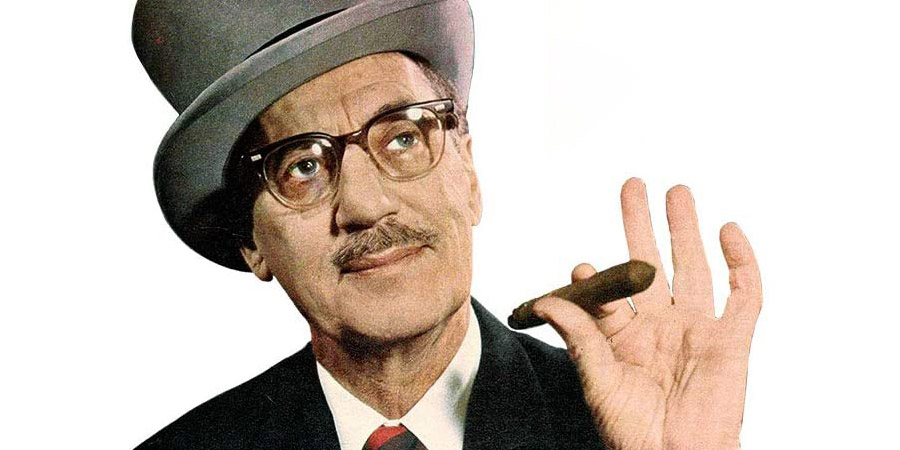

Hello, I must be going: Groucho Marx on British TV

'I've got to stay here,' snaps Groucho, as Professor Wagstaff, in the Marx Brothers movie Horse Feathers (1932), 'but there's no reason why you folks shouldn't go out into the lobby until this thing blows over.' He must have been tempted to make a similar announcement when, more than thirty years later, he found himself trapped in his first and only British TV series.

Called Groucho, it started in 1965, ended in 1965, and then disappeared quickly into obscurity. One might have thought, given the legendary status of the star and the uniqueness of this British adventure, that some reasonably substantial account of the series would have been compiled and preserved for the sake of posterity, but no: the impression one gets is that most of the facts, like most of the footage, are missing believed wiped.

The vast majority of the Marx biographies, especially the ones written by his fellow Americans, barely acknowledge this peculiar episode in his long and otherwise illustrious career, while what little is logged about the series online is often not even that informative, or accurate, about the basic programme details (the IMDb entry, for instance, currently contains barely anything beyond the broadcast year and the date of one of the two episodes known to have survived, while Wikipedia, at the time of writing, has not even awarded the show its own error-ridden page).

This is all quite odd, because, if one knows where to seek them out, there are actually enough fragments of information and insight about the show, from those who made it or saw it, to piece together a fairly vivid picture of what really happened and why it went wrong. What follows, therefore, is the story of how and why Groucho Marx's time in Britain proved so brief and disappointing.

It begins with the end of his US TV show You Bet Your Life. A light-hearted quiz series, it had given him a new lease of life after the decline of the Marx Brothers' movie career, providing him with a solo vehicle, first on radio and then network TV, which allowed him to adopt a more 'natural' and avuncular persona and appeal to a broader family audience.

He would sit down on a stool, puffing away on his cigar, and welcome ordinary members of the public to come up on stage, chat about themselves, and answer a series of questions to compete for cash prizes. It was simple, informal, undemanding and entertaining: his razor-sharp ad-libs continued to appeal to his old fan base, while his ability to establish an effective rapport with guests who were shy, awkward or sometimes downright eccentric won over many of those viewers (particularly in the more conservative Midwest) who had previously thought of him as far too prickly and acerbic.

Running all the way from 1947 to 1961, it was a hugely popular show - regularly drawing audiences of 22m, and peaking eventually in the ratings as the third most-watched show in the country - and it only started to fall slowly out of fashion and favour in the final three of its fourteen seasons. Groucho, who basked in the warm glow of its success, came to convince himself that it was the best thing he had ever done.

The cancellation, when it came, thus left him deflated and depressed. 'At the moment,' he told reporters glumly, 'I'm a bum.' He was seventy now, and it must have felt as though his career was in danger of crumbing away.

An attempt at an unofficial revival - Tell It To Groucho (1962) - on a rival channel only lasted a few months, and, aside from the odd guest appearance in other stars' shows, the only notable exposure he had on TV during the next couple of years was as an actor in a one-off production of his own summer stock stage play, Time For Elizabeth. It therefore came as a welcome and timely surprise when, in the summer of 1964, an offer of work arrived from England.

It came from Elkan Allan, the ambitious Head of Light Entertainment at Associated-Rediffusion (the ITV franchise holder for London and parts of the surrounding counties), who, aside from being an avid Marx Brothers fan, had calculated that the stature of a world famous star such as Groucho would lend the channel (which had recently rebranded itself as 'Rediffusion London' and started striving for a more fashionable 'Swinging Sixties' style of image) some much-needed lustre. Signing a figure so beloved by middle-aged viewers, he reasoned, would also help to counter-balance the growing number of youth-oriented shows, such as Ready Steady Go!, which he had been commissioning. It seemed the right move at the right time.

Groucho Marx, it appears, felt much the same. Already quite an Anglophile, the prospect of him and his family spending a period of time living together in a smart part of London certainly held some appeal, as did the notion of starring in a hit series in another country (and thus showing American TV bosses what they were missing). The specific nature of this new project was not yet known, but, whatever it was, he was not against it.

He called his old You Bet Your Life senior director, Robert Dwan, and asked him to join him in England as the show's producer. Dwan, once Groucho had consented to him recruiting their mutual friend and colleague Bernie Smith as his partner, agreed.

Dwan and Smith (who not only thought quite alike but also, with their dark receding hair, serious expressions and sober dress sense, looked quite alike) then met to discuss what kind of show they could and should bid to produce. Neither man felt that their star, at this stage in his life and career, had either the appetite or the aptitude to get used to a completely new kind of format (he was already semi-reliant on cue cards and other forms of hidden help), and so they settled instead on simply adapting the tried and trusted You Bet Your Life formula for a brand new British audience. Elkan Allan was quick to concur - his channel was already something of a home for popular quiz and game shows (including Double Your Money, Don't Say A Word and Take Your Pick!, as well as The Celebrity Game, on which Groucho had made his first and so far only appearance on British TV a few weeks before) - and so work began in earnest.

Bernie Smith was the first to fly over to London, in February 1965, in order to start planning discussions with Allan, who had appointed himself executive producer of the project. Dwan, meanwhile, stayed behind to deal with a few rights-related issues, amongst other business, before joining his partner a couple of weeks later.

When he did finally arrive, touching down at Heathrow airport, he felt full of enthusiasm for this new adventure. They were, after all, basically importing a vehicle that had delighted American audiences for more than a decade, and they were now being backed by a British team who were clearly thrilled to be working with such a venerable comedy legend. All the portents, he reasoned, were positive.

As soon as he stepped out on to British soil, however, he was rudely disabused of such optimistic expectations. A bleak-faced Bernie Smith, who was there to greet him, walked over and, rather than shaking his partner's hand, simply gripped it tightly, looked him solemnly in the eye and said: 'Go home'.

We know what happened next, and for the rest of the team's time in London, thanks in part to the fact that Dwan, a very meticulous man, kept detailed notes about the production, which he would draw upon in his later memoir, As Long As They're Laughing.

Smith took Dwan to their temporary offices at Television House on Kingsway, where he proceeded to relate to his partner all of the concerns he had acquired since arriving a few weeks earlier. Having now watched British TV for a while, he said, he feared that their show was going to seem far too pedestrian and conservative, and he was not at all sure that Groucho's style of humour was going to work on the contestants, or that the contestants were going to make much sense to Groucho. They had, in short, seriously underestimated how much of a culture clash there was going to be.

Dwan listened carefully, but, being used to Smith's tendency to err on the side of negativity, refused to be so pessimistic. He would explore the issues himself, he said, and, if there were indeed any serious problems, then together they would work out a constructive response. In the meantime, he stressed, the preparations had to go on, and they needed to project an air of positivity as they collaborated with their British colleagues. Smith, though still anxious, agreed, and the work went on.

They managed, by the start of April, to have a summary of the show ready for a press release. It announced that the series - provisionally entitled Grouch - would consist of thirteen episodes, and feature the star responding to what the contestants told him about themselves: 'their occupations, marriages and idiosyncrasies'. The sort of people he might meet 'could range from a barrow boy in Covent Garden or a fisherman from Grimsby to a Bond Street tailor or a fashion model'.

Two pairs of guests either side of the commercial break would come on stage and chat to Groucho. The comedy aspect would come from his witty conversations with these people, who would relax in his company and inspire him to make jokes about British life, labour, leisure and language.

The quiz segment of the show was set to be, initially, 'The Hat Game', which would see two guests pair up to answer general knowledge questions, splitting any money they might win up to the strangely specific sum of '£244'. They would proceed by picking four envelopes from a bowler hat, containing questions ranging in value from £1 to £25. If three or more questions were answered correctly, the contestants would go on to the climax of the show, called 'The Topper' - which saw a top hat brought on, containing three more envelopes, with questions ranging from £50 to £150 in value.

The bouffant-haired disc jockey and TV presenter Keith Fordyce had been chosen to serve as the British equivalent of George Fenneman, Groucho's long-standing announcer and good-humoured sidekick from You Bet Your Life. Just as the unfailingly amiable Fenneman had been expected to bring on and introduce guests, organise and explain quizzes, cue a sequence of jokes and also accept whatever ad-libbed insults were aimed in his direction, so too was Fordyce supposed to serve as an all-purpose servant and stooge, as well as having special duties explaining any British terms or customs that Groucho might otherwise not understand.

Now that the media had been briefed, the focus moved on to writing and recruitment. As far as the writing was concerned, both Dwan and Smith (who had served as head writer on You Bet Your Life) realised that they would have to assemble a team of experienced British gag writers who could provide Groucho with enough suitable retorts to whatever the guests might - in accordance with their pre-show interviews - say on the night. The best specialist agencies, such as the Spike Milligan, Eric Sykes and Galton & Simpson-owned company Associated London Scripts, were thus deluged with requests for the best available writers to turn up, read the raw material and then offer Groucho some comic options.

The search for interviewees was just as rapid. A young researcher named Sandy Faulkes was dispatched to various cities all over the United Kingdom, seeking out potential contestants. Pubs were probed, department stores explored and local modelling and talent agents tapped as the search went on for suitable 'characters'. The aim was to select a good enough mix of old, young and middle aged, and quirkily introverted and entertainingly extroverted, to sustain the whole of the series. A range of public figures were also sounded out in the hope that the odd grandee might grace the show with their presence. Things were getting busy.

The momentum was further increased when Groucho Marx and family finally flew in late in April, having found a very attractive apartment in Mayfair next door to their friend Gregory Peck (who was in the country to start filming the movie Arabesque). As far as Marx was aware - Dwan and Smith having kept him blissfully ignorant of all their anxieties - the production had been progressing smoothly in his absence, and his mood was further buoyed on arrival by an invitation that was waiting for him to take part in a prestigious 'Homage to T.S. Eliot' - one of his literary heroes - later in the summer at the Globe.

The one issue that the producers did feel obliged to discuss with him concerned what they regarded as the 'raciness' of British TV. They thus sat the star down and told him how startled they had been, coming from a far more prudish and circumspect broadcasting culture, at how much more open and daring and sometimes downright outrageous the output could be on British screens.

Groucho, initially, laughed off their claims as a wild over-reaction, but, after he had watched a number of the shows they had chosen to illustrate their point, he, too, was surprised and somewhat disoriented. After years in America of pushing against the censors, he now found himself in Britain with, apparently, no censors to push against, and, he realised, if he tried to push against something that was no longer there, he was likely to fall down flat on his face.

The trio expressed their sense of shock, like panting explorers sending out a message from deep inside an exotic jungle, to a reporter from the San Francisco Examiner. Dwan, for example, said that he had been so stunned by some of the words and phrases he had heard during prime time on British TV that he had quickly scribbled them down so as to prove to himself and others that he had not merely imagined them. 'Groucho can get pretty racy,' he acknowledged. 'He knows all the jokes. But the raciness over here is way beyond him.'

The star himself, while agreeing with Dwan, sounded more ambivalent about the situation. Yes, he said, it was a shock at first, 'but I'm beginning to have quite a time. It's new to me to say anything I want. They have a much franker recognition of sex as a fact of life. You can get instant laughter if you start a story with a double meaning.'

The problem was that none of them were certain whether to stick or to twist. If they tried to ignore the greater freedom, they feared, they would end up looking and sounding painfully old-fashioned, but if they tried to embrace it, the danger was that Groucho, at seventy-four, would end up looking and sounding like a dirty old man. So they neither stuck nor twisted. They fudged.

They decided to trust the British writing team to write the kind of gags that sounded tamely à la mode, while urging Groucho to strongly resist the temptation to ad-lib the kind of line that he knew would have been censored back in the US. Although it was a compromise that made sense to them all at the time, it would, in retrospect, come to seem like one of the factors that ended up making the show so flawed.

Successful productions know what they are striving to achieve. Unsuccessful ones merely know what they are striving to avoid. This production kept getting itself stuck somewhere in the middle.

Groucho himself, however, remained in a relaxed and confident mood as the recording sessions drew near. Puffing away on one of his trademark cigars, he joked with reporters, telling them that not only did he have no idea what 'Rediffusion' meant but it had also taken him four weeks just to learn how to pronounce it, and assuring them that he was simply content still to be working in the 'only business where a guy can sleep until noon'. As for the forthcoming series, he merely laughed and said that, once the first programme goes out on air, 'we may leave town the next day'.

When filming of the show (now officially called Groucho) commenced at Rediffusion Studios in Wembley Park, however, even the star was starting to worry. He had agreed with Dwan and Smith to use the same warm-up technique that he had used to great effect throughout all the years he had been on You Bet Your Life. It consisted of him walking on to the stage, welcoming the audience and then, as he sat on his stool, telling them - every time - the following monologue:

There are all kinds of snobs in the world. There are social snobs and financial snobs and family snobs. And there are also joke snobs. You can tell someone a joke, and if they've heard it before, they point a finger at you accusingly, as if you were a criminal. For example, this is a joke that is at least fifty years old and that most of you, I'm sure, haven't heard. A fat woman walks into a drugstore and says to the clerk, 'I'd like 10 cents worth of chafing powder'. The druggist says, 'Walk this way'. And she says, 'If I could walk that way, I wouldn't need the chafing powder'.

The point of it was to encourage the audience to laugh without any inhibition, and it always worked. In England, however, before that first recording, it did not. It fell horribly flat.

A deflated Marx withdrew backstage, where a hurried inquest was held. 'He was greatly disturbed when it was explained to him by our British director that it was probably a matter of semantics,' Robert Dwan would recall. 'It is not a drugstore in Britain, but a pharmacy, and the analgesic is not called chafing powder.'

It was a moment when all of the Americans looked at each other and realised that, in spite of their best efforts so far, they were still ill-prepared to cope in this new comic context. 'It was one of the steps in our gradual realisation,' Dwan would reflect ruefully, 'that, although they seem to speak the same language in England, it is a foreign country.'

It was a blow that hit Groucho Marx the hardest, badly shaking his confidence right at the start of the series. 'In America,' Dwan noted, 'Groucho's familiarity with slang and idiomatic speech allowed him to play with speech patterns, to twist meanings, and probe for hidden clues. In Britain, although he thought he was speaking the mother tongue, he didn't have the lifetime of experience that helps supply all the hidden meanings and innuendoes. Those, after all, were his stock in trade, and he was impoverished without them.'

Some of these problems might have been overcome, or at least partly obscured, by the star relying more on the material he was being given by his team of British gag writers, but he managed, unwittingly, to sabotage that solution by delivering it all so badly. 'He was just too lazy to learn his script,' one of the writers, Brad Ashton, would recall. 'He'd read it off this big screen that was positioned behind the backs of the contestants. He'd squint at it, look at it slightly too late, stumble over some of the words. Loads of really good, really funny lines had to be cut because he loused them up.'

The recordings went on, therefore, with a star who was clearly not at his best, and a succession of frustratingly reticent and reserved guests, and a production team whose spirits were starting to sag. It was an increasingly careworn Dwan, therefore, who sat down and wrote a letter to his family back in America, detailing some of the drama:

Bernie is experiencing all sorts of difficulties in finding contestants. British people don't want to reveal their private lives on the 'telly' and it isn't considered comical to have someone prying into their affairs. We've had particular difficulties with members of the upper classes, and especially, of course, with the aristocracy. We did manage to get the noted author, Lady Antonia Fraser, because, I suppose, she had a book to publicize. She was charming and very bright. And we had a certain Lord Hertford, but that was it for the nobles. As for celebrities, we managed to get the well-known romance writer, Barbara Cartland, flamboyant as always, but, so far, no other notables. Several members of our production staff, including our director, saw four of our old US shows and didn't think they were funny at all.

Things improved somewhat as the sessions continued. Groucho, having had his morale massaged by his backstage team, grew slightly more assertive and ad-libbed a little more, and made more use of his new sidekick, Keith Fordyce, whenever any cultural confusions arose. He was further encouraged by the fact that the studio audience (which, in keeping with the British tradition of the time, had formerly been left in darkness) was now at least partially lit (as was the norm in America), so he could look out at them and feel more of a personal connection. There was also, apparently, a slightly better mix of contestants, each one of whom was now being briefed more carefully so as to interact with the host more effectively.

By the end of the thirteen recordings, therefore, the mood in the studio was considerably brighter. The feeling was that, after a decidedly shaky start, real progress had been made.

Privately, however, the two producers knew that, when the series was finally shown, there would be yet another problem to endure. That problem concerned audience expectations.

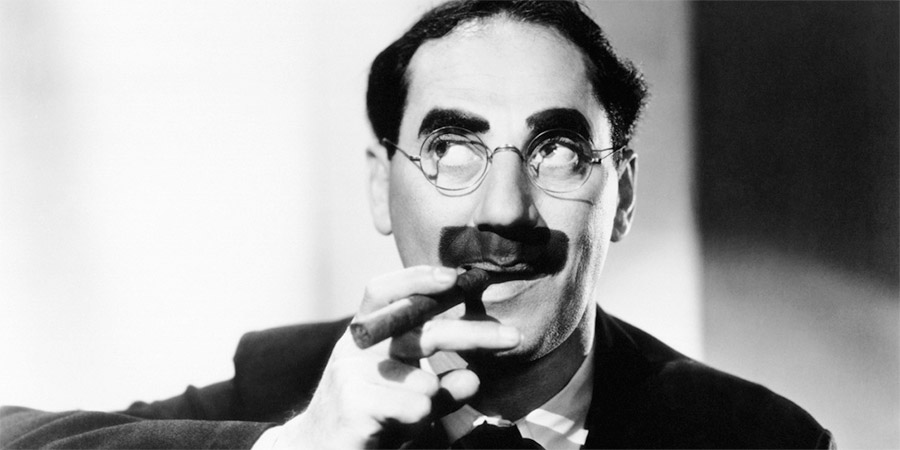

Dwan and Smith, like millions of other Americans, had seen Groucho evolve over many years from the dynamic figure of the Marx Brothers movies, loping and leering his way from one satirical scene to the next, to the sedate and rather vulnerable man who found a new home in television. It had been a gradual and natural transition.

Most British viewers, however, had not been exposed to the Marx of the past couple of decades. They were still watching re-runs on TV of the great old movies from the 1930s and 40s. It would prove quite a shock to some of them, therefore, when the energetic middle-aged man they had only seen on screen the other week, with his jet black hair and thick painted-on stripe of a moustache, suddenly reappeared on Rediffusion looking so much older, and frailer, and slower. Dwan and Smith could only brace themselves for the less-than-positive reaction.

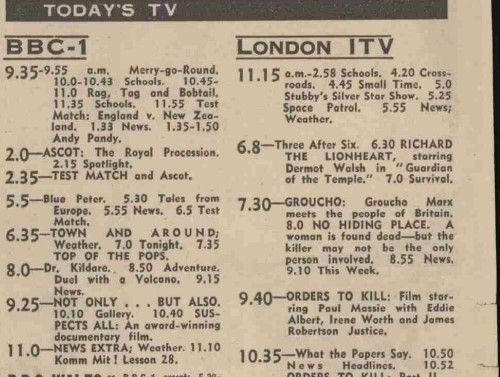

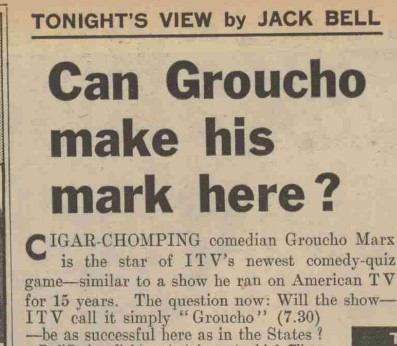

The first episode went out at 7:30pm on Thursday 17th June 1965. 'The mums and dads will love him,' Elkan Allan was quoted in the day's papers as saying. 'But I just don't know whether the young people will.' The fact, however, that it had been scheduled directly against what was probably the BBC's most popular youth-oriented show, Top Of The Pops, suggested that the ITV network schedulers had already made their minds up about that particular matter.

Some reviewers, judging by their comments the following morning, had already made their mind up about the show as a whole. Derek Malcolm, for example, writing in The Guardian, dismissed it as a disaster: 'One would not have thought it possible to devise a programme which could render Groucho Marx unfunny. But Robert Dwan and Bernie Smith have managed it with fearsome efficiency. [...] It was as much as even he, a member of at least one species of wit, could do to prevent himself drowning in the damp sea of mindlessness that engulfed the screen for what seemed an interminable half hour'. The Observer was equally damning, describing 'poor old Groucho Marx' as being 'trapped in the death grip of a British quiz show' that was 'dismal beyond belief'.

Dwan, after reading all of the responses, wrote another melancholic missive for his family in the States:

The reviews were exactly what we feared. Worse, really. They said all the things we hoped they wouldn't. Actually, so far, two have been very good, loved it, one has been neutral, and four are violent, just hated the whole thing. They thought it was silly and dull and disgraceful for the great man to be in it. Obviously, they expected Dr Hackenbush and didn't get him.

There was still, however, some cause for hope. He added:

I was sitting in a little French coffee shop in Soho at nine a.m. reading the reviews and getting ready to order hemlock, when a very distinguished-looking man across the way started telling his friends that he had seen a marvellous program last night, very funny. He started quoting some of the jokes, thought Groucho was wonderful, had great dignity. I went over and thanked him for saving my life.

Groucho himself, on the other hand, could not really see past what he regarded as the lazy and disingenuous complaints concerning how far, supposedly, he had fallen below the great achievements of his past. 'People can't seem to separate me from Dr Hackenbush or Capt. Spalding or any of the other film roles,' he grumbled to a reporter friend back in the US. 'I don't know what they expect me to do to them.'

As the series went on, however, the audience figures slowly rose (averaging about 3.7m, and peaking very briefly, for the fourth episode, at 4.5m - still fairly modest for the time, being at best the twentieth most-watched ITV show of the week, but nonetheless a step in the right direction), and the responses seemed to improve. Once both viewers and reviewers alike had recovered from the initial shock of not seeing the 'old Groucho', they started to warm, at least a little, to the 'new Groucho'.

Critically, the judgements would continue to cluster on the negative side of the spectrum, but at least some of them were softening their style of disapproval. The Observer, for example, described the second episode as 'several degrees less excruciating than the first', and then added: 'The frame will always be crippling, but this time, the veteran anarch, stimulated by a brighter quartet of public stooges, was distinctly more like his chaotic better self'. The Spectator was similarly striving to sound more polite, praising the show for 'the unselfishness with which it encouraged the participants'.

A few of the reviewers actually liked it. 'He has restored a touch of pristine polish to television's old stand-by, the quiz,' wrote one. 'Less gifted mortals would be unable to poke gentle fun at strangers without causing offence.'

There was still the odd complaint, and Marx's occasional lapses into his old habit of leering at female contestants who were young enough to be his grandchildren certainly provoked some understandable outbursts of indignation (e.g. 'I felt embarrassed for the woman of whom Groucho observed: "You have very pretty thighs, and I'm delighted to look at them"'). In general, however, the series managed, as it moved on to its conclusion on 9th September, to please a few more friends, and placate a few more foes.

When the thirteen week run was finally over, there was a sense more of relief than satisfaction among the production team. It had been a struggle, there had been a great deal of learning lessons 'on the hoof', and some of the critical attacks had hit home and hurt badly, but they had all survived it, and they were simply eager to move on to other adventures.

Elkan Allan filed the series away as an honourable failure and immersed himself in Associated-Rediffusion's new projects. All but two of the thirteen recordings, as far as we currently know, were either dumped in a skip or else erased to free up the film.

Dwan and Smith (both of whom had been particularly stung by some of the invective that had come their way) returned swiftly to the States with something of a bitter taste in their mouths, blocking out all of their own blunders in favour of blaming the British, petulantly and not particularly coherently, for finding Groucho 'not dirty enough for them', and for holding on to an outdated impression of the star: 'The audiences there obviously expected the glib, crouched-walking Groucho of Animal Crackers and A Night At The Opera,' Dwan would complain. 'They were not prepared for the more sedate, sedentary character of You Bet Your Life - more Julius than Dr Hackenbush.'

Smith sounded even more embittered. He would sneer that the show was only watched by 'a bunch of women who don't have any idea of what's going on', and who could only understand 'somebody getting hit over the head with a baseball bat or being tickled with a feather'.

Groucho himself, on the other hand, shook off the disappointment as though it was just a light dusting of snow on a winter coat. He remained too big a star, with too many other distractions, to bother himself by pondering any post mortems.

London still loved him, and, before he flew home, he relished mixing with some of England's great and good whom he had met at the commemorative T.S. Eliot event (where he read from Old Possum's Book Of Practical Cats), and he was genuinely touched by the long and loud standing ovation he received when he stepped on to the stage at the British Film Institute after a special showing of Animal Crackers.

There were no hard feelings on his part, nor on England's part. His brief spell on British television had indeed now blown over, and he was back to being the beloved Groucho of memory. That seemed to suit us, and, by this stage, it probably suited him, too.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more