There's something about Hetty: The cross-dressing comedy of Hetty King

Precious few people remember Hetty King these days, but, these days, she is well worth people remembering. Once known and celebrated internationally as 'England's greatest star', she was a masterful cross-dresser, a marvellous performer who put gender on the agenda, and mocked the most dubious, doltish and damning aspects of masculinity more effectively and incisively than anyone else of her era.

Born Winifred Emms in Wallasey, Cheshire, on - it is commonly assumed - 21st April 1883 (her birth certificate has yet to be located), Hetty King was the second daughter of William Emms and his first wife Nora Broderick. She loved going across the river to explore the city of Liverpool ('All the best things come from Liverpool', she would always say), identifying intimately with that part of the country's instinctive and indomitable commitment to mutual respect, justice and equality, and, from an early age, she would spend ages sitting by the Mersey watching the ships come and go, dreaming of where, one day, she might go and explore.

She became a performer at about the age of seven, long before she really knew that she wanted to perform. She was pushed before she had time to play.

Her father, using the stage name of Will King, was an uninspired but undeterrable music hall entertainer (usually appearing in black face) who expected all of his children, regardless of their attitude or abilities, to start contributing to the family income as soon as was possible by joining his various touring ensembles. Winifred thus soon joined her elder sister Florrie as an untrained juvenile singer, dancer and comic, spending every summer with their father's minstrel troupe based on the sands at New Brighton, and every winter travelling on a horse-drawn cart as part of the King family act, pitching a tent whenever and wherever it seemed vaguely suitable and performing in and around various northern city centres.

After showing some initial promise as an imitator of others, Winifred was handed plenty of character parts for sketches and songs, playing Irish tramps, Italian waiters, haughty policemen, Lancastrian clog dancers and red-nosed Cockney clowns, as well as impersonating some of the well-known comedy stars of the era. It did not matter what their gender was, what their age was, what their personality was - whatever, thanks to her childish charm, got a good reaction, was promptly added to her repertoire.

It soon became clear to her instinctively pragmatic father that she, of all the family, possessed the kind and quality of talent that could really make the family some money, so he started putting her in talent contests under the new, more exotic-sounding, stage name of 'Hetty Volta', and stood back to watch what sort of impact she could make. Much to his excitement, she proceeded to do very well.

She started winning these competitions, and her father made sure that, in every sense, he got in on the act. If she won any money, it was added to the King family funds, and if she was awarded a theatre appearance, all of the other members of the King family, after his intervention, were given one, too.

She won a singing competition in Blackpool, for example, which had, as its prize, an engagement at the local Wellington Hotel. Her father stepped in straight away and ensured that the whole family got the gig. More successes followed, with the rest of the Kings clinging on for the ride.

Eventually, however, she got the chance to break away and go solo. At the start of 1896, a northern producer called J. Pitt-Hardacre, who was the current proprietor of the Comedy Theatre in Manchester, was urged by one of his assistants, E.V. Campbell, to go and watch a performance she was about to give at yet another local talent show (the young girl was, the excited assistant insisted, 'the finest mimic I have ever seen'). Curious to see what the fuss was about, Pitt-Hardacre did so, saw her once again win the contest, and decided to add her immediately to the pantomime - Cinderella - that was already up and running at his venue.

Several new minor characters and fresh bits of business were promptly devised expressly for her, and, on 25th of January, at the age of twelve, she made her formal professional debut on the stage. The impact was immediate.

In a review published a few days later, on the 28th, it was said of her:

She certainly possesses remarkable powers of mimicry. Appearing on the stage for the first time on Saturday afternoon she gave imitations of a number of well-known concert hall artists in a manner which elicited the heartiest plaudits. She has a pleasing voice, and she dances a hornpipe and an Irish jig very tastefully. At the performances yesterday she was repeatedly encored.

She soon went on to attract even greater praise when, at a moment's notice, she was promoted to the starring role in the panto after Gracie Leigh, the actor playing Cinderella, suddenly became indisposed. 'Every movement, every gesture, the songs and dances of Miss Leigh, were copied to perfection,' reported one critic, 'and the little girl who is not yet thirteen years of age received a perfect ovation. Mr Hardacre has indeed in her found a treasure.'

The producer certainly knew it. Pushing her father politely, but firmly, aside (after agreeing to pay him, for the employment of his daughter, £3 per month), Pitt-Hardacre proceeded to take charge of Hetty's career, changing her name to Hetty King (because, he said, 'Hetty Volta' sounded 'more like a troupe of acrobats'), putting her under contract for a three-year period and promoting her as his personal 'discovery' while placing her in a succession of his new revues.

His quasi-paternal care would also see him ensure that, as she was still unable to read and write, she went for lessons at a local school, and was also given some clothes for off-stage wear along with her own room at his home and the provision of daily meals. There was, in addition, plenty of training provided for her stage skills, which were already, quite naturally, developing at a rapid rate.

It appears, however, that her precociousness aroused a certain amount of envy among some of the longer-serving members of his cast and crew, and, as the months went on and Hetty continued to be singled out in the papers for praise, the tensions within the company grew worse. Things eventually came to a head in March of 1897, when an incident backstage saw all the key participants end up in court.

It seems that Kate Denby, the manageress of the Comedy Theatre, complained to Hetty about the lack of care she was showing towards her clothes (as well as the lack of respect she was displaying to Denby). Hetty's response to being admonished was deemed to have been unduly disrespectful, and, according to Denby herself, the manageress raised her voice in anger, or, according to Hetty's rival account, she squeezed her by the arms and shook her. What no one would deny is that Hetty, as a consequence, ran off to her parents' nearby caravan and claimed that she had been badly mistreated.

This prompted her father to march into the theatre and start accusing Pitt-Hardacre of allowing harm to come to Hetty. Pitt-Hardacre, in turn, threw the man, who was not only showing signs of drunkenness as well as a desire for violence, but was also making various legal threats, straight back out of his premises. King Snr then went to the police and demanded that both Denby and Pitt-Hardacre be charged with assault.

The case was ruled in the theatre owner's favour, with several witnesses contradicting the claims of assault. King's real motivation for initiating the proceedings, it was judged, was to get Hetty's contract cancelled so that he might benefit from her subsequent engagements far more than he currently did. The damage, however, had been done as far as her association with the theatre was concerned, and her stay there came to a sudden end.

Pitt-Hardacre, perhaps fearing more threatening interventions, declared that it would not be possible for 'amicable relations' between him and Hetty to be resumed, because, he lamented, 'the girl was not amenable to discipline'. She had the talent, he acknowledged, that suggested, with the right tuition, she might 'in all probability become a very great artist indeed', but, he added, it would not - could not - not happen with him. The contract was thus cancelled with immediate effect, and Hetty's career, after just one year as a professional, seemed in crisis.

She recovered, however, quickly enough, and, supported by another, younger, sister, Olive (who would remain her loyal assistant for the rest of her life), she fought on and found more work. So positive had been her notices while working for Pitt-Hardacre that, in spite of their recent legal difficulties, she was soon receiving offers of more attractive engagements from other producers, and by the second half of the year she was back on the major music hall circuit, making more money than she (or the rest of her now-heavily-dependent family) had ever dreamed of being able to command. The only frustrating thing, as the positive reviews continued to come in, was that, although she was being celebrated for her versatility and mimicry, she knew that, to become a bona fide star, she needed to be recognised for the singularity of her image.

It was this craving for something distinctive that led her to reflect on the range of characterisations that she performed, and ponder the potential of each one, or each type, to be made into something more special for her and her alone. Eventually, as she sifted through the options, she realised that, of all of her current personae, it was her occasional and usually very brief impersonations of men that often tended to make the biggest impact.

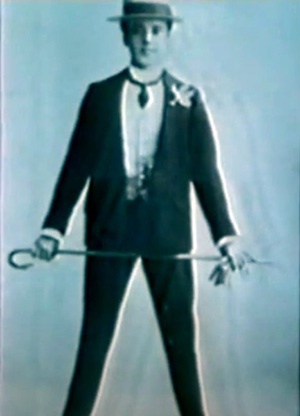

Sensing the scope for further comic specialisation, she went off to a department store - Holloway's in Manchester's Oxford Road - and spent an entire month's salary on a collection of smart clothes designed for a man (the money wasn't anywhere near enough, in fact, but she managed to persuade them to take payments 'a bit at a time' over the next few months). Standing in front of a full-length mirror in her digs, she studied the effect of various poses and gestures, tried out different wigs and fake moustaches, compared two or three voices, fiddled repeatedly with her hair ('My hair,' she would complain, 'was always - always - the biggest problem'), and, slowly but surely, she came up with a character - 'a swell' - with which she felt most comfortable as her signature role.

The following week, at the theatre where she was next booked, her first really substantial routine as a man proved captivating to the assembled crowd. What she went on to the stage and did simply astonished them.

It was quite a different spectacle to what they were accustomed. This was not just some light-hearted novelty act. This was something deeper, something smarter, something far more meaningful.

She was elegant, assured, intelligent and engaging. She not only looked the part; she also looked at the part - she played with it, taking it apart, toying with it, laughing at it, and then, with a nod and a wink, putting it back together again. She looked like a man, and she showed what men were, or could be, like. At the end, removing her top hat and bowing to the sound of all the applause, she knew that she had triumphed, and she knew that she could do it even better, in so many ways, from this point on.

In the audience that night was the northern theatrical producer John Hart, who raced backstage and not only congratulated her but also promised her a three-year contract right then and there. She was going to get £6 a week (about £900 in today's value), she was going to get star billing and she was going to be promoted as one of the most important performers in contemporary comedy ('No one was more surprised than me when this happened,' she later reflected modestly. 'A good fairy was with me').

Emboldened by this initial impact, she went on to develop a whole repertoire of male characters for her new act. Aside from the elegant toff, there would be round-tummied captains of industry, monocled military men, wise old country gents, and, especially, a range of hardy sailors, moving from the stiff naval officer to the saucy seaman - the latter featuring what would become her most famous song, Ship Ahoy! (All The Nice Girls Love A Sailor).

News of her novelty and rare quality spread rapidly via reviews and word of mouth, and it was not long before Hetty King was one of the best-known and best-liked comic performers in the business. As a new century dawned, so, too, did her stardom extend.

In 1901 she married Ernie Lotinga, a slapstick-style comic performer, and he now became her manager while continuing with his own solo act. They played the music halls of Britain together, and then she started touring the wider world: she visited Australia, New Zealand, the Far East and South Africa, winning an increasingly large mass of fans as she conquered each country.

Then came the United States: the scene of her greatest triumphs. She went there first in 1908, and during this and, increasingly, subsequent visits there she would be hailed as 'the greatest of all male impersonators' as well as 'the most popular single act in vaudeville today', and was also celebrated more widely for doing 'more to unite the English-speaking races in brotherhood than a disarmament conference'.

No entertainer, in the whole of the United Kingdom, was more widely, or more warmly, embraced during this time. Hetty King commanded every crowd that was around.

She remained with Ernie Lotinga until 1917, when he divorced her on the grounds of her adultery with the urbane American crooner Jack Norworth. She married again the following year, not to Norworth but rather to Alexander Lamond, a captain in the York and Lancaster regiment. He eventually became her agent, overseeing her increasingly busy international schedule, but in 1927, while she was away touring once again in South Africa (one of her favourite locations), she divorced him on the grounds of his adultery.

There would be more close personal relationships after that, but no more marriages. She preferred her freedom to withdraw and rest whenever she wanted, immerse herself in further research for her ongoing characterisations, and take whatever work whenever and wherever she wanted.

She continued touring during wartime, now sporting on stage, with her trademark attention to authenticity, a new battledress uniform and updated military references. Performing for the troops both at home and abroad, her act was carefully modulated so as to respect the necessary martial spirit of the moment while still teasing some of the more mundane aspects of masculine habits. The warmth of her wit, and the playfulness of each persona, endeared her to those eager for the brief distraction of some refreshingly harmless sanity.

Once peace returned, she began to concentrate her domestic appearances increasingly in the north of England, not only because she instinctively preferred that part of the country, but also, more poignantly and pragmatically, since so many of her favourite old London venues were now closing down, the best bookings were now coming, in niche markets, from elsewhere. Although she tried her best to keep her act looking up-to-date, much of her work was thus increasingly taken up with variety nostalgia tours with names such as Thanks For The Memory, Olde Tyme Music Hall and The Good Old Days.

The younger generation of comedians, however, would still flock to see her perform, marvelling at her image, her stagecraft and her always well-timed wit. Roy Hudd, who as a child was taken to see her by his grandmother, would tell me: 'I didn't even know she was a woman pretending to be a man. I just thought she was a really, really, funny performer. At the end, I turned to my gran and said, "Who was he?" And she said, "That was Hetty King." I just nodded, still a bit confused, but I knew I'd been in the presence of a true great'.

What, then, made Hetty King so impressive as a performer? One element was her exceptional attention to detail.

It had started when she just a young girl, passing the time on the streets, as a simple curiosity to learn about, and understand, other people, both in their particularities and generalities, and in the unique mix of the two that made each of them an individual. She was a natural mimic, whose every impression of other people - every sight and sound - stayed sharp and vivid in her memory. Once she was working on the stage, and sometimes playing male characters, she wanted the men in the audience to recognise themselves in her portrayals, so she made sure that each and every aspect was rooted in real life.

'I would follow a navvy, a builder, a soldier or a sailor and watch until they did something,' she later recalled. 'Then I would go off and put that into my act. I always could see something to study in a man.'

She was meticulous in the way that she would piece together each persona for the stage. She would always ensure, for example, that she had the right make of shoe, used the right boot polish, hair cream and precisely-matched fake hair; had a certain number of matches in her pocket to light 'his' pipe (which she would really proceed to smoke) and the right make of cigars and cigarettes; and would have a large mirror in the wings so that, just before each entrance, she could see that the clothes, posture, make-up and movement were exactly as they needed it to be.

If she was going to do a traditional Lancashire clog dance she would wear proper old leather and wooden clogs. If she was playing a sailor she would puff away on authentically strong navy 'baccy'. When she was planning to do a routine as a Grenadier Guard she not only spent several weeks watching them parading outside of Buckingham Palace but also persuaded one of them to teach her exactly how to shoulder arms and march.

She mastered each exercise so well that, at a barracks near the theatre at which she was appearing, an exasperated sergeant-major was reported to have barked at an especially inept group of new recruits: 'I can't do anything with you - you'd better all go to the Empire tonight and see Hetty King. She'll teach you more about the handling of a rifle in ten minutes than I could teach you in ten years!'

Nothing would ever defeat her pursuit of further definitive details about, as she put it, 'the man in the street'. On one occasion, when she boarded a ship docked at Bristol 'to have a look at the boys and just study a bit', but found that, in the presence of her as a woman, the sailors 'just dried up', she left and then returned wearing one of her stage suits. 'And instead of trying to be a little lady, I just became one of the boys. "Hello, boys," I said. And they came out and started talking to me':

Then a fellow came up from down below, all grease and that sort of stuff, and I watched him filling his pipe. The loveliest part of it was that he took out of his pocket a piece of thick twist. Well, of course, I was in my glory watching this: he was cutting it here and cutting it there. And that's the sailor I copied - and still copy - in my act.

It was the same with her study of men smoking. 'You take a cigarette,' she would explain, 'and one man will suck on it, and then sort of twist it around in his mouth with his fingers and then spit it out the side, you know, while another will puff and then sort of hold it out and flick it with his thumb, another will tap it more delicately with his little finger-tip, another will do it with his index finger, and so all of these little differences will help define the different characters.'

Another factor that made her so compelling was that she seemed able to channel a spirit as well as capture a look. There was always a personality to go with the pose.

'My work is in characters,' she was always pleased and proud to confirm. 'I am evidently like some mother's son, some lady's husband, or brother, because I hear these comments - "Oh, isn't that just like our Tom" or "our Bill".'

She came to know each character so well that she could ad-lib whenever she wanted and still seem true to the individual she was inhabiting. It never seemed merely like some kind of trick or turn with her; she flicked away the quotation marks just as effortlessly as the ash from her cigarette.

A third ingredient was her crafty critique of masculinity. There had been plenty of male impersonators before her in music hall history (most notably Vesta Tilley), and several others were her own contemporaries, but she was now adding something different, and deeper, to that dramatic tradition.

The conventional approach had been merely to be a woman dressed as a man. The incongruity (a woman clearly trying and deliberately failing to be taken for a man) or the efficacy (a woman succeeding at being taken for a man) was, before Hetty King, the comic conceit. This, however, was something different. In this approach to cross-dressing, the commentary (a woman succeeding in being taken for a man in order to better mock the man) was the conceit.

Hetty King dressed up as a man partly to show that dressing up as a man was always essentially an act - for men as well as women. She was not laughed at because she was a woman pretending to be a man; she was laughed at because she was playing a man pretending to be a man.

She smuggled herself into the common view of masculinity and then demonstrated from the inside just how silly much of that model really was, and always is. It was the fact that she made her men so believable that enabled her, in turn, to make their silliness all-too believable as well.

The comic impact, as a consequence, was much more complicated than ordinary cross-dressing acts, and, because of that, much more engrossing and enjoyable. It was never the kind of mockery that was cruel or dismissive, and so men laughed as well as women, but it was often so sharply perceptive (such as when 'he' proudly rolled a cigarette with one hand and then looked out in anticipation of the awe this childishly trivial trick was supposed to elicit) that it caused a few to squirm a little in their seats with self-consciousness.

Hetty King, in sum, elevated the activity of cross-dressing, in a critical as well as comic sense, to the status of an art. 'A professional to the core,' one admiring critic commented, 'it is Miss King's genuineness and perfectionism which emerge in every word and action.' Another wrote: 'Whatever she does is finished and polished to the last degree, and yet never for a moment is the essential humanity lost.' 'You are not falling for a disguise,' noted a third. 'You are appreciating fine acting.'

She would continue to perform, in spite of progressively failing health (navigating the backstage stairs and walkways of cold and dimly-lit old theatres, there were falls, broken bones, and bouts of bronchitis), right up to the end. Whatever setback she suffered, she shook it off and struggled on.

Always happy to help and advise up-and-coming entertainers, they, in turn, never hesitated to line-up, listen to, and learn from her. The crooner Frankie Vaughan, for example, was taught by her, with all the kicks and sticks, what became his trademark Give Me The Moonlight routine; the camp comic Larry Grayson was coached by her on how to time a line, use a prop and command a crowd; and countless young cross-dressing performers, male and female alike, relied on, and worshipped, her as their mentor.

'Consider this,' said her friend and, in later years, occasional co-star, Sandy Powell. 'Most elderly stars [...] played their own age as they got older. But Hetty goes on every night and plays sailors, bridegrooms, men-about-town. And the miracle is that she is completely believable in these roles. We love her very much.'

In a profile by The Times newspaper in 1969, still in the midst of her usual summer season, it was remarked how she remained a stickler for standards, still looking for new details and fresh insights (no smartly-dressed man ever left her presence without first being pressed for the name of his tailor), still driving herself on (and still proving so popular with audiences that her current engagement, at the Hippodrome Theatre in Eastbourne, had been extended to three further weeks). 'At eighty-six,' it was said, 'she still acts at a pace and with a grace which many women half her age would envy.'

'Off stage,' wrote another journalist at the time in The Guardian, marvelling at the length and depth of her career, 'there is about her an aura of champagne and sovereigns, of gas lights, of horses clopping through the London fog. She is a beautiful and happy old lady and her eyes (to misquote Keats) "mid many wrinkles, her eyes, her ancient, glittering eyes are gay".'

She died at Wimbledon Hospital on 28th September 1972, aged eighty-nine, having recently been suffering from pneumonia, after working for more than eighty years in the entertainment business without a break, and just two days after she had signed a contract with the BBC to appear in yet another show. She was given a full and heartfelt farewell the following month, in a chapel packed with her fellow professionals, at Golders Green Crematorium.

The sense of loss was felt both widely and keenly in all show business circles. The Stage trade paper, in a particularly emotional appraisal, reacted to her passing by calling her 'the last of the immortals', and declaring that, now that she was gone, 'the music hall is dead'.

The great American star Buster Keaton, who toured with her in the early 1950s, was so impressed by her performances that he always told all of his colleagues, on both sides of the Atlantic, that 'Hetty King is the real tops in my book'. That, really, is how highly she was rated, and how much she meant.

It is now almost ridiculously easy, of course, in the attempt to praise past performers, to stride straight into the trap left lurking there, by the likes of good old Tommy Cockles of The Fast Show, and seem like some trivial spectacles-adjusting twit twittering on about some ancient and justly-forgotten fool such as Arthur ('Where's me washboard?') Atkinson (how oddly, and sadly, revealing, about certain classes and cultures, that we, or at least they, find mocking those who used to entertain people so much easier than we, or they, do those people who used to rule over them), and talk away into the airy indifference of today. There were some performers, however, who simply didn't - and still don't - deserve such smugly ignorant indifference.

Hetty King liked to say that, in her own eyes, she was 'just a pro', but, in the eyes of all those who witnessed her skill and style, she was so much more than that. A key contributor to the empowerment and advancement of women in comedy, she is, in these days of debates about gender fluidity, ripe for a revival of interest and appreciation, as well as richly deserving, in the broader terms of comic history, much greater prominence and respect.

All the nice girls loved Hetty, and all the nice boys ought to, too.

A 1970 documentary, Hetty King: Performer can be watched on YouTube in three parts:

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more