Ill-advised revivals: The sitcom's living dead

There is only one thing worse than a sitcom that has outstayed its welcome, and that is a sitcom that has not only outstayed its welcome, but also outstayed some, or most, or even all, of its original cast. It is happening increasingly often.

Even the best sitcoms seem to go out with a bang these days only to limp back with a whimper. The name might be the same, the look might be almost the same, but the key ingredients have been changed and cheapened, without any apparent concern for artistic integrity or critical tastes: the only thing that matters to broadcasters, it seems, is the 'brand', and the brand must play on.

It is, alas, by no means a recent phenomenon: the past few decades of British comedy are littered with ignoble instances of writers and producers attempting to find new ways to keep a current sitcom going, or, when the sitcom in question is dead and buried, to dig it up again and drag it back, kicking and screaming, to the TV screen.

What these acts of sitcom recidivism reveal is how differently actors are viewed and valued by the producers and the public. To the public, the leading actors in a sitcom tend to be regarded as an essential part of its authenticity and appeal, but to the producers, they seem to be regarded as the most replaceable of the show's working parts.

It comes down to ideas about authorship. In the minds of most producers, the authorship of a sitcom is simply down to the creators and - unless it's a US-style team enterprise - the writers. Most British producers would balk at the prospect of reviving or revising a popular sitcom without first seeking and securing the input (or at least the imprimatur) of the writers who did so much to help shape its original success. Aside from the likelihood of there being legal rights involved, there is also a very traditional assumption that it is the writers, and the writers alone, whose signature is stamped on a sitcom.

This, however, is at best a simplification and at worst a blatant misconception. In the modern sitcom, the truth is that all of its greatest characters owe their existence to two, rather than one, types of author - the actor as well as the writer. While the latter might well insist that it was they and they alone who thought and dreamed and clicked away at the keyboard to bring a character to life, the reality is that it is only with the added wit, skill and imagination, and indeed the flesh, bones and sheer believability, of the actor, captured on the screen, that the character truly lives and breathes.

Week after week, year after a year, in one series after another, the union grows ever more organic and symbiotic, as the writer adapts the character to suit the actor, and the actor brings more of the character to his or her self, and the collaboration continues. This is what the screen does to actors and their characters: it captures and fuses them together forever, securing the sine qua non. One cannot replicate it, let alone derive from it and develop it, without diminishing it.

Sitcom characterisation has, indeed, always been a collaborative exercise, and when that collaboration at its heart ceases to be respected, by either side, things will start to fall apart.

There are, in particular, a trio of notable cases to be discussed here - Potter, The Legacy Of Reginald Perrin and Yes, Prime Minister - where the writers and makers of sitcoms failed to learn the lesson that the actor who plays the central character, or even the ones who make up the broader cast, are simply not as expendable or interchangeable as they are as a matter of routine in an evanescent play on the stage.

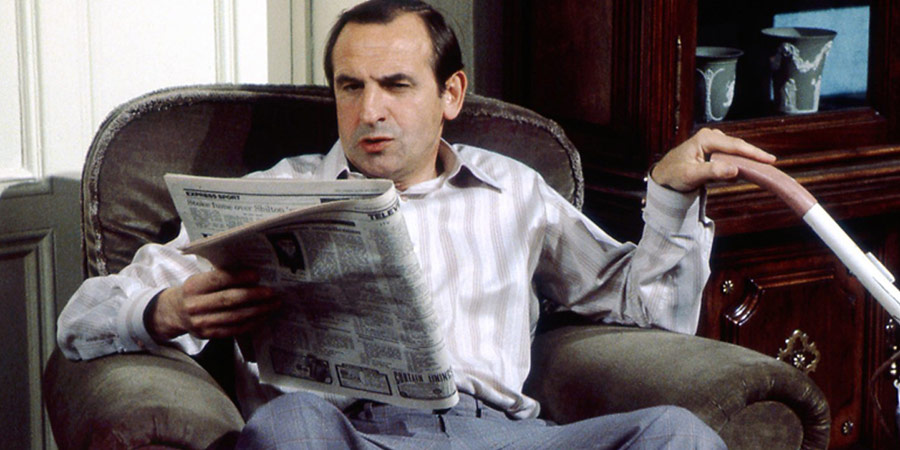

An example of the first level of error - re-casting the central role - can be found in 1982, when the BBC was planning to make a third series of Roy Clarke's very popular sitcom Potter. Starring Arthur Lowe as retired captain of industry-turned-chronic busybody Redvers Potter (by far his best role since Mainwaring in Dad's Army), with Noel Dyson as his put-upon wife, Aileen; John Barron as his like-minded vicar friend; John Warner as 'Tolly' Tolliver, his weak-willed next-door neighbour; Honor Shepherd as Tolly's independently-minded wife, Diana; and, among others, Harry H. Corbett as a social-climbing ex-gangster named Harry Tooms, the reaction to past episodes had been excellent, and there was a clear appetite for more.

Part of its appeal could be found in its satirical treatment of the prevalent male chauvinism of the time, with the vicar strolling idly around the grounds of his church apparently oblivious to the sight of his wife, usually attached to an over-loaded wheelbarrow, struggling with the most onerous tasks of manual labour, and Potter sitting about at home offering 'helpful' critiques of his own poor wife's efforts at plumbing, engineering, electrical repairs, carpentry, sundry use of pliers, screwdrivers and hammers, and basic domestic maintenance and organisation ('Look, Aileen,' he says to her tetchily at one point when she dares to ask a question, 'will you just get on with mending the bed, please?').

Another aspect that audiences embraced were the rambling conversations that the two men frequently had, which came with the comical contrast between their own worldly-wise self-images and the foolish insularity of their actual thoughts, sounding rather like, in its own modest way, an English suburban version of Waiting For Godot's Vladimir and Estragon stuck in a sitcom:

POTTER: We must continue to help Tolly.

VICAR: Mmmm?

POTTER: Yes. Give him aid and comfort almost daily.

VICAR: Well, don't we?

POTTER: Needs more.

VICAR: More?

POTTER: Yes, poor devil.

VICAR: He's not dying or anything, is he?

POTTER: No. Of course he's not dying!

VICAR: Ooh, I am relieved to hear that. I've got all the funerals I can handle.

POTTER: It's Diana.

VICAR: She's dying?

POTTER: Is she? I hadn't heard that.

VICAR: You just said so

POTTER: No I didn't! You just said so!

VICAR: Only because someone told me.

POTTER: Who?

VICAR: You!

POTTER: They're not dying!

VICAR: Neither of them?

POTTER: Neither of them.

VICAR: Thank God for that. I didn't know they'd been ill.

POTTER: They've not been ill!

VICAR: Mark you, it's always the vicar who's the last one to hear.

POTTER: I'm not surprised. You don't listen.

VICAR: What?

POTTER: See what I mean? You don't listen!

VICAR: Well, of course I listen!

POTTER: What?

VICAR: Why do you say I don't listen?

POTTER: What d'you say?

VICAR: Listen!

POTTER: Someone coming?

VICAR: Are they?

POTTER: Yes. If it's anyone, it's probably...er...er...

VICAR: Who?

POTTER: ...It's on the tip of my tongue...

VICAR: I can't hear anything.

POTTER: ...Shan't rest now until I remember what that was...

VICAR: Probably a false alarm.

POTTER: The thing is, we must help Tolly with Diana.

VICAR: They seem very close.

POTTER: Oh, he dotes on her. Dotes on her!

VICAR: Mmm.

POTTER: I mean, you hear of these cases, but the full horror of them doesn't strike you until it's happening under your nose.

VICAR: Yes, yes. He spoils her badly.

POTTER: Well, I wouldn't say 'badly'. I think he's made a first-class job of it....AILEEN!

VICAR: What???

POTTER: That was the name!

VICAR: What name?

POTTER: On the tip of my tongue!

The combination of Roy Clarke's artfully droll writing and Arthur Lowe's still-peerless pauses, slow-burn reactions and quizzical expressions, as well as John Barron's always sharply attentive support, made these exchanges a regular delight. A third series of such wryly amusing dialogues and performances could not, for many viewers, come soon enough.

Then tragedy struck, not once but twice in quick succession: in March 1982, Harry H. Corbett died suddenly from a heart attack; and then in April, equally unexpectedly, Arthur Lowe passed away from a stroke.

Many might have assumed that, after the loss of not only your star but also the most famous member of your supporting cast, you would reluctantly but wisely declare that your sitcom has died along with them, but, in the case of Potter, this did not actually happen. The BBC, apparently unable to discard a ratings winner even in this wretched situation, instructed Clarke to continue writing the next series as best as he could.

The result was that, when Potter duly returned early in 1983, Corbett's character, without any explanation, had simply disappeared without a trace, while Redvers Potter was still there, sitting up in bed as usual next to Noel Dyson, only now he was played by Robin Bailey. Even though this Potter was tall and angular, whereas the previous Potter was short and round, and this Potter sounded decidedly posher and surer of himself than his predecessor, all of the old familiar characters responded to him as though nothing whatsoever had changed, and the opening episode went on as normal.

Bailey was good - he was himself a very clever and crafty actor - but his presence never stopped being seen as a negative: he was 'not Arthur Lowe'. He stuck out in every scene as if someone had clumsily Photoshopped his image into someone else's picture. In a revival of a self-contained play, after an appropriately long gap, his portrayal might have worked, but in an ongoing sitcom, where the previous actor's interpretation had already become part of the character's essence, it never had a chance. People don't look at a script, they stare at the screen, and the screen was now missing something vital.

Understandably confused and bemused, the viewers soon started drifting away, and the series limped on to a lonely end. The sitcom then faded swiftly from the screen, and from memory, when, if only it had been allowed to bow out with dignity one series earlier, it could have been remembered fondly for its short but well-crafted run.

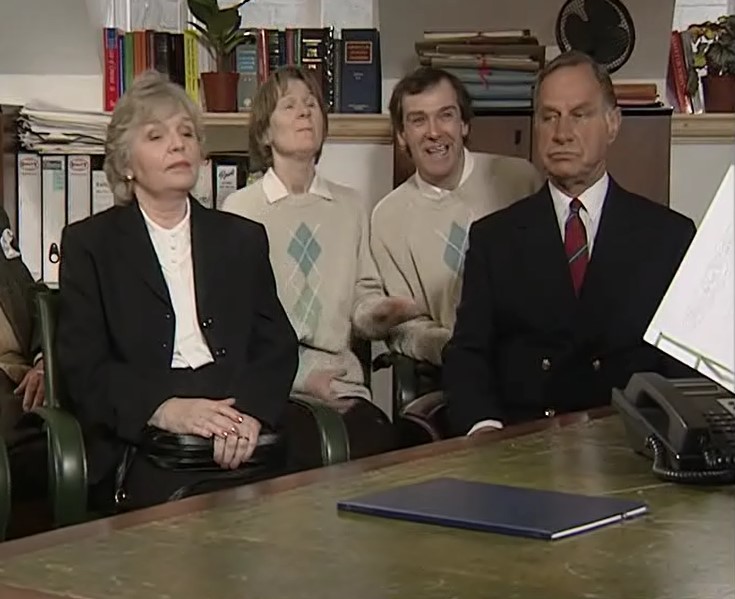

The same is true, but even more so, when we move on up to the second level of error - the bid to bring back a sitcom without any of its central stars. The folly of this exercise in reconditioned nostalgia was apparent more or less immediately to many of those who viewed the revival of Yes, Prime Minister in 2013, which arrived twelve years after the death of Sir Nigel Hawthorne, and eighteen after the passing of Paul Eddington.

The sitcom had actually first returned in 2010 as a stage play by its original writers, Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of their show's screen debut. The relative success of that supposedly one-off venture led to them deciding, in an uncharacteristically rash moment, to make another series for television.

The two writers, once again displaying the hubris of quill-penned dramatists leaning out of the window and whistling up yet another handy Hamlet, disregarded the fact that the characters of Hacker and Sir Humphrey, in the eyes and minds of the audience, would always be inextricably intertwined with the actors Paul Eddington and Nigel Hawthorne (as, arguably, was the character of Bernard Woolley with the actor Derek Fowlds), pushed ahead with the project, reasoning that, while Eddington and Hawthorne were much-missed, the sitcom had been their creation, with their words and ideas, so there was no insurmountable reason why they should not bring it back with other actors playing the roles that they wrote.

'I realised,' said Lynn, 'that so many beloved characters have been recast, like Doctor Who, James Bond, Sherlock Holmes - not to mention Hamlet! - and the audience simply accepts a new interpretation by a different actor and treats it on its merits. We hoped that would be the case with our characters.'

Even the BBC, on this occasion, baulked at the proposal to re-cast such a classic sitcom (it did ask to see a pilot script, but the writers, angry at what they took as a lack of trust and sufficient respect, turned them down), but Jay and Lynn eventually found a broadcaster in the form of the cable and satellite channel GOLD. David Haig (as Jim Hacker) and Henry Goodman (as Sir Humphrey) agreed to resume their stage roles, while Chris Larkin was recruited to play Bernard Woolley, and Zoe Telford was brought in to play the new character of special advisor Claire Hutton.

The first episode, entitled, Crisis At The Summit, was broadcast in January 2013. Featuring a credit sequence that used a new set of caricatures by Gerald Scarfe and an upbeat re-recording of Ronnie Hazlehurst's original theme tune, it was basically an updated version of the first act of the play (Europe is in financial meltdown; Britain's Government clings precariously to power after a close election; the Cabinet is divided; and the Prime Minister is in urgent need of help from dubious new allies), introducing the initial elements of the ongoing plot and as well as establishing the newly-cast characters.

Set in Chequers over the course of an autumn weekend, the rest of the series saw Hacker and Sir Humphrey embroiled in a power struggle that involved such topics as MPs' expenses claims, secrecy, leaks, patronage, Scottish independence, post-colonial diplomacy, the huge debt crisis, the influence of oil-rich countries, the purpose and influence of the BBC and the debate concerning global warming. The over-familiarity of these themes, of course, was more the fault of politics than the sitcom, but it did not help make the revival seem fresh.

The acting was also uneven. The most successful of the performances was from David Haig as Hacker. A tightly-coiled ball of nervy frustration, suggesting a dollop of Harold Wilson, a big drip of John Major and a wee dram of Gordon Brown, he was instantly believable as a Prime Minister weighed down by the woes of the nation whilst worried about the intrigues and schemes that are creeping about within his party. Never able to entirely ignore the nagging feeling that he is not up to a job whose crucial description is still missing, there was a delicate sense of pathos about him that added to the air of authenticity.

Less successful was Henry Goodman as Sir Humphrey, mugging almost as much as he had done in the stage play. In stark contrast to Nigel Hawthorne's portrayal, whose calm visage usually allowed only the subtlest hint at the synaptic acrobatics that were going on behind the bland mandarin's mask, Goodman's characterisation was all show and tell, with squat-thrusting eyebrows, darting eyes and a ready grin that suggested he was more Tigger than Jeeves, more Uriah Heep than Iago, and certainly not the discreetly dangerous, panther-like plotter of the original series.

Chris Larkin's Woolley also lacked the unforced charm and well-schooled dutifulness of Derek Fowlds's interpretation, although his sleepy-haired naivety, if writ a little too large, did at least suit the comedy of his character as it was now written. Zoe Telford, on the other hand, struck a sure tone from the beginning as the driven and doubt-free Dominic Cummings of her day, Claire Hutton.

What was most reassuringly impressive about the series were the scripts, which were full of Jay and Lynn's trademark rigour and wit. They were topical (WOOLLEY: 'A Hung Parliament's a bad thing?' SIR HUMPHREY: 'Yes, Bernard. Hanging's too good for them!'); amusingly nerdish ('No Prime Minister or US President has been elected without a full head of hair since Eisenhower and Churchill in the 1950s'); and admirably candid (SIR HUMPHREY: 'We will have to pay a premium on the loan, but not for many years to come, when there will be a different government.' HACKER: 'Well, that's all right, then!'); and provided viewers with the main reason for staying with the sitcom and watching the whole of the run.

The critical reaction to the revival, however, was, to put it generously, mixed. Among the reviews, The Independent's Tom Sutcliffe felt that the pace of the comedy 'was a beat or two off'; the Daily Telegraph's Mark Monahan was much more enthusiastic, claiming that the 'writing is as sharp as ever'; while Sam Wollaston, writing in The Guardian, delivered the most damning of all the responses, branding the decision to bring back the show 'a mistake' before adding: 'Best forgotten, lest it sully fond memories'.

The audience figures, on the other hand, were unambiguously dispiriting. The first episode was watched by an estimated 283,000 people (which amounted to approximately 1.17% of the available audience). It easily beat the channel's twelve month 'slot average' of 114,000 viewers (about 0.47% of the available audience), but it was a poor reward for a sitcom that had always worked so hard to engage with the biggest and broadest audience possible.

The viewing figures remained tiny throughout the rest of the series, ranging from an initial peak of 306,000 down to a mere 109,000 for the sixth and final episode; averaging just 202,000 per show. It was still a coup for GOLD, which boosted its performance in that time slot quite significantly, but, for a sitcom of such stature, and with such a history, it really did not seem right.

It went out as meekly and swiftly as a sacked junior minister, without any noticeable press coverage or even much discussion on social media. For all the optimistic talk of the multiple players of Doctor Who, James Bond, Sherlock Holmes and Hamlet, the lack of enthusiasm for the revival of Hacker and Sir Humphrey told its own truth. The reality was that, beyond the paper description of Yes, Prime Minister, its living reality would always remain, locked on the screen, with Paul Eddington, Nigel Hawthorne and Derek Fowlds.

This, however, was far from being as bad as it gets as far as resuscitated sitcoms are concerned. While the return of Potter and Yes, Prime Minister seemed more than a little injudicious, an example from the third level of error - going on without anyone at all in the central role - underlines just how much more recklessly irrational things can get.

In 1996, the BBC unveiled a decidedly unexpected new sitcom: The Legacy Of Reginald Perrin. It was unexpected for two reasons: it had been seventeen years since its 'prequel', the extremely successful The Fall And Rise Of Reginald Perrin, had last been on the screens; and twelve years since its star, Leonard Rossiter, had died.

The original writer, David Nobbs, was still alive, and this new series had been adapted by him from his own novel of the same name (published the previous year), but it still seemed a strange move to revive memories of such a hugely-popular show only to risk tarnishing them with such a belated and bemusing-sounding sequel. It was not the only sitcom 'brand' that was being revived that year by the BBC - amongst others, it had commissioned Carla Lane to write another series of The Liver Birds (after its own seventeen-year hiatus) - but it was the only one that was coming back without the actor who had excelled in the starring part.

There was an ominous precedent for this kind of 'post-history' of a memorable comedy character: after the death of Peter Sellers in 1980, whose portrayal of the incompetent Inspector Clouseau had been one of the comic highlights of the past two decades, director Blake Edwards (who had always resented the star's popularity undermining his claim to be the proper 'auteur' of the series) decided first to shake out all the dregs from the bottle by using old outtakes and deleted scenes, stitched together with freshly-filmed footage, to make a 'new' Inspector Clouseau movie, Trail Of The Pink Panther (1982), and then, relying on the conceit that the character had undergone plastic surgery and subsequently disappeared, he hurriedly made another one, Curse Of The Pink Panther (1983). Both movies not only flopped at the box office, but also attracted considerable criticism for the mixture of bad taste, greed and laziness that had led to the 'misguided and macabre' exploitation of the deceased Sellers' image and achievements. The Legacy Of Reginald Perrin, in the absence of Leonard Rossiter, now seemed open to a similar set of complaints.

The first thing that was wrong about it, aside from the question of taste, was that the premise was so shamelessly derivative. In the 1951 British movie Laughter In Paradise (written by Jack Davies and Michael Pertwee and starring Alastair Sim), an eccentric man leaves a fortune on his death to be divided equally between several people - on the condition that they complete one task each that is totally contrary to their respective natures. In The Legacy Of Reginald Perrin, an eccentric man leaves a fortune on his death to be divided equally between several people - on the condition that they complete one task each 'that is totally and utterly absurd' and contrary to their respective natures.

There are homages and there are rip-offs. This was a rip-off.

The other thing that was wrong about it was the fact that The Legacy Of Reginald Perrin did not have Reginald Perrin, or, more to the point, Leonard Rossiter, in it. To take a sitcom that owed so much of its success to its central character and star, and then adapt it so that it becomes a kind of constant meditation on the absence of that central character and star, was never likely to work. Like a solar system without its sun, it was just a dim idea.

Its best chance of success would have been to have attracted a largely new audience, ignorant about the sitcom it was succeeding and therefore unconcerned by what was now missing - except that, unless its audience already knew each character's backstory and cared more than a little about their fate, there was nothing much there to attract them in the first place. No show could be entirely unwatchable when it boasted two such powerfully artful comedy actors as Geoffrey Palmer (as the aimless ex-army man Jimmy) and John Barron (as the axiom-mangling ex-boss CJ), but most of the other characters, who had originally been designed to be little more than stooges to Perrin himself, lacked the substance and comic definition to command much interest.

The consequence was that, once the show suddenly deviated slightly from the Laughter In Paradise template and followed the figures as they resolved to pursue a communal approach to their obligatory 'absurd' goal, it seemed too much like so many stock sitcom characters in search of a coherent narrative. The final few episodes, which were supposed to build in dramatic momentum as the group plotted to take Westminster by storm with their anti-ageism campaign, actually lacked the conviction to take the plot seriously, and settled instead for numerous digressions and detours to allow all the characters more time to wander about repeating their old catchphrases while generally looking confused.

There were just far too many cock-ups on the revival front, such as Perrin's widow (played by the able but here under-used Pauline Yates) having to provide a long-winded exposition of the basic plot, for the benefit of any viewers coming late to the sitcom at the start of the second episode, and then linking the subsequent scenes, by telling it all to her suspiciously dazed-looking cat; then, in a couple of the many ill-judged stabs at hilarity, David ('Super!') Harris-Jones and his wife Prue popped up dressed respectively as Long John Silver and Nell Gwynn only to go straight back home again, and Harris-Jones later decided to join Reggie's insipid son-in-law Tom ('I'm not really a campaign person') Patterson on a spying expedition that saw both of them donning (for no obvious reason) joke shop ginger wigs, beards and kilts for the occasion; there was also a small battalion of elderly cloth-capped gents with walking sticks, straight out of central casting, who were sent marching across a field like some awful am-dram tribute to Benny Hill; there were also several, increasingly tiresome, romantic sub-plots, none of which were remotely convincing; and a hopelessly awkward scene set in the BBC's own studios, which featured the forcible abduction of the newsreader Angela Rippon followed by an impromptu address to the nation by a suddenly coherent Jimmy.

None of this was helped by the decision (almost always unwise) to release the composer Ronnie Hazlehurst from conventional theme tune confinement and send him out into the wild, where he was left to roam free through just about each and every scene, marking his territory with the most irritatingly intrusive effusion of droning trumpets and trombones, fluttering flutes and rib-rattling glockenspiel sounds, often with absolutely no connection to the comedy. True, his distinctive brand of cloying sitcom muzak (which most notably came to seep-through the walls of Last Of The Summer Wine like serious water damage) had also figured in the original Perrin series, but there, mercifully, it had been kept comparatively restrained; here, unfortunately, it was mercilessly overblown and out of control, the aural equivalent of a sharp elbow repeatedly stabbing into the side to remind the viewer when he or she should find something funny, daft, sweet or startling.

That was the saddest thing about The Legacy: it seemed to know how strained the whole thing was. Each time the cast gathered together to share a scene, even they seemed to be staring at the space where Perrin ought to have been, as if they were the first people pondering the hole in a Polo. Even David Nobbs's trademark witty lines too often here sounded forced and obvious, such as the former City trader who complains that 'there's no future in Futures'.

Critics, on the whole, were not kind. One, who summed up the show as 'an ill- conceived sequel' featuring 'a group of old catchphrases', complained: 'What's really depressing about this enterprise, apart from the unprovoked abuse of a long-dead horse, is the desperate crudeness of its engineering'; another remarked that, 'without Leonard Rossiter, the effect was that of a wedding where the bridegroom fails to show'; another, echoing this point, lamented the fact that, without the presence of Perrin himself, the remaining characters 'all just sit around like some heritage group, spouting half-remembered catchphrases at each other'; while another simply dismissed it as 'dreadful'.

The final episode in the series clearly left open the possibility of a second set of episodes, or even multiple more series, being commissioned, but, by the time that it was actually screened, the negative reaction had ensured that this was not going to happen. David Nobbs (who would later be involved in an even more blatantly otiose remake of The Fall And Rise, renamed Reggie Perrin, in 2009) had said that the point of the new sitcom was to highlight 'the large number of old people in our society and about redundancy and insecurity in the workplace'. It was a pity that, if this really was his motivating theme, he did not choose to explore it via a completely new fiction, rather than attempt to impose it on an old, and over-familiar, one that had been about something else.

One would have thought that, by now, the general lesson had been learned, but the evidence suggests that it has not. Time and again, broadcasters have crept back to indulge in another bit of cultural necrophilia, with wildly varying degrees of success. Dad's Army, Steptoe And Son, Are You Being Served?, Keeping Up Appearances, Porridge, Till Death Us Do Part, Still Open All Hours, Birds Of A Feather and The Vicar Of Dibley have all been revived, re-cast and/or reimagined, and, Up Pompeii! only escaped the same sad fate when Miranda Hart was unavailable to take over from the late Frankie Howerd.

Is it all just a little bit of history repeating? Does it really matter?

Well, yes, it does. Hegel famously said that all great things in history happen twice, and then Marx, even more famously, added that whilst the first time is tragedy, the second is farce. In the history of sitcoms, however, that order is reversed. Great sitcoms start with laughs. If revived, they almost always end in tears.

There is something profoundly embarrassing about broadcasters who strain to seem so progressive in terms of image while being so backward-looking in terms of practice. The best programme-makers of the past - so often patronised and sneered at in some of today's smug 'weren't they quaint' retrospective documentaries - at least made an effort to do something new. That is one thing that might be worth copying.

So let's have less of the imitation and more of the innovation. Less of the 'you have been watching' and more of the 'you will be watching'.

Do you really want to honour the memory of the classic shows? Then either leave them in peace or repeat them, and learn from them, and then try to make completely new sitcoms that are good enough to become classics in their own right. You never know, as a policy, it might just catch on.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreYes, Prime Minister - Series 1

The hit political sitcom returns with a revamped, refreshed run, 25 years after the final episode of the original series.

With European economies going down the toilet, a tempting energy deal from an unusual source, a leadership crisis with his coalition partners, a Scottish independence referendum and the greatest moral dilemma he has ever faced... there's lots for PM Jim Hacker to deal with.

The ultimately powerful but beleaguered Prime Minister is once again 'assisted' by his impenetrably loquacious Cabinet Secretary, Sir Humphrey Appleby, and torn but sensible Principal Private Secretary, Bernard Woolley. There is one person definitely on his side though: Policy Unit Head, Claire Sutton.

The six episodes are set in Chequers, the country residence of the Prime Minister and observe the unfolding drama as Hacker tries to negotiate Britain out of a financial crisis.

First released: Monday 25th February 2013

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Catalogue: 2EDVD0809

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Fall And Rise Of Reginald Perrin - The Complete Collection

This definitive collection includes all 21 episodes from the three series of The Fall And Rise Of Reginald Perrin, as well as an array of additional features which are new to DVD, including the post-Reggie series The Legacy Of Reginald Perrin and a special 1982 Christmas sketch.

The Fall And Rise Of Reginald Perrin remains one of the greatest comedies ever broadcast. From a terminally frustrated commuter who fakes his own suicide, to the boss of Grot, a shop selling useless junk, to running a commune for the middle-aged and the middle-class, Reginald Perrin - and his family and colleagues - provided a hilarious satire on modern life.

The magnificent performance of Leonard Rossiter held the series together, but the show also boasted David Nobbs' consistently witty scripts and a supporting cast of fantastic characters and a host of enduring catchphrases.

The series The Legacy Of Reginald Perrin (made after the sad death of Rossiter) saw the return of Jimmy, CJ, Tom, Doc and the others, as a deceased Reggie's will inspires them to do something totally and utterly absurd. And, from the BBC's The Funny Side Of Christmas (which featured festive versions of top comedy shows) comes a five-minute sketch of Reggie's Christmas Day.

The Comedy Connections documentary on the making of the series completes this comprehensive collection.

First released: Monday 27th April 2009

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 5

- Catalogue: BBCDVD2365

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Tuesday 5th May 2009

- Distributor: E1 Entertainment

- Region: 1

- Discs: 4

- Minutes: 630

- Subtitles: English

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.