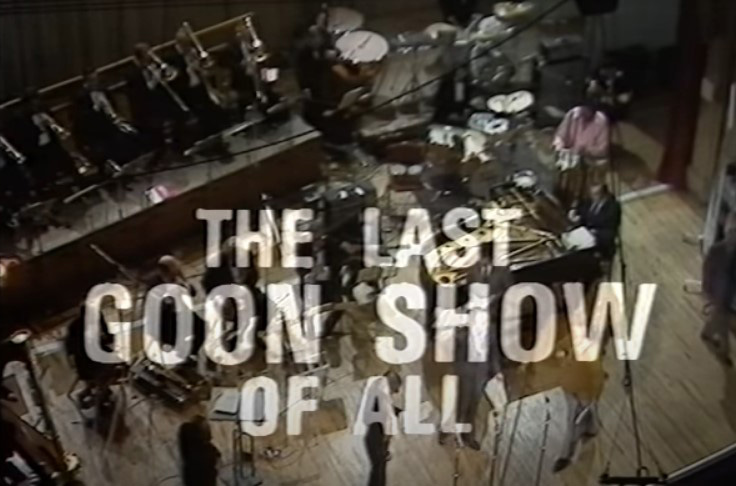

In search of lost time: Remembering The Last Goon Show Of All

The Last Goon Show Of All was recorded fifty years ago - twelve years after what was supposed to have been the last Goon Show of all. It seemed, at the time, a special but somewhat confused occasion, never quite sure what it was, why it was happening and what it was supposed to be doing, but, looking back at it from the vantage point of today, it seems to mark the start of a more general change in the way that we recall, and respond to, and try to retrieve the most precious aspects, and experiences, of our comedy past.

The past does not seem so much like a different country these days. It seems more like a sleepy village in Suffolk. We might have to negotiate our way through a few long and winding lanes, but we can travel there and back most weekends if we wish.

The phenomena of home recording, YouTube channels and commercial nostalgia releases - along with a belated but welcome change of attitude to the preservation of their own output by broadcasters - have combined to make cultural archivists of us all. We no longer need to rely purely on our memories to play back the shows of our youth; we can just slot in a disc, or click on a link, and watch them all over again whenever we want.

Something, however, is still missing. It is the thrill of the discovery, the intimacy of the experience, the first fine and full flush of fresh fandom. We know that we can never really get that back, and yet it is a craving that we can never quite let go.

We can binge-watch the box sets on an endless loop, we can talk about them (and argue about them) incessantly in online forums, and we can go full metal anorak and spend all of our free time fussing over every frame of the footage. What we cannot do, alas, is recover the moment, the real moment, which still matters so much.

This is why some of us, sometimes, get a bit too romantic for our own good. We just cannot, as Vic and Bob used to say, let it lie.

Without realising that what we really long to have back is not the show or the stars but the time that they and we used to share, we allow ourselves to be seduced by the idea of a reunion, a comeback, one last 'don't know where, don't know when' sunny day. It always results, for all but the most nostalgically-minded, as disappointing as the old boys' get together in Hancock's Half Hour ('I give you a toast: To absent friends - and may they stay that way!'), but still the craving remains.

Goon Show started it. It kept resisting, and then it relented.

From the early 1950s, Goon Show had been, without any doubt, the most innovative, imaginative and influential comedy show on British radio. Listened to by an audience of seven million or more, it gave a nation a whole community of characters (including Eccles, Bloodnock, Bluebottle, Henry Crun, Minnie Bannister, Neddy Seagoon, Little Jim and Grytpype-Thynne), and a tool cabinet of catchphrases ('You've dedded me'; 'Huuuullo, folks'; 'I don't like this game'; 'Everyone gotta be somewhere'; 'You can't get the string, you know'; 'He's fallen in the water!'). It had a generation talking in silly voices, and thinking irreverent thoughts.

It inspired such devotion that no one wanted it ever to end. No one, that is, except - every now and again - the Goons themselves. The pressure to keep progressing was starting to wear them all down. The ambition was still there, but now it was battling with anxiety and ambivalence.

As early as January 1959, Peter Sellers, shortly after signing a five-year movie deal with the Boulting Brothers, had expressed the belief that the latest (ninth) series of Goon Show was 'likely to be the last', but Spike Milligan, upon hearing this, had demurred, insisting that he had not 'made my mind up yet'. The notoriously mercurial Sellers then added to the air of uncertainty in the months that followed, claiming variously that he was 'finished' with comedy, ready to 'retire' from acting in favour of directing, and already considered himself an 'ex-Goon'.

In October of the same year, however, the BBC announced that Sellers would be returning alongside Milligan and Harry Secombe for a tenth series (consisting of six new episodes and seven repeats), starting on Christmas Eve and running for thirteen weeks. This would indeed turn out to be the last Goon series of all, but, rather than there being any formal confirmation of this fact, all of the fans of the show were left to speculate about its future.

Indeed, throughout the whole of the 1960s, the fate of the show would remain the subject of a strangely messy and slithering trail of conjecture, with the three almost/possibly ex-Goons resembling Laurel and Hardy in the scene from the movie Perfect Day, where, sitting outside their house in their over-stuffed car, they proceed to keep saying 'Goodbye' to a crowd of neighbours without ever quite setting off down the street.

In June 1961, for example, Spike Milligan was quoted as saying that he would 'like to pick up on Goon Show again', and, in a separate interview, Peter Sellers concurred, insisting that he 'would certainly like to get started on a new series', and that Harry Secombe had called him to commit to the same thing. This established a pattern in which their respective solo careers were interrupted intermittently either by expressions of reluctance to return or confessions of regret that they were not yet able to do so.

They did, in fact, get back together, briefly, on three separate occasions during the Sixties: once to supply the voices for the BBC's TV puppet show The Telegoons in 1963; again in 1966 to reprise an old twelve-minute sketch (edited from The Whistling Spy Enigma) for the ITV special Secombe And Friends; and then once again in 1968 to reprise an entire show (Tales Of Men's Shirts), as an odd exercise in 'filmed radio', again on ITV. As far as a proper new Goon Show radio series was concerned, however, any hopes were left hanging.

Spike Milligan, in 1967, called for the BBC to repeat all of the old shows, on the grounds that 'a new generation is dying to hear them', but he made no claims as to his willingness to write any new material for this new generation to consume. The broadcaster did, in fact, repeat a selection of shows every now and then during this period, including a well-publicised set of newly-restored episodes in 1970, but Milligan, like his two former colleagues, continued to pursue new solo projects and appeared disinclined to pick up where, together, they had left off.

Then, shortly into the new decade, came a major opportunity. The BBC's Golden Jubilee celebrations were due to begin in the autumn of 1972, and a wide range of events were being planned to mark the occasion. The Royal Mail was releasing a special set of stamps, archive exhibitions were being held both in London and various regional centres and the National Film Theatre was screening a special BBC TV season, along with a BBC-themed Royal Variety Performance, a gala concert at the Royal Albert Hall, a special float in the Lord Mayor's Show and even a society ball at the Dorchester.

The BBC itself, meanwhile, was planning numerous celebratory events and publications, which included four books and twelve commemorative albums, multiple radio and TV documentaries and 'historic' repeats, and a new recording of the first series of Dick Barton.

It was also hoped, privately, that this period of self-promotion could reach a peak with the much longed-for revival of Goon Show. The task of turning this dream into a reality was handed to the man who had overseen the last two series on the radio, John Browell.

The prospects of such a show actually happening, however, seemed slim at the start, because clearly nothing could go ahead without the participation of Spike Milligan, and Milligan, when Browell first contacted him, did not sound at all keen. Although he had always been vocal in wanting the old shows repeated, the notion of making a new show was quite another matter.

He felt torn. On the one hand, being proud and protective of the programme and the impact that it had made, he regarded this invitation from the BBC as a long-overdue recognition of its (and his) remarkable achievements, as well as the perfect springboard to promote the show to a whole new generation.

On the other hand, the thought of writing just one more high-profile script reminded him of all the pain and pressure that had come with shaping the original shows, and also challenged him, after more than a decade of doing other things, to recapture the old magic. An earlier attempt to do so, for the 1968 ITV special, had been aborted after Milligan, breaking under the strain, locked himself away in his office for several days, occasionally slipping notes under the door that simply read: 'I'm feeling ill. I can't write a thing'.

Weighing up the pros and cons, therefore, he decided to turn the offer down. Browell, nonetheless, knew Milligan well enough to refuse to take his decision as final.

Norma Farnes, Milligan's agent, would now prove a crucial advisor to Browell as he plotted his next move. Aware of how conflicted her client was about this matter, she wanted to ensure that the proposal at least remained on the table for long enough to allow him to reach a properly considered conclusion, but she was also eager to avoid the matter dragging on indefinitely, so she worked hard behind the scenes to brief Browell and the BBC as to how best to proceed.

She advised Browell, for example, that it was important to come up with one very specific recording date for the show - not a set of possible options, but a single non-negotiable date. The reason for this, she said, was that she knew how all three of the former Goons tended to react whenever any collective commitment was required.

Milligan might say, 'I'll probably do it if Pete does it'; Sellers would usually say, 'I'll probably do it if Spike does it'; while Secombe always said, 'I'll definitely do it if the other two do it' - but then their respective diaries would clash, none of them wanted to be the one forced to change any other commitment, and the whole thing would eventually collapse. 'Don't give them any choices,' she warned. 'Just tell them when it is.'

Browell thus chose 30th April 1972 as his non-negotiable date and, once he had worn down Milligan and got him to agree in principle to writing the script, he let all three know when the recording would need to be. This strategy appeared to work: Sellers and Secombe, attracted both by the prospect of a 'proper' reunion with fresh material, and also by the promise that it would be promoted as a truly special cultural event, were quick to clear a space in their schedules.

Milligan, however, still had certain conditions that he demanded the Corporation meet before he would agree to sit down and start to write. The list (which ranged from major matters such as the venue - it had to be their old haunt, the soon-to-be demolished Camden Theatre - to such knowingly trivial but nonetheless rigid requirements as to who was obliged to buy the brandy and milk for one of their traditional warm-up routines) was topped by the insistence that, along with the three Goons themselves (the return of the fourth original member Michael Bentine was, for Milligan, never an option), all of the old supporting cast must be involved.

Browell assumed, given how harmonious that team had mainly been, that this would be a reasonably easy task to achieve. The most recent announcer, Wallace Greenslade, had died back in 1961, but his predecessor, Andrew Timothy, was still available, as were the two regular musical contributors, Max Geldray and Ray Ellington.

The participation of Geldray, however, would prove a problem. Now based in Boston, Massachusetts, he was delighted to receive the request, but, when told that the BBC would not cover the price of his airfare, he announced that he was staying put.

The news infuriated Milligan and Sellers, who offered to pay for the ticket jointly out of their own fees. This embarrassed the broadcaster into backtracking and finding the sum itself.

The only absent friend now would be Wally Stott, who had arranged most of the Goon Show' music. He was in the process of transitioning into Angela Morley, and, in those less understanding times, felt too self-conscious to take part - a decision that was accepted, albeit with sadness, by the others.

This left one final issue for Browell to resolve. The BBC now revealed that it wanted to film the event 'for archive purposes'. Milligan, convinced (quite correctly as it would turn out) that those 'archive purposes' would end up being revised into 'broadcasting purposes', was adamant that it would not happen. 'The bastards won't keep their word,' he snapped at Norma Farnes. 'The answer is "No!"'

Farnes, once again, understood Milligan well enough to know that, a few months or years down the line, he might well end up raging about the BBC not filming the show, so she calmed him down and, assuring him that the cameras would be kept as unobtrusive as possible, managed to get him to change his mind. The project, at last, could progress.

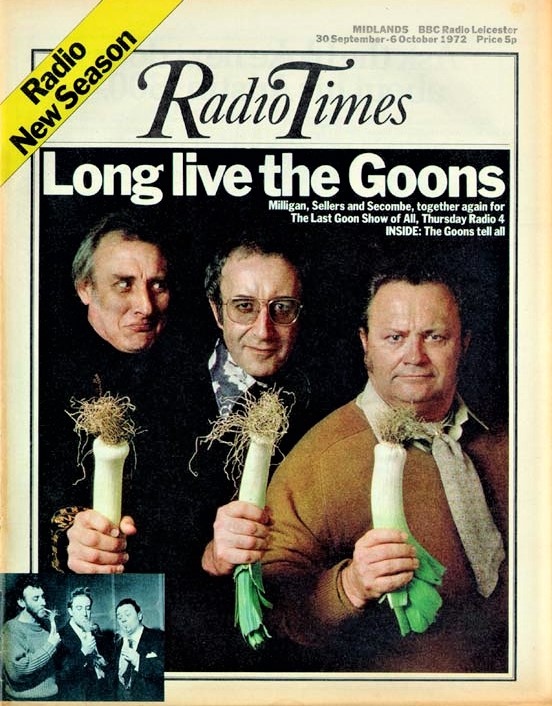

The reunion was thus announced to the media in March of 1972. It was said that Milligan, Sellers and Secombe would be getting back together at the Camden Theatre 'for a brief eight hours to rehearse, record and celebrate' the first proper new Goon Show in twelve years.

The hype started immediately. Peter Sellers, it was said, would be inviting 'Prince Philip, Princess Anne, Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon'. The nation's 'ordinary' fans were warned that, as the theatre could only accommodate five hundred people, they would probably have to pay 'black market prices' to have any chance of securing what were supposed to be 'free' tickets.

All of this gave the impression that, behind the scenes, everything was going well. The reality, however, was quite the opposite. Spike Milligan was still struggling to write the script.

Unsure as to whether to stick or twist, to produce a pastiche of his former style or a variation on his more current Q anti-format style, he kept bouncing back and forth between them like a trapped fly trying out all the windows. Scrapping one draft after another, as the days continued to go by, his mood was made only worse by the sense of anticipation that was starting to rise all around him.

Eventually, a mere six days before the date of the recording, a finished script arrived on the desk of John Browell. Unfortunately, after a quick read-through, it was deemed unusable.

There were many problems with it. The structure was loose even by Goon Show standards, the tone (and quality) was wildly erratic and - the most immediately troubling issue of all as far as Browell and his bosses were concerned - there were numerous irreverent references to royalty in general, and The Queen in particular, which, by the still rather stiff and stuffy standards of the time, were judged completely unacceptable for a broadcast programme.

What followed, as a consequence, was a stubborn stand-off between Milligan and Browell that continued right up to the day of the recording. Milligan, arguing that Goon Show had always been controversial, refused to revise one word of the script, while Browell, pointing out that broadcasters were now subject to far more formal and independently-administered strictures than ever before, and that several royal figures would be out there in the audience, kept begging him to relent.

On the morning of Sunday 30th April, therefore, it was still the case that no one was certain there was even going to be a recording that evening. The tickets had all been distributed, the VIPs were coming, the press were going to cover every aspect of the event - but there was just a great big black hole looming ahead of them all.

Everyone involved in the production, from the sound engineers and cameramen through to the musicians and sound effects operators, had no choice but to sit around and wait, as the minutes ticked by, and hope that something - anything - would be agreed in time for at least one brief and basic rehearsal.

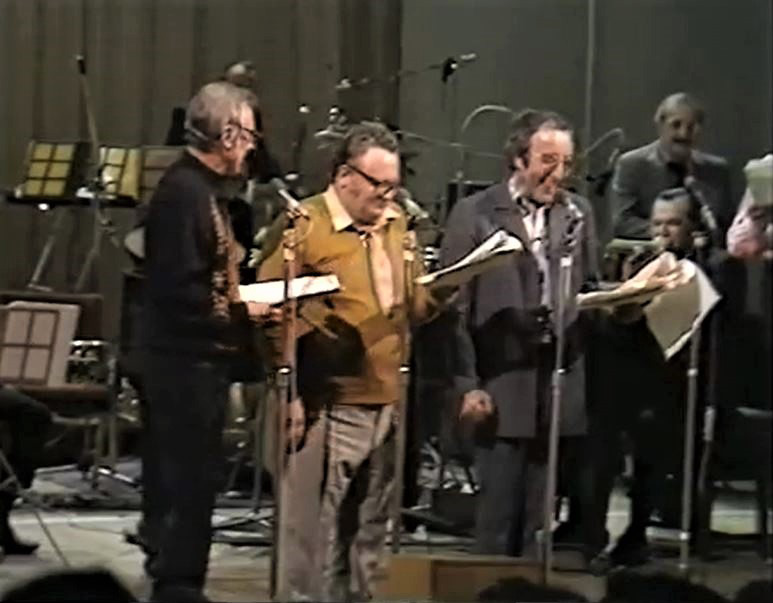

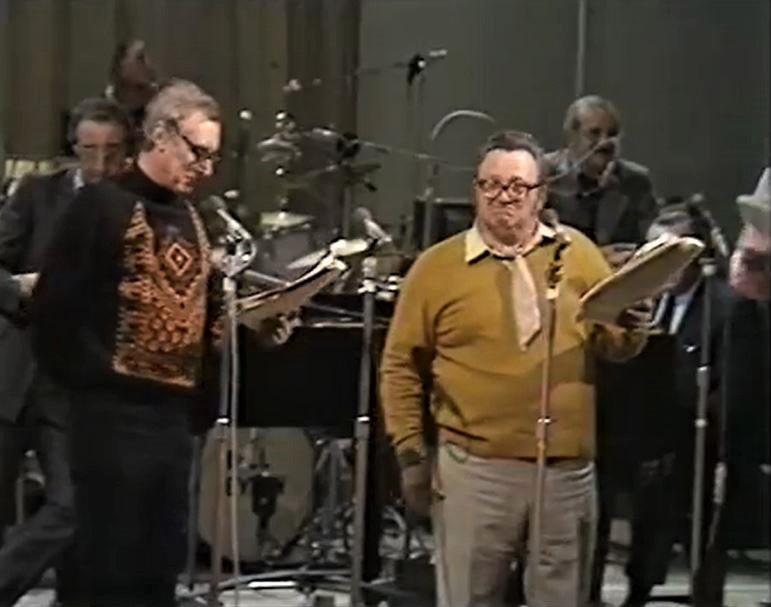

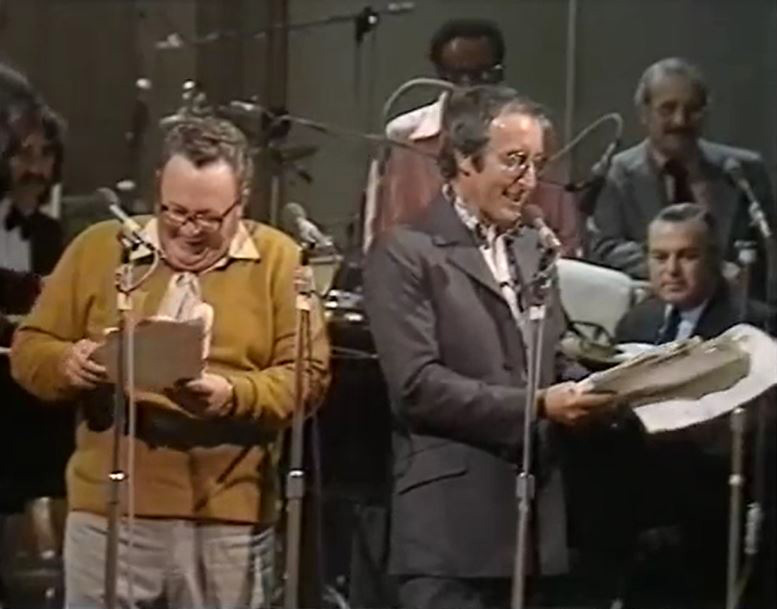

Eventually, by mid-morning, Sellers and Secombe, straining to keep their composure in spite of the cacophony of ringing phones and raging arguments that was echoing all around them, finally managed to persuade Milligan to sit down and work with them on some changes, and so, huddled around a rickety old trestle table in a shadowy corner of the theatre, the three Goons laboured away until they had something that looked and sounded vaguely like a Goon Show show. The rest, they accepted, would have to be reliant on whatever slivers of inspiration might get summoned up later that evening.

A greatly relieved Browell then raced off with the messy-looking and heavily annotated revisions so that they could be typed up into a formal script and copied for all the crew, and by the end of the afternoon it was finally acknowledged, with many massive sighs of relief, that they - just about - had something serviceable to record.

When the evening arrived, therefore, the contrast between the public and private scenes could hardly have been any starker. The audience, full of long-standing fans, was drifting into the theatre - noisy, emotional and highly excited. The team backstage, meanwhile, was struggling to shake off the tension of the past few anxious hours and find the energy suited to staging an enjoyable spectacle.

What ensued, once the lights went on and the occasion began, was a very strange, but very special, sort of mess. The deeply nostalgic audience seemed so grateful simply to be reunited with so cherished a part of their past that they were ready to embrace just about anything they were offered. The performers, on the other hand, were, at least to an unsentimental pair of eyes, jostled by conflicting emotions - anxiety, frustration, and brief but intense bursts of joyous playfulness, comic competitiveness and mutual affection.

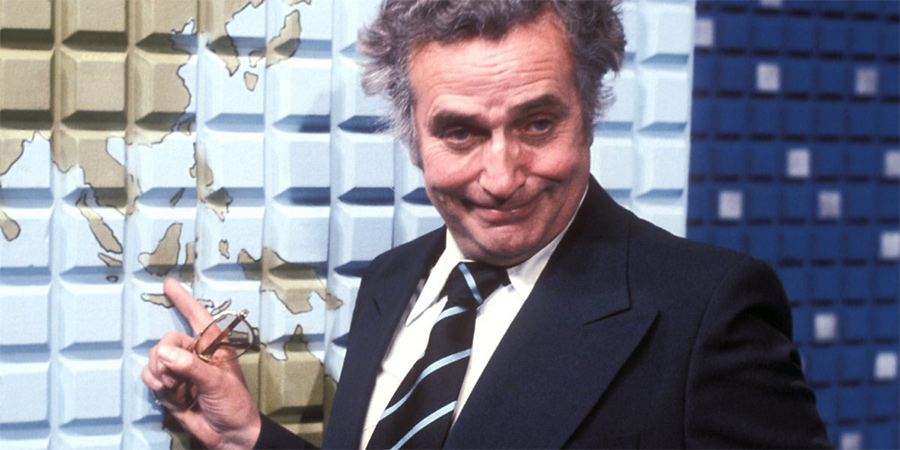

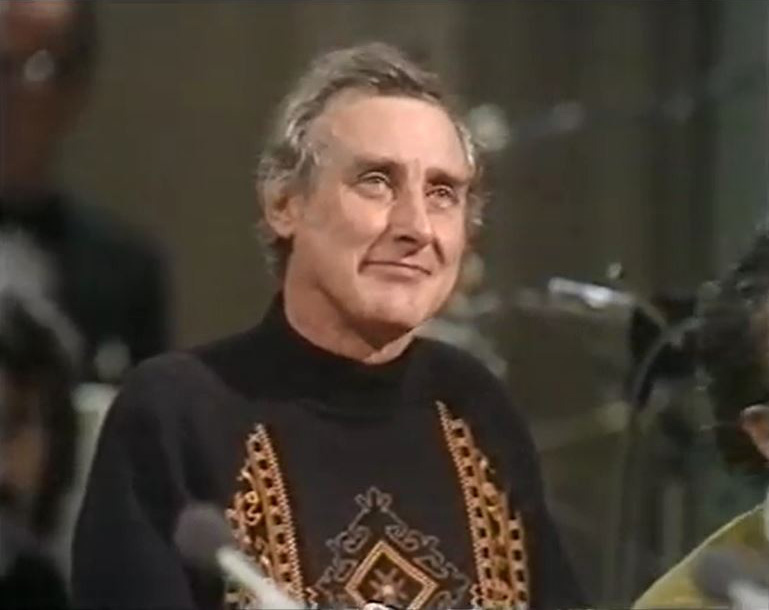

Milligan was the first to appear on stage, emerging from the shadows looking like a sleep-deprived student setting out for a final exam. Then Secombe arrived, seeming relaxed and ready for a convivial tea party, closely followed by a beaming Sellers, already waving cheerfully to all the rows of VIPs.

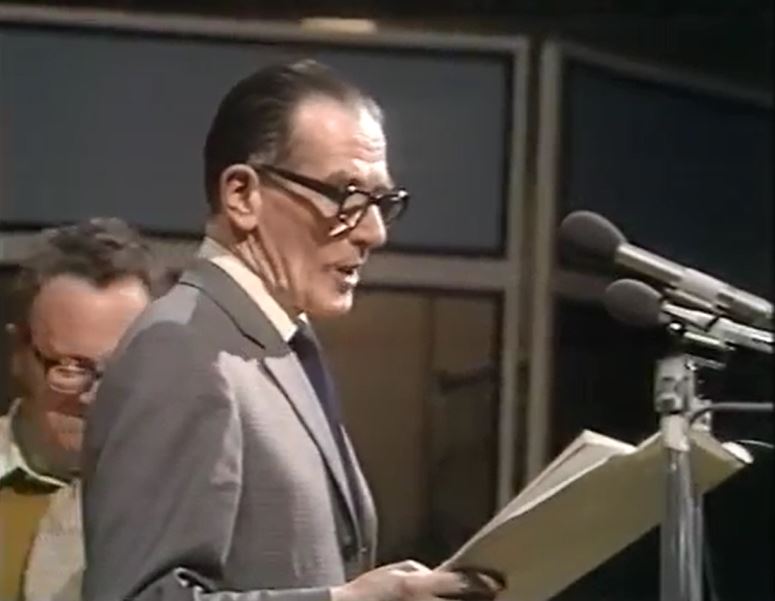

The three of them went through the motions of warming their audience, and themselves, up, and then the rather stern-looking Andrew Timothy strode on to the stage. 'We have had a large number of telegrams wishing us, believe it or not, good luck,' he announced glumly. 'And heaven only knows we need it.'

That arch-Goon Show fan Prince Charles, serving at the time with the Navy in the Mediterranean, had a message read out in his absence: 'As one of your most devoted fans I am enraged at the knowledge that I am missing your last performance. Last night my hair fell out, my knees dropped off and I turned green with envy at the thought of my father and sister being there.'

The show then began with Timothy setting the tone of self-conscious ambivalence towards the idea of a revival: 'This morning, BBC Archive delivered three coffins...'

The difference in demeanour between the three performers, as the action unfurled, was revealing. Milligan, throughout the show, rarely made eye contact with anyone, and seemed to oscillate between awkwardness and belligerence as he wandered in and out of the proceedings. Sellers, on the other hand, appeared chronically distracted by the sight of royal people in the audience, repeatedly waving, winking, nodding and grinning in their general direction. Secombe, meanwhile, was reassuringly professional, keeping things moving whilst exuding a sunny sense of contentment.

As far as the actual show was concerned, it soon became apparent, to those not lost in the reverie of the sentimental moment, that there was no real show at all. It was all warm-ups and warm-downs, false starts and digressions - three men, and multiple characters, in search of a storyline.

Milligan's script, in truth, was little more than a ragbag of old jokes (BLUEBOTTLE: 'You turn the knob on your side.' ECCLES: 'I don't have a knob on my side'), in-jokes (in relation to Sellers' car collection and Secombe's association with Harlech TV), jocular namechecks ('Here's a preview of next winter in Jimmy Grafton's attic'; 'Speak up, Henry - Eric Sykes is in'), and, deviating from the rather demure sauciness of the original shows, a few rather forced references to knee-tremblers, pot-smoking and foreplay.

The traditional thematic preoccupations of the show were still very much on display (plenty of World War Two references and mocking remarks about all kinds of regimentation), while a few perfunctory 'topical' allusions (to Edward 'The Grocer' Heath, for example, and Margaret Thatcher's 'incomprehensives') were slotted awkwardly into the mix. It was as if Milligan had typed the script with an old photo of the Goons positioned on his left and a recent copy of Private Eye propped up on the right, glancing back and forth at them as he tried to get the whole thing finished.

The best moments worked more like mini sketches rather than elements of some ongoing story, such as when Sellers, adopting his vaguely 'Michael Caine' voice, questions Secombe on why he seems to be impersonating The Queen:

SELLERS: What is your name, sir?

SECOMBE: Harry Secombe.

SELLERS: What a splendid memory you've got, sir. Now then, sir, would you like to explain as to why you are wearin' a flowered criton frock?

SECOMBE: Explain?

SELLERS: Yus.

SECOMBE: Haven't you read the court circular?

SELLERS: No, I'm waitin' till they make the film of the book of the sketch of the street of the play.

SECOMBE: Now listen, constable.

SELLERS: Yus?

SECOMBE: I am dressed like this because I have been asked to represent Her Majesty The Queen.

SELLERS: Oh, I'm sorry, Your Queen. My refund ferpologies, I'm sorry.

SECOMBE: It's too late for that.

SELLERS: It's only half past five.

SECOMBE: We're having difficulty starting this Goon Show.

SELLERS: Well, let's have a look in the tonk, then. Tonk? Ah, I see you've still got the same typist you 'ad in 1953.

SECOMBE: Yes, I still have her - no one's found out yet.

SELLERS: Yes, 'ere's the trouble, Your Queen. There's no jokes in this fuel tonk.

The show seemed at its most quaintly antiquated when it paused in order for the two musical interludes from Ray Ellington and Max Geldray to take place. In one way, of course, these moments were entirely apt, and very evocative of the original experience, but, in another way, they were awkward reminders of the one conservative element of an otherwise famously progressive comedy show, still clinging to the interruptions that other comedy shows of the time (such as Hancock's Half Hour) had already started to leave behind.

After one last warble of funny voices, the proceedings were eventually brought to an end by the sombre-faced Andrew Timothy, who announced: 'The next Goon Show will be on July the 7th 1982. And from Goon Show number 167: farewell'. After a brief pause, he added: 'P.S. Forever'.

Sellers and Secombe walked forwards, smiling and swaying to the play-out music, and let all the applause and cheers wash over them, while Milligan, as inscrutable as he was at the start, stood back, with a wistful semi-smile on his face, and surveyed the scene, still and silent, like some strange kind of ghostly presence. Then, while various family members joined the throng on stage, Milligan, his script still stuck to his sweaty hand, walked rather menacingly towards the audience, gestured for silence, and snarled: 'NOW GET OUT!!!'

One sensed that he half-meant it. It had been that kind of night - a night of half-meant gestures.

In the immediate aftermath, as the media crowded round, Milligan put on a brave front, telling reporters it had been a great triumph. 'Everyone loved it,' he said. 'Secombe's impression [of The Queen] was so good that Prince Philip fell in love with him. Didn't you see Princess Margaret take off all her clothes at the interval? They loved it.' A beaming Peter Sellers was more straightforwardly delighted, declaring, 'It was wonderful,' likening the experience to 'a strange dream, as though we had never parted'. Harry Secombe, unusually reserved for him, merely smiled and remarked, 'It was fine'.

In private, however, various degrees of disappointment were admitted. 'To be honest,' Secombe would come to reflect, 'it was by no means a vintage show, and the presence of Royalty out front lent a kind of reverence to what should have been an irreverent occasion.' Milligan merely admitted that it was not 'a particularly funny script', and then changed the subject. Andrew Timothy was the most forthright of all, saying that the script was 'very, very poor, very poor indeed'.

It would not be until the autumn, on Thursday 5th October at 8pm on Radio 4 (followed by the supposedly 'archive-only' film being shown on BBC One on Boxing Day), that the rest of the country got to hear a carefully-edited version of the show for themselves. Billed as 'one night of nostalgic, uproarious Goon-mania', it was received far more positively than many insiders had feared, mainly because so many fans had been waiting for so long for something - anything - to devour and enjoy. The context was kind to the comedy.

The reviewers tended to spend more time reflecting on the significance of the original shows, rather than on the reunion itself. They understood that it had been an event for the romantics rather than the realists.

'Are we ever going to see The Goons all together again for another series?' was a question one critic asked himself. His answer was that, seeing as all three of the participants had spent so many years making positive noises to that effect, it would have to be a possibility.

Then he asked the more interesting question: 'Would it be a good idea?' His answer to this was in the negative: 'I think this is a case of men who have moved on, developed and branched out in other fields, looking back, rather nostalgically, to their early days. Good days, but they have gone. [...] The Goons were a milestone, and I like to think of them as they were in the '50s.'

A record of the show was released a few days later, and sold quite well, and, at the very least, the renewed interest generated by the event provided an excellent base from which to launch a series of items (The Goon Show Scripts, followed by More Goon Show Scripts in 1973 and The Book Of The Goons in 1974) designed to promote and preserve the legacy. Whatever one thought of the comedic performance, it served a commercial purpose.

What is far more contentious is the wisdom of the numerous other reunions that have followed in its wake. Whereas the Goons, back in an era where merchandise was minimal and repeats were still fairly rare, probably needed a physical return to kick-start a major multi-media revival, this is no longer the case for those that have come after.

Old shows no longer need rescuing. The best-loved ones (along with quite a few mediocre ones) are often getting the commemorative book/box set treatment before they are even off the air, and, thanks to the more recent addition of streaming and other online services, they can live on and be enjoyed, in an ever-present past, without any real need for their creators to be coaxed back for one more performance.

This leaves the likes of Monty Python's hugely hyped, and hugely expensive, O2 reunion of 2014 looking even more dubious in its designs. Aside from the bitter-sweet spectacle of seeing the old stars struggle through the old material, there is surely also something sour about such events being priced beyond the pockets of many ordinary long-standing fans, and pandering instead, as a festival for fat cats, to the very kind of privileged cliques whom the old shows loved to mock.

If these underwhelming events teach us anything at all, it is arguably just this: be careful for what you wish. When The Goons came together again, twelve years on, their presence suggested to all comedy fans that if you crave it they will come.

What we really crave, however, cannot be satisfied, no matter how expensive and exclusive the access-all-areas ticket we may have claimed. To summarise Proust, as the Pythons so famously failed to do: all that we can ever recover of what is precious in our past is through what we already have, stored away for free, in our own hearts and minds.

So let's not dig up any more of these old heroes, expecting all their later years to fall away like specks of soil. Let's leave them be, with gratitude and respect, and, like with those crumbs of the madeleine soaked in Marcel's lime-blossom tea, content ourselves with whatever memories, for each of us, may still spring back into being.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreThe Last Goon Show Of All

Recorded to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the BBC, Spike Milligan, Peter Sellers and Harry Secombe performed the 161st and (what is intended to be) the last ever episode of The Goon Show.

Also featuring the show's original music acts Max Geldray and the Ray Ellington Quartet, and the show's original announcer Andrew Timothy.

First released: Sunday 5th October 1997

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Tapes: 1

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Goons - Unchained Melodies - The Complete Recordings 1955-1978

The Goons Unchained Melodies - The Complete Recordings 1955-1978 is a 14-track picture CD album featuring all of the of The Goons' studio recordings between 1955 and 1978, including the two EMI singles Unchained Melody / Dance With Me Harry from 1955 and You Gotta Go Oww! / My September Love from 1956 plus all 6 Decca singles from 1956 through to 1978 including The Ying Tong Song & I'm Walking Backwards For Christmas.

Picture sleeve booklet containing extensive sleeve notes written by Mark Powell.

First released: Monday 1st January 2007

- Released: Monday 23rd July 2007

- Minutes: 46

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: Decca

- Minutes: 46

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Goon Show Scripts

Written and chosen by Spike Milligan, this is a collection of some of the very best scripts from the landmark radio sensation, Goon Show.

The book also includes drawings by Milligan, Harry Secombe and Peter Sellers.

First published: Thursday 19th October 1972

- Publisher: The Woburn Press

- Pages: 191

- Catalogue: 9780713000764

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

More Goon Show Scripts

A second collection of scripts for the very best episodes of Goon Show, picked by writer Spike Milligan.

This volume includes a foreword written by Goon Show superfan, His Royal Highness Prince Charles, The Prince Of Wales.

First published: Thursday 8th November 1973

- Publisher: The Woburn Press

- Pages: 151

- Catalogue: 9780701804084

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Book Of The Goons

A further compilation of Goon Show scripts, writings and drawings.

First published: Tuesday 1st January 1974

- Publisher: Robson Books

- Catalogue: 9780903895262

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Goons: The Story

Goon Show first went on air at the BBC as Crazy People on 28th May 1951. There then began a terrible rasping, squealing, giggling, snorting period of lunacy which continued unabated until 1960. Fifty years after the first show there is still a huge interest in The Goons, with each new generation discovering afresh the anarchic humour that has had such a huge influence on so many of today's top comedy performers.

This fascination collection of reminiscences, photographs and sketches is the definitive story of Eccles, Bluebottle, Neddy, Bloodnok, Grytpype-Thynne, Moriarty, Minnie Bannister, Henry Crun et al from those who know them best.

Under the patient guidance of Spike's long-term manager, Norma Farnes, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe, along with a select handful of friends including Eric Sykes, delve into their dusty old memories to help piece together the history of The Goons.

First published: Thursday 6th November 1997

- Published: Thursday 7th June 2001

- Publisher: Virgin

- Pages: 224

- Catalogue: 9780753505298

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Virgin

- Pages: 192

- Catalogue: 9781852276799

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.