Freddie Frinton's Dinner For One

When is a British comedy legend not a British comedy legend? The answer, as far as the case of Freddie Frinton is concerned, is when you are British and a comic legend in most places except Britain.

Freddie Frinton is quite an obscure figure these days in the country of his birth. In the 1960s, however, he was one of Britain's most popular comic performers, co-starring with Thora Hird in a sitcom, Meet The Wife, that was such a fixture on television in those days that it became immortalised by John Lennon in one of the tracks - Good Morning Good Morning - on Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band ('It's time for tea and Meet The Wife').

He died in 1968, but ever since then, at this time of year, his eighteen-minute comic sketch, Dinner for One, is watched in countless countries all over the world - but rarely in the UK. It makes him seem a bit like Tony Hancock in The Radio Ham: 'I've got friends all over the world - all over the world! None in this country, but all over the world!'

Not only has the extraordinary cultural impact of Dinner for One been largely ignored in this country, but also, on those rare occasions when it has been recognised, its history has usually been misrepresented. What follows, therefore, will seek to put the record straight about one of Britain's unjustly forgotten comedians and the real story of his legendary sketch.

Frinton himself was a man who acquired some interesting contradictions during the course of his career. He came from Lincolnshire but usually played, and sounded like, a Lancastrian; he was a teetotaller who specialised in portraying, very convincingly, comedy drunks; and he was a fiercely patriotic Englishman who ended up being appreciated most avidly by foreigners.

As far as the basic details about the life and career of Freddie Frinton are concerned, they fit the familiar pattern for northern comedians of his era. It is a tale of tough beginnings and dream-driven diversions.

Born in Grimsby, Lincolnshire, in 1909, the illegitimate son of a dressmaker, he was originally named Frederick Bittiner Coo, but, once he was taken in by foster parents, was known as Freddie Hargate. With his cheerful personality and his cheeky gap-toothed grin, he had a natural gift for entertaining people, but drifted half-heartedly through a succession of menial labouring jobs until his passion for performing became too powerful to keep ignoring. After being fired from the local fish-packing warehouse, Forbes & Fish, for making his co-workers laugh too much, he took a fairly typical route into show business for a working class youth of that time and place: a year or two playing the pubs and clubs, and then a succession of provincial tours with concert parties and revues.

Adopting the stage name first of 'Freddie Fraser', and then (in the hope of improving his national appeal) the more southern-sounding Freddie Frinton, he established himself rapidly as a precociously versatile character actor and one of the funniest and most distinctive pantomime dames of the period. By the late 1930s, he was already being referred to as a star, and (after spending much of the war as a member of the military touring troupe Stars In Battledress, working alongside the likes of Tony Hancock, Terry-Thomas, Kenneth Connor and Jon Pertwee), he soon had his first West End hit as the successor to Sid Field in the revue called Strike A New Note.

For a while in the 1950s, he was one of the busiest and most popular comedians in the country. There were a succession of high profile stage shows, along with annual pantomimes and summer seasons, as well as a number of movies (including Penny Points To Paradise, 1951, and Stars In Your Eyes, 1956), and he even had his own comic strip in Film Fun.

He still played a wide variety of characters, from shady Cockney spivs to brusque northern businessmen, but the comic portrayal for which he now won most critical praise was as a doddery drunk in a rakish top hat and a semi-detached shirt collar, introducing himself on stage with the catchphrase, 'Good evening, Ossifer,' while waving absent-mindedly his trademark broken cigarette.

Towards the end of the decade, however, the variety circuit was dying and Frinton found work so hard to come by that he put his house up for sale and planned to give up show business, move to a village in Sussex, and run a grocery shop instead. His career was only saved because his fellow comic Arthur Haynes, who had been given his own television show, asked Frinton to be a regular member of the cast playing his already very popular drunk character.

The national exposure turned his fortunes around, and he was soon back starring in major productions on stage. Things got even better when, after his on-stage chemistry with Thora Hird was noted (they were co-starring in The Best Laid Schemes at Torquay during the summer of 1963), he was paired with her on TV in their own BBC television sitcom, Meet The Wife.

A kind of template for the much later Keeping Up Appearances, the comedy of Meet The Wife came out of the tensions between an upwardly mobile wife (Hird) and a defiantly unambitious husband (Frinton). Written by Ronald Wolfe and Ronald Chesney - later of On The Buses fame - it proved a major mainstream success, running for five series, and thirty-eight episodes, from 1963 to 1966, attracting at its peak audiences of about 15m every week.

It was Hird, rather than Frinton, who decided to quit the show while it was still high in the ratings, but the co-stars parted amicably, and Frinton returned to working mainly on the stage. There would follow the usual seasonal cycle of pantomimes and summer seasons, but he was still eager to be known for other projects.

There were occasional guest spots on various TV shows, a number of plays and revues, and in the summer of 1968 he made a pilot for the BBC's Comedy Playhouse of what he hoped would become a new sitcom for him: The Family Of Fred. The sudden decline of his health, however, prevented it from progressing (it would later be recycled for Jimmy Jewel as Thicker Than Water).

He continued to perform right up to the end. After suffering a heart attack while working in Bournemouth, where he was appearing in a comedy at the Pier Theatre, he died at the Central Middlesex Hospital, Park Royal, on 16th October 1968, aged just fifty-nine.

'Freddie, the TV drunk, is dead,' said one newspaper, with others choosing similar headlines, and, for the most part, it was indeed his drunk act, along with his work on Meet The Wife, that were cited as the defining highlights of his career. In the immediate years after his death, however, that sitcom, along with all of his other shows, would fade away from many people's memory, and, in Britain, he gradually fell into obscurity. Elsewhere, however, his posthumous fame started to flourish as the cult of Dinner for One began.

Dinner for One was a brief slapstick sketch that Frinton had performed, on and off, throughout much of his career. It was about a rich old lady, Miss Sophie (played in the early days by either Sonnie Willis, Bridie Devon or Joan Cibber, but later and more famously by May Warden) celebrating her ninetieth birthday, at the end of another year, at a dinner overseen by her similarly elderly butler, James (Frinton), with additional places set for four beloved guests long since dead:

MISS SOPHIE: All five places are laid out?

JAMES: All laid out as usual.

MISS SOPHIE: Sir Toby?

JAMES: Sir Toby, yes, he's sitting here this year, Miss Sophie.

MISS SOPHIE: Admiral von Schneider?

JAMES: Admiral von Schneider is sitting here, Miss Sophie.

MISS SOPHIE: Mr Pommeroy?

JAMES: Mr Pommeroy I put round here for you.

MISS SOPHIE: And my very dear friend, Mr Winterbottom?

JAMES: On your right, as you requested, Miss Sophie.

MISS SOPHIE: Thank you, James. You may now serve the soup.

Frinton, as James, was obliged, for every course, not only to serve all five places their food (the menu consists of mulligatawny soup with sherry, North Sea haddock and white wine, chicken and champagne, and fruit and port), but also to take the part of each absent friend in toasting the health of his mistress, thus becoming increasingly inebriated with each new serving of wine, and repeatedly tripping over the tiger skin splayed out over the floor as he totters off to get the next bottle:

MISS SOPHIE: Sir Toby!

JAMES: Cheerio, Miss Sophie, me gal.

MISS SOPHIE: Admiral von Schneider!

JAMES: Oh, must I say it this year, Miss Sophie?

MISS SOPHIE: Just to please me, James!

JAMES: Just to please you, very good, yes. Skål!! [He clicks his heels together painfully]

MISS SOPHIE: Mr Pommeroy!

JAMES: Happy New Year, Sophie gal!

MISS SOPHIE: And dear Mr Winterbottom!

JAMES: Well, here we are again, old luv, here's to me and thee, lass!

Each new course would see James enquire, with more and more of a slur, 'The sh-sh-shame prosheedure as last year, Miss Sophie?', to which she would always reply brightly, 'Same procedure as EVERY year, James!'

The ritual would finally end with James, swaying uneasily from side to side, accompanying Miss Sophie as she heads up the stairs to bed:

JAMES: Oh, by the way: the same procedure as last year, Miss Sophie?

MISS SOPHIE: The same procedure as EVERY year, James!

JAMES: Well...I'll do my very best!

The extraordinary success of this sketch after Freddie Frinton's death (it is now, according to the Guinness Book Of Records, the most repeated annual television show of all time), has led to a growing number of commentators noting its international impact. The problem is that most of these commentators have produced such inaccurate and muddled accounts that the truth has been marred by a myth.

Take, for example, these commonly-claimed misconceptions: Freddie Frinton acquired the sole legal rights to Dinner for One 'shortly after the war' (wrong); he allowed it to be filmed 'only once' (wrong); it was first discovered by foreign broadcasters when they were 'in the audience for a Blackpool matinée in 1963' (wrong); it was 'first shown on German TV in a programme called Guten Abend, Peter Frankenfeld' (wrong); and it 'was never shown during his lifetime on UK TV' (wrong).

We can deal with these inaccuracies one by one. First: Frinton did not acquire the formal rights to Dinner for One shortly after the Second World War. The sketch, which had been written by Lauri Wylie and originally performed by Bobby Howes and Binnie Hale in a West End revue, dated from the 1920s, and had been revived by a broad range of comic actors since then, including, of course, Frinton himself.

After seeing it performed by a touring company during the early 1940s, Frinton added new material by his friend, the Liverpudlian comic Harry Rowson, together with some original physical business of his own. He then presented his 'new' version for the first time at Blackpool in 1945, and repeated it there and elsewhere in many of the following seasons - but he only had an informal agreement regarding the rights.

It would in fact not be until 1967 that he finally got around to buying the exclusive rights for Dinner for One (as it was announced on 18th May 1967 in The Stage: 'All rights in the sketch Dinner for One are now exclusively vested in Mr Freddie Frinton and accordingly all enquiries concerning its future use in any form whatsoever must be addressed to Mr Frinton's agents...').

The informal arrangement was all that he needed when he was building up his career (he was simply so brilliant in it that he had made it his own in the eyes of the public and critics alike, and his long-term commitment to the piece had enabled him to negotiate a very modest royalty payment). By the mid-fifties, the sketch, thanks to him, was already being referred to as a 'comedy classic' and was also proving eminently adaptable, fitting into a solo evening's performance as well as any other production he happened to be offered. 'As a general rule I am all for fresh material and frequent change,' wrote one theatre critic in 1955, 'but just the same I would never miss an opportunity of seeing this sketch again and again.'

It eventually earned Frinton sufficient funds for him to buy a number of properties, including a confectionary and tobacconist's shop, but, while delighted with the financial stability it generated, he continued touring the act throughout each and every year. Once the 1960s began, he was shoehorning Dinner for One into just about everything he did on the stage - revues, pantomimes, plays, variety shows and club or cabaret appearances (not only in the UK but also in France, Germany, Italy and Las Vegas). He usually found a way to slip it somewhere or other in the running order, and, as it remained such a guaranteed audience-pleaser, no one else involved in the various productions had any cause to object to its inclusion.

This brings us to the second misconception. There is another common claim these days that the routine was never seen on British TV during Freddie Frinton's lifetime. This, once again, is untrue. In fact, it was seen once - but only by accident.

It is true that, throughout his career, Frinton resisted filming Dinner for One for British television - because he feared that such nationwide exposure would diminish its ongoing appeal as the central element of his theatrical productions. He had no such compunction, however, about filming it for foreign television, because he reasoned that such screenings would have no bearing on the continuing British appetite for his stage version.

This is where he would end up making a major mistake.

In 1960, the producers Gianni Proia and Antonio Altoviti flew over to England from Italy in order to see Frinton perform the piece during a summer season (called The Big Show) at the Opera House in Blackpool. They loved it, signed him up (after some haggling over his fee), filmed the act, and featured it in the international variety film, Il Mondo di Notte (The World by Night), which was released in April the following year. This, therefore, was the routine's debut in recorded form.

In December 1961, Frinton (as always, by this stage, in the company of May Warden) again agreed to film the sketch, this time in Hamburg for German television (but, as he had been a troop supervisor in World War II, and still harboured strong ill-feelings towards the country, he insisted on the performance going out in English, without any dubbed or subtitled translation). Made by Norddeutscher Rundfunk (Northern German Broadcasting, or NDR for short) and entitled Bitte, lassen Sie sich unterhalten (Please, Let Yourselves Be Entertained), it was a Christmas variety special, featuring numerous international acts, and Dinner for One was hailed as one of the highlights.

The impact was sufficiently impressive for Frinton to be brought back over to Europe again, two years later, to reprise the routine, shortly after finishing his stint as King Blotto in the Frog Prince pantomime at Bradford. He had agreed to film the sketch in Zurich, on 20th April, for Schweizer Fernsehen (Swiss TV). Featured as an insert in an international variety show called Nightclub (other guests included Bertice Reading, Ester Ofarim and Maria Perego and Her Marionettes), the sketch was staged in a more minimalist style than usual, but still proved extremely popular with the viewers.

In spite of his lingering antipathy towards Germany as a country, he also consented to travel there again while he was on the continent to make yet another recording of Dinner for One. Some sources now claim that he appeared on German TV on 8th March 1963 in a show called Guten Abend, Peter Frankenfeld. This is incorrect: that particular series (which in any case was mainly a game show) had ended two years earlier, and had never featured Frinton.

There does not in fact appear to be any record of Frinton appearing in any show formally hosted by Frankenfeld during this period. What we do know is that Frankenfeld (a chronically ebullient, brashly check-jacketed figure who was a near-ubiquitous comic, quiz master and game show host - a sort of German equivalent of Britain's Bruce Forsyth) was indeed the man, in association with NDR, who invited Frinton over to Hamburg with a view to making the most polished version so far of the famous sketch. He had seen it performed several times before, noted that it had broad international appeal, and was far-sighted enough to realise that a high quality recording might well end up being repeated for years to come.

He therefore persuaded Frinton first to give a live performance at Hamburg's grand and historic Theater am Besenbinderhof, and then, a couple of months later, to film it (for a fee of 4,150 Deutschmarks each for Frinton and May Warden), once again with the actor's stipulation that it would only ever be shown in English. Frinton was keen enough on the plans to have brought his own, much-kicked, tiger skin (and skull) over with him from England.

The broadcast details of the live performance remain a matter of contention, with the high number of unchecked repetitions greatly adding to the messiness of the matter. Frinton's name does not actually get a mention in the German TV listings at the time of the theatrical event, but, given that it was said to have gone out live on 8th March 1963, by far the most likely place where it could have been presented was in a long-running cabaret programme entitled Die Rückblende, which was screened between 8:20pm and 9:05pm that evening.

There are no doubts, mercifully, about the circumstances of the subsequent recording. The filming took place in Studio B of the NDR building in Hamburg-Lokstedt at the start of May. Contrary to some accounts, there was no 'proper' audience present for the session, but, after Frinton and Warden completed an awkward run-through conducted in stony silence, they requested some kind of reaction for the actual recording, and so some of the staff and crew (estimated at between fifty and one hundred in number) responded audibly while the filming went on. The sound of one woman's laughter in particular - Sonja Göth, the wife of the lighting director Viktor Göth - was so loud ('I had a really bad laughing spasm,' she would later explain. 'I couldn't breathe, just couldn't stop') that at one point the studio manager threatened to throw her out, but Frinton was grateful for the encouragement.

This recording, on videotape, would be shown as a stand-alone piece on German TV on 8th June (not July as some sources have it) 1963, as Der 90. Geburtstag. This would be the version that would come to be regarded as definitive.

Buoyed by the success of these multiple foreign enterprises, and the large amount of money they had earned him, Frinton returned home having convinced himself that all of them would simply disappear from view after one or two foreign screenings and no one back home in Britain would be any the wiser.

This belief, however, backfired badly for him, because the Swiss version of the sketch for Nightclub proved so popular with Swiss audiences that the country quickly decided to make the programme its entry in that year's Golden Rose of Montreux Festival. Unluckily for Frinton, the BBC had already elected, in the spirit of public service broadcasting, to feature all of the international offerings for that festival, and so the Swiss entry, complete with his sketch, was duly shown in the UK by the BBC on 9th June 1963.

There were, therefore, not one but five separate recordings of Dinner for One that were made by Frinton, all intended for foreign markets but one, by accident, broadcast in Britain. The BBC screening, however, would mark the end of the sketch's big and small screen exposure during his lifetime, and, indeed, by this time Frinton seemed to have developed something of a love-hate relationship with the routine. On the one hand, he remained grateful for the revenue it continued to generate, along with the much-needed sense of security it provided, but, on the other hand, he occasionally expressed the frustration that 'some people think all I do is Dinner for One'.

The subsequent success of Meet The Wife, therefore, would give him a great sense of personal satisfaction, as well as a feeling of release ('I'd given up hope of anything like this,' he said at the time. 'It was always my ambition to hit the top but I seemed to be stuck in the same old routine of clubs, summer shows and odd TV spots. TV has changed everything'). He would continue to perform the sketch, every now and then, right up the last year of his life (and was even planning, shortly before he died, to film it in Germany once again, but this time in colour), but he would do so now in the belief that it was seen as merely one, rather than the only one, of his comedy achievements.

Following his death, Dinner for One, in his absence, was revived occasionally on the UK stage by other comic performers, including one of his old protégés Clive Dunn, but, after a few years, the sketch, like its star, would slip out of public consciousness in Britain. In Europe, on the other hand, it was only just getting started.

Norddeutscher Rundfunk and its affiliates had been repeating a variety of edited versions of the 1963 recording for years after its first appearance, even reaching audiences behind the Iron Curtain in East Germany, but it was not until 31st December 1972 when NDR's entertainment director Henri Regnier decided, seemingly on a whim, to retrieve this black and white, English-speaking recording from the archives and return it to the screen.

Much to his and many other of his fellow broadcasters' surprise, it somehow managed to capture the imagination of a large portion of the public, and, from that point on, it would be an essential part of Germany's New Year celebrations. They now could not do without it.

It seems that, initially at least, its appeal had something to do with the perception that it embodied, and gently mocked, such supposedly 'typically English' characteristics as their over-reliance on ritual, their stubborn sang-froid and their indomitable eccentricity (as well as, via more of a satirical inference, their continuing concern for qualities and concepts that have long since ceased to exist).

As time went by, however, the charm of the piece would have more to do with the universal humour to be found in the situation, along with the brilliance of Frinton's slapstick performance. Ironically, for a country that had started out laughing at the traditionalism on show, it became their own tradition.

The brief German-language introduction to the sketch itself, spoken by the actor Heinz Piper, explained that there were only two English sentences that the audience needed to know: 'Same procedure as last year, Miss Sophie?' 'Same procedure as every year, James'. Sure enough, these two lines soon became lodged in the public consciousness, and remain to this day as a common pair of catchphrases among German-speaking people.

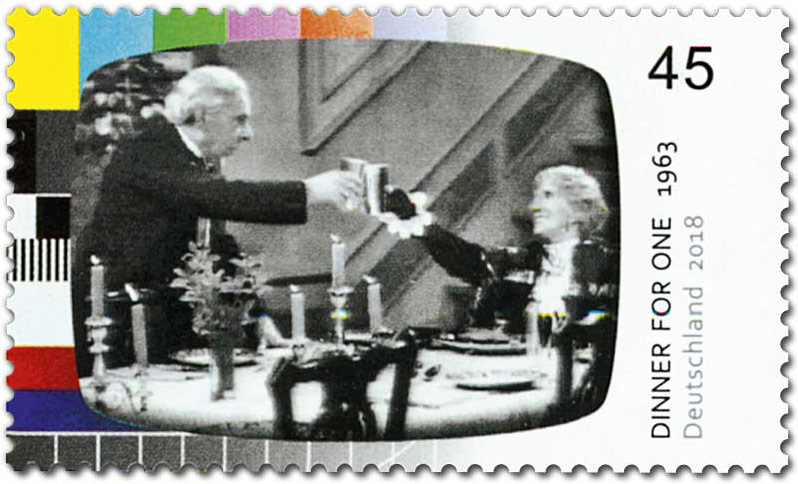

The significance of the sketch grew and grew. Each year it seemed to attract a bigger audience than before, and generate more of a public and critical discussion. In 2004, a record total of 15.6 million Germans saw the sketch, and, even today, the multiple showings add up to a remarkably large annual audience. In 2018, there was even a special postage stamp, issued by the Deutsche Post, hailing it as 'a German TV Legend', and numerous politicians have made a point of quoting it in their speeches.

A similar story has developed in other countries, including Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, the Faroe Islands, South Africa, Greenland, Estonia, Austria, Australia and Luxembourg, where the sketch has acquired the same kind of cult status as an annual New Year's Eve event. It has also inspired a wide variety of international revivals, revisions and 're-imagined' performances.

There has been a colourised version; versions in regional dialects like Low German, Swiss-German and Hessian; a Dutch language version (featuring an actor who appears to think 'acting drunk' means 'looking as if you have two prosthetic legs'); a (quite awful) Danish parody version (80 års fødselsdagen) in which Miss Sophie's absent friends are present again; the children's Erfurt-based public TV station KI.KA's Dinner für Brot, which features a puppet of James shaped like a loaf of bread; a rather endearingly silly LEGO version; and in 2011, another parody was produced for the German broadcaster ARD, this one entitled 'The 90th euro rescue summit, or euros for no-one,' featuring the superimposed heads of German Chancellor Angela Merkel as Miss Sophie and French President Nicolas Sarkozy as James, complete with their invisible guests - the Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou, former Spanish PM Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero and then-British Prime Minister David Cameron ('This is what happens at every Euro rescue summit, whether or not anyone else is there,' the narrator remarks at one point. 'It is just these two doing everything themselves'); and in 2016, Netflix produced an advertising re-make in which the guests of Miss Sophie were the Netflix series characters Frank Underwood (House Of Cards), Pablo Escobar (Narcos), Saul Goodman (Better Call Saul) and Crazy Eyes (Orange Is The New Black). There is also a decidedly risk-laden drinking game, in which viewers have to try to keep up with James as he staggers from one gulp to the next.

Britain, however, remained strangely immune to all of this cultural intoxication. In 2004, for example, a BBC spokesman told a stunned reporter for Der Spiegel magazine that not only were there no plans to show the sketch, but also that he had never even heard of it.

It would not be until 2018 that the British finally got to see one of their most celebrated comedy sketches again on the TV screen. The 1963 recording premiered at a slapstick comedy film festival in Scotland in November of that year, and then was shown on New Year's Eve on the Sky Arts channel. It briefly aroused some curiosity in the media, and was seen by a reasonably large audience for the station and the slot, but it failed to spark any continental-style cult - prompting a baffled Der Spiegel to declare that the question as to why this British comedy classic continues to be embraced by just about everyone except the British is 'one of the last unsolved questions of European integration'.

While Dinner for One may now strike our neighbours as more apt than ever after Brexit, it seems unlikely that we, as a nation, will belatedly embrace it as a tradition of our own. It would be a pity, however, if most of us go on missing out on enjoying, a least once every now and again, this historic little sketch, because it is a genuinely entertaining piece of comedy.

It is particularly worth watching in order to see Freddie Frinton at work, as he was a master of what is now the fast-disappearing art of physical comic acting. While you watch and laugh at him raising a glass to the memory of Sir Toby, Admiral von Schneider, Mr Pommeroy and Mr Winterbottom, therefore, you may well want to raise your own glass to the memory of him.

Happy New Year, Freddie.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more