Hugh & You: The amiable acting of Hugh Lloyd

In comedy, you need a fool, but, just as crucially, you need someone who takes the fool seriously. Few played that latter character more aptly and artfully than Hugh Lloyd.

All the way from the 1950s to the early 2000s, he was one of comedy's crucial links between the inside and the outside of the nonsense, able to appear ordinary enough for audiences to sympathise or identify with, while also seeming odd enough for the other characters to engage with. It was a top-class balancing act, as subtle as it was sound, and it made many a comic situation seem as real as it was risible.

How did he do it? He cultivated the technique and the temperament to blend the blandness of his background with the mischief in his mind.

Born in 1923 at 7 Raymond Street in Chester - a short stroll away from the city's Roman-walled centre - Hugh Lewis Lloyd was the only child of a father (Robert) who worked as a factory manager for a local tobacco manufacturer, and a mother (Maggie) who was a pianist and music teacher. Educated locally on a scholarship at The King's School, his parents hoped that its reputation for high standards would rub-off on Hugh, but, after being taken to see a concert party at Llanfairfechan in North Wales at the age of seven, he was already, he would later say, 'hooked' on the idea of performing, and he drifted through lessons dreaming of making it on the stage.

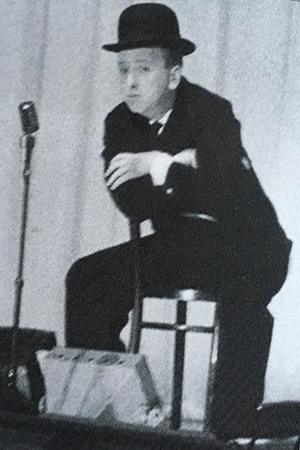

Not even a persistent stammer could undermine his ambition, and he worked so hard at controlling it, if not entirely overcoming it, that he would win a prize for oratory on two separate occasions during his time as a student. He also persuaded his mother, who had recently founded her own amateur choral group called the Deva Ladies Singers, to let him perform some recitations as a kind of warm-up act for their concerts. Hugh even managed, through sheer persistence, to make his formal public debut at the age of fourteen by appearing in a very minor role in a popular play of the time called The Housemaster, by Ian Hay, at the Chester Theatre Club.

Pressured by his Methodist father into at least making an effort to find and hold down a 'proper' job, he spent his first three years after leaving school, from 1939 to 1942, working as a cub reporter for the Chester Chronicle, but not only continued to pursue his acting ambitions in his spare time (founding the Chester Repertorygoer's Club and the Hugh Lloyd Repertory Revue Company), but also - while hiding behind a pseudonym - awarded himself multiple positive mentions in the paper for his performances (judging himself 'a versatile and resourceful comedian' who 'greatly amused' his audiences).

Upon reaching conscription age, he volunteered for the RAF, which turned him down (due to his chronic hay fever), as did MI5 (although they appear to have been sufficiently impressed to have invited him to try again when he was slightly older), so he took a radio-operator's course for the Merchant Navy at Colwyn Bay in Wales. It was while he was there (in spite of having to cope with the impact on his speech of replacing all of his teeth with a full set of dentures) that he once again found an outlet as a performer, aiming to entertain troops around the world (although he wouldn't actually go any further than the British Isles, the Faroe Islands and Iceland) for ENSA as a member of George Thomas's Globetrotters.

He continued doing much the same thing once the war was over as a regular contributor to ENSA's successor, Combined Services Entertainment (CSE). This time he did get to travel further afield, performing for troops in Germany and Austria and at numerous bases across the Middle East, not only appearing as a comic but also writing sketches and humorous songs for others in the company.

He was able to start doing various club gigs in and around London during the breaks in his tours with the CSE, and he also, from the late 1940s onwards, began getting the odd invitation to appear first in radio and then television. His debut in the latter medium arrived on 13th November 1950 in a BBC forces' show, filmed live at London's Nuffield Centre, entitled The Centre Show. He did not yet have much of an act, and as a consequence did not make any significant impression, but the break encouraged him to keep thinking about, and working on, the sort of persona, and material, that would suit his particular talent.

Lloyd always identified instinctively with the underdog. He came from a family that was liberal with an 'l' that was both lower and upper case, had been patted on the head by David Lloyd George when he was four (bestowing on him, he would say, a lifelong 'interest in the ladies and the Liberals'), and had grown up with an outlook on life that was, as he put it, 'You and Me,' and never 'Us and Them' (when, quite late in life, the media office of the Conservative Party asked him to participate in its next party political broadcast, his brusque reply was that he would much rather jump off Beachy Head). This attitude would help characterise his comedy.

He liked to play 'ordinary', flawed, vulnerable, ostensibly downtrodden but quietly defiant and essentially good-natured human beings, and much preferred it if he, rather than anyone else, was the butt of the basic joke. While he thus took his training by playing a wide range of types and temperaments, he felt most comfortable as one of the common crowd (that memorable response to the 'You're all different!' line in Monty Python's Life Of Brian - 'I'm not!' - could, in all its delicious irony, have been written expressly to be delivered by Hugh Lloyd).

Once he settled into a substantial stand-up comedy routine, he shaped a style that was marked by a kind of mock-lugubriousness that he dubbed 'Fun in Gloom' ('I can't stand comedians who laugh at their own jokes'). Telling stories about the various frustrations and setbacks he had suffered, he invited audiences to identify with him as a shop-soiled kindred spirit.

It worked. Apart from the broad appeal and basic believability of his material, he also had something that all comedians crave but only a few - even if they try to fake it - actually have: he was likeable.

He was, as a consequence, quickly in demand, and during the first part of the 1950s he was touring the London circuit alongside the likes of Clive Dunn, Freddie Frinton, Cardew Robinson and, in some of his final appearances, the veteran music hall star George Robey.

He also had a spell at The Windmill, where he won plenty of praise for the quality of his 'dead-pan topical patter'. It was the most intense training ground for comics of that era - six solo spots per day, six days per week, working from noon until 11pm each day, in front of what was invariably an all-male audience who, impatient for the next nude revue, were in no mood for that particular form of amusement - and Lloyd emerged from it toughened-up (with his heavy-lidded eyes no longer looking scared of silence) and armed with a treasure trove of attention-catching tricks.

He would thus be ready to make the most of a major break on television when it arrived. He had already been playing the odd peripheral part, here and there, since the mid-Fifties, but the exposure intensified greatly from 1957, when he was added to the ensemble of supporting actors in the hugely popular sitcom Hancock's Half Hour.

His many roles on the show, over the next few years, would include a chip shop owner; a man queuing at an immigration desk; a librarian; a launderette assistant; a lift attendant; a ship's steward; a booking office clerk; an usher; a council official; a police sergeant; a television engineer; a tree inspector; and a clerk of the court. On each occasion, looking like the younger and chubbier brother that Stan Laurel had left behind in England, he proved that he was one of the best of the first wave of British TV comedy character actors, because he seemed to understand immediately and instinctively just how attentive the cameras could be, catching the slightest widening of the eyes or downturn of the mouth, and so he held back, listened to the other characters, and made the viewers watch him and try to think his thoughts.

He was never cleverer, nor craftier, in this sense, than during the dialogue he shared with Hancock in the classic Blood Donor episode. Resting on neighbouring beds after each has surrendered his precious pint of the red stuff, backing up each other's blandness like bore-ends ('Do you know,' Hancock exclaims, 'that could've been me talking!'), encouraging each other to blow out yet more air-bubbles of idiocy from the wishy-washy nonsense that's sloshing around inside their heads, Lloyd is as fine as any 'serious' actor could be.

As usual, he plays his character perfectly for Hancock's deluded buffoon ('Are you a doctor, then?' he asks respectfully. 'Well, no, not really,' comes the self-consciously casual reply, 'I never really bothered, y'know...'). There is a kind of kinship here that is almost as touching as it is pathetic as one fool becomes fascinated by the other.

'Yes, I suppose it is,' is Lloyd's key line of compliancy, the one of the many that encapsulates the whole frail firmament of his hopelessly friable character. One suspects, looking at his sweetly-blank mashed potato of a face, that just about anything that Hancock says, no matter how stupid or smug or stern or silly, will be rewarded with exactly the same raised-eyebrow show of meek respect. 'Yes,' he'll keep saying, 'I suppose it is'.

Take this exchange, which comes just after Hancock, with breathtaking idiocy, has just, supposedly, 'explained' the workings of all the organs in the human body:

LLOYD: What would we do without doctors, eh?

HANCOCK: Or, conversely: what would they do without us?

LLOYD: That's true. That's very shrewd.

HANCOCK: The main thing is: look after yourself.

LLOYD: You look after your body, and your body will look after you.

HANCOCK: Very wise. 'Cause, the Greeks, they knew all about this years ago, y'know?

LLOYD: Did they really?

HANCOCK: Yes! Very advanced people, the Greeks were, you know? Yeah. They had hot and cold water and drains. Always washing themselves, they were. Of course, it all got lost in the war.

LLOYD: When Mussolini moved in?

HANCOCK: [Looking momentarily unsure] No, no, before him, surely, wasn't it? No, they taught it to the Romans, and then the Romans came over here, and they sort of, um...er...

LLOYD: Well, you can always learn from other people, can't you?

HANCOCK: Of course you can. That's why I'm in favour of the Common Market. You can't ignore the rest of the world.

LLOYD: That's true. That's very true.

HANCOCK: You can't go through life with your head buried in the sand.

LLOYD: 'No man is an island'.

HANCOCK: You're right. There I agree! 'Necessity is the mother of invention'.

LLOYD: It certainly is! Life would be intolerable if we knew everything.

HANCOCK: I should say it would! My goodness, yes! Yes: 'Let the shipwrecks of others be your sea marks'.

LLOYD: 'For things unknown, there is no desire'.

HANCOCK: Well, exactly! And then again: 'A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush'.

LLOYD: 'Tis indeed!

HANCOCK: Do you like wine gums?

LLOYD: Ooh, thank you very much!

It was scenes like these with Hancock that brought Lloyd to the attention of a broader range of potential employers within television, and it was not long before his rather sad and vulnerable-looking face became something of a fixture in small screen comedy - a sight (like the sound of his milky gargle of a voice) that, thanks to his essential amiability, was not only familiar but also increasingly welcome.

His potential for more substantial roles was certainly noted by the boss of the BBC's entertainment output, Tom Sloan. Late in 1961, Sloan had received a script from the comic writer John Chapman that required a pair of leads who could play a sort of British version of Stan & Ollie, and, once he had persuaded the producer/director David Croft to take on the project, he suggested Hugh Lloyd and Terry Scott as its two stars.

Croft was quick to agree. He had known both actors for several years, having worked with them in the mid-Fifties when he was putting on summer shows at various British seaside resorts for Butlins Holiday Camps.

His first impression of Lloyd as a performer had been, on the whole, a positive one. 'To be honest,' Croft would later say, 'Hugh didn't have an act worth mentioning, but he performed with such disarming charm that no one seemed to notice'.

He had a similar reaction to Terry Scott, finding him a 'funny performer,' even though finding his material 'feeble'. Having gone on to watch him be the first of the two to make his mark on TV, alongside Bill Maynard in the sketch show Great Scott - It's Maynard! (1955-6) - a series, incidentally, in which Lloyd made some guest appearances in minor roles - Croft did wonder how Scott might respond to the change of having Lloyd as an equal instead of an underling, but the combination of their characters appealed to him and he was looking forward to seeing how the dynamics developed.

The sitcom they were due to share was called Hugh And I. Scott was cast as a lazy but aspirational bachelor (who still lived with his mother at 33 Lobelia Avenue in Tooting, South London), and Lloyd as his gullible lodger. There was no great overarching theme for them to explore, other than the essential silliness of men trying to act like 'proper men' as they searched for work, tried to impress their neighbours, struggled to get dates with women and generally did whatever they could to sleepwalk safely through each day-dream.

It would always be something of a challenge to work with someone like Terry Scott. As David Croft once remarked, while Lloyd as a person was 'always a delight,' Scott had an ego 'big enough to sink The Titanic,' along with the kind of temper that, whenever it darkened - and it all-too frequently did - would rattle the windows like thunder as its owner raged about everything from fluffed lines to late-arriving sandwich breaks.

The two men (who had first met back in the mid-1950s, when both were appearing in summer season at Weymouth) actually worked very well together. They shared a car each day as they drove in to rehearsals at Acton, running through their dialogue as they travelled so that, by the time that they arrived, both were word-perfect.

They also clicked in front of the camera. Scott was a restless soul, his round and dimply face forever in jelly-like motion, while Lloyd kept a carapace of calmness about him. Scott was the talker, Lloyd the listener; while the former acted, the latter reacted. Together, they moved each other on like the cogs connecting two wheels, a comic mechanism that ticked and tocked along like clockwork.

Gradually, however, a degree of tension developed behind the scenes, mainly because Scott - always a self-conscious stickler for maintaining high standards - managed to convince himself, mistaking subtlety for slothfulness, that the far more laidback-looking Lloyd was not working hard enough. David Croft brushed away all of his increasingly common complaints about this as 'rubbish' - 'Hugh worked quite as hard as Terry,' he later said, 'but it just didn't look like it' - but the carping never stopped.

It didn't help that Scott remained so personally insecure that he grew resentful of Lloyd's burgeoning popularity with both the production crew and the general public (when The Observer newspaper invited readers playfully to suggest who they would like to see as president in place of the monarch, Lloyd made it to the top two - much to Scott's fury). In order to reassure himself that he, rather than Hugh, was the 'real' star of the show, he resorted to all kinds of ruses that Lloyd - although always managing to rise above it in public - privately found 'trivial and stupid,' such as insisting that he was paid a few pennies more than his colleague to symbolise his supposed superiority, and demanding that he be interviewed and photographed first if ever there was any publicity work to be done.

'He even made a point of pronouncing the title of the show differently to everyone else,' Lloyd later reflected. 'Whereas we all emphasised the "Hugh" in Hugh And I, Terry always emphasised the "I"'.

Thanks to the popularity of the sitcom, however, the two men would remain tied together for the rest of the decade. Running for six series between 1962 and 1967, the show was always high in the ratings, never threatening to challenge the likes of Steptoe And Son in terms of critical acclaim but serving, nonetheless, as one of the most reliably entertaining middle-of-the-road shows of its time. After the writer John Chapman declared that he had exhausted all of his ideas, the BBC remained keen enough to bring the characters back for a sequel, called Hugh And I Spy, in 1968. Even during the gaps between filming, the offers Lloyd and Scott received as an unofficial double act were so lucrative that they teamed up for several theatre and night club tours, and also appeared together in several pantomime seasons.

Hugh And I, in its various iterations, finally came to a close following that series, but the pair were persuaded to continue working together on TV in a new sitcom called The Gnomes Of Dulwich. A socio-political satire by Jimmy Perry about the squabbles between various ornamental figures who come to life in a south London garden, it was about as unconventional as sitcoms got in those days, and the popularity of Lloyd and Scott was thus deemed crucial in counteracting the puzzlement the concept was expected to engender.

Lloyd, when promoting the new show, still talked-up their 'close' off-screen friendship, telling interviewers how much time they liked to spend together socialising, especially at football games ('We're both soccer fanatics,' he said. 'Terry supports Watford and I support Chester. We go together to see as many matches as we can'). His co-star, somewhat tactlessly, would give reporters a much cooler and contradictory account of their connection: 'We have nothing in common,' declared Scott sniffily, 'except the sense to appreciate the other person'.

If Lloyd got to read such comments, his disappointment was almost certainly much greater than his surprise, because he had already endured Scott at his very worst during the making of the sitcom. Problems with costumes and make-up - concerning both the time it took to get prepared and the discomfort that was caused from toiling beneath the heat of the studio lights - as well as with the difficulty of projecting any kind of recognisable personality from within all the prosthetics, had troubled everyone on the set, but Scott, as usual, had reacted with the loudest voice and the most terrible tantrums. 'People wanted to shoot me after that sitcom,' Scott would later admit in a rare moment of self-awareness. 'I wanted to shoot myself!'

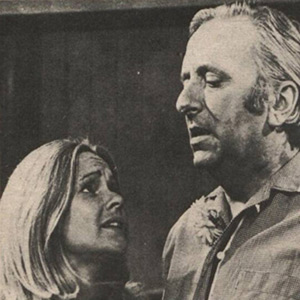

It was something of a relief, therefore, when Scott was not invited to take part in the next project that Lloyd was offered: another Jimmy Perry-scripted sitcom, this one called Lollipop Loves Mr Mole. Produced by ATV, it paired Lloyd with Peggy Mount as a late-married couple living in suburban London, whose hopes of belated domestic bliss are undermined by the unwelcome arrival of his feckless brother Bruce (played by Rex Garner) and his fragile wife Violet (Pat Coombs).

The 'odd couple' dynamic between the rather timid and neurotic Reg (Lloyd) and the tougher and testier Maggie (Mount) echoed that between Hugh and Terry, although Mount brought to her character a more focussed kind of aggression to the sort that Scott had spluttered out. Lasting for two series, the comedy might not have been as stable and steady as that supplied by Hugh And I, but, with Mount, Lloyd at least had a more mature working relationship, and he was grateful for the feeling that his contribution was better appreciated.

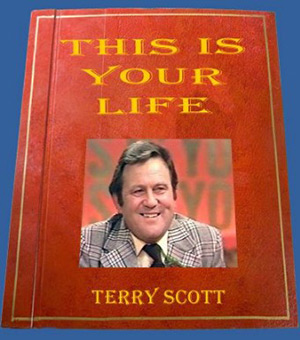

There would, however, be a predictably dispiriting little coda to his collaboration with Terry Scott that came some years later. When the TV show This Is Your Life was planning to surprise Lloyd as the subject of one of its episodes, Scott (who would later, in 1978, be a subject himself), upon being sounded out about taking part, affected a look of regret when he told the production team that his old friend had already stumbled on the secret - thus causing the whole programme to be scrapped. 'This was absolutely untrue,' a saddened Lloyd (who only heard anything about the matter many years later) would say. 'It was just Terry's way of making sure I didn't get any of the glory, which was just so typical of him'.

Unaware, at the time, of this final petty and cowardly act of betrayal, Lloyd laboured on regardless, still receiving more than enough offers of work in television, movies, radio and theatre to enable him to pick and choose his projects with rather more time and care than many of his less fortunate contemporaries. It was from this position of relative security that he launched, in 1977, his own sitcom for children - devised by himself - called Lord Tramp.

He played Hughie Wagstaff in the show - a carefree homeless man who, much to his surprise and discomfort, inherits a fortune along with a massive mansion and surrounding estate. It was a gentle comedy, very much driven by character, and he was delighted that it seemed to please its young audience.

Lloyd's personal life during this time, rather surprisingly given his amiable nature, was sometimes as shaky as his professional life was stable. Often prone to sudden infatuations, and not the most resistant to the temptations to be encountered on tour, he married no fewer than four times.

His first wife, Anne Rodgers, was a fellow ENSA performer. They married in 1948, but only stayed together for a couple of years, after both of them acknowledged that they were better-suited to just being friends. His second marriage, to the concert pianist Josie Stewart (the fact that her real name was Mavis Grigg seems to have misled some biographers into assuming that he must have had an 'extra' wife), was a much more stable relationship, beginning in 1958 and lasting for a decade.

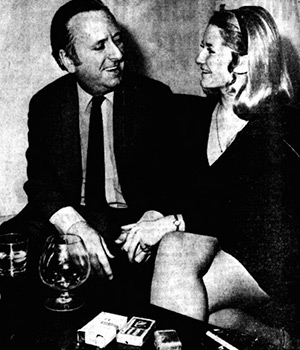

Perhaps in the midst of something of a mid-life crisis, he left Josie for a former art teacher called Carole Giles - who at twenty-nine was seventeen years his junior - in 1969 ('We don't agree on any subject,' he had told reporters when announcing their engagement, 'but we get on very well together'). With him being busy, and her unemployed without any apparent ambition, the union seemed doomed from the beginning. 'Inevitably,' he latter reflected, 'the boredom led to her having affairs and after a while we split up'.

He would be luckier when he met his future fourth wife, the Fleet Street crime reporter Shân Davies, at Joe Allen's restaurant in London's West End during 1978. Although she was half his age, they made each other laugh, would marry in 1983, and remain together, very happily, for the rest of his life.

As for Lloyd's public profile, he seemed to disappear for longer stretches than expected during the Seventies, and that was because of the new demands on his time in Australia. He had first gone there in 1969 to join a touring production of the John Chapman and Ray Cooney farce Not Now, Darling. Running for a year, it was a big box office success, and Lloyd - who was already a familiar figure in the country thanks to the popularity of Hugh And I - was so touched by the warmth of his welcome that he resolved to return more often in the near future.

He thus jumped at the chance to shoot a sitcom in Sydney at the start of the Seventies with his old colleague David Croft. Originally entitled Strike It Rich, but then renamed Birds In The Bush before ending up as The Virgin Fellas, the show - devised by a somewhat eccentric Australia-based Hungarian businessman named George Rockey - was written and directed by Croft and starred Lloyd (as an Englishman who has inherited a farm in the Outback) alongside an Australian actor called Ron Frazer and seven young women described as 'sexy tomboys'.

Croft would be remarkably candid about how he had crafted the programme. Charged with the task of making a sitcom (aimed at the international market) about the country's current boom in nickel mining, he admitted to having 'sexed-up' the basic storyline, out of desperation, in order to bring in a broader audience. 'The girls are in the show of necessity,' he said, 'because I fear the finding and losing of a nickel fortune is not a terribly exciting comic theme'.

The project proved quite a troubled one from start to finish. A pilot was made in March of 1970, and, after a series was commissioned, filming was disrupted and delayed during the summer when Lloyd (after drinking water from what was later found to have been a contaminated cup in the studio canteen) fell ill with hepatitis, and David Croft was called back to London by the BBC before his work on the programme could be completed. When various other directors and writers managed to finish the thirteen episodes in August 1971, it was screened on Australian TV later in the year to what Lloyd himself later claimed somewhat fancifully was a response that rendered the show a 'smash hit,' but which might, more accurately but still generously, be described as 'mixed' reviews.

David Croft eventually managed to get the series shown on the BBC in the summer of 1972, but it was judged a spectacular failure and was dropped midway during its run. The critics certainly left no one in any doubt as to how much they loathed it - 'it was loosely written,' claimed one, 'amateurishly played and the situations were far too obvious'; 'Television situation-comedy has plunged, in my view, to an all-time low with the dreary, unfunny series from Australia, The Virgin Fellas,' argued another. 'Please, somebody, take it away!' - and it ended up being branded by one newspaper 'the worst comedy show of the year'.

Undeterred, Lloyd would continue visiting Australia on and off for the next few years, as much for the weather as the work. Ever the sentimental Cestrian, however, he made sure that, even on the beach, he still had an imported copy of the Chester Chronicle close at hand.

Back in England, in the early 1980s, he moved from his large home at East Sheen in south-west London to a house in the village of Rottingdean near Brighton, and then, about ten years later, moved again to an apartment in Dolphin Lodge, on Grand Avenue in Worthing, West Sussex, with an expansive view of the sea and the pier. Now married contentedly to Shân, he took to travelling with her on cruises, during which they appeared on stage together, with her interviewing him about his long career.

There was never any chance, however, that he would ever stop acting, and he remained busy throughout the rest of his life. He did start to tire, eventually, of what the pros call 'shouting at night' - theatre work - but otherwise he stayed very much engaged.

He worked during his later years with a wide range of comic performers that included Victoria Wood, George Cole, Leslie Phillips, Jimmy Cricket, Sheila Hancock, Ardal O'Hanlon and Lee Evans (the latter of whom called him 'a fantastic bloke and a brilliant comedian,' and said of his 'timing, his delivery, his professionalism in interpreting our lines - he neither did too much nor too little'), adapting to each context and cause with rare flair.

Among his most memorable roles would be in the Alan Bennett television plays A Visit From Miss Protheroe and Me! I'm Afraid Of Virginia Woolf (both broadcast in 1978); a couple of episodes of Doctor Who as a Welsh beekeeper (1987); a regular role in In Sickness & In Health (1990-92); and he was reunited with David Croft and Jimmy Perry when cast as Selfridge the butler in their sitcom You Rang, M'Lord? (1991-3).

He also, before cutting back on his stage work, spent a year with the National Theatre between 1995 and 1996, at the invitation of Sir Ian McKellen, appearing in Chekov's The Cherry Orchard, Sheridan's The Critic, and Webster's The Duchess of Malfi, and, during the same period, took part in the Chichester Festival revivals of the 18th-century romp, Lock Up Your Daughters, and Hobson's Choice. Another notable residency in the decade was at one of his favourite venues, Theatr Clwyd, where he played in lighter comedies such as Sailor Beware!, while spending his leisure time watching his beloved Chester City.

One of the best of his projects from this later period would be his contribution to the Anthony Hopkins movie called August (1996). Filmed on the Lleyn Peninsula, it was an adaptation of Uncle Vanya, reimagined as taking place in the milieu of the landed gentry of 1890s Caernarvonshire.

Being Hopkins' directorial debut, he had taken a major interest in the casting, and asked for Lloyd specifically to play the part of the elderly neighbour Pocky Prosser - a pathetically parasitic sort of character. He chose Lloyd (whom he regarded as a 'great') because he knew that he could rely on him to supply the subtler colours of comic characterisation to contrast with, without any jarring, the increasingly intense emotional tones of the central characters.

Lloyd had also appeared in the preparatory stage version, which was presented, like the movie premiere would be, at Theatr Clwyd (with its main auditorium being renamed 'The Anthony Hopkins Theatre' in honour of both occasions). 'Have a laugh,' the director told him, 'and don't spare the prat-falls or the trips'. He didn't, and his experience - he would call it 'magical' - would be matched by that of his audience.

'[W]atching an actor like Hugh Lloyd perform,' Hopkins would reflect, 'something inevitably comes through - a deep, fundamental grasp of the ridiculousness of the human condition, with its priceless self-importance, its futile struggle in an incomprehensible world. I suppose that's what acting is all about, and Hugh Lloyd is an exquisite example of this gift, this talent to amuse - to break one's heart'.

The odd good notice, however, tended to get overlooked by those who focussed on what, and who, was now fashionable, and, as a consequence, fewer people seemed aware that Hugh Lloyd was still around. In November 2002, The Stage newspaper, which one might have expected to have known what an actor was or was not doing, wrongly described him as 'retired' - an error that moved Lloyd to write in to correct the report, albeit very politely, with a list of his most recent credits. 'I should like people to know,' he added, 'that I am still at it'.

Those who did still notice him certainly still appreciated him, because they realised that he - unlike so many of those from a younger generation who were now straining and failing to emulate his style of acting - was so good at making it all seem so easy. In an age when so much comedy characterisation could not resist resorting to a mood-wrecking wink and a nod to the audience, Hugh Lloyd still played it straight, and kept it funny.

Awarded an MBE in the 2005 Honours List for his services to drama and charity, it took his autobiography, Thank God for a Funny Face, to shine a little light on the individual hiding behind this comic everyman. Lloyd tried to sum himself up in its pages by saying: 'I will tell you what I am not, and hope never will be: a snob, a chauvinist, a Wrexham football club supporter or a Tory'.

It was left to his friends and colleagues to complete the description by telling people what he was: good and kind and always delighted to make others laugh.

He died, aged eighty-five, at his home in Worthing on 14th July 2008 after a very short illness. He was mourned by his many admirers as one of the craftiest comic spirits they had seen.

'Ere,' cried a startled Tony Hancock after that classic bedside conversation, 'he's walked off with my wine gums!' He also, more often than not, walked off with the scene as well.

Help British comedy by becoming a BCG Supporter. Donate and join us in preserving, amplifying and investing in comedy of all forms, from the grass roots up. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more