Mr Hobbs takes a vacation: When it all backfired for Jack Hobbs

Poor Jack Hobbs. It could have happened to anyone - it has happened, in varying ways and to different degrees, to many people - but, because of the peculiarly harrowing and humiliating way that it happened to him, it is now all that people talk about, if they ever do still talk about, Jack Hobbs.

Before we get to that particular story - and please do try to be patient - we should clarify something. The Jack Hobbs we will be discussing was not the Jack Hobbs who was born in Cambridge and went on, as a cricketer for Surrey and England, to be hailed as one of the game's greatest and most prolific batsmen, scoring 61,237 first-class runs and 197 centuries and being knighted for his stellar achievements. Our Jack Hobbs is quite another, rather humbler, Jack Hobbs.

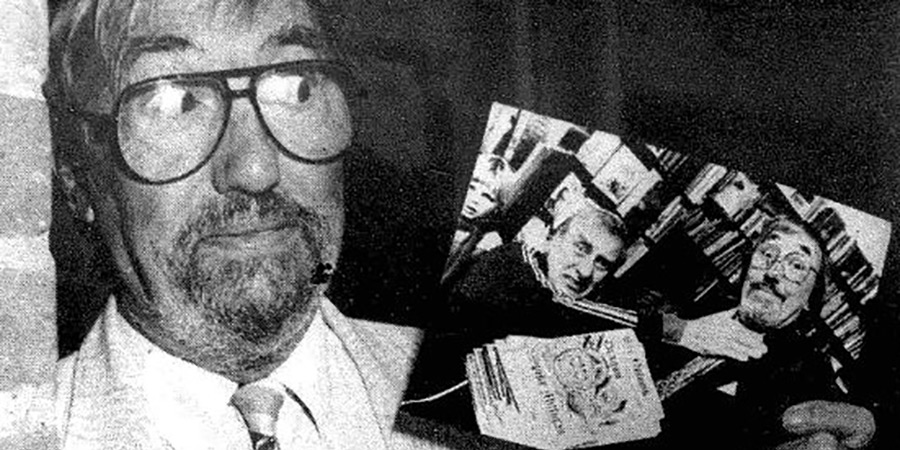

Our Jack Hobbs was a publisher. Born in Yorkshire in 1926, he had always been fascinated with books, spending hours at a time as a child ensconced in his local library, exploring all of the nearby bookshops, and building up his own collection, not only reading each volume but also speculating about the author and the whole business of putting down the words and getting the pages printed and the covers coloured.

As an adult, he would, as soon as was able, run a second-hand bookshop all of his own, half-hidden away, like a lost treasure, in a run-down part of town, but the best way to channel his passion, he later found, was as someone who brought the writer to the attention of the audience. He became a commissioning editor.

He started his publishing career, shortly after the end of the Second World War, at Hugh Evelyn Ltd at 9 Fitzroy Square in London, learning the trade as an all-purpose assistant in a small but busy office specialising in subjects relating to the fine arts, and then, when ready for a more senior role, moved on to the bigger and broader Jonathan Cape in Bedford Square, where he got to glimpse the galleys of Ian Fleming's latest James Bond novels, and then on to Michael Joseph at 26 Bloomsbury Street. It would be here at Michael Joseph that, as he rose through the ranks, he would work on a wide range of projects with a diverse collection of authors, and witness close-up the preparation for the public of everything from Richard Condon's The Manchurian Candidate to The Shell Nature Lovers' Atlas.

He co-founded, in those early days, as a kind of hobby, a very small publishing house of his own, called Scorpion Press, with his friends John Rolf and John Sankey, dealing mainly in poetry collections. It did introduce some promising work by some up-and-coming poets, such as Christopher Logue and Peter Porter, but it did not last long, lost him quite a bit of cash, and he was soon back tending full-time to the needs of the Michael Joseph list of authors.

His own most notable working relationship, however, would be with Spike Milligan. Their long and (by Spike's standards) strong friendship began in the late 1960s, when Hobbs, as a kind of sideline to his activities at Michael Joseph, was serving as a director of Private Eye Productions, a company connected to the fortnightly satirical magazine Private Eye.

His involvement had come about after he had started being a regular visitor to Peter Cook's Establishment Club in Soho. A naturally sociable character, Hobbs had met and grown friendly with Cook and his colleagues (the Private Eye editorial team had, by this time, moved into the same building), and they had started consulting him on various commercial projects they were planning.

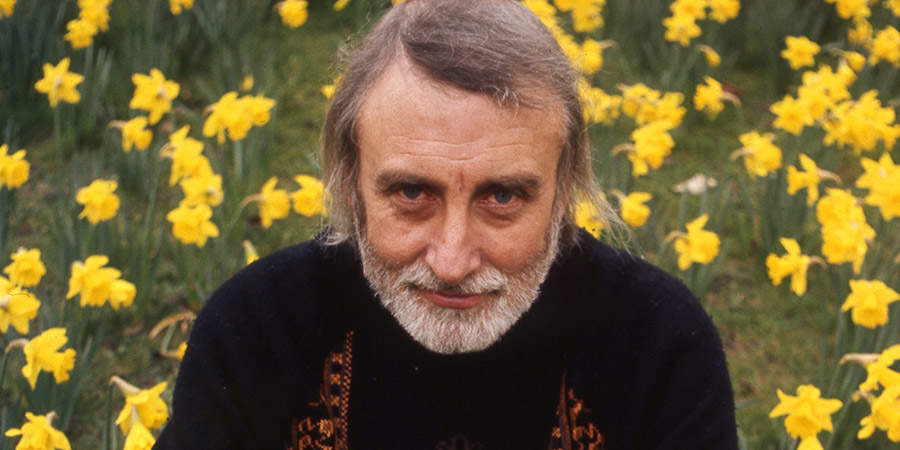

One of his fellow directors, William Rushton, happened to mention to Hobbs, over a leisurely drink one evening, that Spike Milligan had been telling his friends that he wanted to publish a 'special' kind of book and he wanted to do it 'quickly'. Hobbs - a long-time admirer of Milligan and The Goons - was intrigued.

Eager to seize this opportunity, he got in touch with the comedian early the following morning, volunteering his expertise as an experienced operator in the publishing world. Milligan, who in those days was not, was happy to accept his offer of help.

It transpired that Milligan wanted to organise a special surprise for his elderly father, Leo, who was now based in Woy Woy in Australia and was about to be celebrating his birthday. Having served as a regimental sergeant-major in the British Indian Army, Leo considered himself an authority on various types of weaponry, especially six-guns, having accumulated a large collection in his house, and had written extensively on the subject over the course of many years in specialist arms journals and magazines.

Spike told Hobbs how he wanted now to collect these articles together, publish them in book form and present the first copy to his father - within a time frame of seven weeks. He already had a trip Down Under planned, he explained, and the idea of this touching gesture from a son to a father had only recently occurred to him, so the whole process would have to be completed as soon as possible.

Hobbs, seeing that Milligan was genuinely serious about the plan (he had a vision of his father, upon opening the unexpected package, breaking down in tears, sobbing, 'What a wonderful son!'), agreed to take on the challenge. He flew off straight to Glasgow, where he knew there was a publisher, Thomas Nelson & Sons, that was unusually flexible, quick and cost-effective when it came to unusual projects, and, calling in a favour, negotiated a deal that would see them produce just three copies of the book, each bound in green Morocco leather - one for Spike, one for his father and one for Spike's younger brother Desmond.

Keen to impress, Hobbs oversaw the whole process with exceptional care, checking the galleys and correcting the proofs, and managed, with a few days to spare, to meet the tight deadline. The copies were then hurriedly airfreighted over to Australia, just in time for Spike's arrival and his father's birthday party.

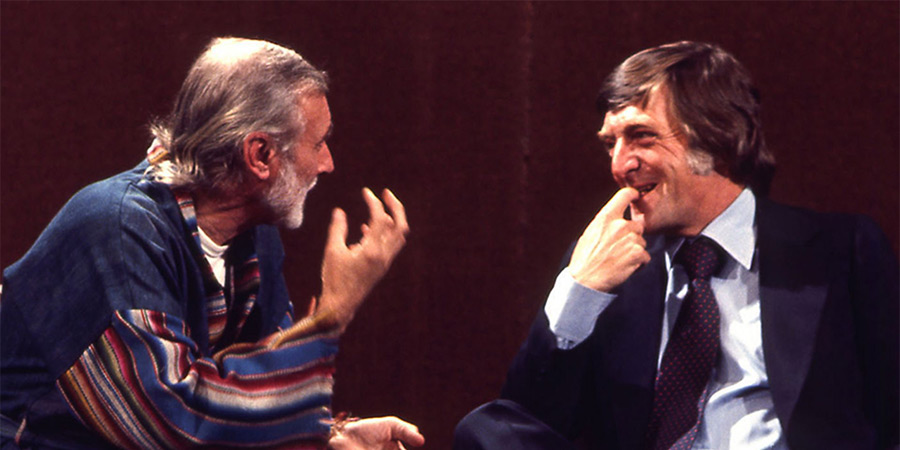

Spike, thrilled that everything had gone exactly as planned, felt deeply in Hobbs' debt. Once he was back in Britain, he had a celebratory dinner with his new friend (who was eight years his junior), and, as they relaxed in each other's company, they found that they shared many interests, including a passion for jazz (Spike played the trumpet and guitar, Jack the piano) as well as a love of writing and comedy along with a complicated attitude to their respective experiences of military service during the war.

They complemented each other well. Jack, knowing that Spike (having grown increasingly frustrated by his treatment by radio and television producers) had ambitions to branch out into books, was willing and able to serve as his editor, while Spike, appreciating Jack's fascination with humour, was happy to act as his celebrity advisor. The more that they met and chatted, the closer they grew, and it was not long before Hobbs had convinced Milligan that it was a good time to start work on his wartime memoirs.

Hobbs, in his position at Michael Joseph, arranged for the project to be commissioned, and the finished product, Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall, would, after several years of false-starts and struggles, be published in 1971. Warmly praised by most critics both at home and abroad, and hugely and enduringly successful commercially, it gave Milligan a new lease of life at a time when, after watching with envy as the Monty Python troupe took over and extended much of his old TV audience, he had been fearing that his career was well on the decline, and knew that Hobbs had, in large part, been responsible for steering him in this new and satisfying direction.

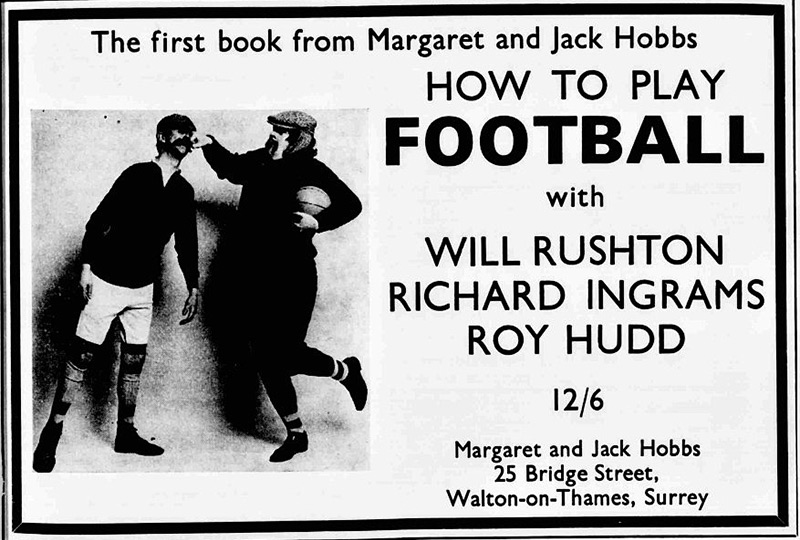

Hobbs, by this time, had become a publisher in his own right. At the end of 1968 he had launched (with his wife) his own small and independent publishing house called Margaret and Jack Hobbs - usually abbreviated to M & J Hobbs - based in offices near their home at Walton-on-Thames, and Spike was one of the first authors to sign up.

Later expanding their enterprise by establishing an international distribution arrangement with his old company of Michael Joseph, Hobbs would go on to collect and commission a large number of writers specialising in humour (including Eric Sykes, William Rushton, Richard Ingrams, Barry Fantoni, Ronnie Corbett, Cardew Robinson, Harry Secombe, Johnny Speight, Dudley Moore, Roy Hudd and John Antrobus).

It would be the output by Milligan, however, that would be the jewel in the company's crown. Under Hobbs' guidance, a veritable library of Spike's writing, encompassing everything from substantial works to scribbled whimsies and bottom-drawer dregs, was duly put in motion, with titles that would include, aside from his Goon-related collections, The Bedside Milligan (1969); Milligan's Ark (1971); "Rommel?" "Gunner Who?" (1974); Monty: His Part in My Victory (1976); The Spike Milligan Letters (1977); Mussolini: His Part in My Downfall (1978); Open Heart University (1979); Unspun socks from a chicken's laundry (1981); More Spike Milligan Letters (1984); Goodbye Soldier (1986); It ends with magic: a Milligan family story (1990); and Peace Work (1991).

Milligan would hail Hobbs in one of these books as a 'friend, pianist and fellow manic depressive', and there can be no real doubt as to the importance of Jack's role in ensuring that Spike persevered with his publishing career throughout the next few decades. He acted, in effect, as the link, the hyphen, the buckle, that kept Milligan connected (whether he wanted to be or not) to the outside world.

One of their contemporaries at Michael Joseph would later confirm that Jack, unlike most conventional in-house editors, had the time, patience and personality required to 'jolly Spike along' and ensure (in spite of those days or weeks when depression drove the writer to break down and lock himself away inside his office) that each project was completed, while one of their mutual friends, the director Joe McGrath, agreed that Jack's rare ability to act as a good audience and reliable amanuensis as well as an authoritative editor was crucial in getting the best out of such a vulnerable and volatile character.

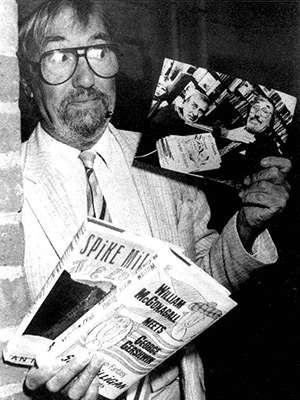

They interacted so well that, on some occasions, they even blended their roles together by collaborating as co-authors on the (decidedly) odd book. Their shared desire, for example, to celebrate the heroic awfulness of William McGonagall, the unshakeably deluded Scot widely regarded as the worst poet in the world (one of his efforts went as follows: 'The chicken is a noble beast / The cow is more forlorner / Standing in the pouring rain / With a leg at every corner'), evolved over the years from co-hosting an annual commemorative dinner (attended by Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe, Peter Cook and various other lovers of the comically absurd) to countless pastiches, a number of charity readings and the drafting of a script for a possible play or movie.

Eventually the pair got together and, fuelled by toasted cheese sandwiches and pots of tea, started co-writing what would end up as a quartet of books on the subject: The Great McGonagall Scrapbook (1975); William McGonagall: The Truth at Last (1976); William McGonagall Meets George Gershwin: A Scottish Fantasy (1988); and William McGonagall: Freefall (1992). They would also team up for several other unrelated projects, including The Milligan Book of Records (1975).

Later on, Hobbs would also encourage Spike's long-serving and long-suffering agent and manager, Norma Farnes, to start writing her own memoir (eventually published in 2003), and he was instrumental in urging and advising her as to how best to open up and share with the public the Milligan and Goon archives. Even after his death, she would still refer to 'Our Jack' when she was mulling over the next move for Milligan and all of his memorabilia.

It is at least in part down to Jack Hobbs, therefore, that there is still so much to remind us of Spike Milligan. It is largely down to Spike Milligan, however, that there is still mainly just one thing to remind us of Jack Hobbs.

This brings us, at last, to the harrowing, the horrible but hard-not-to-laugh-at, thing that happened to Jack Hobbs, and the awful mistake he later made in confiding about what had happened to his dear old friend Spike. They were having one of their enjoyable 'off-duty' days together, sharing a meal and drinking some wine and making each other laugh, when Jack, now addicted to the mutual one-upmanship of their anecdotage, decided to share with Spike a story about a holiday he had taken - and its aftermath - a few years after the end of the war.

It had been his time in military service, moving from one part of the world to another, that had kindled in Hobbs a keen sense of wanderlust. He would, once peace returned, take every opportunity he could to travel widely abroad and explore other countries and cultures.

One of these vacations saw him spend a couple of weeks in and around the coastal city of Paphos in southwest Cyprus. It was all going very well - as usual, he took in all the sights, went wine-tasting, shopped at the bustling local markets, walked in the mountains, swam in the Blue Lagoon, sat out in the sun and tried as many of the local delicacies as possible.

The latter activity, however, was where, this time, things went wrong. He would be unsure what dish did it, but, towards the end of the holiday, he was struck down with a spectacularly explosive bout of dysentery.

Pale, drained and dehydrated, and pumped full with medication, he managed to fly back to England for the end of the weekend, where he spent his remaining few hours of freedom rushing back and forth between the bedroom and the bathroom. When Monday morning arrived, dragging himself out onto the train and into London to resume work at Michael Joseph's, he groaned while his stomach gurgled throughout the next few hours, making several frantic dashes to the lavatory, until, by early in the afternoon, he could stand it, or sit it, no more.

He asked his boss if he could go home early. His boss, who - like everyone else in the office - had been viewing him, like a bomb that could go off at any moment, with some alarm for much of the day - eagerly granted him his request, and Hobbs, much to everyone else's relief as well as his own, hurried out of the building.

His home was in Walton-on-Thames, so he needed to get across London before the rush hour started and catch a train at Waterloo Station. Afraid, in his delicate state, to try a taxi or the Tube, he started walking there, perspiring greatly, grimacing every now and then from stomach cramps as his insides continued to gurgle ominously and audibly.

He had walked about two-thirds of the way to his destination, gradually moving a little more steadily, breathing a little more easily, and was thus finally starting to feel slightly more confident that he was going to get through this ordeal without any further incident. Then disaster struck.

He coughed.

He stopped still on the pavement, as his eyebrows shot up and his mouth dropped open, as if ambushed by his own body. The damage, he realised, was done.

Now he was, quite literally, in a real mess. Waddling rapidly like a distressed penguin, emitting every now and then some strangely strangulated 'eeeeh,' 'aaahh' and 'oooh' noises, he struggled on up and down several crowded streets, breathing heavily, until he found a rather old-fashioned-looking department store. It would, he knew, have to do.

Wiping his flop-sweat furrowed brow, and clenching just about anything he had that would still clench, he entered shyly, almost coyly, looked one way and then the other, like a bad spy, and then waddled up to the counter, and asked, with all the faux-calmness that his volcanic-rumbling body would now allow him still to affect, to buy a pair of trousers and a pair of underpants. The elderly, rather skeletal-looking, bespectacled man serving him, sensing discreetly that his customer was in some kind of physical distress, took the payment promptly and assured him that, within the next ten minutes, the items would be selected, wrapped and placed ready for him to collect.

Hobbs, nodding gratefully if twitchily, waddled back out the door - he was painfully aware that there was, by now, to put it politely, something of a 'hum' hovering about him - and waited on the pavement in the open air. When the allotted time was just about up, he waddled back in, collected the package, wrapped neatly in thick brown paper and tied securely with string, thanked the staff and waddled back out.

He arrived at Waterloo later than planned, just as the rush hour was beginning, so he got his ticket, stepped up - extremely carefully - on to the train, shot straight into one of the toilet cubicles, locked the door and waited for the whistle to blow and the beginning of the journey home.

Once the train had left the station, the now utterly shattered, yet strangely relaxed-looking, Hobbs breathed a huge sigh of relief, peeled-off the offending trousers and pants, rolled down the window and threw them out. Then, after cleaning himself up, he stayed still, sighed again, rolled his eyes, rubbed his face, and, with immense gratitude, opened the package.

He could not quite believe his eyes. In fact, he could not at all believe his eyes. He stood there, swaying slowly from side to side as the train clattered on, utterly stunned.

Inside the brown paper parcel was not his freshly-purchased pair of trousers, nor his freshly-purchased pair of underpants. The only thing that was there was a woman's fluffy pink cardigan.

He felt like crying. He stared at the strange garment, eyes wide open, mouth gaping, hung his head down and breathed out almost a kind of deathbed exhalation.

He looked back up. He blinked. It was still there.

The trousers and underpants were still absent. He did that strange irrational thing of looking up, down and around as if they might simply have slipped out, unnoticed, and were just hanging about waiting to be discovered.

He stared again at the unfolded brown paper. Nothing but pinkness inside. He felt even more than ever like crying.

The train rattled on. Hobbs stood there swaying from side to side, in a deep kind of daze. Occasionally another passenger would tap at the door and try the handle, anxious to use the facilities themselves, and then walk away again, muttering in anger and frustration. Stops were taken - Fleet, Farnborough, Brookwood - the muffled sounds of people getting off and getting on were heard, more platform whistles echoed in, and then the journey continued, with Hobbs, blank-faced as if hypnotised, still locked in his own daze.

Then, finally, perhaps shaken by a sudden whistle or a jerking of the train or by another knock on the door, he suddenly came back into full consciousness. Looking out of the window, he could tell he was getting close to his home station. Something would have to be done.

He thought of his own discarded trousers and underpants, now probably hanging from some rail-side hedge or tree, swaying in wait to traumatise some innocent passerby as they paused to breathe in the fresh country air. He shivered at the thought of it.

Then, clenching his fists, he made himself face up to the harsh reality of the situation in the here and now. The train was soon going to stop. He would have to get out. He would have to find a way.

There were more deep breaths, more eyebrows raised, more eyebrows lowered, more puffing of the cheeks, and then, after enduring a stern internal talking-to, he did it. He picked up the pink cardigan, held it out low and upside down in front of him, pushed his right leg down one arm, pushed his left leg down the other, and pulled the whole thing up.

It looked ridiculous. He was ready for that. He was not an idiot. The outstanding problem was, however, that, even with all the buttons now buttoned up at the front, there was still a certain protuberance there where the neck usually was.

Panicking - the train was now getting very close indeed to his station - he grabbed his hat (in those days, he rather liked, mimicking his favourite movie stars, to wear a trilby) and manoeuvred it so that, to anticipate the later public transport mantra, he minded the gap. Then all he could do was wait and watch as the train slowed, the chug-chug of the engines eased up, the brakes hissed, and, at long, long, last, it was time for him to depart.

He waited, of course, for the crowds to disperse. He stood on the inside of the cubicle door, listening, sighing, praying. Then, when the noise died down, he took a deep breath, bit his lip, opened up the door and went out.

He knew what he had to do: walk quickly, purposefully, head down, eyes fixed on the floor, heading straight for the exit. He knew how absurd it must have looked: smart sky-blue tie, white shirt and nut-brown tweed jacket, with a pair of fluffy little pink legs whirring away underneath. He had only one thing on his mind: 'Don't look at anyone, don't listen to anyone, don't speak to anyone - just keep moving'.

It was only as he neared the longed-for exit, to the toot-toot-toot train sound of his release, that what, in his feverish state, he had actually - sort of - convinced himself was a semi-effective cover now appeared, devastatingly, to have been blown. The long-serving, long-faced station master looked up and noticed him.

'Evenin' Mr 'Obbs,' he said with a heavy-lidded look in Jack's direction. 'Been on 'oliday, I see?'

It did not surprise Hobbs that Milligan found this emotionally shattering story of his misfortune so funny. He had only shared it because he had really wanted to see one of his comedy heroes double up with laughter at something he had said. He was delighted, therefore, at the sight of Spike, sliding off his chair, hugging himself as he sat on the floor, with tears rolling down his cheeks, unable to stop laughing.

What, horribly naively, Hobbs was not quite expecting was to hear Spike, later on, go on to re-tell the story to just about anyone that he met. He told everyone else in his offices at Orme Court. He told strangers he encountered in pubs and clubs, in restaurants and on the street. He told all of his famous friends.

Then he started telling the story on radio and television as well as in his own one-man theatre shows. Whenever he was booked for a talk show, and felt bored or anxious or tending towards the depressed, he always departed from the arranged order of anecdotes, and reached for the sure-fire winner of the tale about his dear old friend Jack ('I promise you it's a true story,' he'd always say. 'Look him up in the phone book - H for Hobbs - call him and ask him!').

Even though he knew, better than anyone, that the story, just like Jack's undergarments, required absolutely no adding-to, he often gave in to comic temptation and added something anyway. Once he had actually told the story, rather than feel that, in that context, he had used it all up, he simply revised it sufficiently that he could tell it all over again.

Sometimes his version of the story was set properly in Cyprus, but sometimes, as the mood took Milligan, it was relocated to somewhere else, such as Greece, or Morocco, or Egypt, or Ibiza, or Portugal, or, on one especially strange occasion, it revolved around an elaborate odyssey to Oslo in honour of the art works of Edvard Munch.

In some of these re-tellings, Jack had been to Corfu, hauled up a billfish as he dangled his feet in the Ionian Sea, tried grilling the catch over the twigs and stones on a makeshift barbecue and, after rashly consuming the half-cooked creature, ended up 'spewing all the way home'. In other fanciful iterations, Jack had succumbed to a dodgy hotel shrimp dip on his final day away, or had been challenged to a chorizo-eating contest by a large and mysterious man in a fez, or had suffered an allergic reaction to his first taste of halloumi, or had escaped all possible infections throughout the whole stay and only started to experience any gustatory problems at all after ingesting an already curling open-faced sandwich on the flight back home to Britain.

This was the Faustian price that Jack Hobbs had to pay for surrendering his story, on that wine-woozy night, in order to make Spike Milligan laugh. It would seem to him, at times, as though the whole nation, maybe even the whole world, was laughing at the thought of him, Jack Hobbs, sans trousers, sans pants, but now cardigan-clad, mincing down the platform of a provincial train station.

For other people it would have remained a shiveringly shameful secret. For Jack Hobbs, it would always be an open access showreel.

Jack died in 1993. Spike would live on until 2002, still telling that story all the way to the end. Jack sensed that would happen. He felt that his friend was probably immortal. He feared that the story they shared was almost certainly immortal, too.

He got over it, sort of, before the end. 'Think about it, Jack,' Spike had pointed out to him, repeatedly, by way of reassurance. 'Being remembered for having a shit is a far, far, better thing than being remembered for being one'.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more