Gang Aft Agley: The Day TV Broke Hogmanay

There it was, there on the screen: the last dregs of 1984. Now you see it, now you don't. This was TV's latest idea as to how to celebrate New Year's Eve, and it was a shambles. In fact, it was an omnishambles. It was a disaster wrapped in a train wreck inside a horror show. It was such an excruciating mess that it wouldn't have been too great a surprise if 1985 had felt far too embarrassed to ever emerge.

The show in question was called Live Into 85, and it was on BBC1. It was meant to be yet another unsolicited televisual homage to the annual habit that is Hogmanay, but this one was so stupendously awful that it killed that deeply dubious broadcasting tradition stone dead.

It shouldn't have been a great surprise. British television has never really known how to welcome in the New Year. In fact, it has always done its best to avoid welcoming in the New Year.

Before it hit upon its current irrational plan of screening random demographically-divisive music acts before and after the bongs ('Who's it?' 'It's Craig David, Gran'. 'Ray Davies?' 'No, it's Craig - Oh, have another drink!'), it used to try to dismiss the whole occasion as specifically and exclusively 'Scottish,' and handed over the airwaves to its own strange version of Hogmanay. This usually involved a bit of Gaelic music, a bit of Highland dancing and a great deal of someone or other who lived in Berkshire but was very, very Scottish.

One might be tempted to explain this peculiar regional seasonal obsession, at least as far as the BBC is concerned, by citing the lingering influence of the Corporation's first Director-General, the Kincardineshire-born Sir John Reith, but Sir John, as the dourly dutiful son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister, was a staunch teetotaller who would surely have kept his home completely free of the devil's buttermilk, shunned any hastily-defrosted 'party platters' and retired straight to a cold bed with an improving book long before the chimes of Big Ben heralded the arrival of something quite as decadent as midnight.

In fact, during the early post-war years of TV, the BBC was clearly undecided when it came to how, if at all, it should mark this special occasion. At 11.30pm on 31 December 1946, at the end of the first year of television being back on in Britain, the best that our then-solitary channel could muster was something with the shoulder-shrug of a name Seeing The New Year In. No footage of this broadcast appears to have been allowed to survive, but according to contemporary accounts it featured a number of men in dinner jackets standing about at the Grosvenor House hotel in London, talking to each other for a bit, with members of the Dagenham Girl Pipers providing a brief but spirited burst of girl piping.

The BBC, for the next few end-of-years after that, kept on going back to, and sometimes dozing off at, the drawing board. In 1949, for example, it hit upon the rather sweet idea of showing a very brief live broadcast of twenty sleeping babies inside St Thomas's Hospital in London; while the following year it offered only a perfunctory newsreel review of recent events; then in 1951 it settled on a London church service; and in 1952 it really seemed to confuse itself by sending Richard Dimbleby to host a 'New Year's Eve Party' inside St Thomas's Hospital that featured comedy from Janet Brown and singing from Donald Peers.

The tradition of going all-out Scottish appears to have started, as far as TV is concerned, straight after that. In 1953, the BBC decided to see in the New Year, for all four of the countries that it covered, by screening a Hogmanay Party, hosted in Glasgow by two men who would soon go on to become fixtures of this kind of concatenation of kilts, pipes, accordions and reeling and shrieking: the comedian Jimmy Logan and the singer Kenneth McKellar.

This actually made no real sense for the BBC, seeing as Scotland, then like now, only accounted for about 8.2% of the whole UK population, but for some bizarre reason the BBC had convinced itself that, for want of a ready-made broader alternative, it may as well pretend that everyone was Scottish for the best part of the last hour on the final day of the year.

It went on like that for the rest of the decade and far beyond. By 1959, the Logan-McKellar combination was added to by the introduction of yet another future long-serving annoyer from north of the border, the more-beige-than-shortbread Andy Stewart, and then the following year the tartan trio became a Caledonian quartet with the arrival of Kirkintilloch's own red-headed warbler Moira Anderson.

The Glasgow Police (no doubt much to the appreciation of the Glasgow burglars) somehow found the time to feature prominently in these programmes, too: if it wasn't the City of Glasgow Police Male Voice Choir belting out a succession of songs throughout the broadcast, it was the City of Glasgow Police Pipe Band screeching out between the comedy spots. Then there were the Lowland 'folk' performers (whom Billy Connolly would so memorably call 'singing shortbread tins') and an odd assortment of poets and 'traditional' dancers to complete this seasonal splurge of faux Scottishness.

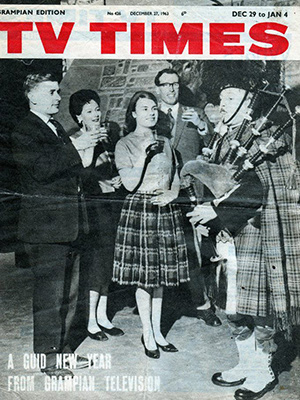

There was no escape by turning over to ITV, because the ever-mimetic commercial network (after being criticised by the press during its earliest times for usually leaving the New Year 'to creep through the keyhole') had swiftly followed suit and gone all 'Monarch of the Glen' itself for each New Year's Eve evening. From the late 1950s onwards, ITV was offering such copycat cèilidh shows as A Guid New Year from Glasgow, A Show for Hogmanay and Hogmanay Party, which featured many of the same old performers, such as Jimmy Logan and Kenneth McKellar and Andy Stewart, usually accompanied by a painted backdrop of heather, snowy hills and a herd of hairy coos.

There was ample evidence that some viewers from outside of Scotland were growing increasingly resentful of this Hogmanay hegemony on British television - one of many angry letters sent to the English tabloids at this time questioned why 'the ritualistic peculiarities of Hogmanay are inflicted on the whole country' - but the networks carried on regardless, as the tartan and the bagpipes continued to dominate the end of the year schedules.

It was still going by the 1980s, even though its increasingly shambolic 'cheap and cheerful' production standards suggested that all of the executives in London had grown so apathetic and insular, snug inside their comfortable metropolitan bubble, that none of them was actually bothering to monitor what was going on in their name 'Up North'. Slurry-voiced and red-nosed late-middle-aged performers, and boozed-up and boisterous members of the audience, were becoming more and more common as the years went on, while the settings (which ranged from dubious-looking 'ski lodges' to run-down local hotels) were getting increasingly seedy.

Worst of all was the comic content. The standard approaches each year seemed to consist of painfully old-fashioned 'us versus them' gags about the English, Welsh and Northern Irish, or meta-Scottish routines (in which relatively obscure Scottish comics would address the idea of Scottishness for non-Scottish viewers, usually with non-hilarious results), or the kind of inward-looking and mediocre local material that only really made much sense to some sections of the Scottish audience.

Even the TV critics, by this stage, were rebelling. The Daily Mirror's London-based reviewer, for example, had raged at the start of the decade: 'Why does the dreaded disease of Hogmanay still afflict television producers every New Year's Eve? It is now four years since the deadly Andy Stewart strain was wiped out, but it hurts just as much. Viewers all over Britain are still made to suffer haggis force-feeding, the whine of bagpipes, the dizzying sight of large men in kilts dancing and other painful symptoms. [U]ntil the Celtic New Year monopoly is broken and the Sassenach majority is freed to enjoy the passing of the year with comedians who speak intelligible English, my TV set goes off at 11.30 every December 31'.

With the arrival of the fateful-sounding year of 1984, however, the more youthful of the BBC's Scottish-based programme-makers vowed to turn the tide. They were adamant that the next TV New Year celebrations were going to be so good, and so inclusive, that a mass of tam o'shanters would be tossed up in the air in triumph soon after the first-footers had burst through the front door.

One reason for this unexpected injection of passion and purpose was the news that there was now another hook to hang the show on. The English National Tourist Board, in a bid to boost UK-wide awareness of live entertainment for the following year, had just announced its accompanying slogan: 'Make it Live in 85'.

This struck the producers as a suitably opportunistic way both to make the end of year show more inclusive for viewers outside of Scotland, and also cause it to seem refreshingly topical and 'relevant' after decades of being rooted in a backward-looking and semi-mythical tradition. For Live Into 85, therefore, they would book some non-Scottish acts, find a suitably 'live' non-studio setting, and show those smug suits in London how to put on a proper show.

Once the summer was over, therefore, the planning picked up a pace. First of all, they chose what they felt would be a suitably glamorous venue: the five star Gleneagles Hotel, near Auchterarder in Perthshire. Apart from being a magnet for golf-playing entertainers, it also had good 'event spaces' for filming and was well-accustomed to accommodating broadcasting crews.

With this base in place, they moved on to book some guests who would hold some appeal to those who were watching from over the border. Tom O'Connor was their choice to host the proceedings. The avuncular, Bootle-born, silver-haired comic and game show host was currently one of the most-familiar figures on British television, and, with his easy-going nature and ability to ad-lib, was considered a safe pair of hands for the production.

They also managed to secure the services of the pop group Bucks Fizz. Having won the Eurovision Song Contest in 1981 with the skirt-shedding routine that was Making Your Mind Up, the band had been enjoying a steady succession of hits since then, and were considered quite a catch for the normally staid and middle-aged Hogmanay slot.

A combination of a fast-draining budget and the difficulty of getting anyone else to travel up for the evening meant that this was about it as far as English stars were concerned, but they did also manage to sign-up the Birmingham-based singer Maggie Moone. She was not exactly a major name, but she was still enjoying a certain amount of exposure at the time as the resident 'hint' vocalist on the ITV game show Name That Tune, and would at least be another fresh presence for the production.

They also managed to recruit probably the one Scottish comic, other than the always otherwise-engaged Billy Connolly, who held real appeal for a non-Scottish audience: Chic Murray. Murray, by this stage, was in failing health, and had struggled in the recent past to cope with this kind of live and potentially chaotic late night broadcast, but his participation was still considered something of a coup. If any performer was likely to please viewers on both sides of the border, it was him.

It was at this point that the craggy auld hands of Hogmanays past seem to drag the programme-makers back towards the line of least resistance, as they filled the rest of the cast with tried and tested members of TV's tartan army: Moira Anderson, the Doric-tinged comedy double act of Buff Hardie and Stephen Robertson, Glaswegian actor and comic John Grieve (best known for being in the Para Handy series), local entertainer Bill Torrance, and, really slicing open the black buns, the Pipes and Drums of British Caledonian Airways, the Jim Johnstone Scottish Country Dance Band and the Tom McShane Dancers.

It seemed a disappointing loss of nerve after quite a novel start, but at least the team had shown willing. They remained, as a consequence, very excited about their prospects of delivering an above-average show.

Then, ominously early, things started to go badly wrong. More than a fortnight before the actual broadcast, they suddenly lost Bucks Fizz.

On the night of 11 December, the band was travelling along the Great North Road on their way back from a gig in Newcastle when their tour bus collided with an articulated lorry, badly smashing the vehicle and sending two of the performers through the windscreen and seriously injuring all on board. All of them survived, but, of course, they were out of action for the foreseeable future.

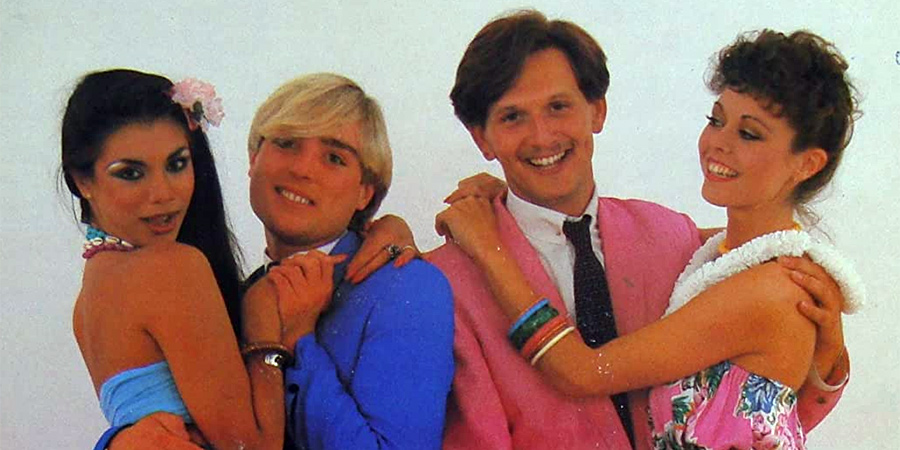

The TV producers up in Scotland, responding to the shock news, had no choice but to hurriedly find a suitable replacement, which, at that stage, was by no means a straightforward task: most well-known and affordable English bands were either already booked for other gigs that night or else disinclined to give up an evening's drinking for a brief TV spot all the way up in Scotland. Eventually, however, following some frantic phone calls, a replacement was found: Modern Romance, another cheerfully inoffensive pop combo from London, whose past hits included the less-than-unforgettable Everybody Salsa, Ay Ay Ay Ay Moosey and Best Years of Our Lives.

The production was back on track, just about, and the preparations continued. There was still a confident 'we'll show them' attitude about the enterprise. ITV's promised offering for that New Year's Eve night was an unashamedly old-fashioned show entitled A Happy Hogmanay! and featuring, quelle surprise, 'Andy Stewart and a host of Scotland's most glittering stars'. The contrast, the BBC team felt, would only serve to highlight their own new spirit of invention and adventure.

Tom O'Connor, being a seasoned professional, arrived a day early in order to 'recce the scene' (and maybe play a bit of golf). He was alarmed by what he found - or rather failed to find.

There was, for example, hardly any stand-by material on tape - which was usually one of the first things arranged for such televised events. This meant that, in the unhappy event of anything going wrong in the ninety minute live show, there would be nothing to fill-in the time on film. O'Connor thus fussed and fumed until the producer agreed to record one of the bands, and a few other potentially helpful bits and pieces, ahead of time. It was, he assured the still somewhat concerned comedian, going to be fine on the night.

When the big night arrived, however, the nerves were starting to jangle. It was, predictably enough, a bitterly cold moonlicht nicht the nicht - no higher than 4°C - and travelling to the location was hazardous. Several participants were late arriving, and there was a mounting sense of tension in the air.

This was when the first major mistake became evident. The BBC production team, in a budget-influenced oversight, had not bought the venue over for their exclusive use.

This meant that the Gleneagles Hotel was full of 'ordinary' people, who had paid considerable amounts of money to eat, drink and be merry on New Year's Eve in a five star establishment, regardless of what any TV crew might want them to do. In other words, as the seats and tables around the stage began to fill up, it soon became apparent, long before the live transmission began, that the producers were going to have to deal with an increasingly rowdy, intoxicated and unpredictable audience.

It did not matter one whit, in those circumstances, what instructions the stage manager might attempt to issue. The punters had paid their money, they were determined to have a good time, and they were going to have that good time in exactly the way that they wanted to have it, no matter what televisual distraction happened to be going on in front of their increasingly blurry eyes.

By the time that the national network surrendered its airwaves to Scotland at 11.40pm, therefore, there was already a twitchy feeling of anarchy in the atmosphere. As soon as the cameras fixed on Tom O'Connor's rictus-grinned face, and he attempted to shout above the boozy audience's bickering brattle (the speakers were not only tiny but they had also been secreted under the tables on the front row of the floor), it was alarmingly evident that this was going to be an unnervingly unpredictable occasion.

The show's arrival on the screen, as one traumatised reviewer would put it at the time, was 'like a belligerent drunk bursting in on a cosy party'. Without any firm control over the hotel guests, many of whom seemed not to have noticed that the filming had actually started, the movement of people backwards and forwards in front of the cameras, combined with the sound of their various conversations, was almost as much a distraction to the viewers at home as it clearly was to the performers on the stage.

The Hogmanay stalwart Moira Anderson attempted gamely to win the audience over with a kind of mash-up of traditional Scottish songs, including Mairi's Wedding, the Uist Tramping Song and Bonnie Gallowa. It was not exactly the shrewdest start to a show that was meant to be confounding expectations about what a Hogmanay show was like, but it seemed, for better or for worse, to get the cheering crowd even more eager to party.

After this, however, everything started to unravel. Technical problems, which would dog the whole show, started to leave O'Connor and the other performers intermittently stranded with a stalled autocue. The odd camera would suddenly shudder as intoxicated revellers crashed into them or tripped over cables on their way out to the lavatories. A singing spot from an alluringly-attired Maggie Moone was wrecked by the fact that a drunken member of the audience was clearly trying, throughout her sensitive rendition of If You Love Me Let Me Know, to peer up her dress, and one other reveller, who was even worse for wear, lurched forward in an attempt to run his hand up her leg ('I'll KILL him!' screamed her husband, who was watching helpless from the wings).

As if to smack a few kilted legs and shake the crowd back somewhere in the general direction of sobriety, The Pipes and Drums of the British Caledonian Airways - who had been stuck out for the best part of half an hour frozen to the bone in the arctic car park - were summoned inside and launched hurriedly into an ear-bleedingly loud performance of Scotland the Brave, but, aside from probably causing a mass outbreak of tinnitus, it failed to curtail the chaos. Tom O'Connor, by this stage, resembled a hostage being repeatedly prodded into confirming his existence, while the technical problems were as bad as ever and there was a constant threat of audience members staggering into shot.

John Grieve should have breezed through his recitation of the Happy New Year poem - he had, after all, not only performed it countless times before but even recorded it as a single - but it soon became painfully apparent that he was not quite entirely sober. After stumbling through the lines, 'As New Year's Eve approaches I get sadder every day/It makes me mad that I get sad for I know I should be gay,' he dried up completely, and then stared around in impotent panic as his moistened forehead seemed to be trying to crawl up and hide beneath his hair. The director, panicking, cut straight back to a stunned Tom O'Connor, shouting in his earpiece: 'Talk to Camera 3 and be funny - NOW!!!'

If that was bad, then Chic Murray's contribution was worse. He was normally a comic performer of real genius, but now, in his current poor health (he would actually pass away just a month later), he seemed utterly baffled by the hubbub accompanying the whole occasion.

Part of the problem was that the pipe band, having finished their ear-screeching spot, had been supposed to have marched back out of the hotel and into the car park, but, presumably feeling disinclined to endure further bursts of icy midnight air shooting up their kilts, they had decided to stay where they were in the warm.

This meant that when Murray, as the designated first-footer, was supposed to have wandered into view with a glass of Scotch in one hand and a lump of coal in the other, he hadn't been able to see the prompt for the pipers. When someone did, belatedly, shove him out and on to the stage, he was so disoriented that he couldn't find his mark or work out where he was supposed to be looking.

Always inclined to goad a distracted audience rather than ignore it, it appeared at first as though his disinclination to proceed with his act was some kind of provocation, but then he started muttering to unseen technical people, asking where the cameras were (they were all around him and he was staring straight into one of them), and it was obvious that even he had been defeated.

The show finally put itself and the viewers out of their misery after one more forced burst of brass-based jollity from Modern Romance, this time performing the horribly inappropriate Best Years of Our Lives. The cameras then cut back to a now-desperate Tom O'Connor, who, having turned the colour of a recently-shaken bottle of Bailey's Irish Cream, started to say, with head-shaking forced jollity, 'You won't believe what I've just seen in the bar...,' and then the plug was pulled and the screen went blank.

The New Year was finally here, and it could not have had a worse start.

The following morning, the Scottish newspapers appeared to be inaugurating a period of national mourning. There was anger, embarrassment and shame of Darien-like proportions expressed in review after review.

The critic for Aberdeen's venerable Press and Journal - Norman Harper - was merely the most emotional in his summary of the significance of the whole sorry debacle:

'Live from Gleneagles,' said the screen. 'Dead from Gleneagles' would have been more apt. This was truly an hour of televised tripe. Dancers birling around, depressing ballads about the good old days, a pipe band drowning out everyone - the same old tosh which, if you think about it, has absolutely nothing to do with celebrating the start of a new year.

John Grieve made the most appalling blunders in washed-up material he has been trotting out for ages. Chic Murray wandered about in a daze berating the floor manager.You could hear the toes curling; you could feel the heat of embarrassment as the whole show whirled gaily down the plughole.

Putting it out on the national network compounded the felony. The whole of Britain was watching us make fools of ourselves.

Soon, someone, somewhere, will bemoan our lack of standing with our neighbours in England, Wales and Ireland. We don't deserve any. We have no defence.

Until we consign all of this tartan nonsense to the dustbin where it belongs; until we shake off our self-inflicted image of a nation of half-canned sentimentalists greeting about the good old days, and until we tap talent and ability worthy of our attention, we should be gagged.

We get so few chances to impress the nation with our true qualities and worth that to throw one away by confirming everyone's worst suspicions about us is unforgiveable.

We have no divine right to force our maudlin tartan mediocrity down the throats of our neighbours in England, Wales and Ireland.

Yes. Live Into 85 really was that bad.

'I've still got the video,' Tom O'Connor would later say. 'It's labelled on the spine: "The Show that Died of Shame"'.

The BBC, as a consequence, seemed to finally wake up to the fact that it had been guilty of a dereliction of (public service) duty every New Year's Eve for about three decades. Stung by all the criticism of this latest disaster, it actually started to make an effort, and, for the next few years (with the exception of 1987, when, insanely, it thought it would be a good idea to have an edition of EastEnders see in the New Year), it hired the likes of Terry Wogan and Clive James to host something that resembled a broadly appealing end of year programme.

ITV and Channel 4 soon followed suit, before they, like the BBC, managed to convince themselves that the entire nation had very conveniently gone down the pub for the duration. Even on New Year's Eve 2020, when the usual excuse that 'everyone will be out' was, thanks to the global pandemic, well and truly null and void, the best that the BBC could manage was an Alicia Keys special ('Who's it?' 'It's Alicia Keys, Gran'. 'Heater fees?' 'No, it's Alicia - Oh, have another drink!'), while the best the rest could manage was, well, nothing much at all.

This year [2021] promises more of the same, which is hardly a surprise, but it still seems a shame. The empirical reality is that the majority of the UK is inside at home at this time of night on New Year's Eve, and in sight of a TV set, so why not make an effort to entertain them, in all their rich variety, when you have such a special chance?

Who knows, you might just win the first unforced whoop of joy in seventy-odd years of end-of-the-year TV.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more