Taking on the tabula rasa: Inside the writing room

Writing comedy. Some like to do it standing up; some prefer sitting down; and others have ended up lying flat out on the floor. It's important, as Frankie Howerd often said, to get yourself comfy, and certainly the best shapers of scripts have relied on their own tried and tested working routines to start, and stay, typing.

It's all too easy to romanticise writing. The usual way is by imagining having written, rather than imagining trying to write. Trying to write is rarely fun. It can sometimes be a pain from which one strains to escape.

In the case of solo comedy writers, when faced with the bleakness of the blank page, the need for self-discipline has always been as vital as it's been fragile. Lacking a colleague to keep them committed, the lone author has to battle especially hard against the chronic threat of distraction (rather than go out once to buy half a dozen eggs, so the joke goes, the solitary writer will go out six times to shop for one egg), and it is thus not uncommon for the psyche to split into two, with one part acting as prison warden to the other part's restless prisoner.

In some cases the pressure comes from another presence. Eric Sykes, for example, was 'encouraged' to keep at it by his first client, Frankie Howerd, who used to lock him in a cupboard-sized room with only a desk, a chair, a typewriter and a cheap bottle of whisky for company. The comedian would only let the writer back out again once the latest script had been completed and, to prove it, slipped out under the door.

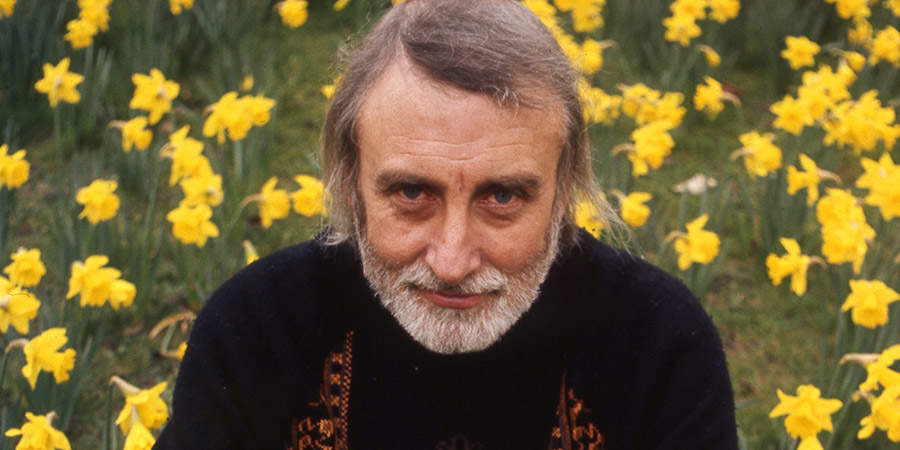

This externally-administered discipline must have gradually become internalised, because in his later years, once Sykes had won the right to an unlocked room all of his own, he continued to tap out material so promptly that he was free to leave and play golf in the afternoons. It was the kind of efficiency that would often send his colleague in the adjoining office, Spike Milligan, raging with a mixture of frustration and envy.

Milligan had recently teamed up with Sykes and Galton & Simpson to set up a writers' co-operative called Associated London Scripts (ALS) in a hive of offices above a greengrocer's shop in Shepherd's Bush. The move had been inspired partly by Milligan's desire to foster greater power for himself and his fellow professionals, but also in part because he hoped it would help combat his own sense of loneliness.

It proved far more effective at delivering the former than it ever did at achieving the latter. The busily rhythmic sound of typing emanating from the other offices only exacerbated his own anxiety when he felt as blank as the page that he faced, while reminding him that it was still possible to feel desperately lonely when there are plenty of other people around.

He did now have a secretary, Beryl Vertue, whom he shared with the other occupants of ALS, but, as he usually only had reason to see her at the end of the writing process, her presence seemed of little service in the sense of moral support. He was still alone in his office, and still struggling with his own demons.

Always a restless presence, Milligan took about as long to settle down at his desk as it did for Sykes to complete an entire script. He would contrive to find all kinds of other things to do during what was supposed to be his time for typing.

He fed, very frequently, the increasingly portly pigeons who perched outside his window ('Tuck in, lads'). He played darts, cards and carpet golf. He cleaned all kinds of things - pencil sharpeners, hole punchers, paperweights - that did not need cleaning.

Another all-too reliable means of distraction was attending to the regiment of box files that were stationed all along one of his walls. One box was for unused, but still useable, ideas; another was for his children's notes and drawings; one contained correspondence with old war comrades; another one stored troublesome bills. Anyone who sent him something that caused any measure of distress was banished immediately to the box file labelled 'Bastards'; once that file was filled to the gills, any fresh pests were deposited in a second box labelled 'New Bastards'.

Several factors were required to intersect before Milligan finally managed to find the right frame of mind for work. Silence was essential ('This door can be closed without slamming it', announced the sign outside his office. 'Try it and see how clever you are'). A period of peace with his various friends (such as Peter Sellers, whom he once attacked with a potato peeler) and employers (such as the 'run by idiots for idiots' BBC, whose bureaucrats he felt obliged to 'shake out of their apathy') was also highly prized.

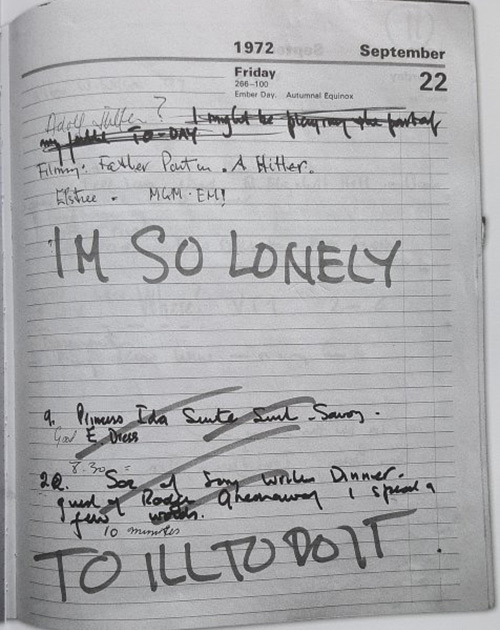

A quiet time for topical controversies was similarly desirable (an obsessive sender of missives to the national newspapers, he would sometimes devote the best part of his days to writing to them about abortion, vivisection and factory farming; the noise made by car horns, radios and lawnmowers; demands for the rapid and unilateral disarmament of nuclear weapons; urging Mao Zedong to stop encouraging the Chinese people to breed; and he also wrote to the then-Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, about - and with - a leaky pen). Most crucially of all, the many battles raging inside his brain had to have reached a ceasefire (his door was often decorated with such anguished declarations as: 'ILL!'; 'I'VE HAD ENOUGH - JESUS HAD IT EASY!'; 'I'M VERY VERY ILL'; 'I'M NOT IN'; and 'LEAVE ME ALONE!').

When he did, eventually, settle down and start typing, he disliked ever having to stop (to take a break was to invite a block, and the arrival of a block could be the harbinger of a breakdown). He wrote as he thought, and, if he came to a place where the right line failed to emerge, he would just jab a finger at the keys, type 'FUCK IT' or 'BOLLOCKS,' and then carry on regardless.

The first draft would thus feature plenty of such expletives, but then, with each successive version, the expletives grew fewer and fewer, until, by around about the tenth draft, with the wastepaper basket over-spilling and the balls of scrunched-up paper scattered all around his feet, he finally had a complete, expletive-free, script. Utterly exhausted, he then emerged from out of his office, looking like the drained Odysseus after returning from the Trojan War, clutching his finished script. 'It's done', he would announce with a huge sigh of relief. 'I'm going home!'.

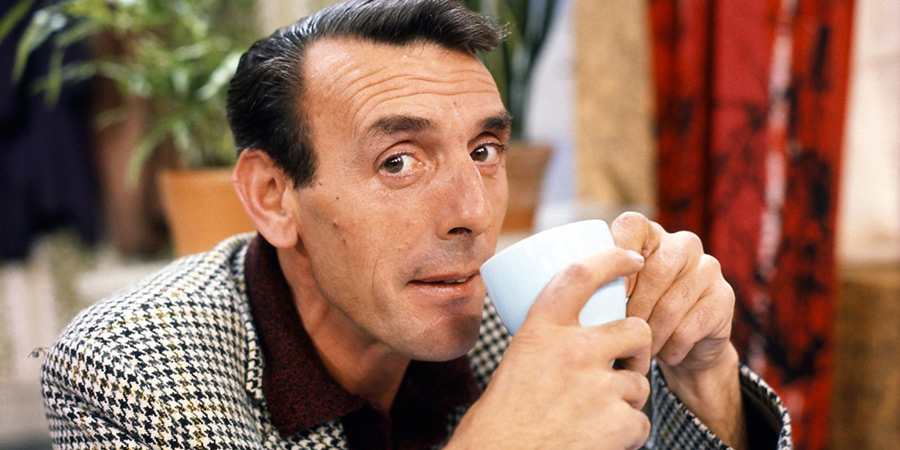

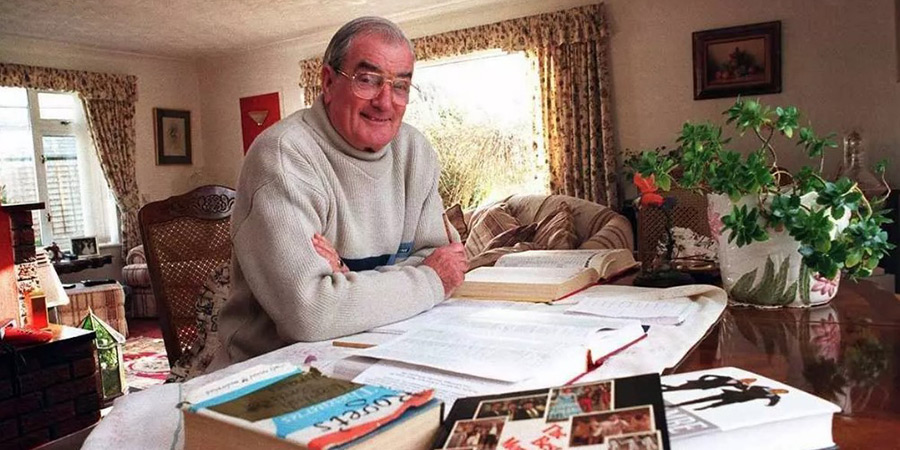

Someone else who was obliged to endure the loneliness of the long-distance writer was Eddie Braben. For the best part of thirty years, he was solely responsible for the scripts first for Ken Dodd and then for The Morecambe & Wise Show.

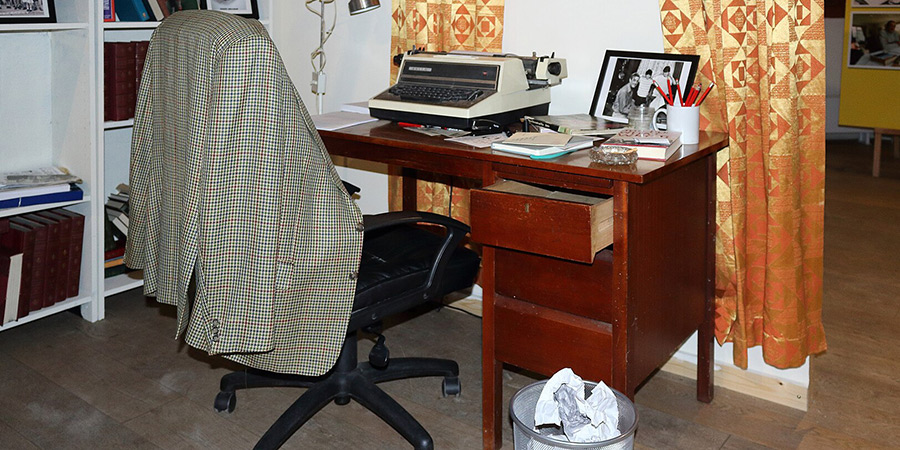

Seated at his battered three-drawer desk inside the study of his home in West Derby, Liverpool - with everything pushed up close to the radiator for warmth - he would stare at the blank piece of paper until he thought of something funny enough to type. Fuelled by strong tea and cigarettes, he would keep going - 'sweating blood', he would say, fourteen hours a day for three weeks - until, each time, he had a script that seemed good enough to be considered even better than the previous script. Then, with a heavy heart, he would set off to Lime Street to catch the train to London, where, at Television Centre, the stars were waiting to read what he had written.

'It wasn't London I disliked', he later told me, 'it was just going down to be judged. I was going down to be judged, and, deep down - I suppose every writer feels this - the fear was that someone was going to say, "This isn't even remotely funny! You're not a comedy writer - go home and take this rubbish with you!"'

The strain of being a solitary writer saw Milligan suffer several massive nervous breakdowns, and Braben succumb to a major one of his own. It tends, alas, to go with the territory: stuck in a room of one's own, labouring away at laughter, no one else can hear you scream.

That has to be one of the reasons why so many more comedy writers prefer to pursue their goals through partnerships. It's not just about sharing the passion; it's also about sharing the pain.

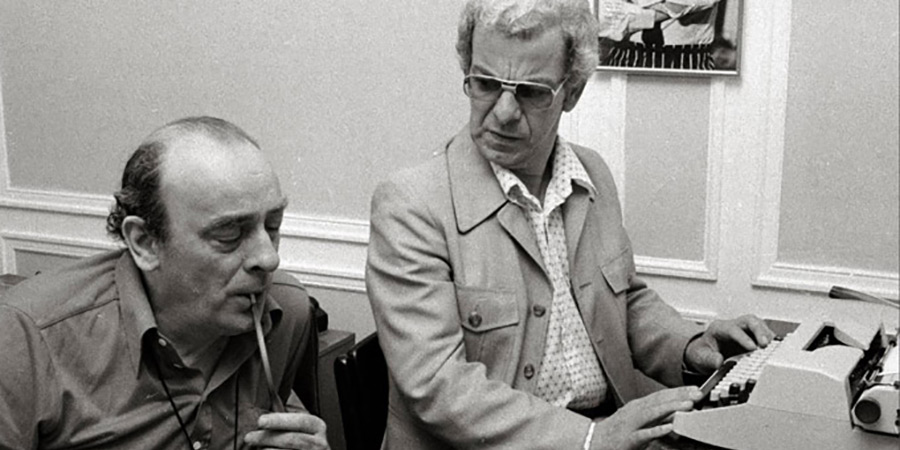

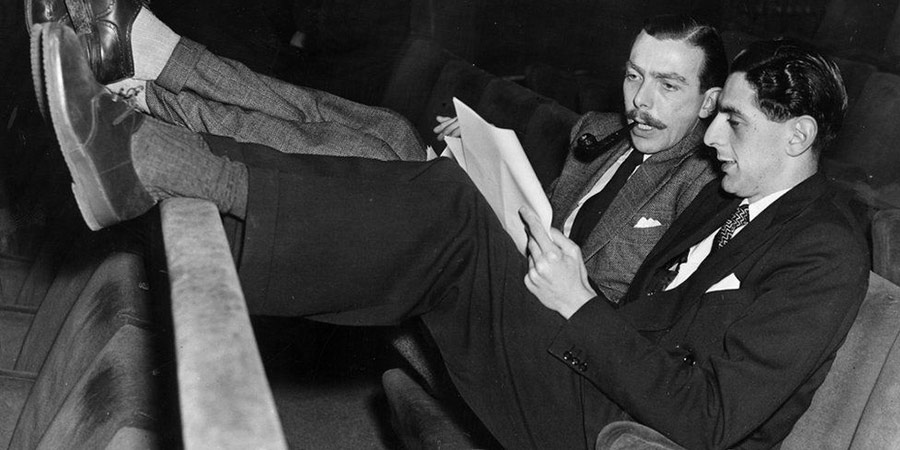

The pair who created the template for Britain's post-war comic partnerships were Frank Muir and Denis Norden. During a collaboration that lasted sixteen years, they were responsible for some of the biggest comedy successes of the era, most notably the long-running BBC radio show Take It From Here, as well as acting as consultants to the Corporation and mentors to the next generation of budding scriptwriters.

They started out by setting up an office in the Norden family's London flat, just to the north of Regent's Park. Once established as writing team, they moved on and based themselves at their agent's headquarters in Waterloo Place, and invested in a cheap second-hand 'partners' desk': a bespoke piece of wooden furniture that had knee-holes and three drawers on either side so that two writers could face each other while working on a script.

They felt comfortable at that desk. Each one employed the same filing system: the top drawer was for work in progress, the bottom was for work completed, and the middle was for indigestion tablets (which they regarded as vital because of their habit of gulping down hot bacon rolls for lunch when they were racing to meet their deadlines). Sitting back with their feet up on the top, they could look at each other's reactions as they talked through their latest ideas.

A sobering sign of how precarious partnerships could be would come when, after a couple of years of increasingly well-paid commissions, they decided to invest in a new desk. After searching in vain in London's various furniture stores, they switched their attention to some of the city's antique shops, where they realised just how scarce such items now were. 'They don't make them any more', one dealer explained. 'You see, there aren't that many partners about - there just isn't the trust'.

Their own partnership, nonetheless, went from strength to strength, with them still using their increasingly scuffed and scratched old desk. The working method they favoured saw them adopt the old American comic Fred Allen's motto, 'Dirty the paper', and start writing something - anything - to stop the sight of the blank page from intimidating them ('Once you've dirtied it', they said, 'you're in charge'). They then divided up the planned script between them, with each writing their own sections in longhand, and then passed the pages on to their secretary, who typed them up for review. 'The script takes on a sort of different character when it's typed', Norden would later explain. 'It helps us stand back and read it through fresh eyes'.

Their collaboration benefitted from their contrasts. 'Frank thinks all the best comedy is essentially kindly', Norden would say. 'I think all comedy, all jokes, all laughter, is a way of saying, "Thank God that wasn't me". In other words, it's essentially selfish'.

The clash of perspectives provided the friction that sparked the synthesis. What they created by coming together was something far richer and more interesting than the simple sum of the parts.

The union of Muir & Norden only came to a close when, after somewhat rashly accepting a lucrative offer to leave the BBC for ITV, and with their egos suitably preened, they promptly accepted a project that obliged them to perform as well as write (an adaptation for the screen of the popular book by George Mikes called How To Be An Alien), and experienced their first real critical failure. It hit them so hard that, all of a sudden, the supportive arm that they put around each other's shoulder no longer seemed to suffice.

'Collaboration is a funny thing', Norden would reflect on the shared sense of having outgrown their partnership. 'We used to sit across this desk, as I say, and two human beings weren't really meant to gaze at each other for that number of hours across such a small space'.

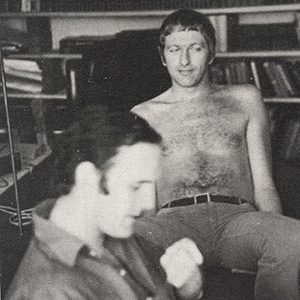

Muir & Norden were succeeded by the younger writing double act of Ray Galton and Alan Simpson. Theirs was a relationship that, unlike their predecessors, grew out of, rather than into, a context of confinement.

They met as teenagers while both spent the best part of three long years together in Milford Sanatorium, where they were convalescing from tuberculosis. Finding out that they shared a love of humour, they fought the daily boredom by listening to the radio together and then writing their own comic routines.

Once released from their prolonged captivity, the pair started collaborating on scripts in the little lounge of Alan Simpson's mother's house in Streatham Vale (Simpson, having been the first to learn how to type - albeit with one finger per hand - sat at a desk and took responsibility for transcribing the lines, while Galton - watched sleepily by Nigel, the family cat - stretched out on the carpet and stared at the ceiling). Encouraged by how well these initial sessions went ('Our sense of humour was almost identical', Galton later recalled, 'which meant that as soon as we started working together we became almost telepathic. We could finish off each other's sentences'), they wrote to Muir & Norden for advice and then began submitting material to the BBC.

Soon they were writing for variety shows, and then came into contact with Tony Hancock. By 1954, they had launched their first, hugely successful, sitcom, Hancock's Half Hour, and also moved in with Sykes and Milligan as co-directors of Associated London Scripts.

The two men took to coming in to ALS each day and camping down on the floor of their own capacious office (the curtains always tied wide open, with the bulbs beaming, maximising the light). Both would now stretch out their six-foot-plus frames across the threadbare carpet, position some drink and some cigarettes within easy reach, and then stare, and stare, and stare, until one or both of them came up with a serviceable idea (Simpson would still usually be the one who got up and typed it, because Galton protested that he was never too keen on the noise). 'We could go two or three days without talking to each other', Simpson would recall. 'We'd never say it was crap, we'd just grunt. If one said something and the other said nothing, then you knew you were wrong'.

There was no mess, no waste, with this pair: they were increasingly dapper men who produced increasingly dapper scripts, and when each one was done it was ready to be delivered. They were, as a consequence, the only writers during those early days at ALS who rarely took the opportunity to use Beryl Vertue as a sounding board: 'Spike would [sometimes come into my office and] read a script aloud, flinging his arms around doing all the voices', she later recalled. 'Eric would act [his script] out, playing the various parts, [whereas] Alan and Ray would just hand me the script without a word'.

Contentedly self-sufficient, they would roll lines back and forth, smoothing them out, until the sense and sound struck both of them as being precisely right. As Alan Simpson would later reveal about probably their most repeated phrase of all, from the Hancock episode The Blood Donor:

The line that went out was: 'A pint? Why, that's very nearly an armful!' Which gets a nice laugh. But Ray and I used to take care over rhythms. We used to spend a lot of time working out just how we wanted the sound of the line, the rhythm of the line, to be. One 'and' too many, one 'but' too many, one syllable too many, can kill a line. It's like poetry. So that line probably started out as: 'That's an armful!' Which in itself is quite an amusing concept - to talk about blood as being an armful or a legful. And then one of us probably said: 'That's nearly an armful!' Which is better because it's a little bit more precise. And then the other one would have topped it up by saying: 'That's very nearly an armful!' Now, 'very nearly an armful' is much funnier than 'that's an armful'. It's the same gag, but [the key thing is] being specific on a stupid way of assessing things.

Probably no British duo had a more fruitful, and friendly, writing partnership than these two men. For a quarter of a century, with shows such as Hancock and Steptoe And Son, they set the standard for comedy scriptwriting, and inspired countless other collaborations to follow in their footsteps. They only parted, professionally, when Alan Simpson decided to retire in 1978, but even after that, and indeed for the rest of their lives, they still met up every week to chat, finish off each other's sentences and amuse and advise other writers.

Galton & Simpson, therefore, represent just how good such unions can get. Sometimes, however, the writing relationship can prove as problematic as an ailing marriage. Take, as an example, the partnership between John Cleese and Graham Chapman.

It started promisingly enough, when the two of them were still students together at Cambridge ('We found each other funny', Cleese would later recall in his autobiography, So, Anyway, 'and when we did laugh, we really laughed, Graham screeching and me wheezing'). When they started collaborating professionally, their respective strengths meshed impressively, with Cleese strict on structure (always an A to B sort of thinker) and Chapman more eager to be unpredictable (his ideas - which sometimes came after staring at random words in Roget's Thesaurus - emerged untidily, and required far more editing, but could sometimes provide the inspired oddity that lifted the sketch to another level), but, as the pressures to keep succeeding grew increasingly intense, certain tensions began to creep in.

Competitiveness was one thing. Chapman once admitted that he had been having a pleasant dream about being appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, only to wake up abruptly feeling deflated after discovering that Cleese was his new Prime Minister. They could laugh that kind of thing off, for a while, but the imbalance in their input became, much more rapidly, a major factor in their in-fighting.

Chapman was now sinking into alcoholism, and, as a consequence, getting increasingly erratic in both the quantity and quality of his contributions. Cleese put up with this for quite a long time, mainly because, while he was always the more productive of the two, Chapman seemed to possess a much surer sense of what material was likely to work best for a broad audience ('I trusted his judgement of this so implicitly', Cleese would say, 'that I never bothered to develop an idea that he didn't like'). Eventually, however, his patience began to wane.

They usually met each morning at Chapman's house, where Chapman somehow contrived to be the one who arrived late, and the drinking - of bottles of vodka, whisky and gin - preceded the writing. Within an hour or so, just as Cleese was warming up, Chapman was winding down. Cleese would stay seated at the typewriter, while Chapman wandered around the room, puffing on his pipe, contributing less and less, until, with lunchtime looming, he would look out the window at the nearest local pub and announce, 'Oooh, they're open!,' and that would be the end of his working day.

A further sign of how exasperatingly solipsistic Chapman could sometimes be was the fact that, while he was happy enough to leave his partner alone to write on behalf of both of them, it was another matter entirely when his partner worked solo for solo's sake. 'He was a bit cross', Cleese would tell me, 'when I put some money into a health club in 1970, and the guy who was going to run it died after six weeks. That meant that I had to earn some more money, quickly, so I did some Doctors In The House. And he was very disappointed that I did them on my own'.

Cleese, somewhat perversely, followed the writing partnership that had ended up like a bad marriage by starting a new one that grew out of an actual bad marriage. That is when he collaborated with Connie Booth.

It happened after he left the Pythons, and Chapman, to start a solo career. Still open, in spite of recent experiences, to the idea of sharing the creative process ('It makes me feel', he would later tell me, 'that I'm going to get somewhere that I wouldn't get on my own'), Cleese had already enjoyed writing with Booth when they collaborated on the delightful 40-minute movie short, Romance With A Double Bass - an adaptation of a story by Anton Chekhov - in 1974. That experience led to them exploring a number of other potential projects until finally they arrived at the idea of a sitcom: Fawlty Towers.

The problem was that, by this stage, their marriage was in serious trouble. There had already been a trial separation, with Cleese temporarily moving out of their house at Woodsford Square in Holland Park, and both of them had pondered the possibility of pursuing a divorce.

Ironically, however, the pair now found that, whenever they had reason to meet and talk about their respective ideas, the atmosphere was reassuringly amicable. An emotional weight seemed to have been lifted from their shoulders: they no longer lived so easily together, but now they could work together surprisingly well. It was a bitter-sweet discovery, but it offered a way forward that, professionally at least, was simply too propitious for either of them to resist.

They went ahead, therefore, and started collaborating on their sitcom. Once again sharing a home (although living in separate sections), they worked hard for a full six weeks on shaping each script, sitting side-by-side at a desk in an upstairs room, with Booth scribbling on a note pad and Cleese poised over a typewriter.

Their blend of strengths turned out to be similar to the one that Cleese had enjoyed with Chapman. 'I'm good at the carpentry', he would remark, 'saying, "let's shift that line up, move that section down a bit". I take a script along obvious lines, moving towards farce, but Connie stops me from doing the obvious'.

Their partnership went beyond even Galton & Simpson's in its forensic attention to detail. As a process it was a kind of comedic mastication, chewing over every line, reflecting on each ingredient, each trace of flavour, until they knew, completely, how and where best to place its taste. Add to that the additional editing that followed each recording - about forty minutes devoted to every minute of each half-hour show - and the degree of craft and care expended was simply unprecedented.

The pair would divorce in 1978 after completing the first series, but worked together again on the second one. Burnt out, for a while, by the intensity of the experience, they went their separate ways, as writers as well as people, after that celebrated show, but both remained proud of the fact that, out of such personal sadness, they had somehow managed to share such exceptional professional success.

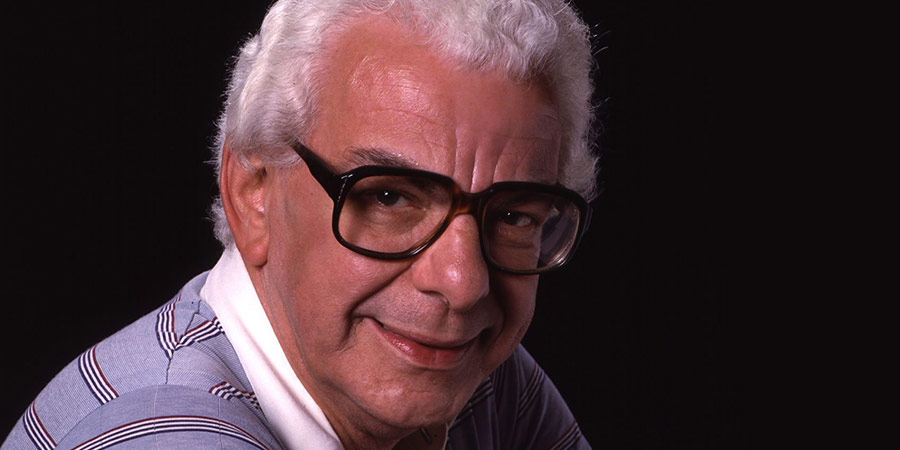

One other writer, meanwhile, was busy achieving the rare feat of thoroughly enjoying a writing career both on his own and in association with multiple colleagues. This was Barry Cryer, and, from the early Sixties until his death in 2022, he flitted quite contentedly between solo and shared projects.

He wrote perfectly well on his own, although, being such a gregarious character, he preferred the idea of a partnership. Cryer became, indeed, a serial partner-er: his creative companions included, at various times, both (but separately) Cleese and Chapman, as well as Peter Vincent, Willie Rushton, Ray Cameron, John Junkin, Graeme Garden, Tim Brooke-Taylor and Dick Vosburgh.

Cryer was actually a sort of writerly chameleon, able, very unusually, to rearrange his skill set to complement the peculiar talent of each particular partner. If the other needed someone to concentrate on construction, he could do that, and, in turn, if it was needed, he could be the one who wrote the gags, or did the monologues, or came up with the unexpected twists of wit.

Thanks to this versatility, along with his amiability, Barry Cryer became one of the few leading comedy writers who managed, throughout his long career, to navigate a sure and safe course between the Scylla of scarring solitude and the Charybdis of shared despair, which is one of the reasons why he was so much admired during his lifetime, and is so much missed now he's gone.

So what do all these separate snapshots of the comic writer's lot serve to tell us? The answer is: at least three things.

One is that, if you are brave enough to go it alone, you will require plenty of courage, discipline and self-belief, because you will need to be your own best critic as well as your own most loyal supporter. The best solo writers somehow manage to be better than the sum of their parts, even though all of those parts belong to the same soul.

Another point is that, if you are more inclined to enter into a partnership, neither forging a friendship nor fretting over the failure to do so is as anywhere near as important as complementing each other's distinctive talents. As far as partnerships are concerned, it is far better to be a good fit creatively than it is to be a comfortable one emotionally.

The other lesson, of course, is that none of these countless kinds or styles of contribution will flourish for long without being built on a bedrock of genuinely serious talent. Anyone, alone or alongside another, can put something down on paper, but it's another thing altogether to do so to a standard high enough to make those who perform it look really good, and make those who witness it really laugh.

Beyond all of this, the lesson for the rest of us, as the consumers of comedy, is surely to take more notice of, and show more respect for, the people who labour away, behind the scenes, to craft the material that gets others the laughs. The sheer strain it can take, to place the right words on each blank page, should never be underestimated, nor ever taken for granted.

In that suitably appreciative spirit, is always worth remembering the gentle jolt administered to Morecambe & Wise by Eddie Braben. It came in the middle of one week, when, burdened by one too many requests for further revisions, he sent them back a package containing forty blank pages, with a covering note that read:

'Fill these in - it's easy!'

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more