The heart of the matter: The real battle of Hugh Carleton Greene

One of the worst injustices in British broadcasting's treatment of its own past has been its depiction of Sir Hugh Carleton Greene as merely a supporting player in the chronically skewed saga of Mary Whitehouse and her self-appointed mission to clean-up TV. Greene is actually one of the true giants of the medium, responsible, directly or indirectly, for making possible many of the most courageous, imaginative, innovative and inspirational achievements that the form has ever seen, and yet, when he is remembered at all today by journalists and documentary makers, it is usually as nothing more than some kind of peevish stooge to a demagogue's arrogant prattle, as one-dimensional as Blakey in On The Buses ('I 'ate you, White'ouse!').

This is, quite simply, an outrageous and shameful distortion of the real facts of the matter. It is easy enough to establish what those facts of the matter actually are. One just has to start at the beginning of the story, rather than shamble in mid-way through.

The story really begins in the late 1930s, just before World War Two, with the battle against fascism. Hugh Greene would play his part in that fight, and his perspective, as a consequence, was shaped profoundly by the intolerance and atrocities that he witnessed, and the virtues and values that came so close to being crushed.

Born on 15th November 1910 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, Greene had grown up in a relatively privileged environment as part of a large and influential family that included scholars, bankers, barristers, businessmen, bureaucrats, diplomats, politicians and the owners of Greene King Brewery. His father Charles was the headmaster at the local public school, his mother Marion (a cousin to Robert Louis Stevenson) was the daughter of a Cambridge academic-turned-Bedfordshire vicar, and he was educated at Merton College, Oxford.

All five of his siblings would go on to lead interesting lives of their own. One brother, Graham, would of course become one of the most celebrated novelists of the century, and another, Raymond, made his mark as an eminent doctor, explorer and mountaineer, while a sister, Elisabeth, would work for MI6. The Greenes, it seemed, were groomed for greatness.

Hugh - a giant of a man, at almost 6ft 6in tall, with his eyes magnified by his spectacles and his manner a mixture of cool detachment and shy mischievousness - began his own adult life as a journalist, reporting for the Daily Telegraph first in Berlin (where he rose rapidly to the role of chief correspondent before being expelled by the Nazis in May 1939) and then on to Warsaw, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, the Netherlands, Belgium and finally France. The work, and disposition, of a reporter suited him so well that he would say he never considered himself an 'ex-journalist' at any time after.

Following a short spell in the RAF as a pilot officer in Intelligence, Greene was released in 1940 to join the BBC's German Service as its news editor. It was from this initial base that he would start to build a broadcasting reputation that would reach throughout the media world: Controller of Broadcasting in the British Zone of Germany (1946-48); Head of BBC East European Service (1949-50); Head of Emergency Information Service, Malaya (1950-51); and Assistant Controller, and later Controller, BBC Overseas Services (1952-56).

His attitude throughout the conflict was to fight fearlessly to keep the facts in circulation. 'If we lost the war,' he later reflected, 'if there was a German invasion, we'd all be shot anyway, so why not tell the truth? Whereas if we held out and the tide turned, the fact that we told the truth would mean that the German people would believe us, as indeed they did.'

It would be hard to over-estimate the extent to which this whole deeply eventful period impacted on Hugh Greene's moral outlook. He saw and felt it all, from the earliest days of Nazism, when those dead-eyed dogmatists he called the 'gangsters' first began rallying for their reign of hate, to the post-war period of de-Nazification, when he played a leading role in reforming a culture still rooted in crime and cruelty.

He was in Berlin during 1938 to see young children painting white stars of David on the windows of Jewish-owned shops, while older city residents set fire to synagogues as their Jewish neighbours were dragged off into what was being euphemistically termed 'protective custody'. He even found himself, on one occasion later in the same year, standing just behind Hitler and Goebbels at the Potsdamer Bahnhof, as truth headed for the scaffold and wrong for the throne, where the sight of him towering over the two of them provoked much semi-stifled sniggering amongst the youngest of their arm-thrusting followers.

In April 1945, he was one of the first of the liberators to walk through the dust and rubble, past the old abandoned cattle trucks, and into Dachau concentration camp, where, while American soldiers were falling to their knees vomiting from the stench and the sheer horror of the place, he saw large piles of emaciated corpses either side of an incinerator waiting to be cremated. Stooping skeletal figures in striped pyjamas started shuffling out from the shadows and crowding around him, touching his arms and kissing his hands.

These were the memories, from those multiple seasons in hell, which would never leave Hugh Carleton Greene. They were scored on his soul.

'I learnt to hate intolerance,' he later wrote, 'and the degradation of character to which the deprivation of freedom leads.' He went on determined not simply that such barbarism would never happen again, but also that whatever aspired to its opposite - all of the compassionate and creative graces of a properly civilising spirit - should be embraced, endorsed and actively supported.

Returning to London in the mid-1950s, he found that the BBC, under the aegis of Sir Ian Jacob, was already edging tentatively in a progressive direction by modernising its means (investing more in television) and engaging more actively with its audience (more out of pragmatism than principle, given the new need to compete with commercial companies). Sir Ian, spotting a kindred spirit with even stronger convictions, started supporting Greene as his ideal successor.

Such patronage proved productive. Climbing up the Corporation with remarkable rapidity, Greene spent just two years as Director of Administration, and then a couple more as Director of News and Current Affairs, before reaching, in 1960 at the age of forty-nine, the pinnacle of power as Director-General.

He was the new man for the new decade, and he knew it. It was time to move on, to stop looking back and start looking forward, and encourage a culture and a society that was starting to refresh itself from within.

There was a palpable sense of the Establishment bracing itself for what it feared was coming. Billed by the more dry-mouthed of observers as 'the new broom', there were even some (albeit a minority) of his more conservative colleagues within the Corporation who were muttering in private that, as one of them would put it, he had 'got the stuff of which Cromwells are made'.

The Cromwellian reference, though not intended as a compliment, would prove to be rather prescient, because Greene wanted the Corporation, much like Cromwell had wanted Parliament, to reclaim its power rather than search for it anew. Greene's own Magna Carta was the one from 1927, charging the BBC with the task of providing information, education and entertainment 'to the best advantage and in the national interest'.

What Greene wanted, therefore, was not to make the BBC start doing something radically different. He wanted it to start doing what it was already supposed to be doing, but with far greater energy, efficacy and élan.

'Public service broadcasting,' he said, 'only exists to serve the public,' and to do this in the best manner, and to the greatest extent, it must fight against being 'tied to a rigid pattern,' and 'resist pressure groups and ill-informed criticism,' and 'dare to be experimental and adventurous'. This, as he saw it, was his mission to encourage.

Gathering his new staff together, he noted that 'most of the best ideas must come from below, not from above', and told them to 'go ahead and make mistakes'. He made it clear that he meant it.

'I wanted to open the windows and dissipate the ivory tower stuffiness which still clung to some parts of the BBC,' he later explained. 'I wanted to encourage enterprise and the taking of risks. I wanted to make the BBC a place where talent of all sorts, however unconventional, was recognised and nurtured, where talented people would work and, if they wished, take their talents elsewhere, sometimes coming back again to enrich the organisation from which they had started.'

This was what began happening in the news division, where the traditionalists in radio were made to wake up belatedly to the relevance of television and improve the interaction between the two, and the whole network was rapidly modernised. Under his personal guidance (Greene retained for himself the function of editor-in-chief), a more journalistic sense of rigour was brought to the researching and reporting of events and issues, a greater degree of editorial independence was defended in relation to multiple political pressures, and far more effort was invested into ensuring that the flow of information and opinion between the government and the governed was fair and full in both directions.

The changes were also soon evident in the drama department, where (driven by the likes of Sydney Newman) there was a marked increase in the diversity of writers, themes and styles, and programme-makers were pushed to explore the full richness of the genre, and the technical range of the medium, in their pursuit of high quality, thought-provoking, engaging entertainment. In everything from series such as Z-Cars, Doctor Who and The Forsyte Saga to single drama showcases like The Wednesday Play, the new confidence and courage soared through the system.

The same kind of impact was witnessed in the BBC's approach to so-called 'light entertainment' as a whole, which was reinvigorated by a rare mix of in-house mavericks led by Eric Maschwitz. Appreciating (unlike, then and now, most of the people in Parliament) that entertainment is as much an intrinsic, and cross-fertilising, element of public service broadcasting as is information and education, Greene demanded not only the highest of standards but also the boldest of ambitions.

Nowhere in this area was such a pursuit more passionate than in the Corporation's comedy output. Fine young writers, such as Peter Cook, Alan Bennett, John Cleese, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, David Nobbs, Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais and Johnny Speight, were nurtured and nourished, and the range of programmes and projects expanded accordingly, with the richer emotional colours of Steptoe And Son mixing with the unflinchingly raw realism of Till Death Us Do Part, the youth-orientated The Likely Lads, the women-orientated The Rag Trade, the subversive and sometimes surreal wit of Not Only... But Also... and a whole new wave of satirical shows in the form of That Was The Week That Was in 1962, Not So Much A Programme More A Way Of Life in 1964, BBC-3 in 1965 and On The Margin in 1966.

The Greene era was, in short, a period in which programme-makers felt trusted, writers encouraged and performers appreciated. It was also a time when the public, rather than being seen merely as some tummy to be tickled, were treated instead with proper respect, a broad and thoughtful audience that deserved to be challenged and surprised as well as pleased and satisfied.

To suggest, however, that all of this happened without any internal opposition and resistance would be quite wrong. There was always plenty for Greene to push against, and there were always plenty who pushed against Greene.

One of the most obdurate and outspoken of these was one of the BBC's most powerful executives. His name was Tom Sloan.

Tom Sloan, the Dulwich College-educated son of a Scottish Free Church minister, had replaced Eric Maschwitz in 1961 as Head of Light Entertainment, a Tory presiding over a bunch of Whigs. It was a recipe for tempestuous times.

As Bill Cotton, who worked under Sloan at the time, would tell me:

Tom was a decent man, a good man - I was very fond of him - but he was very conservative and very, very, moralistic, and he knew how to work the BBC machine. He would always be a very stark defender of what he considered to be the BBC's 'proper' position. He had very fixed views as to what the BBC should do and what the BBC should not do - and he didn't care who it was he was challenging on that matter. He made, for example, an attack on That Was The Week That Was that was brilliant in its articulacy. Absolutely. And there was another occasion when he clashed with Alasdair Milne [a producer at the time] about the same show - he absolutely tore him to bits at a Wednesday Review meeting. And he wasn't at all afraid about arguing with Carleton Greene, either. He was most protective about what Greene tended to be most dismissive about - basic run-of-the-mill entertainment programmes - and most critical about what Greene was most positive about - the 'controversial' stuff. He was always slamming the table and shouting 'The rot starts here' about those programmes that he felt were too eager to shock and offend. But he was never just some blustering reactionary. He was articulate, passionate and sincere, was Tom, and his was not a voice to be ignored.

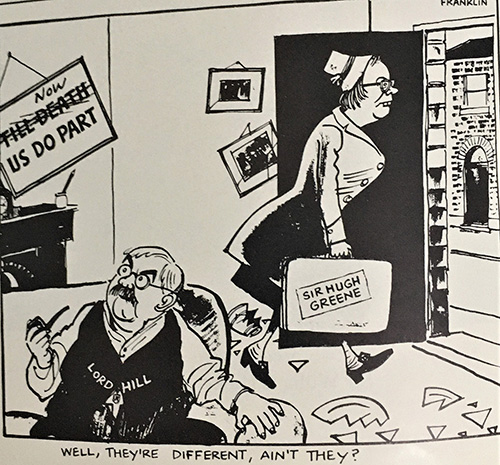

One of the programme-makers, and programmes, that caused the most frequent and ferocious clashes between Greene and Sloan was Dennis Main Wilson and Till Death Us Do Part (a sitcom that Sloan had tried and failed to strangle at birth). On-screen, for the viewing public, the show would be infamous for its arguments; off-screen, behind closed doors, it would be just as infamous for its arguments about its arguments.

Main Wilson, a veteran of The Goon Show and probably the most irrepressibly outré of all the BBC's outliers, had served under Greene both during (in the BBC's European Service) and immediately after the war (at Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk), providing anti-fascist propaganda and then implementing the process of de-Nazification. They had been through the same things, shared the same values and continued to fight for the same freedoms.

To Sloan, on the other hand, Dennis Main Wilson was an irresponsible maverick who had neither the time nor the respect for (most of) his bosses, never bothered to think-through all of the possible consequences of his commissions, and who was now, in the mid-Sixties, conspiring with Till Death Us Do Part's working-class writer Johnny Speight to embarrass, outrage or even corrupt large parts of British society with their irreverent, sexually, racially, socially, politically contentious and even (some felt) sacrilegious content. 'Tom Sloan,' Main Wilson would confirm, 'was a very good administrator, but he thought I was evil. He thought I was breaking the consensus as to all things Good, with a capital G, and British, with a capital B.'

The result was that every single episode, every single week, sparked a fresh battle between Sloan and his producer, with the former trying to defend the status quo and the latter demanding the right to shake it. The degree of executive interference was both unprecedented and unrelenting.

'He'd phone me up sometimes straight after transmission,' Main Wilson later recalled, 'and say, "You filthy swine! My office - first thing in the morning!" And there I'd be accused, again and again, of letting the side down.'

Sloan took to scouring each script for offensive content, scribbling complaints in the margins and striking out sentences or sometimes entire sections that he judged to be unacceptable, and he often distributed a copy on to the heads of other departments, such as Religious Broadcasting, so that they, too, could find something reprehensible in its text. He also started trying to enforce quotas for the words which he hated - Speight was limited, for example, to twenty 'bloodies' per episode - and would often visit the set during rehearsals, standing in the shadowy background with arms folded and face frowning, to register his disapproval in person of whatever they were doing that day.

Even when - as was often the case - the show won plenty of critical and public praise, Speight would say that Sloan was still likely to react with anger:

We did this episode in the second series called Sex Before Marriage. Now, by this time, we were getting audiences of about twenty-two million, twenty-three million, and we were getting magnificent notices from the TV critics of the time. And this episode made the front pages of all the newspapers that week, it had a huge impact. And the following day I went to the recording of the next show, and there was a message waiting saying, 'Would Dennis and Johnny go up to see Tom Sloan as soon as possible'.

So we went up there, and me - naïve as I was in those days - I thought, because of the huge audiences and magnificent notices, maybe we were finally going to get congratulated. But instead of that, the first words we heard from Tom Sloan as we walked into his office were: 'Dennis, you have let down the BBC!' And to me he said, 'And you - if I'd have known what you were up to, you would never have got the show on here! You have betrayed me and the BBC!' I just said, 'Tom, you're mad!' and walked out, leaving Dennis to get another blasting.

It was then, as usual, that Greene stepped in to support the show for its readiness, as Speight liked to put it, to 'grass on all of Britain's bigots':

After the recording, they put drinks on for us in the BBC One Controller Kenneth Adam's office, because Sloan didn't want us talking to all the journalists who were waiting to interview us at the bar in the BBC Club. And Kenneth Adam himself walked in holding up a telegram, saying, 'Gentleman, I have a message from our leader' - meaning Carleton Greene. And he read it out: 'Great show last night. Keep up the good work. I'm 100% behind you!'

And Dennis - whose ears were still ringing from his latest telling-off - said, 'Well, Tom didn't like it'. So Kenneth Adam walked over to Sloan, put his arm around his shoulder and said, 'You old fuddy-duddy, Tom, you'll never learn!' So that was that. But the next week, he was raging again, cutting stuff, trying to block stuff. He was always at it, he never stopped!

Dennis Main Wilson would himself attest to the many times that the show, and his own career, were saved by the Director-General's timely interventions:

Every Tuesday morning, Tom Sloan threatened me with the sack. By Wednesday, usually, Hugh Greene would have let it be known that I wasn't sacked. Which helped enormously!

He really supported his team. He was in America once, being interviewed by Time magazine, who were hypnotised by the impact Till Death Us Do Part was having. The interviewer said, 'But surely this must have offended many people?' And Hugh Greene replied, 'Yes, but surely only those that one would wish to offend anyway'. That, to me, is a great D-G: stating exactly where he stands in life, and what his broadcasting corporation is all about. He was a great man. I loved him.

As brutal and bitter as some of these and other arguments were between Greene and Sloan, they actually provided the BBC with a very urgent and intense top level editorial process throughout this extraordinary era. If Greene won many of the battles, he did so only after a fierce but fair internal fight.

It was Sloan's chronic concern about the danger of the BBC descending into moral turpitude that ensured that what might have been a monologue always remained a dialogue. While Greene pushed for rights, Sloan pulled for obligations. While Greene rallied to the risk-takers, Sloan fussed over the possible consequences of their actions. While Greene was usually ready to push forward, Sloan usually found it preferable to press pause.

Greene, contrary to the way that he is routinely caricatured these days by the chroniclers of the 'Clean-Up Britain' brigade, welcomed alternative opinions and relished internal debate. Given all that he had been through, he would have been the last person to have wanted his own views to have been met with meek submissiveness. He cherished each chance for those on either side of an argument to talk, listen and think, and emerge at the end, as he put it, 'with a deeper knowledge of the other'.

He regarded Sloan, therefore, as his own Socratic gadfly, an alternative moral voice that merited proper respect and serious reflection. The tension between the two men thus formed the BBC's own progressive dialectic during the 1960s. It provided the grit that helped make so many pearls.

This is not, however, the impression one gets from the vast majority of popular discussions of this period (most of which, quite ridiculously, do not even include Sloan in their accounts). Arriving unwittingly late in the day, fluffy boom mics floating sleepily up to the skies and cameras blinking slowly open into the light, the documentaries tend to start, like Whitehouse did, long after Sloan had started - thus creating the grossly misleading impression that Greene had been getting his own way on just about everything, and it would now take the abrupt intervention of a plucky Christian conservative school teacher from the provinces to drag him kicking and screaming back down to earth.

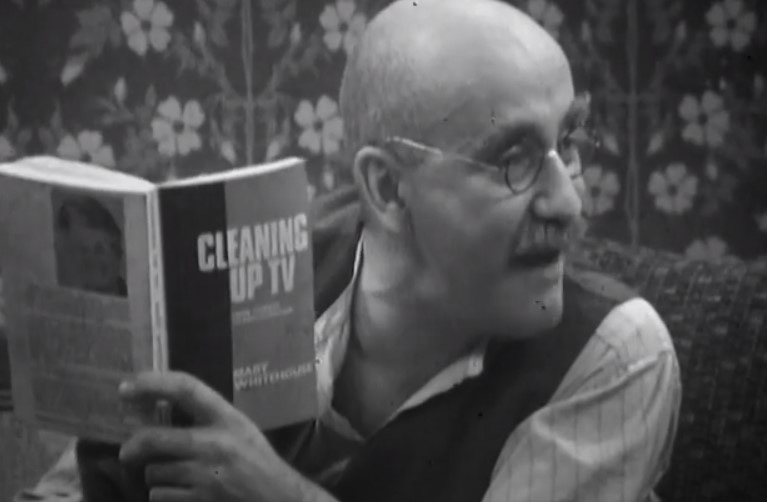

The common suggestion is that Mary Whitehouse woke Britain up to the BBC's 'wanton abuse' of its power and influence. Having convinced herself that Greene, in her typically intemperate and Manichean language, was 'the devil incarnate' who was encouraging all of his employees to promote 'the propaganda of disbelief, doubt and dirt [...] promiscuity, infidelity and drinking,' and infuriated by his apparent disinclination to keep pausing his publicly-funded duties to pay her his full attention, Whitehouse sustained a spiteful and spurious narrative in the press that, because the Director-General was ignoring her dissenting voice, he was ignoring all dissenting voices.

The fact that the likes of such insiders as Tom Sloan (along with the far from timid BBC Governors) had already been, and were still, making similar points about programmes, but with far greater knowledge of what was actually happening, and with far greater intelligence, self-reflection and sophistication - thus rendering her, for all her sound and fury, not an original voice at all but merely an irritating echo - appeared to have been missed by this self-appointed spokesperson for the whole of the United Kingdom. It was not missed by most in the media, but to have acknowledged it would have spoilt a story that they were clearly relishing keeping running.

Similarly, some politicians, then like now, were only too happy to play the populist card and applaud each one of Whitehouse's megaphoned sermons on the mount. It was, in fact, a cynical act of hypocrisy by them - akin to demanding that a Prime Minister, after going through the normal interrogative processes of Parliament, should then go through it all again, but this time in an unregulated and unbalanced manner, in accordance with the on-the-hoof rules of some random member of the public.

Hugh Greene's response to Whitehouse's regular rants was actually no different to what a Prime Minister's would surely have been in similar circumstances. He simply noted that, far from avoiding such an inquisition, he had actually already gone through it and emerged out the other end.

There is always, unavoidably, a huge amount of abstraction and presumption involved in any claim by a public officer to be serving the interests of the nation in general, and certainly any such assertion should be questioned regularly and rigorously by some or other responsible and representative body, but there is nothing either 'democratic' nor dutiful about submitting to the singular whims of a Mary Whitehouse, or the neighbour of Mary Whitehouse, or the neighbour's neighbour of Mary Whitehouse, simply and solely because she or he happens to shout the loudest.

When Hugh Carleton Greene, wearying of all the draining internal and external battles after nine remarkable years in charge, finally stepped down as Director-General on the last day of March 1969, Whitehouse, of course, was quick to claim his departure as her personal victory. 'I do not want to sound offensive,' she declared with risible insincerity, 'but my first feeling is one of great relief,' adding that she had never felt that he (unlike, presumably, her) 'was able to reflect the spirit of the country'.

Whitehouse (who became so pleased with herself that she boasted to having 'far too much respect for my own mind' to bother to actually see some of the things that she wanted censored) would not be the only contemporary figure keen to wash away all of Greene's real and many achievements. In an act of quite astonishing cant hardly befitting of a God-fearing 'wee free' Calvinist, Tom Sloan would actually try to take some of the credit for, of all things, the success of Till Death Us Do Part, including it as one of the shows 'I would not mind being remembered for'.

Greene, who always had far more class than most of his critics, kept his counsel on this kind of pompous nonsense. After a spell as a BBC Governor, he advised numerous other broadcasting organisations in multiple countries, edited (amongst other things) four short story anthologies under the series title of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, and became chairman of his brother Graham's publisher, The Bodley Head. He also continued to combat dogma and dictatorships in any way that he practically could, winning more praise for doing so from those abroad than he ever did from those at home.

Since his death in 1987, Greene's own extraordinary achievements as one of Britain's most influential and impressive broadcasters have been strangely and increasingly neglected by the media, while what memory of him that remains has been repeatedly and progressively traduced by those still obsessed with marketing the myth of Mary Whitehouse as 'the avenging angel of middle England'. As acts of self-flagellation go, this would take, pun sadly intended, some beating.

Even the BBC's own recent two-part, two-hour, documentary Banned! The Mary Whitehouse Story (2022), which was so proud of its own research that it featured many self-admiring images of archives being consulted, managed to completely ignore the ineluctably important role of Tom Sloan and his like-minded colleagues, while, yet again, Greene was depicted as a blinkered and aloof member of 'the metropolitan elite' who clearly had no time at all for any alternative opinions. Coming from the broadcaster that Greene, more than anyone else in its entire history, taught to be courageous, this was, at best, clumsy, and, at worst, craven.

It is about time that those who want to chronicle this era in broadcasting properly start paying rather less attention to the demagogue and a great deal more to the Director-General. Contrived contrarianism may serve some sectors of the media's amoral and evanescent needs as clickbait, but there ought still to be room for at least a little bit of accuracy, honesty and integrity.

Hugh Carleton Greene contributed far more of lasting value to British culture and society than his detractors ever did. He was a man whose commitment was not to cliques or controversies but to what he regarded as the core moral values of any decent community: 'truthfulness, justice, freedom, compassion and tolerance'. At a time when public service broadcasting is in desperate need of a hero, it really ought to shine a light on the one in its own history.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more