The Trouble With Harry: The premature exit of Harry Green

It has long been common for comedians, after a bad experience out in the spotlight, to complain that they 'died' that night. One man who couldn't say that was Harry Green, for the sad and simple reason that he did indeed die that night.

It actually happened during a live television play, back in 1958. The play in question was called Poet's Corner, and it was going very well for Harry Green, and then, all of a sudden, it wasn't.

This Harry Green, by the way, wasn't the Harry Greene who featured on TV in the Fifties with his popular DIY show Handy Round The Home. This Harry Green was the Harry Green who featured on TV in the Fifties as a popular character actor.

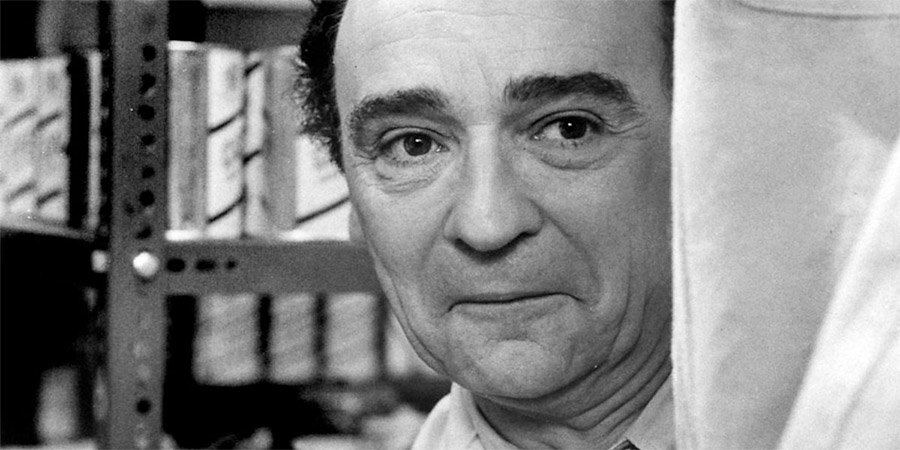

That Harry Green was aged sixty-six at the time of his unexpected demise. He had been working steadily as an entertainer for almost fifty years, first in America and then in England. He was a very familiar face on Britain's television and cinema screens, and a frequent contributor to comedy shows, plays and revues.

Born in New York in 1892, Green (his real name was Henry Blitzer) had studied and qualified as a lawyer before being distracted by the acting profession. Teaming up with an old friend, he toured the vaudeville circuit during the 1910s as part of the comedy double act Ross & Green, featuring a routine they called 'The Hebrew Jockey and the Sport'. He later went solo, performing a one-act satirical play called The Cherry Tree, in which he played a character named George Washington Cohen.

He made his first movie - a musical comedy, one of the first 'talkies' in fact, called Close Harmony - in 1929, and went on to appear in more than sixty Hollywood productions over the next three decades, specialising in playing stereotypical Jewish comic characters. Never anything more significant than a very reliable supporting actor, his short and portly build, pudgy lived-in face, warm and gravelly voice and engaging personality nonetheless kept him busy in a wide range of genres, playing everything from dutiful low-ranked gangsters to unthreatening friends of the leading men, and he was known as an easy-going and popular presence on the set.

A firm Anglophile, he started visiting Britain in the summer of 1914, making his London debut at the Empire Theatre in a revue called The Merry-Go-Round (playing a Jewish lawyer), and followed that, once the First World War was over, with numerous other appearances in some popular West End shows. By the mid-Forties he had settled comfortably in his adopted country with his wife Alva and their two children David and Roland, basing themselves at a very grand house - The Gabled Lodge - in Maidenhead, Berkshire, with five-and-a-half acres of surrounding land, a swimming pool, a putting green, a large room dedicated to a special collection of over five thousand antique intaglios [carved printing plates] and one of the largest privately-owned libraries of theatrical books in the country.

A smart investor and shrewd entrepreneur, he was now earning enough to send his sons to Harrow as well as open a glamorous nightclub in London's Brewer Street called The Jack of Clubs (which attracted plenty of publicity for featuring a 'Kiss Corner' where visiting female celebrities - Princess Margaret was one of the regulars - left their lipstick imprints on the wall). He was also sufficiently well-known and well-liked in show business circles to be invited to take part in the Royal Variety Performance of 1954.

Very busy in all of the available media as an all-purpose 'local' American, one of his favourite roles of the time was as Mr Perlmutter in the Jewish-themed comic play Potash And Perlmutter, in which he appeared several times in separate productions on both radio and television. He had also played 'Big Dutch' in the 1955 British-made film adaptation of Shakespeare's Macbeth, called Joe MacBeth - set in the 1930s American criminal underworld - and also had a minor role as a lawyer in Charlie Chaplin's 1957 movie A King In New York.

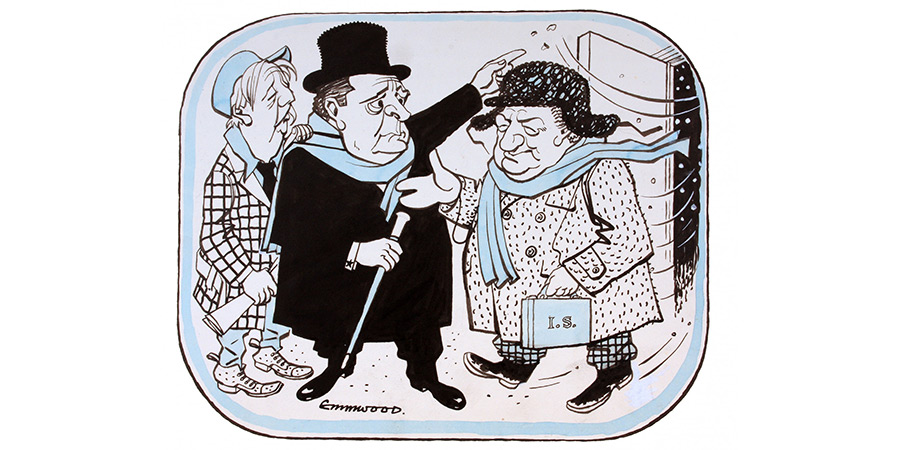

Another project of which he was particularly fond was Isidor Comes To Town, a 1954 comedy drama about antisemitism in a small English town that he adapted specially for television, and in which he co-starred with his daughter-in-law, Joan Rice. It won him some of his best reviews in recent years ('Mr Green is a personality who sweeps everything before him') and demonstrated his ability as a writer as well as a performer.

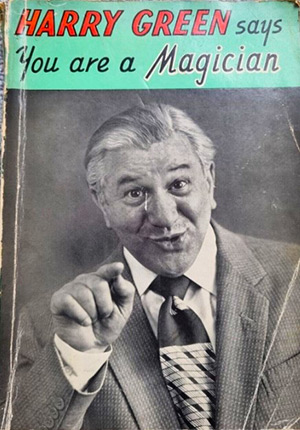

He was also a highly-skilled amateur magician, recognised by many professionals as being one of the most accomplished card manipulators currently active anywhere in the world. Always in demand for his conjuring act, he had performed his repertoire of tricks before countless distinguished audiences, including the British Royal Family and many other VIPs in various locations abroad (Prince Philip would make a point, every time that they met, to ask Green to teach him a new illusion: 'One that will really baffle the family'). He had even published a book on the subject - Harry Green Says You Are a Magician - whose preface had been written by the Duke of Gloucester.

Poet's Corner, his latest project, was a one-hour play - made by Associated-Rediffusion at its Wembley studios as an edition of its long-running ITV Television Playhouse network strand - which was due to be screened live at 9pm on the evening of Friday 30th May. Written by the Welsh playwright Gadfan Morris, it was billed as a light comedy about a young boxer who dreams of finding fame as a poet, but is forced to acquire it as a prize fighter instead.

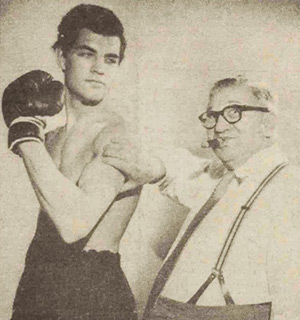

Harry Green was very much looking forward to appearing in Poet's Corner. His role as the cigar-chomping Mose, an outwardly tough but essentially tender-hearted Jewish-American boxing manager, had seemed tailor-made for him, because, many years earlier in his colourful life, he had actually been in that business himself.

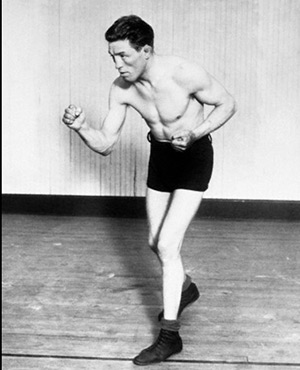

Back in the 1920s, during one of his many stays in the UK, he had co-owned the Manor Hall, Hackney, with Ted 'Kid' Lewis. Lewis was one of Britain's pre-eminent professional boxers of the era - a former British, European and World Welterweight Champion, and then British and European Middleweight Champion - who was starting to branch out into management as he looked to wind down his own fighting career.

Together they staged a succession of well-attended events at the Manor Hall, as well as arranged for the finding and training of up-and-coming prospects, and worked, at least for a while, at the centre of the local boxing scene. Ever-restless, however, Green soon moved back to New York, where he tried getting involved with something similar in Brooklyn, while continuing with his Hollywood acting career.

Still a keen follower of the sport in the Fifties, Green thus discussed his forthcoming TV role with many of his friends who were still in the business, visiting local gyms and absorbing a few nuances of character from several of them that he felt would add to the authenticity of his own portrayal. He was confident, as a result, that this was going to be one of his best performances in years.

There was, indeed, a positive spirit in general about the production. Besides Green, the cast also included the Brixton-born Gary Raymond as Obie, the young boxer, and Kenneth Connor as Nat, his non-nonsense trainer. Armed with a good script, full of good comic lines and some moments of pathos as well, everyone involved was hopeful of making this one of the more memorable television plays of the year.

The only slight anxiety concerned the fact that it was going to go out live. 'Live television', recalled Warren Mitchell - who was one of those actors obliged to appear on it regularly in those pioneering days - 'produced in some people the absolute terrors. Some people went in a corner and vomited for hours on end. They couldn't eat for days!'

Mitchell, incidentally, had worked with Green the previous year, co-starring with him and Peter Welch in a comedy series for ATV called Three Tough Guys. Those shows had also gone out live, but, aside from a few minor mistakes, had been completed without any unexpected incidents, and Green had agreed with Mitchell that one of the few positive things about working 'without a safety net' was that they did not have to face the ordeal of watching themselves at a later date.

Most of the cast and crew for Poet's Corner had, by this time, developed their own individual coping mechanisms for managing 'live' anxieties, and were well-accustomed to the routine hazards associated with such a production. Actors were used to props malfunctioning, scenery wobbling or falling down and cues being missed, and had developed their own tried and trusted ways of responding to such sudden on-screen embarrassments. There was also a cut-out key - a device which cut the sound for a few seconds to allow actors, if they 'dried', to receive a quick hint as to the next line of the script, and, if that failed, there was always the last resort of someone in the studio simply shouting out the relevant sentence like a prompt would do in the theatre.

One way or another, therefore, the actors were reasonably well-prepared for the vicissitudes of live television. What none of them was prepared for, however, on that fateful summer evening in 1958, was for one of their colleagues to drop dead during the transmission.

This is what happened during the course of Poet's Corner.

It started normally enough. The title sequence commenced, the play was introduced, and away it went. As was the norm for live performances, it was a little rough around the edges - the odd line was fluffed and there was an occasional shake as the cameras were manoeuvred to a new position - but, in the eyes of the audience of the time, it was a decent enough production.

Two fairly long commercial breaks had been scheduled during the hour that the programme was due to run. The first one came and went without incident and the play resumed as planned. During the second one, alas, Harry Green collapsed in his dressing room from a massive heart attack.

What happened next is something about which we know mainly because it was witnessed by the comedy writer Brad Ashton, who, along with his partner Dick Vosburgh, happened to have just wandered into the studio after completing work on a recording of another ITV show. Expecting to stand in the shadows and watch the final third of the play being performed precisely as planned, they found themselves instead plunged into the eye of a storm.

It had taken a few moments for anyone to realise what had happened, but it was now painfully clear that a tragedy had taken place. Green had appeared in fine form up until that commercial break, and it was not unusual for him, in such live productions, to slip away during the adverts for a quick nip of something or other to refresh himself before returning for the next set of scenes (aside from a sip of whisky, he had a quirky little habit of munching on a hardboiled duck egg). This time, however, he had not returned.

Seeing the clock ticking on relentlessly towards the next part of the play, the studio manager had sent an assistant racing off to find the absent actor. The assistant raced straight back, white-faced and panting with distress, to deliver the news of what he had found in the dressing-room.

There was shouting, there was crying and there were gasps of distress. Some people were rooted to the spot in shock. Others were racing around in panic.

'What shall we do?' someone shrieked. They followed this with: 'What shall we do??'. People were now running in all directions at once. The whole studio was in chaos.

There was, by now, barely any time for them to react with any degree of logic. While several members of the backroom team tried to revive the unconscious Green, and a doctor was promptly summoned, it was left to the director, David Boisseau, to continue with the production.

Unsure of quite what was actually happening elsewhere in the studio, but forcing himself to block out all the noise, he sent the message down to the other actors that Green was indisposed and they would have to go on without him for the remainder of the play. When, spluttering with shock, they asked how exactly they were supposed to do that, given that Green's character was supposed to be present at several key points right through to the end, the director just managed to blurt out a very concise response - 'Just DO it!!!' - before the red light went back on.

Once the third and final act began, therefore, the remaining members of the cast, suddenly feeling very much exposed, were left to improvise their way to some kind of comprehensible conclusion. Perspiring wildly under the hot studio lights, with the cameras cruelly tracking their every move, they squirmed their way forwards, trying hard not to show the sheer panic that was now shaking them from within.

Kenneth Connor, as the most experienced of the surviving main actors, took it upon himself to insert the key plot details that Green should have been providing by pretending that the character was calling-in on the telephone. He might well have remembered seeing other actors resort to this ruse in the recent past, because, in this era of live TV, it was already a fairly common conceit: actors had fallen asleep backstage, or wandered off drunk, or found themselves locked in the lavatory, and the poor performer left on camera had felt there was no alternative but to pick up the telephone and start having an imaginary conversation with the missing member of the cast.

This was what Connor now did in front of the cameras. 'What's that, Mose?' he gasped, his tongue dragging its way slowly around his bone-dry mouth. 'You're stuck in traffic?...I know you should already be here!...Yes!...Well...You want me to do what, Mose?...'

The problem was that no one (and certainly not the sound effects operator) knew when Connor was next going to resort to this desperate measure, with the consequence that, whenever he did so, as the others stood by and looked bemused, his character was shown reacting to a telephone that was quite clearly not ringing. 'Hello?' he'd go, picking up the silent receiver expectantly. 'Oh, Mose, where are you now?...Oh, no, you're still stuck there, eh? How far?...We need to do what?...'

Eventually, this sixteen-minute segment, which must have felt to all in the studio like an eternity, finally staggered to its end, with the basic storyline somehow told and resolved, and then the credits duly rolled. The director gave out a deep groan of relief and promptly slumped over his desk, the shattered actors sank to their knees and the rest of the studio, not knowing whether to applaud or mourn, wandered around looking blank.

The crisis, however, was by no means over. The executives at Associated-Rediffusion were now in full-blown panic mode. As soon as the ambulance had taken Harry Green away to the nearby Edgware General Hospital, without there having been given any formal confirmation that he was already dead (no official announcement would be made, in fact, until shortly after midnight), the suits in the studio were engaged in feverish discussions as to how best to manage this highly distressing situation.

Fearing a horrified reaction if the news got out that they had gone on with the broadcast while one of the cast members was either dying or possibly already dead, it was decided that they would announce that Green had actually collapsed shortly after, rather than during, the production. They simply gambled that no journalist who had been watching had noticed the improvised nature of much of the final act.

That gamble, amazingly, paid off. The critics appeared to have regarded the final scenes as being part of the 'official' script, and they praised the play politely while paying tribute to the star who had since been declared deceased. 'It was to be expected of Harry Green', wrote one reviewer, 'that the very last performance of his life in Poet's Corner should have been packed with all the gusto, gaiety and exuberance of which this great comic actor is capable.' Another averred that the actor 'had given one of his characteristically ebullient performances', and that the play had served as a fitting farewell to 'a well-loved character'.

It seems highly unlikely that not a single journalist, with all of their countless contacts in television, had really failed to learn what had actually happened behind the scenes. It seems far more likely that they, or at least their editors, had decided that it would be best for them to draw a discreet veil over the specific details and limit themselves to noting that the death was only announced a couple of hours after the show had been screened.

The headlines that followed, therefore, all gave the impression that Harry Green had completed the play as planned and then passed out backstage. The messy reality was brushed very firmly under the carpet.

The obituaries followed promptly, full of warmth for a comic actor whom the British had come to think of as an adopted son ('We who only knew him through his appearances on TV', reflected one, 'were so impressed by his personality that we felt that we wanted to know him'). The following week, the next edition of Television Playhouse, entitled The Touch Of Fear, went out live again, and again involved another dead body, but this time, mercifully, it was a case of fiction rather than fact.

One might, indeed, be tempted to paraphrase Steve Coogan's sombre pool supervisor in The Day Today to underline how British television managed, far more often than not, to get through the era of live broadcasts without suffering any major calamity - 'In 1955, no one died. In 1956, no one died. In 1957, no one died...' - but that only makes an isolated instance of the contrary, such as this, all the more memorably alarming.

'Death is easy,' goes the old show business saying. 'Comedy is hard.' As the sad case of Harry Green showed, however, the challenge of the latter is always far more preferable to the finality to the former.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more