A Hackney diamond: The much-misunderstood Ray Martine

It is debatable which is worse: to end up a forgotten comedian, or a misremembered one. Ray Martine ended up as both: you've either no recollection of him, or else you've only a very partial memory of who he was, what he did and how well he did it.

Those who remember him at all tend to insist that he was an unfunny comedian who seemed to have no idea how to tell a joke, and who was therefore merely amusing in his incompetence. That is, at best, only even vaguely true of the latter phase of his show business career, and it hardly explains either how he got any work in the first place, or how he ended up having such an impact on the comic climate of his time.

If we take the time and trouble to recover the full story of Ray Martine, however, we will understand not just why he went wrong, but also how he went right. He was a far more complicated character than a comic who struggled with comedy, and his career, as a consequence, deserves to be better commemorated.

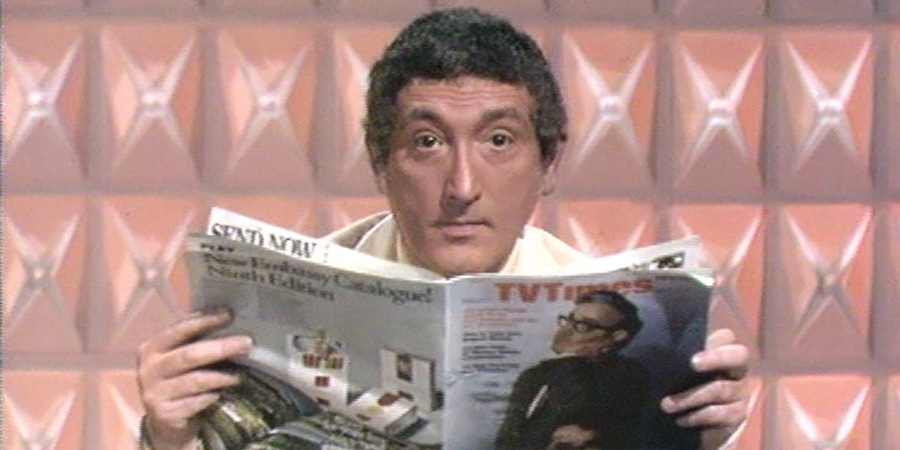

The main reason for the misleading myth of Ray Martine is the fact that the most accessible surviving record of him as a performer is his output in Jokers Wild. This ITV panel show, in which two teams of comics competed to come up with the best-received gags about certain set subjects, ran for eight series between 1969 and 1974. Barry Cryer was the host, Ted Ray and Arthur Askey were (for most of the time) the two captains and Martine, along with Les Dawson, was one of the regular team members.

View any of those episodes today (and, apart from being available on DVD, a few have been uploaded on to YouTube) and one will indeed find many of Martine's contributions to be bafflingly botched and bumbling, with most of the laughs appearing to come from his chronic incompetence as a comic (causing even his own teammate, Ted Ray, to at several points brand him on air as 'The Boston Strangler [because] he chokes all his own jokes'). There was, however, some background to this.

It was partly to do with his declining ambition (the show came long after his peak as a performer), partly to do with his discomfort at reading out other people's lines (much of the show's 'spontaneous' humour was secretly scripted, with several of his gags scribbled down on his desk), and partly to do with his role on the show (he was set up to be bullied by the others, who would interrupt him so often his stories frequently collapsed into incoherence).

This, however, is not at all what Ray Martine had always been like. Born Raymond Isaacs on 6th October 1928 to a Jewish family, he was a product of London's East End working-class, growing up in Commercial Road amongst an ethnically diverse, immigrant-rich community well-used to fighting against the odds.

His first job, upon leaving school, was as a messenger boy for Denham Film Studios, but was soon fired for pinching cigars and cigarettes from the bosses' desks and distributing them among the lowlier members of staff. He would show the same rebellious attitude in the many jobs that followed, leading to him either being fired for flouting the rules or else quitting out of boredom.

A spell of National Service followed, endured grudgingly in the Royal Artillery, and then he was back in and out of jobs, mainly working in the textiles industry and selling menswear, until, at last, he found something that he enjoyed being paid to do: 'singing, clowning and carrying on'.

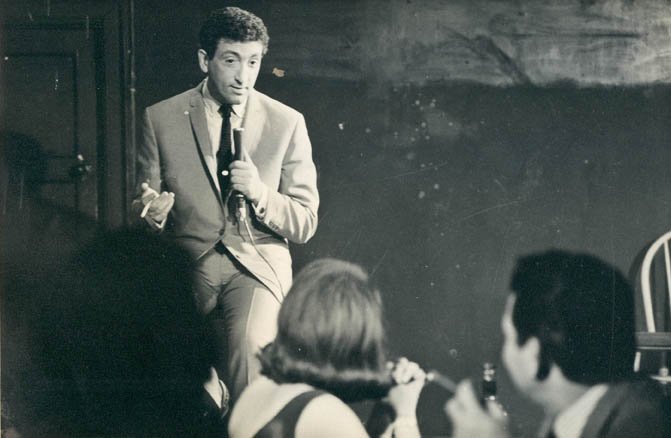

Right from the start of his performing career, there was something intriguingly prickly and passionate about the newly-named Ray Martine. When he strode up and stood by the microphone, his dark hair slicked back and his silk suit shining in the spotlight, he actively encouraged the hecklers. 'Why do you come here and interrupt me while I'm working?' he'd ask a man intent on intervening. 'After all, I don't go round to your workplace and flush all the toilets!' 'My dear,' he'd say to a woman who shouted something else, 'that dress you're wearing - it looks like something Marks made while Spencer wasn't watching!'

It took him a while to find his spiritual home. Having grown up enthralled by Hollywood and Broadway glamour, he thought that it would be America, but after spending a year or so there at the end of the 1950s, suffering one rejection after another by agents and promoters while struggling to survive by working as a bus boy for eleven dollars a week ('my feet were killing me'), he returned to England and, after a few open mic night experiences, realised that London's rough and raucous pubs were the places that best suited his combative style of stand-up comedy.

Seemingly fearless in material and manner, some started likening him to an English Lenny Bruce in the way that he attacked controversial subjects without the slightest hint of a compromise. If a swear word was thrown at him he'd throw a far worse one straight back. If someone tried to offend him with a racial or sexual insult, he'd humiliate them by deconstructing their dogma. If someone challenged him to a fight he'd claim to be ready to accept it.

With his good looks and stylish clothes he looked ready for a life of glamour but remained committed to the culture and community of the working class. 'These are my people,' he would snarl when asked why he continued playing the pubs and clubs. 'The rich can get lost!'

Gay when gay activity was illegal, and Jewish when antisemitism was depressingly widespread, Martine was simply incapable of denying his authentic identity. He was not campaigning, he was simply being: being himself, and being waspishly funny.

One of the first influential people to champion him was Terry-Thomas, who came back to Britain from a spell in Hollywood at the start of the 1960s, wandered into an East End pub, and was so impressed by Martine's performance and presence (coming from a similarly modest background, and having a similarly unapologetic attitude, he sensed a kindred spirit) that he started urging all his friends in the press to go out and see him in action. 'I've just been with one of the most witty, sophisticated, outrageous, devastatingly funny comedians in show business,' he drawled down the line to one journalist acquaintance. 'You simply must go and see him at once. All you've got to do is to tootle along to the Deuragon Arms in Rosina Street, prop up the bar until 9pm when a chap called Ray Martine arrives and then hold your sides!'

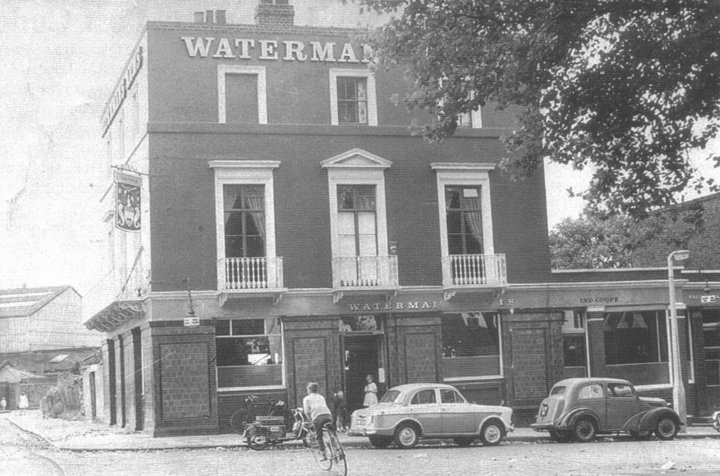

Soon after, the writer Daniel Farson became another significant supporter. Marvelling at how ruthlessly Martine dealt with unruly crowds, he booked him to appear at his own newly-acquired East End pub, the Watermans' Arms on the Isle of Dogs. Martine performed there alongside the even more camp and cutting drag act Mrs Shufflewick (portrayed by Rex Jameson), and the tough and talented actor and singer Queenie Watts.

Increasingly in demand, he was also soon installed as the resident compère and comic of the more mainstream Whisky A' Go Go nightclub at 33 Wardour Street in Soho. Already widely celebrated as a hero in Hackney, he was now, as one critic put it, fast becoming 'something of a legend' in London as a whole.

He knew that all of these venues - especially the first two - had a strong (but by no means exclusive) association with the local gay community. He knew that they also had a strong local appeal for the Jewish community. Both of those things mattered to him, but neither mattered that much. He mainly wanted just to make people laugh - but only on his terms. Never had a British comic seemed less inclined to even the slightest degree of ingratiation, no matter how neat the fit might have been.

One could only look on in awe at his apparently complete lack of interest in courting popularity. Now sporting a tightly curled hairstyle that suggested an angry Caligula heading off for one last heart-to-heart with his horse, he was more intimidatingly temperamental than ever, with a smile that could, within a second, switch easily into a sneer.

'Political, racial, sexual, homosexual, and other stand-by fodder for funny men was delivered with subtle observation that would have most chi-chi club members baffled,' wrote one impressed observer. 'The young patrons dug every sly innuendo and yelled for more.'

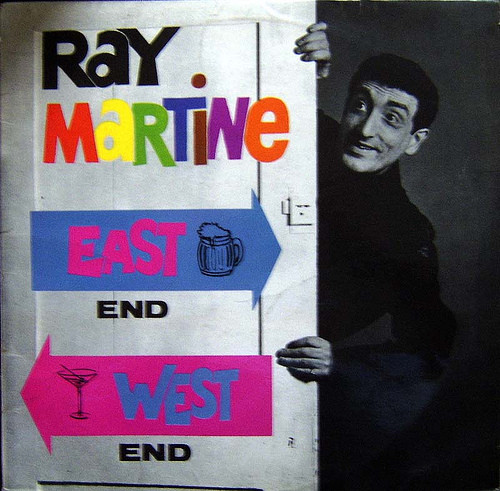

A reasonably vivid (though somewhat censored) record of what his performance tended to resemble during these early days (he described it himself as 'a bit of clowning and carrying on') was captured on his album, East End, West End (1963). Contending with a noisy and excitable audience pressed close up and personal, he delivers his opening gags in a slightly rasping, lightly lisping manner, more in the style of an auctioneer than a comedian, holding each one up indifferently for inspection before slamming down the gavel and moving on to the next item. 'I'm just putting them up for sale,' he seems to be suggesting; 'it's up to you if you want to buy them.' Then, accompanied by a pianist, he indulges in some rambling tall stories, breaking off every now and then to put the many hecklers in their place ('I think I deserve a big hand. And so do you - right across the face!').

The fact that the record was ever released (even in edited form) was itself a testimony to Martine's unusually uncompromising attitude. Whereas most other comedians' albums of that era were invariably slickly selected highlights made from multiple performances, with all of the flaws and fluffs taken out, his own chosen offering happily embraced the sheer messiness of his usual appearances, suggesting there was actually a craft in the carelessness. It was chutzpah at its highest level, and it was typical of Ray Martine.

It would be wrong to romanticise his act. In terms of material, it was always, to put it politely, hit and miss, and, far more damagingly, the man himself had a nasty habit (which was sadly all-too common in, amongst many places, the gay pubs and clubs of the time) of making misogynistic remarks when the hecklers happened to be women. In terms of the stand-up comedy of the era, however, it must be acknowledged that no one else in Britain seemed quite as authentic or as edgy, or even as dangerous.

It was why the broadcasters of the time were simultaneously excited and unnerved by him. He was the modern, distinctive and excitingly unpredictable comic of their dreams - and their nightmares. Their basic calculation had to be: was the likely rise in the ratings going to outweigh the probable increase in the complaints?

His first step towards reassuring them was when, early in 1963, he accepted an offer from Peter Cook to appear at his new and fashionable centre for satire, the Establishment Club. Challenged with the task of retaining the essence of his aggressively irreverent style while engaging with a different, somewhat broader and supposedly more 'sophisticated' audience ('spirit rather than beer drinkers' was how he saw it), he succeeded without any signs of strain.

It also helped, hugely, that Terry-Thomas continued to be such a forcefully vocal fan, recommending him to whomever he encountered during his regular visits back to Britain. Describing him to his media friends as 'the funniest man in the world', he made a point of urging television producers to snap him up for the small screen.

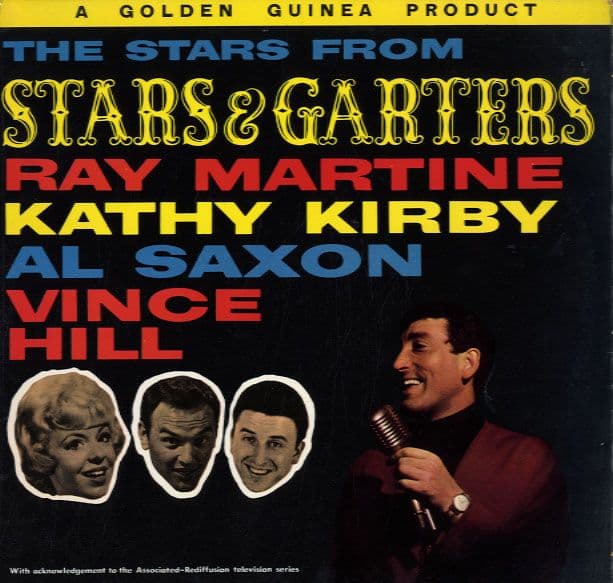

The first to act on T-T's advice would be John Hamilton, a producer at the commercial TV company Associated-Rediffusion. In April 1963, he picked Martine to be the compère of a new variety series called Stars And Garters.

Shot in a studio at Wembley Park but set at the fictional 'Stars and Garters' public house, it was envisaged as a kind of vicariously boozy night out for those who were watching at home, with regular singers Vince Hill, Sandra Gale and Kathy Kirby supplemented by a range of special guests selected each week from the pub and working men's club circuit. Martine was considered the most suitably 'authentic' host for such an unapologetically rough and ready sort of show, although it was decided (by Elkan Allen, the Head of Variety at the channel) that, as the programme was set to go out 'live' and his usual material was deemed far too 'blue' for a TV audience, his gags would have to be specially scripted by a team composed of Barry Cryer, Dick Vosburgh and Marty Feldman.

Martine, predictably, was resistant to this idea when it was first suggested, but once he saw a sample of their writing, and realised not only how good the lines were but also how well they suited his style, he was happy enough to comply. He wanted to try television, and he wanted the best possible material to help him make a success of it.

Making its debut at 10:15pm on Friday 31st May, Stars And Garters proved an instant hit. Far ahead of its time in terms of its freewheeling format (anticipating the likes of Chris Evans's TGI Friday of the 1990s), while still retaining, in a fast-moving decade where all that was solid seemed to be melting into air, a reassuringly nostalgic affection for the mood of the music hall, the production walked the tightrope across the prime-time/late-night divide with only the occasional wobble, and Martine, with his mixture of feel-good crooned cabaret tunes and (even after being tamed slightly by his writers) daringly up-to-date and edgy style of humour (he was, one might say, the non-drag version of Lily Savage long before Paul O'Grady had ever thought of his more acerbic alter-ego), seemed the epitome of the show's Janus-faced appeal.

As an ostensibly mainstream entertainer, Ray Martine really intrigued people. To those who were not already familiar with his record of combat in the Hobbesian hurly-burly of the toughest London pubs and clubs, he seemed a sort of Mephistophelian version of Bruce Forsyth, embodying a mood of much more menace as well as mischief, able to sing and joke and mess about with the audience but with a cooler air and a crueller attitude.

Dubbed by one television critic as 'the sickest comedian we have in this country' (and that was meant mainly as a compliment), he was asked how he had coped with the sudden transition from club comic to TV star. 'I was nervous,' he admitted, 'but then I remembered my philosophy: "I don't give a damn". People are the same whatever their class, and they all want and need a good laugh. I hope to give it to them and to get by because I revel in being an exhibitionist.'

Because of his abrasive attitude and near-the-knuckle comic asides, he would remain an unusually divisive figure for critics and viewers alike. One journalist, for example, condemned him for performing 'some of the nastiest material I have ever heard on TV,' complaining haughtily that 'if that sleazy, down-at-heel humour wins over yoicks in saloon bars then all I can say is - keep it there! We don't want it on TV'. Others, however, were delighted by the defiance in his demeanour, with one celebrating his 'air of spontaneity,' along with the fact that he 'doesn't look so frightfully pleased with himself as most compères do,' while Dennis Potter (in those days reviewing TV shows whilst pursuing his own ambitions as a budding playwright) defended him for being drawn towards 'smut' ('Who cares?' Potter protested, recognising a similarly subversive soul. 'Children should be in bed at this hour').

What Ray Martine was culturally, above all else, during this time, was a talking point. Whether one liked him or loathed him, he got people discussing and debating him, show after show, week after week. His TV employers, as a result, were delighted with the impact he was making, and promptly extended his original six-week contract to seventeen weeks and also dramatically increased his pay.

A second series started in December 1963 (this time recorded rather than transmitted live, partly so as to enable some discreet censoring of its star's edgiest ad-libs). By now, the publicity machine was clanking so noisily around Ray Martine - there was talk of tours and albums and visits to Broadway, Las Vegas and Hollywood - that even he, for all his scorn for the superficiality of show business, allowed himself, in a rare moment of weakness, to be drawn into the dark arts of the image game, and was persuaded that a 'lavender marriage' would protect his position as a celebrity. He thus let it be known that he had become engaged, in the middle of that month, to a twenty-three-year-old fashion designer named Jeanne Mandrey, and a story was duly planted in the press.

It soon became apparent, however, that not only did too few people seem to believe it - although Martine didn't (and legally couldn't) discuss his sexuality publicly, arguably no contemporary British gay celebrity put less effort into hiding his true identity - but also, refreshingly, not enough people seemed to care. The marriage plans, as a consequence, were quietly dropped, and Martine, feeling thoroughly ashamed to have even contemplated such a cynical move, vowed never again to be anything other than honest about his own life.

The second series went ahead and did better than ever in the ratings, as well as being singled out by one tabloid newspaper as the 'TV series of the year,' and Martine then followed its success by touring the country to packed houses with a stage version of the show. A third series began in December of 1964, and continued to attract big audiences and plenty of positive coverage by the press.

Ray Martine was, by now, a familiar figure in the cultural landscape of the country, pictured socialising with everyone from Noel Coward to The Beatles, playing the biggest clubs for the biggest fees and being sounded out about countless lucrative cabaret deals and various business opportunities. It was at this stage, just when he felt that he could do wrong, that things started to go wrong.

Encouraged by his sense of stardom, he started assuming more control over his television routines, using more of his own material, and less of his writers', and ad-libbing more freely and daringly during his shows. His producers, fearing all kinds of potential controversies (Mary Whitehouse's 'Clean-Up TV' campaign was by now clanking noisily into action), started cutting a greater number of his lines from the recordings, playing havoc with the timing of the shows and causing more and more rows behind the scenes.

Martine, however, carried on regardless, making increasingly cutting remarks about the increasingly underwhelming acts that were being booked for the show. 'She's the only girl who can do community singing by herself,' he said with a scowl about a woman who played the drums while barking out a song; 'It's all right, you can come out now, they've gone,' he said to the cameras about another performer after they had staggered off the screen in silence; 'Nope, me neither,' he muttered conspiratorially, with a sigh and a shrug of the shoulders, as one more mediocre act came and went.

It was not just some of the viewers who were now complaining about Ray Martine. It was some of the participants, too.

His producers, as a consequence, were starting to pine for a more pliable host. Martine, for all his sparkiness on stage (and all the coverage he inspired in the papers) was simply becoming, for some, too much trouble to tolerate. The decision was therefore reached, after much internal debate, to drop him from the show.

His last appearance on Stars And Garters would be in a summer special, which went out on the evening of 9th August 1965. He knew it was going to be his final performance - the news had been delivered to him some time before, and this edition was intended as a suitably, if hypocritically, respectful valedictory outing for the man who had made the vehicle a hit.

He told reporters, in the days leading up to the broadcast, that, while the decision had not been his own, he had no regrets about ending the association. 'I haven't been asked to return,' he revealed. 'But I don't mind.'

'I was getting in a rut,' he went on to say. 'I compèred sixty of these shows, and its's very difficult to keep being funny in thirty-second bursts between songs.'

Stars And Garters would return as The New Stars And Garters, with Jill Browne and Willie Rushton as the co-presenters ('blue jokes,' it was promised in the papers, 'will be out'). Martine's next venture, meanwhile, would see him make his debut as an actor in a stage play, called Love On Ice, about an ageing ice-cream salesman.

The New Stars And Garters flopped with its new format. Martine fared no better with Love On Ice.

Suddenly, he found himself back on the outside looking in. Suddenly, he found he was slipping from a star to a former star.

Slowly but surely, as his on-screen absence was noted, other comics, like sharks scenting blood, started swimming in for the kill. 'Ray Martine would be the most popular man on TV,' Bob Monkhouse (cosily in pot/kettle mode) observed 'if he was as well-known as his jokes.' There were many similar snipes like that, which Martine accepted publicly with good grace (he admitted, if fortunes were reversed, he'd probably do the same himself), although, privately, they still stung.

His old producer, John Hamilton, remained loyal enough to book him for a children's teatime show he was making called The Five O'Clock Club. It was a kind gesture, and warmly received, but it was hardly suited to Martine, who had to sustain a simpering expression whilst singing Put On A Happy Face to a bunch of somewhat nervous-looking London schoolkids.

He did considerably better at the start of 1966 when he was given a minor role in an episode of The Avengers (The Girl From Auntie) playing a taxi driver. It was a non-speaking part (which, given his gift of the gab, made it clever casting), but, as he had to face the camera while chaos happened behind him, it gave him an excellent opportunity, via his range of facial expressions, to show that he really could act.

It did not lead to further offers, however, and Martine would spend most of the second half of the decade back on the cabaret circuit. He was usually billed as 'Television Star Mr Ray Martine,' but, as the years went by, that soubriquet sounded increasingly quaint. With his abrasive style now frowned upon by many producers (some of whom, privately, were also not keen on his openly camp manner), he feared he had been frozen out as far as mainstream TV was concerned.

Rather than attempt to reinvent himself, however, his reaction was to concentrate on the clubs, doing what he did best, but more openly, honestly and outrageously than ever. It brought him a considerable amount of success, with some record-breaking appearances at some of the best venues in the country, as well as, on occasion, quite a bit of controversy (his 1968 summer season at the Central Pier in Blackpool, for example, saw him sacked following complaints about his 'filthy' material - he was subsequently reinstated once he agreed, reluctantly, to 'tone it down a bit'). Revelling in his reputation, as he put it, as 'the black sheep of show business,' he seemed relieved to be free of the compromises that came with working on TV.

In 1969, however, the medium had another message. The scriptwriter Sid Colin, one of his old friends and now Yorkshire Television's recently-appointed Head of Light Entertainment, was assembling the cast for a pilot edition of a proposed competitive gag-telling show called Jokers Wild, and persuaded Martine to join the team. Filmed in Leeds on 15th April, it passed all the panels, a full series was commissioned, and Ray Martine found himself back on television.

He was not, in truth, that excited to be back. Having grown used again to the greater liberty he was afforded in the clubs, he was in no mood to submit to the old constraints. He was happy enough to regain the nationwide exposure, along with the extra income, but this time around he was only going to treat it as a part-time activity that supplemented his 'proper' stand-up appearances.

When it came to defining his role on the show, it was the realisation that he would never get away with his usual club material, along with his disinclination to work that hard at coming up with something more 'family friendly,' that led him to settle for being a kind of unofficial comic foil for all of his fellow comics. Making the minimum amount of effort, he would thus stumble his way through the corniest material he either already knew or was handed by the scriptwriters, allow the others (especially Les Dawson, who rapidly became his main tormentor) to heckle him from start to finish, and then he would take his bow, pick up his latest cheque and head off back to cabaret.

It was a novelty at first to see Martine, having made his name as the arch comic aggressor, accept being the butt of other's barbs, but soon it became accepted as the norm (to the point where 'Interruption by Les Dawson' seemed to be the second line of most of his jokes, and the latter stages of the most rambling of them were sometimes accompanied by snoring noises). 'That was the end, wasn't it?' inquired the chairman Barry Cryer after the latest story had stopped to the sound of silence. 'Reassure me that was the end?'

Most of Martine's own jokes were indeed terrible, but then so were most of the ones told by the others, and he was actually, at least in the early days of the show, the participant who elicited the most positive critical reactions ('The one man to stand out in this,' wrote a reviewer during the first series, 'is undoubtedly Ray Martine,' while another dubbed him the programme's 'erratic maestro'), with the mock-bullying lending him at least the appearance of a degree of vulnerability that viewers hadn't previously seen. As the run continued, however, his enthusiasm clearly declined, as did his industry, and Martine became Marmite as far as the show was concerned, with his carelessness now irritating almost as many as it still amused.

It did not bother Martine, whose live act was now so popular on the northern club circuit that he had bought a bungalow in Blackpool and was going from strength to strength on the local stages. He was more relieved than disappointed when Jokers Wild finally came to an end in 1974, knowing how long on the show he had simply been going through the motions. 'I was disenchanted,' he would say. 'Why be disenchanted when you can be happy?'

The only irritation he now had was with the hypocrisy of a culture that since the Sixties had been applauding itself as 'permissive' but, to his eyes and ears, remained anything but. Still suffering frequently from homophobic and racist insults and intolerance, while often being chastised for attacking such attitudes in his act, he preferred not to associate himself with the show business establishment.

Describing himself as the 'only funny man I know who is too blue for colour radio,' he railed against the attitudes of the time. 'We are crazy as a society,' he said, 'we allow our children to watch all sorts of violence on television, yet draw back at saying "knickers". I find the lack of censorship of violence much more worrying. That is obscene to me, not the things I say on stage.'

He was based in the Lancashire village of Marton by now, picking and choosing his theatre engagements more carefully while devoting a larger portion of time to his longstanding passion for buying and selling antiques, adding regularly to a collection that included many fine Victorian, Edwardian and art deco items along with a special selection of miniature furniture ('I have seven miniature sets of toilets,' he would say with a laugh. 'Okay, so I'm mad!').

When the 1980s arrived he moved on to Cowgate in the north-west of Newcastle upon Tyne, stopped performing and started trading professionally as an antiques dealer. Although he would be tempted back to the stage for the odd project - which ranged from role as Trinculo in a truly bizarre 1988 production of The Tempest at the Salford Playhouse, with the likes of the squeaky-voiced ex-pop star Freddie Garrity and Jack (Love Thy Neighbour) Smethurst among the other members of the cast, to a one-line cameo in 1992 for the Ant and Dec teatime drama series Byker Grove - he had no desire to return full-time.

His final few years would be lonely and sad. Having seen most of his savings slip away ('I got through a fortune,' he said, 'and a lot of people - spongers who later disappeared - helped me spend it'), and following a car accident that left him too nervous to drive, he became something of a recluse, drinking heavily and only sharing his still-wicked wit via the occasional phone call with old friends.

He died, from liver disease, in a Newcastle nursing home on 19th June 2002. He was seventy-three.

'When the history of modern British humour comes to be written', wrote the critic Peter Hepple back in 1970, 'I trust that Ray will receive his due share of praise, because he was something of a pioneer [...] and a genuine original in the comedy field - honest, self-mocking and treating an audience in a way that many other comedians wish they had the nerve to get away with.'

It was a sound enough contention, and certainly a far fairer one than the more common claims made about him these days. Few, if any, did more at the time than Ray Martine to make the world of British comedy at least a slightly more tolerant and curious place. He was the outsider who broke inside, withstood all the blows of bigotry, and left a space behind through which so many others could, and did, follow.

It shouldn't be Ray Martine that we forget; it should be the myth that has been manufactured around him. Contrary to the clichés in the retrospective commentaries, he always knew what he was doing, and how, and why, and for whom he was doing it. He thus deserves to be far better remembered, and more properly respected, for the admirable defiance of his spirit and the distinctiveness of his style.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreJokers Wild - The Complete First Series

"I was working in a pub when this hippy came in, jingling his bells. I said 'are you one of the flower children?'. He said 'no - I've got leprosy.'"

Running for 8 highly successful series, Jokers Wild was a lively, rapidly paced panel game in which two teams of top comics competed for laughs from the studio audience. While team members delved into their repertoires for winning jokes based on topics drawn randomly from an oversized pack of cards, bonus points could be scored by opposing team members if they interrupted mid-gag to complete a punchline.

Hosted by comedy legend Barry Cryer, the show's line-up often read like a who's-who of British comedy talent - John Cleese, Bob Monkhouse, Diana Dors, Eric Sykes and Sid James being just a few of the famous players over the course of its five-year run. This first series, featuring Les Dawson, Ted Ray, Charlie Chester, Jimmy Edwards, Alfred Marks and Roy Hudd among others, was originally screened in 1969.

This 3-disc box set not only includes the entire first series, but also an unbroadcast pilot episode, recorded in April 1969.

First released: Monday 31st January 2011

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 3

- Catalogue: 7953415

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Jokers Wild - The Complete Second Series

Hosted by comedy legend Barry Cryer, Jokers Wild is a who's-who of British comedy talent from the 1970s; this second series features Ted Ray, Arthur Askey, Les Dawson, Ray Martine, Clive Dunn, Lance Percival, Jack Douglas, Graham Stark, Eric Sykes, Kenneth Connor, Alfred Marks, Professor Stanley Unwin and Ted Rogers, among others.

This series was originally broadcast in 1970; Jokers Wild's most successful year, when Series 2, 3 and 4 were shown back to back on ITV in an exceptionally popular eight-month run!

First released: Monday 14th November 2011

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 2

- Catalogue: 7953606

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.