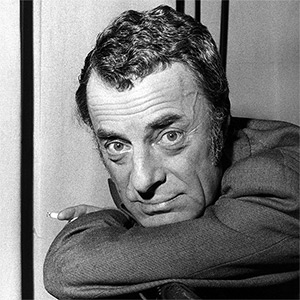

The Quiet One: The understated art of Hugh Paddick

One of the saddest ironies of modern life is that, although modesty is still often mentioned as an admirable quality in a character, one is more likely to be under-appreciated for actually embodying it. In the more superficial of social circles, those who don't shout the loudest and elbow others out of the way are deemed immediately to lack the ability to do so, rather than simply possessing the decency to behave so much better than that. Hugh Paddick was one such comic actor, and one such human being, and it is for that regrettable reason that his profile remains considerably lower than that of many of his contemporaries.

Take, for example, his involvement in the much-loved radio show Round The Horne. People readily remember the host, Kenneth Horne, and the outrageous Kenneth Williams, and, to a somewhat lesser extent, the only long-serving woman in the team, Betty Marsden, but Hugh Paddick often ends up being referred to as 'the other one', the 'whozit', the 'wotsisname', the contributor who requires a caption.

That was Hugh Paddick. He was a clever, gifted, versatile comic performer, and a fine professional, but he never pushed himself forward, so he often found himself pushed back.

The critic Kenneth Tynan talked about 'high-definition' performances - the kind that impress themselves upon you through the precision and power of their process. Paddick could deliver those. What he chose not to deliver was a high-definition personality. He was an actor; not a star. He did his job and then went home. He had no craving for fame.

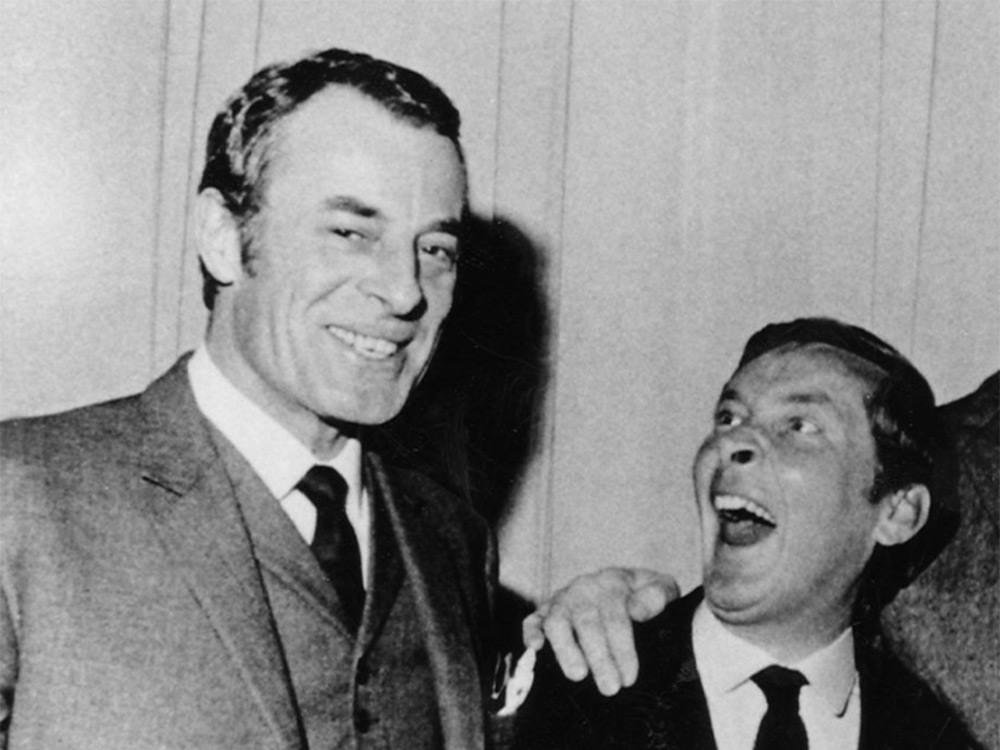

That's what made him such an ideal partner for Kenneth Williams: always unselfish and understated, he complemented rather than competed. While Williams concentrated on the broad brushstrokes, he was content to add the fine details. It was why Williams, who so often came to clash with his fellow performers, never had a bad word to say about Hugh Paddick.

No one had a bad word to say about Hugh Paddick. He was commonly regarded as being one of the classiest and most decent people in his profession.

Barry Took, who with Marty Feldman and others wrote some of Paddick's best-remembered sketches, praised his performances as being 'touched with an élan rare in show business,' while describing his personality as 'courteous, amusing, talented and kind,' judging him 'a natural gent' and 'one of the nicest people I've ever met'. Kenneth Williams himself would write admiringly of 'H.P' in his diaries, calling him 'v. kind' and even admitting that Paddick's performances contained 'v. subtle & brilliant things' that, by comparison, made his own seem 'very crude'.

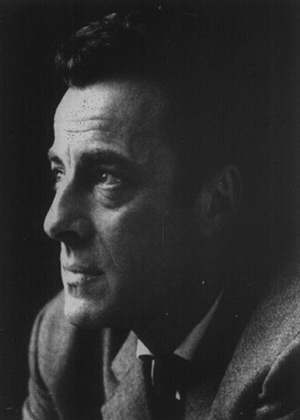

Such elegant reticence was no doubt due in part to something natural in his character - he had always been, from an early age, a gentle and generous soul - but it was further nurtured by an environment in which the idea of 'showing off' was seen as a sign of superficiality. Born in Burford Street, Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, in 1915, to a family of farmers (his parents, Herbert and Christabel, specialised in growing watercress), it had been hoped that Hugh would grow up to become something 'respectable' like a barrister, but, after failing his bar exams, he disappointed his parents by enrolling at a drama school instead.

It was not that he ever wanted to 'show off'. What he wanted to do was to act. He was fascinated by other people, other characters - their differences, their distinctiveness, their defining details - and felt driven to see how well he could resemble them.

Tall, good-looking and always immaculately dressed, he was groomed for leading roles by his tutors, but even at that early stage he seemed keener on losing himself in a role rather than losing the role in himself, exhibiting an elective affinity for the secondary characters, the figures with more complexity about their complexion, instead of those whose flaws and frailties tended to be flattened out by the glare of the spotlight. Making his stage debut in 1937, he would go on to specialise in being a non-specialist, playing a wide range of characters that included a middle-class London doctor, a dour Scottish caretaker, a timid husband, a working-class Italian-American fugitive, a foppish English aristocrat, a Greek soldier, a shrewd young detective, a Cockney butler, a pompous Oxford academic and a morally-compromised army officer.

As an able pianist and singer, he was also much in demand in musicals and revues, winning numerous enthusiastic notices for the energy and invention of his performances (he took to styling himself, with a sort of verbal arch of the eyebrow, as 'a straight actor gone wrong'). The outbreak of the Second World War interrupted his professional progress - he would serve in the Royal Artillery, rising to the rank of an officer - but, once peace returned, he went from strength to strength back on the stage. There were spells in rep at the Camberwell Palace and the Liverpool Playhouse, where he won many friends, and then he made his mark in London's West End.

One of his first notable successes was in the period musical Two Bouquets, which opened in London during 1953 and attracted considerable attention in the months that followed. Paddick, playing a cheerful young man-about-town, was repeatedly singled out for praise, with one critic declaring, 'If Mr Hugh Paddick is not a major comedian [...] in a couple of years, I shall be both sad and puzzled'.

It would actually take him less than half that length of time. At the start of 1954, he was one of the stars of Sandy Wilson's hit musical-comedy The Boyfriend. Playing the part of Percival Browne, a pompous old gentleman, he was hailed as one of the most promising comic actors of his generation.

His career took another leap forward in 1957 when he became the single member of the London company of For Amusement Only to be retained for its subsequent Broadway production. He followed that by appearing in the first London production of My Fair Lady, playing Colonel Pickering after Robert Coote stepped down.

It would be radio, however, that would establish Hugh Paddick as a nationally well-known star. In 1958, he joined Kenneth Horne, Kenneth Williams, Betty Marsden and Bill Pertwee (along with, briefly, Ron Moody, Stanley Unwin and the singer Pat Lancaster) for the new series Beyond Our Ken. Featuring a fast-paced sequence of sketches and a succession of increasingly familiar comic characters, it was ideal for someone as versatile and talented as Paddick, and he revelled in each role.

His regular incarnations would come to include Stanley Birkinshaw, whose ill-fitting dentures caused him to stutter and splutter over every word ('You ashk a shilly question and you'll get a shilly anshwer!'); Ricky Livid, a preciously world-weary young pop star whose appreciation of other performers' recordings rarely went beyond 'I liked the backing'; and Cecil Snaith, a hapless BBC reporter who usually ended his broadcasts abruptly by exclaiming, 'And with that, I return you to the studio!' There were many other one-off and occasional characters - never merely 'voices' - that Paddick contributed, all of them interacting with the others with fine style and fun.

The show soon established itself as one of radio's comedy highlights, reaching into as many as twelve million homes on a weekly basis. Running for seven series over the next six years, it only ended after its main writer, the somewhat misleadingly-named Eric Merriman, fell out with the BBC and refused to do any more.

The BBC responded in 1965 by continuing with the basic format under a new name, Round The Horne, and new writers, Barry Took and Marty Feldman, along with the old cast. A few of the most familiar Beyond Our Ken characters were simply renamed for the revised version (in Paddick's case, for example, Stanley Birkinshaw returned as 'Dentures'), but several fresh ones were created by Took and Feldman. Among Paddick's additional figures was the Cockney concubine Lotus Blossom, the blustering Colonel Brown-Horrocks of MI5, the palmist and seer Madame Osris Gnomeclencher, and the sibilant strolling thespian S. Lupino Moustrouser.

Probably his two most popular characters were the 'ageing juvenile Binkie Huckaback' and the waspishly emotional chorus boy Julian. For the next three years they would help make Paddick one of the most popular comic performers in Britain.

Binkie Huckaback, along with his partner Dame Celia Molestrangler (played by Betty Marsden), had been based on the very grand theatre stars Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. Always taking roles as 'Charles' and 'Fiona' in such parodies of Noel Coward-style melodramas as Present Encounter and Bitter Laughter, they would gleefully over-egg the dramatic pudding with their slow, deep and quaveringly emotional delivery:

FIONA: All I could think of, back here, was you, out there, thinking of me, back here, thinking of you, out there - back here. Needing you, wanting you, wanting to need you, needing to want you...

CHARLES: ...I don't have the words for it.

FIONA: I know.

CHARLES: I know you know.

FIONA: I know you know I know.

CHARLES: Yes...I know.

Julian, meanwhile, along with his even more excitable friend Sandy (played by Kenneth Williams), were inspired by all of those repertory actors who, thanks to the alternative attraction of television, were now finding themselves 'resting' for longer periods than ever before, and, as a consequence, were having to take on various menial 'civilian' jobs in order to survive. Took and Feldman had originally envisaged the pair as elderly hams, called 'J. Behemoth Cadogan' and 'T. Hamilton Grosvenor', but John Simmonds, the show's producer, felt that, given their bleak and hopeless decrepitude, they sounded far more sad than funny, and he therefore urged the writers to make them young chorus boys instead.

They thus became Julian and Sandy (named after two of Paddick's former patrons, the playwrights Julian Slade and Sandy Wilson), who each week appeared offering a new and highly improbable pop-up service, always under the banner of 'Bonar' (such as Bonar Law, Bona Tours, Ballet Bona, Bona Pets and Bona Grapplers). It was quite a daring move by Took and Feldman, seeing as, at a time when practicing homosexuality was still illegal in Britain, the couple were not only very camp but also communicated via the kind of 'Polari' slang that was associated with the gay community, and the scripts were always written so as to make the heterosexual Horne serve as the one who was mocked, but Paddick and Williams knew exactly how to play them, and also how far they could take them.

It did not take long before the writers, and the actors, started blending the parts with the performers. Julian, for instance, in spite of all his flamboyance, was quite Paddick-like in the way that he would let Sandy dominate the proceedings, and say far less about himself ('I like to keep myself to myself,' he would say. 'Ooh, he's quite withdrawn, he is,' Sandy would confirm), while Sandy (like Williams) would waffle away at will.

Julian was allowed the odd moment of excitement (such as when he exclaimed upon entering Horne's apartment, 'Oooh, look, Sandy - a parquet floor! I should have brought me tap shoes!') but more often than not he would be left to react to and reflect on whatever Horne and Sandy discussed. Like Paddick himself, he liked to stand by and step in to dot the 'I's, cross the 'T's and wink the eye, such as here in 'Bonar Hunt':

SANDY: 'Course, Reynard's classical trained.

JULIAN: Oh, yes. He's got your full classical.

SANDY: Started in John Cranko's Nutcracker and worked his way up.

JULIAN: He supported Dame Margot's Sleeping Beauty when Nureyev backed out.

HORNE: And he's the only other member of the hunt, is he?

SANDY: So far - but we're hoping to attract your show business clientele.

HORNE: And where do you hunt from?

JULIAN: Oh, here - in Carnaby Street.

HORNE: But there can't be many foxes in Carnaby Street!

JULIAN: No. Not foxes. There's not what you could call a plethora of foxes round here - but you still have the thrill of the chase.

HORNE: The chase? But what can you find to chase in Carnaby Street?

SANDY: Ooh, he's very jejune, innee, Jules?

JULIAN: Mmm, it's a quality I admire in him. Would that I still had it!

He was also depicted (again like Paddick) as the more demure of the two when it came to anything vaguely sexual. Upon learning, for example, that Julian had recently been rescued from a boating accident, Horne inquired, 'And were you dragged up on deck?' to which Jules replied, 'No, not really, just a casual sweater and slacks'.

The sketches always began with Horne, like some sacrificial lamb, being led to one or another of their latest companies, where they would pounce on him hungrily with their standard greeting ('Oh hello, I'm Julian and this is my friend Sandy! How bona to vada your dolly old eek again!') and then subject him to a succession of double entendres. The start of the 'Bona Caterers' ('We can handle anything') sketch is typical of how, invariably, it developed:

HORNE: Good morning.

SANDY: We are Bona Caterers - that is to say, Jule and me - we can cater for your every function.

JULIAN: Right from your Hunt Ball down to your intimate at 'ome.

SANDY: Just give us a free hand and we'll give you a 'do' your guests will never forget.

JULIAN: Now, then, what's the occasion?

HORNE: It's my birthday party - I'm thirty-nine.

JULIAN: Ooooh, ha-ha! Do you hear that, Sand? Thirty-nine?!?[/b]

SANDY: Hmm, yeah, round the neck he's thirty-nine! So you'll want a cake?

JULIAN: We can do you something pretty bizarre in marzipan.

SANDY: How about Dundee, Jule?

JULIAN: Yes - I could let myself go in Dundee!

SANDY: Ooh, yes, he could let himself go in Dundee, Mr Horne, he could!

JULIAN: Or I could do something provocative in a sponge - with a fruit filling...

Paddick loved the show, and loved being part of that talented ensemble. He grew very close to all of his colleagues, enjoying their company in and out of the studio, and, in his own discreet way, delighted in the success their shared efforts achieved.

Radio, as a consequence, became Paddick's second-favourite medium, occupying a place just below the theatre in his affections. Shielding sounds from sights, it suited his protean talents as a character actor, allowing him greater precision in the delivery of each telling detail. It also suited his disposition as a person, providing him with (along with a strange but reassuring kind of semi-privacy) the sort of relaxed and mutually supportive working atmosphere in which he felt most at home.

He would never be so comfortable in movies or television. The stop-start nature of the filming, and the limited nature of many of the roles he was offered, made such media, for him, seem more of a chore than a pleasure.

Movies, in particular, failed to showcase his talents to anything like the extent that they deserved. It was, indeed, surprising how few comedies of the period found even a modest place for him - none of the Carry Ons, for instance, made use of his comedic abilities, even though he could have greatly enhanced any of their instalments with his subtle style of mischief - and it was only via a couple of his friend Frankie Howerd's big screen ventures that he made any real impact on the cinema at all.

Both of these productions were released in 1971. In the first, Up Pompeii, he played a priest, but still had relatively little to do or say other than conduct a solemnly spiritual bingo ('Moon and Sun, thirty one...Horn of Plenty, Number twenty...'). He had better luck in the second, Up The Chastity Belt, where he played a decidedly 'flamboyant' Robin Hood opposite Howerd's rebellious loner Lurkalot (ROBIN: 'Well, ducky, what do you think of our camp?' LURKALOT: 'Ooh, I think that's the word for it!').

Paddick did rather better, and was certainly much busier, in television. He was always valued by other comic performers, providing a sensitive and trustworthy foil for the likes of Dora Bryan, Marty Feldman, Benny Hill, Tommy Cooper, Jimmy Tarbuck and Cannon & Ball, and he was also a greatly appreciated contributor to one-off comedy plays, sketch shows and revues.

There was rarely anything on the small screen, however, that truly stretched or satisfied him. He had a spell in the ITV sitcom The Larkins (1963-4) as the indolent lodger Major Osbert Rigby-Soames, but was given relatively little to do (and was hampered by half-hearted make-up that usually left his false moustache threatening to blow away like a bit of Botticelli gauze).

In 1969 he co-starred with Beryl Reid in a BBC sitcom called Wink To Me Only, about an eccentric suburban couple who put their house up for sale not because they want to move but simply because it's the only way to get other people to visit them. Written by Jennifer Phillips, it was unusual in the way that it tended to offer a woman's perspective within the conventional sitcom dynamic, with Reid playing the more active of the two main characters, but was panned by the critics for its 'unfunny suburban silliness' and 'the lamentable thinness of the scripts'.

Paddick's second significant starring role, in Bob Block's 1972 comedy show for children, Pardon My Genie, would prove far more successful. Playing the eponymous magical figure, who pops out of a watering can whenever summoned, he brought a refreshing degree of subtlety to what would otherwise have been a standard pantomime turn, but the need for multiple breaks in filming to set up the special effects left him feeling increasingly frustrated, and he left after the first series (to be replaced by the more docile Arthur White).

That lack of patience was typical of the normally placid Paddick's attitude to television. As far as he was concerned, it was nice a place to visit, but he didn't want to live there.

While the stage work went on, therefore, the TV appearances tended to be limited to deft little guest spots on the likes of Sykes, The Morecambe & Wise Show, Rushton's Illustrated and Alas Smith & Jones. Arguably the most memorable of these was in a 1987 episode of Blackadder entitled Sense and Senility, in which he and Kenneth Connor played a pair of foppish ham actors who were tormented because of their intense superstition regarding 'The Scottish Play'. Clearly relishing the opportunity to interact with a fellow scene stealer such as Connor, he had rarely seemed so happy on the small screen.

It was on radio, however, that he continued to find a more enduring form of pleasure, and he was particularly pleased when, in 1978, he was reunited with his old friend and colleague Betty Marsden for a sitcom called The 27-Year Itch. Written by Barry Pilton and billed as a 'marital black comedy', it featured the pair as the irascible Edward and the no-nonsense Dorothy, a couple who clash repeatedly with their two grown-up children (Sebastian and Hilary) while displaying a deep sense of dissatisfaction with the ongoing state of their own lives.

It was an interestingly edgy entertainment - a rare and welcome alternative to the kind of cloyingly cosy family sitcoms that dominate that area of the genre - and the instinctive understanding between Paddick and Marsden made even the more clichéd elements of the scripts sparkle when they performed them:

DOTTY: You don't understand Sebastian because you don't listen to him.

EDWARD: I don't listen to him because he doesn't say anything to me! I mean, talking to him is like trying to get blood out of an extremely ill-mannered stone! I don't have this trouble with other people. Well, apart from you. And our daughter. He's always so surly!

DOTTY: Some children have a difficult adolescence.

EDWARD: I didn't.

DOTTY: No, well, you're having a difficult time now.

The variations on the same theme grew somewhat strained as the show went on, but it lasted for two series and generated a fair amount of critical praise. It would be one of his favourite engagements from this phase in his career.

Perhaps encouraged by the experience of working again with Marsden, he was tempted into agreeing to be in one more TV sitcom after this: Can We Get On Now, Please?, a 1980 legal comedy for Granada in which Paddick co-starred with Sheila Steafel. It proved, much to his disappointment, to be another mediocre affair (one critic dismissed it as 'a sort of Crown Court with jokes only a great deal less entertaining'), and it seemed to sate his appetite as far as any more substantial projects in the medium were concerned.

There would, in fact, be fewer and fewer sightings of Paddick in any medium over the following ten years, which seemed to be the way, at that stage in his life, he preferred it. He had always politely declined invitations for talk shows or newspaper interviews; now, if anything, he grew more withdrawn than ever, keeping a profile about as low as an actor of his stature could manage. It was surely significant, in this sense, that the one panel show in which he had ever enjoyed appearing as himself, Call My Bluff, was more about misdirection than revelation.

One additional reason for this, in an age when cruelly 'outing' someone's sexual identity was becoming increasingly common, was that Paddick, although perfectly secure about his own sexuality among those whom he trusted, had no desire to have it dragged, in a non-Round The Horne Polari way, across all of the newspapers. He had, from early on in his adult life, his preferred places for cottaging, his chosen locations for passionate assignations, but he planned any such occasions carefully, knowing all of the ways and means that might be required for a sudden escape, and there was never any of the rash risk-taking that others were often prone to take.

He had been with his partner, Francis (any mention of his surname, Paddick let it be known, was verboten, and thus, out of respect, is also omitted here), since the late Sixties, when he met him at a party, and he remained fiercely protective of their privacy as a couple. They were far from reclusive, but when they socialised with friends - and they did so often - it was always well away from any cameras.

He spent the last ten years or so of his life in unofficial retirement, spending his days with Francis at the home they shared at 1 Marquis Court, in Woburn, Bedfordshire. Both being keen amateur gardeners, they were frequently to be seen tending to all of the plants around their house, and Paddick was much-admired locally for his kindness, humility and good humour.

When he died, on 9th of November 2000, he slipped away as unobtrusively as he would have wished. There was none of the noise that marked the passing of his old friend Kenneth Williams: no front page headlines, no double-page spreads of tributes and (thanks in part to the fact that his press cuttings file had remained so thin) not even that many detailed obituaries. As happens with most modest people, Hugh Paddick was mourned in a modest manner.

This was not, however, what his talent really merited. The quiet and classy delicacy of Paddick's comedy performances should have won him far greater praise than he received, both in his lifetime and after it, and if we require such subtlety to be amplified in order for us to appreciate it, then that is our failing, and not his.

It might well seem unfashionable in this age of chronic self-exhibition, but Hugh Paddick managed to be a fine entertainer without exhibiting any need for his ego to be stroked, nor demanding that anyone paused reverentially to vada his dolly old eek. The only loud sound required, in his case, is that of the applause he so richly deserves.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more