one.

During his time in television, Hylton recorded some two hundred and ninety-five programmes, featuring well over nine thousand entertainers. The last Jack Hylton Presents logo appeared on 13th April 1960, following several weeks of nostalgic repeats of some of his most notable shows.

Few, in truth, seemed sad to see him and his company go. Indeed, Peter Black, one of the most prominent TV critics of the time (and Hylton's own personal bête noire), would later condemn the impresario's regime as 'one of the most abject episodes in ITV's history' because it appeared to support those who had predicted, at the start of commercial television, that too many people would 'love the lowest when they see it'.

One might be tempted, in response to such an assertion, to sound rather like the Major in Fawlty Towers when he hears the dump dismissed as the 'crummiest, shoddiest, worst-run hotel in the whole of Western Europe': 'No! No, I won't have that! There's a place in Eastbourne...' Similarly, there have been other, and rather more enduring, underwhelming elements in ITV's evolution that are arguably even more deserving of such ire.

It would definitely be unfair to encourage the impression - which has long been in circulation - that nothing positive nor interesting - at least from a comedy perspective - came from Hylton's time in television. If one actually looks at his record, it is clear that, to varying extents, he was at least a friend to funny people.

His big variety productions, for example, proved very good showcases for up-and-coming comics, among many types of performer. If you had a decent enough act, and you were getting a good reaction in the theatres or clubs, Hylton's team of talent spotters would almost certainly see you and find a spot for you on the screen.

Hylton was also undeniably active, throughout his time in TV, as a shaper of comic careers. Arthur Askey, for instance, was helped greatly by Hylton as he worked to establish himself in the medium. First in Love And Kisses (1955), then in a couple of Christmas specials, three series of Before Your Very Eyes (1956-8), one series of Living It Up (1957) and several more specials and guest spots, it was Hylton's patronage that enabled him to build up a solid and fairly lucrative second career on commercial television.

The impresario did much the same for Alfred Marks. An articulate, versatile and sophisticated comic performer, Marks is not that well-remembered these days but, thanks in part to Jack Hylton, he became one of the leading TV comedians of the Fifties.

Alfred Marks Time (1956-1961), a revue-style show which ran for five series, was arguably the first major hit comedy for commercial television, not only attracting large audiences but also a rare amount of critical praise. 'One of the brightest comedy shows on the air', claimed one reviewer, while another (lauding it for being 'well thought-out and slickly produced') declared: 'Rarely does a series of shows with one personality as a centrepiece maintain a high standard throughout, yet Alfred Marks Time [...] keeps a high standard of originality and wit'.

Featuring everything from classical musicians and opera singers to slapstick artists and circus acts, along with parodies of Shakespeare, Victorian melodrama and B-movies, it was widely admired in America as well as Britain (earning Marks some high-profile bookings in New York and LA) and certainly proved that Hylton and his team, at least on the odd occasion, could indeed get the form as well as the content right to suit a small screen audience.

There was also no doubting Hylton's ambition to repeat such a success with other comic talents. It did not quite work out with the northern stand-up comic Al Read, who was given his first chance on television in 1956 with a far more typically 'Hyltonesque' programme that consisted simply of a filmed excerpt from his current stage show (in one of Hylton's theatres) called Such Is Life, but it was still a well-meaning sign of support towards one of the country's most interesting comic personalities of the time.

It worked rather better with Tony Hancock. Hylton had a 'difficult' relationship with the star - he had him under contract for his theatre appearances, while the BBC had effective control over his radio work, and there had been several clashes between the two men (and employers) as the performer tried to juggle his various commitments. There had been a particularly bitter bust-up in 1955, when Hancock, feeling trapped in one of Hylton's long-running West End revues, had suddenly gone AWOL to Rome to recuperate, but the impresario still had plenty of respect for his ability, and was shrewd enough to continue to see the performer's burgeoning popularity as something ITV really ought to exploit.

The Tony Hancock Show (1956), therefore, was quite a sharp piece of opportunism by Hylton, as he knew the BBC was already planning to adapt his radio series for TV and his involvement with the commercial broadcaster thus represented quite a coup. Sketch-based rather than a sitcom, the somewhat hurried production (which also featured June Whitfield) was decidedly rough around the edges, and certainly far less pacy and polished than the programmes Duncan Wood would soon be overseeing for the BBC, but it still proved popular with viewers even if some of the critics complained about the uneven quality of the comedy.

There would be a second series later the same year, but, with the writing input now compromised by multiple contractual and political problems (and Hancock himself impatient to concentrate on his BBC shows), both the standard and style were less stable and strong. Once again, however, the programmes performed well enough in the ratings, and represented another fairly encouraging step for the fledgling network's move into TV comedy.

One of the highlights of Hylton's contribution to this area was his championing of Dickie Henderson. A long-standing friend of the Henderson family - he had known Dick Henderson Snr, a popular comedian and singer, since the 1920s, employed his two daughters as a musical act from the mid-1930s onwards, and first hired his son as a prop boy while he was still in school - Hylton was a genuine fan of Dickie Jnr's talent as an all-round entertainer, and saw him - quite rightly as it turned out - as one of the future fixtures of British light entertainment.

Henderson had recently enjoyed some exposure with a show over on ATV, but had clashed at times with one of the other prominent impresarios involved in commercial TV at the time, Val Parnell. Hylton thus stepped in and shaped a new star vehicle for him on A-R, The Dickie Henderson Half-Hour (1958-9). Designed to show-off the full range of his abilities as a comedian, singer, dancer and actor, it was a lively and varied affair that (although compromised to some extent by its reliance on Hylton's infamous stash of second-hand American sketch material) easily made the top ten most-watched shows on a regular basis, and succeeded in confirming its star as one of the most popular young TV personalities of the era.

Hylton managed to make a few other less immediate and more low-key comedy connections - for example, the sitcom that he produced for Glenn Melvyn, I'm Not Bothered (1956), introduced Ronnie Barker to television viewers - which, when combined with all of the other comic patronage he provided, shows that his legacy in this sense is considerably greater, and more enduring, than has often been suggested.

His attitude, indeed, seemed to grow, albeit belatedly, more modern and ambitious once his formal ties to commercial television had ended. Still remarkably lively as he entered into his seventies, Hylton shook off the recent 'where did it all go wrong' media coverage by marrying Beverley Prowse, an Australian model and former beauty queen (who, at twenty-nine, was forty-one years his junior) in 1963, bought even more properties all over the world, secured the UK rights to the hit stage musical Funny Girl, played a leading (and well-publicised) role alongside Labour leader Harold Wilson in ending the 1964 ITV technicians' strike, and started making interesting new industry connections with those who better understood the younger generation.

Then, in the summer of 1964, in a move described by one newspaper as 'the biggest surprise show business has had for years', he announced that he was setting up a major new multi-media empire - Jack Hylton and Associates - with world-wide interests in theatre, television, movies and newspapers. British filmmakers Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder, US producer Joseph Cates and Australian media mogul Sir Frank Packer were confirmed as partners, with Hylton himself installed as chairman. Long-term plans for the enterprise would end up being thwarted, however, by Hylton's sudden death, from a heart attack at the age of seventy-two, on 29th January 1965.

It was telling that his passing was marked by so many tributes of genuine affection as well as respect. As impresarios go, Jack Hylton, for all his faults, was one of the more benign of the breed.

The actor Laurence Harvey, who had recently starred in his last theatrical production, Camelot, said of him: 'He had that great quality, which all very successful people have, he had courage. He was a fighter. He was a man who never said "I can't". He always found a way to do everything.'

It was a good summation of what, and how, an impresario aims to achieve. As for Hylton's own distinctive legacy, aside from his many musical activities (which were undeniably impressive) and his time as a TV executive (which was obviously far more contentious), he merits remembering as a reliable ally of British comedy, and as a boss who, though driven like the others by dreams of wealth, power and influence, also managed never to forget his background, his affinity for performers and his deep desire to please the public.

See also:

Val Parnell profile

Lew Grade profile

Bernard Delfont

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreJack Hylton Presents

Jack Hylton, impresario and former band leader, was adviser on light entertainment to the first ITV company, Associated-Rediffusion, and formed his own independent company to make programmes for A-R. Throughout the late 1950s Jack Hylton Television Productions presented some of the greatest names in British variety theatre. The list of artists who appeared under his banner reads like a Who's Who of variety, from Tony Hancock, Arthur Askey and The Crazy Gang to Dickie Henderson, Alfred Marks and Anne Shelton.

Remarkably, over 100 of Hylton's programmes have survived and are now in the care of the National Film & Television Archive. This book tells the fascinating and sometimes surprising story of Hylton's ultimately unsuccessful foray into television. Also included are details of all the programmes held by NFTVA, along with full cast lists and credits for this exciting collection.

First published: Monday 1st April 1996

- Publisher: BFI

- Pages: 116

- Catalogue: 9780851705514

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

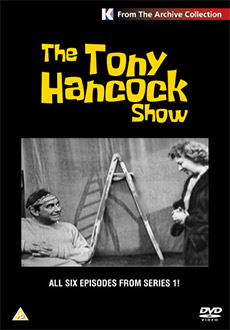

The Tony Hancock Show

Tony Hancock stars in his first ever television series.

Co-starring June Whitfield, Dick Emery, Hattie Jacques and others, this sketch show enjoys scripts by Eric Sykes and Larry Stephens.

Two series were broadcast on the ITV network in 1956 and 1957, but now only the first is known to survive, and is presented here for the very first time.

First released: Sunday 13th February 2022

- Distributor: Kaleidoscope

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Catalogue: KP1952

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Dickie Henderson On Radio And Television

A new book and 75-minute DVD collection examining and celebrating the all-too-short life and career of star entertainer, comedian and early TV favourite Dickie Henderson, a ratings-winning ITV star through the 1950s, 60s and 70s before his premature death in 1985 at the age of only 62.

Includes two episodes of the domestic sitcom The Dickie Henderson Show by Jimmy Grafton and Jeremy Lloyd, and an unbroadcast sketch/chat show pilot, I Wish I'd Said That, written by Barry Cryer and co-starring Kenneth Williams.

First published: Saturday 5th August 2023

- Publisher: Kaleidoscope

- Pages: 72

- Catalogue: 9781900203869

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.