It Just Is Cricket: British comedy's sport of choice

Why is it that cricket is so much more amenable to comedy than any of our other major sports? Football, as the nation's most popular sporting past-time, surely ought to have figured high in terms of comic homages, but, in spite of its own best recent efforts with VAR ('Why, that's very nearly an armpit!'), it remains strikingly under-represented, as do rugby, tennis, athletics and most other major sporting activities (except golf, which has been over-represented historically to no one's great satisfaction except for golfers). Cricket, however, is a context in which comedy genuinely seems comfortable.

In movies, for example, it has given us the iconic comic characters of Charters and Caldicott (played so beautifully by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne), first in Hitchcock's The Lady Vanishes (1938), and then in numerous other productions and sometimes (for contractual reasons) under different names, culminating in the very entertaining It's Not Cricket (1949) - a film that managed to combine a 'dangerous Nazi', a stolen diamond, two hapless private detectives, a subversive sports shop, a doctored Dukes ball and a friendly one-dayer. The sound and sight of willow hitting leather was also much in evidence in Badger's Green (1934 and then re-made in 1938 and 1949), which saw a redevelopment project challenged via a game of village cricket; The Final Test (1953), whose plot centred on an ageing cricketer and his son; and Playing Away (1986), about a Brixton-based team made up of Jamaicans invited to play English village cricket.

It has been much the same in television, where the game has featured in plenty of sitcoms, sketches and plays, usually to good effect. Both Monty Python and The Goodies dipped into the sport on several occasions for some memorable routines; the gentle comedy Outside Edge, which followed two couples whose lives were entwined only through their involvement with the local cricket league, ran for three very successful series between 1994 and 1996; probably one of the strongest episodes of the Are You Being Served? sequel Grace & Favour was The Cricket Match in 1993; and Keith Waterhouse's 1985 BBC series, Charters and Caldicott, reprised the familiar film characters for an amusing small screen mystery (which was even more amusing if one saw the rather surreal 'cricket for beginners' introductions drawled by Vincent Price when the series was shown in the US as part of its Masterpiece Theatre showcase).

Football, by contrast, has always struggled to find the net as far as comedic success is concerned. The relegation form sported by the BBC's recent sitcom The First Team (2020), in spite of having excellent production and writing personnel pushing it on, was merely, to mix up the sporting terminology, par for the course.

The two glorious exceptions to the rule that are the 1973 Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads? episode No Hiding Place ('Don't answer that phone!') and the 1979 Ripping Yarns episode Golden Gordon ('Eight one! Eight bloody one!') - both of which, strictly speaking, were really about football fandom rather than about football itself - the game has accumulated a veritable Sergio Ramos-sized pile of yellow and red cards over the years for its clodhoppingly mistimed attempts at tackling comedy.

Why is this? Why has cricket outscored the other sports so highly when it comes to complementing comedy?

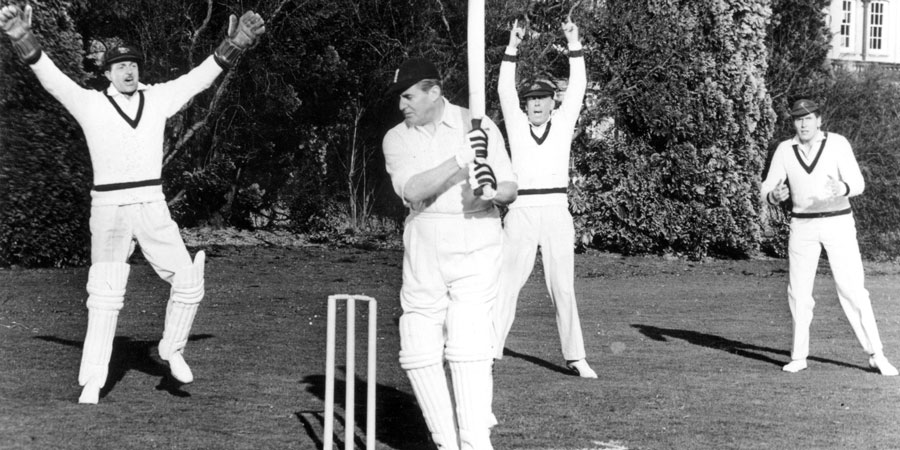

One reason is surely the fact that it is easier to make a cricket match look reasonably believable. A football game, like a number of other sports, is simply too much of a young person's activity - fast-moving and athletic, with plenty of physical contact - to ever look convincing when copied even by relatively fit and youthful actors, and is not worth even being attempted by more elderly performers. A cricket match, on the other hand, can work whether the actors are sprightly twenty-somethings or rather doddery senior citizens, and the 'action' can be more easily balanced between the odd delivery or drive and some conversations in the covers and some sledging from the slips.

Another reason is that cricket is simply the more naturally characterful sport. There is time and space enough, at the more leisurely levels of the game, for personality and dialogue to dominate the proceedings. Pacier sports suppress the comic character; cricket, at least in its most traditional forms, cultivates it.

Take the England Test teams of the 1970s, which managed to accommodate such richly diverse personalities as the preternaturally self-absorbed opening batsman Geoffrey Boycott; the tall and gawkily extrovert all-rounder Tony Grieg; the ancient-looking and bespectacled bouncer dodger David Steele; the fidgety and pixie-like wicket keeper Alan Knott; the pre-Enlightenment self-belief of Ian Botham; the disarmingly eccentric batsman and fielder Derek Randall; and the waddling escapee from the Home Office with the Stan Laurel face that was the fascinatingly unorthodox medium-paced spin bowler Derek Underwood. It was no wonder that a trained psychoanalyst, Mike Brearley, ended up in charge of them - it was either him or Will Hay.

Indeed, the range of characters who have kept on coming, from the languid, Tiger Moth-flying, unapologetic bon vivant David Gower to the prickly brilliant one-man cabal that is Kevin Pietersen, suggests that the Chairman of Selectors really ought to be casting sitcoms. It is often not clear which activity is the training ground for the other, but the sense of cricketers and comic characters being kindred spirits is exceptionally strong and sharp.

Cricket has also been such a powerful magnet for a certain type of English person - the type who is addicted to the minutiae of a particular culture and community, who adores rules and regulations and the devotion and debates they inspire - that it practically generates potential comic characters as a default position.

Michael Palin and Terry Jones recognised this fact when - in a sketch for The Secret Policeman's Ball (1979) - they came up with the pathetic figure of Will Bowes, a man whose orderly and cosy cricketing world starts to fall apart from dealing with too many inexplicably ignorant questions:

PALIN: Hello and welcome to another edition of How Do You Do It?. Tonight, Will Bowes has come along to tell us how to play cricket. Hello Will.

JONES: Hello Michael.

PALIN: Now, you've played for Gloucestershire for the last eleven years, Will.

JONES: Sussex, yes.

PALIN: And I'm not too good on cricket facts myself but I believe you've scored over a thousand runs in your career?

JONES: Fifty-eight thousand, yes.

PALIN: And you also bowl ganglies?

JONES: Googlies.

PALIN: How do you play cricket, Will?

JONES: Well, Michael, the first requirement is a pitch, which is-

PALIN: Can I stop you there?

JONES: Er, yes?

PALIN: What is a 'pitch'?

JONES: Well, a pitch is a piece of ground, er, preferably flat - although I can think of quite a few that are sloping at all angles!

PALIN: I see, yes - so the pitch needn't be flat?

JONES: Er, well, no, it's better if it is flat, yes.

PALIN: What do you do on the pitch, Will?

JONES: Well, you have what are called 'stumps' -

PALIN: Sorry, can I interrupt you there, Will? Who has the 'stumps'?

JONES: Well, everyone has the stumps.

PALIN: I see. You all have stumps. But what we really want to know now, of course, is: what do you do with the stumps when you've got them?

JONES: Well, you stick the stumps in the ground.

PALIN: Ah. Is the 'ground' the same as the 'pitch'?

JONES: [Getting exasperated] Well, no, the ground is the whole playing area and the pitch is the bit in the middle.

PALIN: I see. So you don't stick your stumps in the pitch?

JONES: Y-yes, y-you do!

PALIN: Ha ha, you're getting as muddled as I am, aren't you, Will!

JONES: No, I'm not, no!

PALIN: What happens now, Will?

JONES: Well, you have what are called 'bails'.

PALIN: Balls.

JONES: No, no, no: bails.

PALIN: No, Will, I don't know much about cricket myself but I think you'll find they're called 'balls' and-

JONES: No! You have one ball and four bails.

PALIN: I see. So let's just clear this up, Will: so you have four bails in one over, is that right?

JONES: No, no - that's balls. You have six balls in one over.

PALIN: I see. So you were wrong about the bails?

JONES: No I wasn't wrong about the bails!

PALIN: Ha ha ha, don't worry, Will, I'm always getting things wrong!

JONES: No! I wasn't wrong about the bails!

PALIN: What are 'runs', Will?

JONES: I'm still going on about the bails!

PALIN: Tell us about 'runs', Will.

JONES: No!! I want to talk about bails!!

PALIN: You've told us about the bails, Will - tell us about the runs.

JONES: I want to talk about BAILS!!!

PALIN: Are 'runs' the same as 'scores'?

JONES: I WANT TO TALK ABOUT BAILS!!! [Storms off the stage shouting] IT'S BAILS, D'YOU HEAR? IT'S BAILS!! THAT'S THE ONLY THING THAT COUNTS IN CRICKET!!!

PALIN: Well, that's all for this week. Next week on How Do You Do It? I'll be speaking to the president of the Chinese People's Republic on how to rule 900 million people. Goodnight!

The sight of someone losing control, like Will, is grist to the mill in comedy; the humour comes from the hubris. Cricket - much like economics - is a game that looks like it can be mastered when pondered on paper, but, once experienced in practice, a succession of often maddeningly unpredictable, and sometimes unmanageable, variables - the climatic conditions, the sudden loss or finding of form, the odd accident or injury, the animal spirits of individual players, and so on and so forth - threaten to send any control freak insane.

It is no surprise, in this sense, why cricket has proven a perfect sport for such classic sitcom control freaks as Dad's Army's George Mainwaring and Ever Decreasing Circles' Martin Bryce. Here are two Englishmen whose whole fragile world is held together by a fierce belief in everyone following the right rules in the right manner, and putting the team before the individual - so long as the team is led by the right individual: namely, either of them.

A cricket match captures their madness in microcosm. They expect life to be like a well-played and well-umpired game, and then find that not even a game goes, for them, the right way. Rules are bent, respect gives way to irreverence, accidents keep happening, chaos replaces order, and this couple of self-appointed captains are left raging at the unfairness of life.

The Dad's Army episode that illustrates this so memorably is The Test (1970). It is the episode, more than any other, which takes the viewer right inside Mainwaring's brain for the duration.

The ARP wardens have challenged the Home Guard to a game of cricket. Mainwaring's players are up for it - even the dreamy-eyed Gower-like Wilson - but Mainwaring himself ('I used to be a passable opening bat') is really up for it: this is his best chance, short of dealing with actual Nazis, to reaffirm his vision of the right and proper form of life ('We're walking out here as free men to play a friendly, British game,' he declares. 'That's what we're fighting for, you know!').

Right from the start, as Mainwaring promptly appoints himself coach, as well as captain, of the team, it is strikingly evident that his unquestioning attitude to cricket mirrors his unquestioning attitude to military life:

MAINWARING: When you're playing back to a short-length ball - thus - in any case, you always keep the bat absolutely straight.

WALKER: Why?

MAINWARING: Why??

WALKER: Yeah - why do you do that?

MAINWARING: Because that's the correct way to do it!

The polar opposite in Mainwaring's Manichean world is the brash, boastful, dirty-fingered greengrocer Hodges, the leader of the opposing team. Hodges is ready to do whatever it takes - bend or break any rules, nobble the umpires and even hire a ringer (E. C. 'Ernie' Egan, a world class, fire-breathing, ferociously fast bowler, played by the real ex-England quickie Fred Truman) - in order to win the game.

Sure enough, once the game begins, things start to fall rapidly apart for Mainwaring's men. The captain's rash decision to open the bowling himself with a succession of limp-looking lollipops soon sets the scoreboard clicking ('Don't bother to run singles, Gerald!' cackles Hodges); Jones the wicket-keeper causes chaos by smashing the wicket after every delivery; Fraser, inevitably, starts sowing the seeds of unrest amongst the slips ('This is more than flesh and blood can stand!'); Godfrey doesn't just fail to catch the ball at the boundary's edge but also promptly loses sight of it in the undergrowth, thus allowing the batsmen to run twenty-four times in its absence; and (anticipating the infamous real-life Mike Gatting-Shakoor Rana altercation) the verger, acting as one of the umpires, starts betraying more than a slight degree of bias:

VERGER: No ball!

MAINWARING: That was my googly!

VERGER: Well, from where I was standing it was a chuck! And don't argue with the umpire or you'll be sent off.

MAINWARING: You don't send people off at cricket!

VERGER: I do!

MAINWARING: I suppose I'm very lucky not to have been given offside!

VERGER: I'm taking your name for that! 'Mainwaring: for gross impertinence and sarcasm'!

Nothing, however, is going to deflect Mainwaring from pursuing the straight road ahead to a virtuous victory. He merely requires ten other round-headed and short-haired Englishmen ('You're not a violin player,' he admonishes the loosely-trimmed Wilson), wearing proper caps, with their own white flannels ('Trousers are a very personal thing, you know - not to be bandied about') and a proper respect for the rules in order to end up triumphant.

Actually, he also needs - not that he would ever admit it - quite a bit of luck: Ernie Egan breaks down with an injured shoulder after bowling just one hair-partingly blistering ball; Wilson gets away with more than a few casual wafts outside off stump; and Godfrey ('I'd be delighted to oblige in any capacity that doesn't involve too much running about') somehow contrives to hit the winning six. The victory, as far as the somewhat dazed Mainwaring is concerned, is one more confirmation that he is playing the game the right way: 'We're ready for any challenge,' he tells a disheartened Hodges, 'whether it comes from you or across the channel!'

If there is one person, however, for whom cricket speaks from the soul more profoundly than it does even for Mainwaring, it is surely Martin Bryce. Ask of him the question, 'What do they know of cricket that only cricket know?' and, after a brief puzzled squint, he would probably hit you on the head with the latest edition of Wisden.

Even without the wartime context that helped keep Mainwaring's mind so forcefully focussed, Martin has been able to grow up, in his own strange way, guarding his way of life as doggedly as he would his wicket, and vice-versa.

The Ever Decreasing Circles episode that shows just how dangerously committed he is to finding a meaning to life in the game that he adores is, unsurprisingly, The Cricket Match (1984). This is a much darker, more alarming insight into the power of sport than Mainwaring's storyline, because, in Martin's case, it is his inability to control a particular cricket match that reminds him so cruelly of his inability to control his culture, his community, his cul-de-sac and himself.

The story centres on a forthcoming big game. It is not really a big game, it is really a small game, but it is a big game for Martin, because all games are big for Martin.

Martin has run his local cricket club for fourteen years. He has done everything for his local cricket club. He has played for it, tended the ground for it, looked after the kit for it and organised the fixtures for it. He basically is his local cricket club.

His dearest ambition is to take his club up to a higher division - 'in with the cream' - where they will play better opponents at venues that have dressing rooms with oil-fired under-floor heating. 'We could play Branston Pickles,' he says wistfully. 'Jeyes Fluid...The Coal Board...' It is this dream of being in with the cream, however, that threatens to drag him down ever deeper towards a dreaded Faustian deal.

He is just enough of a realist to know that his beloved team, boasting as it does such 'key' players as Martin's happily fatalistic next-door neighbour, Howard Hughes, whose much-cherished top score is a pathetic eleven ('I just had one of those magic days'), is not up to the task unless it gets at least one much better player. The nearest much better player, and the man whom Martin knows can help him realise his dream, is his next-door neighbour, Paul.

Paul is everything Martin is not. Paul is a handsome, urbane, well-educated and witty man who seems to excel at everything without even trying. Martin is a plain-looking, under-educated, humourless valve salesman who has to work really hard at anything just to be even adequate. What makes it even worse is that Martin suspects that his long-suffering wife, Ann, secretly fancies Paul.

Logic keeps pushing Martin's no-nonsense ballpoint pen towards writing Paul's name down on the team sheet, but pride keeps pulling it back. 'He's actually played at Lord's,' he groans. 'Faced county bowling. Probably better than the rest of us put together!' Ann thinks that she understands, but he insists that she doesn't. 'I don't mind him being better at cricket than me,' he protests. 'I don't mind that. It's the way he'll be better!'

Triumphs must be transparent for Martin. He needs to see steps for progress; he needs to see rungs. Achievements cannot be mystical. That would render his whole world meaningless.

He can understand grafting to glory. He cannot grasp gliding to glory.

That's the problem with Paul. He glides. 'I bet he doesn't even have to comb his hair when he gets up in the morning,' Martin rages. 'I bet it just falls into place on his head!'

Desperate to keep the universe in order, he tries to persuade his regular teammates that it would be best if they resisted mixing some magic in with the mediocrity. 'Would it really be morally justifiable to pick Paul for the team?' he asks hopefully. 'No problem at all,' replies Howerd cheerfully. 'Any one of us would stand down to give Paul a game!'

It gets worse when Paul pops round for a chat. It always gets worse for Martin when Paul pops round for a chat:

PAUL: Hello Martin.

MARTIN: [Busy with his printing] What? Ah, oh, come in, Paul. Just, um, dashing off a few appendices. [Paul picks up a copy from the pile, but Martin snatches it back.] All in due course - they'll be in the post.

PAUL: You're going to post me one?

MARTIN: Of course.

PAUL: But I only live next door - couldn't I just take one with me?

MARTIN: No, I'd sooner they all went with the post, thank you. They're just a rationalisation of the 15p increase in cricket subs this season.

PAUL: I see. Well, you needn't bother to send me one now.

MARTIN: Why?

PAUL: You've just told me what they're about.

MARTIN: Oh Paul, I DO wish you'd put your wheels in the same tramlines as everyone else!

Martin can barely stand even to look at Paul. It's Paul's smile. It always strikes Martin as more of a smirk. Perhaps it is.

Staring at a safe bit of empty space, Martin, struggling to control his emotions, informs Paul with a grimace that he has indeed been picked for the cricket team ('You'll be getting a postcard from me to that effect'). Paul accepts graciously, but Martin hasn't finished with him yet.

Martin proceeds to try his best, in his usual awkward way, to explain to Paul how things really are. He does so by citing his cricketing hero, Denis Compton.

Denis Compton, Martin points out, was captained at Middlesex by F.G. Mann. 'Not so great a player, not by many a long chalk,' he acknowledges, 'but nevertheless he was his captain.' Martin is now fixing Paul with a telling stare. 'Never - ever - did you see Denis question FG, slight FG or demean FG in any way whatsoever.'

He hopes that the message has been delivered, only to be disappointed. 'What are you trying to say?' Paul asks, disingenuously. 'I'm not trying to say anything,' says Martin testily. 'I'm not a person who tries to say things! I say what I have to say!' Paul looks at him sweetly: 'But what are you saying?' Martin can hardly believe it: 'I'VE JUST SAID IT!!!'

This torment seems to suddenly be over after Paul points out that, as the first game of the season is on a Saturday rather than a Sunday, he can't play, because he has the VAT man coming round to his business. Martin can hardly hide his elation. 'So you'll send the postcard back saying that you're unavailable then?'

Come the day of the game, however, and Martin finds himself plunged back towards Hell. Paul's turned up unexpectedly, and he's wandering around inside the changing room. Martin, just like Mainwaring, is horrified at such an intrusion: 'Do you realise there are people's private trousers hanging on hooks in those dressing rooms?'

It is the perfect storm for poor Martin. The VAT man has postponed his visit and so Paul is free, Howard and the others are eager for him to play, and Curly Baldwin has just broken a finger in the warm-up. There is no choice but to play Paul.

Martin, however, is still not ready to surrender control. He stubbornly allows the opposition to stack up a formidable score of 189 for 3, just because he refuses to let Paul bowl. He then keeps Paul stuck low down the batting order ('I'm holding him back, just in case') as he goes ahead and tries to grind out a captain's innings, but at 46 for 7 Martin himself gets out in farcical circumstances. Then, from beyond the boundary, all he can do is stand alone in the shadow of an old tree and watch helplessly as Paul strolls out and glides his way to a century and clinches a famous victory.

The aftermath of this experience is devastating for the captain. While Paul's back is patted by all and sundry in the club bar, Martin sits alone in his blazer, arms folded tightly, staring at the steaming ruins of his shattered world.

What makes it even worse is that the opposing skipper thinks that he actually wanted to conjure up this chaos: 'That bloke who won the match for you - I found out he played for Cambridge University. Look, I always thought that this league was for people who weren't very good at cricket but who enjoyed the game. In my mind, any captain who is so keen on winning that he picks someone of that class is nothing but a cheat!'

Now utterly crushed, Martin is comforted by Ann, who persuades him to go back into the bar, start playing the piano, and lead everyone in a sing-song. Before they can get inside, however, the sound of someone else playing the piano strikes up. She opens the door, peeks in, and shuts the door again. 'Yes,' she tells him, sheepishly, 'it is him.'

Martin just nods. He just nods and looks off into another precious Paul-free space.

The whole episode is a mini-masterpiece of an account of what cricket can do so cruelly to certain kinds of character. Cricket becomes both a playground and a prison to them, a context in which they can clash and collaborate and compete but never leave - which is very much the same experience as the characters have in a sitcom.

The whole episode, with its brilliant writing by John Esmonde and Bob Larbey, and its equally brilliant acting by Richard Briers, Peter Egan, Penelope Wilton and all the others, is also a supreme demonstration of what comedy can take as a catalyst from cricket. All of that hope, all of that uncertainty, all of that despair, all of that horribly vulnerable human life: you would not get it that richly from any other sport.

Plenty of the other activities can do much better, in comedic terms, and one hopes sincerely to see them try, but cricket remains rather special. It can thrill you, intrigue you, bore you and beguile you, but it is also unusually good at making you laugh - and that, no matter what the more dour followers of the game might say, is never a negative thing.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreEver Decreasing Circles - The Complete Series

Written by the successful team of John Esmonde and Bob Larbey, Ever Decreasing Circles was first broadcast by the BBC in February 1984. Richard Briers, Penelope Wilton and Peter Egan star in this popular suburban-set comedy.

This box set features all four series of the hit comedy show.

First released: Sunday 15th April 2007

- Distributor: Cinema Club

- Region: 2

- Discs: 5

- Catalogue: CCTV30596

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Outside Edge - The Complete Series

Features every episode from the television comedy series that follows the going-ons of a village cricket team, and the diverse individuals associated with it.

First released: Sunday 8th July 2007

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 4

- Catalogue: 7952834

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Sunday 6th April 2008

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 4

- Catalogue: 7952834

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Sunday 6th April 2008

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 4

- Catalogue: 7952834

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Tuesday 5th August 2003

- Region: 1

- Discs: 2

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Dad's Army - The Complete Collection

Captain Mainwaring, Sergeant Wilson, Corporal Jones and Privates Pike, Godfrey, Walker and Frazer are back in this complete series boxset - enjoy the endeavours and hilarious antics of the Walmington-On-Sea Home Guard!

This box set contains the complete series: One, Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven, Eight, Nine, The Christmas Specials and all 3 surviving episodes of Series 2, plus a great selection of extras including the radio adaptations of the 3 Series 2 missing episodes.

First released: Monday 29th October 2007

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 14

- Catalogue: BBCDVD2254

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Playing Away

Late 1980s comedy following the charity match between an inner-London cricket team comprised of West Indian immigrants, and one from a sleepy typically English country village.

First released: Monday 26th May 2008

- Released: Monday 26th October 2009

- Distributor: BFI

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Catalogue: BFIVD850

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Catalogue: ORB10144

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

It's Not Cricket

It's Not Cricket is a post-war comedy produced by one Britain's finest comedy talents: Peter Rogers, and his future wife and probably the finest female producer of her generation, Betty E. Box.

Major Bright (Basil Radford) and Captain Early (Naunton Wayne) are two helpless intelligence officers in the British army in post-war Germany. Sent back to England for a spot of leave they fail to notice that their new batman is actually war criminal Otto Fisch (Maurice Denham) and when he vanishes the two officers are quickly demobbed.

Back on Civvy Street our two heroes set up a private detective agency, Bright and Early. When they are invited to a weekend country house party for a cricket match they stumble across a robbery plot involving a diamond that Fisch has stolen. Will the two helpless detectives finally catch Fisch and recover the diamond?

First released: Monday 24th March 2014

- Distributor: Strawberry Media

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Catalogue: STW0076

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Lady Vanishes

Celebrated for his suspense-packed thrillers, macabre plots and twist endings, Alfred Hitchcock is one of cinema's greatest auteurs. He directed over 60 films throughout his career and The Lady Vanishes is one of his most significant pre-war British films. Starring Margaret Lockwood and Michael Redgrave, this digitally restored version of the film has never looked better.

Intrigue and espionage abound when a young woman travelling aboard a trans-continental express train strikes up an acquaintance with a middle-aged english governess who then disappears. is the young woman hallucinating or is it something altogether more sinister...?

Special features:

Introduction to The Lady Vanishes by Charles Barr

Original theatrical trailer

Image gallery

Script PDF

First released: Sunday 17th August 2008

- Released: Monday 19th January 2015

- Distributor: Network

- Region: B

- Discs: 1

- Catalogue: 7957077

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Catalogue: 7952920

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Final Test

A cricketer looks forward to his last test match, but is astonished to learn that his son would rather write poetry than watch his innings. Real-life cricketers of the day make appearances. The screenplay is by Terence Rattigan.

First released: Monday 6th August 2007

- Distributor: Odeon Entertainment

- Region: All

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 87

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.