The life and times of Frankie Howerd's toupée

What a strange job it was, being Frankie Howerd's wig. It had to rest there on top of his head, doing its best to seem subtle and discreet, whilst its owner regularly blew its cover by scratching it, flipping it and skewing it. If it could have moved of its own volition it would surely have quit and flounced off down the back of his neck.

It is still going strong today, coming up to three decades after its famous owner's death, and, like some unfortunate Dickensian orphan, has survived myriad forms of mistreatment. Having been buried and exhumed, at least once, as well as perched on a teapot for public perusal, stuck on top of a statue and even threatened with being sold into slavery, the hairpiece is currently located somewhere in Somerset, at long last hidden from the limelight.

The story of Frankie Howerd's wig stretches all the way back to the early 1950s, when the comedian started losing his own hair. Ever since the early days of his success on radio, Howerd had been suffering from a condition known formally as 'alopecia areata' - and informally as the gradual loss of hair from certain areas of the scalp.

Baldness, back then, was deemed a bad thing by the showbusiness big-wigs. These days, of course, hairlessness is not only accepted but in many cases considered a positive fashion statement, with even relatively hirsute entertainers adopting the completely shaven look rather than settling for a slightly receding pate.

It is teeth that makes performers insecure in these over-bright and high definition days, with any dental imperfections covered up by luxury lavatory-like slabs of gleaming white porcelain. Celebrities today are basically wearing teeth toupées.

Back in the fifties, however, it was baldness that required covering up. Many comedians were thus forced to hide their hairless heads: Jack Benny, George Burns, Steve Allen, Harpo Marx, Groucho Marx, Arthur Askey, Cyril Fletcher, Jimmy Jewel, Max Miller - the pressure was always there to make oneself stay looking 'youthful' and bursting with trichological vitality.

Howerd's own adoption of the toupée, though far from ideal, was an inevitable result of his amour propre. He would never feel particularly happy with it, but he knew that he would have felt unbearably unhappy without it.

It was not that he was entirely blind to his obvious facial imperfections (the overall effect of which, in the words of one critic, made him look like 'Simple Simon with mumps'); it had more to do with his slightly exaggerated estimation of his overall physical charm, as well as his determination to preserve his reputation as an irrepressibly vivacious comic performer. Just when he felt that he most needed to prolong the sense that came from the supposedly careless ebullience of youth (he had already taken to cutting as many as five years off his 'official' age), he found that he had to fight against his prematurely aged physical appearance.

It represented, to him, yet another secret weakness, yet another reason to feel vulnerable and to worry, and he had already accumulated more than enough of those kinds of neuroses. The effect was to make him more edgy and depressed than ever, plagued by bouts of the sort of nervousness that made his mind feel, in his lowest moments, like 'a disintegrating jigsaw'.

Losing his hair seemed like the cruellest stroke of luck at the time. He had already been forced to fight so hard to make any mark in showbusiness. He had failed audition after audition, he had been dismissed by a succession of theatre managers for failing to conform to the old-fashioned stand-up norm, and he had struggled to find anyone who understood and appreciated his new, openly flawed and informal, style of performing.

Now that he was finally established as a star, he found that his hair was falling out. It felt like one more way that fate was conspiring against him.

He had disguised the condition for a few years by 'fluffing-up' his thinning locks to fashion a 'just-been-electrocuted' style of quiff, but, by the fifties, he had no choice (seeing as he could not bear to be seen in public with a balding head) but to start hiding the damage under a hairpiece.

He would actually end up having four toupées specially made, of varying styles and prices, but, throughout the rest of his life, he would seldom wear any other than the first one. It was made (at the cost of £35 - about £925 in today's money) by Stanley Hall, who had known Howerd since their days together working in forces entertainment during the war, and who was by this time the co-owner (alongside his friend, Noel MacGregor) of Wig Creations of London.

Specialising in bespoke tonsorial designs for showbusiness people and productions, his clients already included the likes of Mae West, Noël Coward, Katharine Hepburn, Marlene Dietrich, Rex Harrison, Elizabeth Taylor, Ray Milland and Vivien Leigh, as well as innumerable theatre, television and movie companies all over the world (he would later supply all the wigs, for example, for the Hollywood epic Cleopatra), and he could be relied upon to produce high quality hairpieces swiftly and very discreetly. As improbable as it sounds today, the hairpiece that Hall designed for Howerd was, in its original state, actually rather impressive.

The problem was that Howerd seemed as incapable of mastering basic wig management as he did the maintenance of his clothes. As his long-term partner, Dennis Heymer, would tell me: "Frank could put on the most immaculate £1,000 Savile Row suit and twenty minutes later it was a total mess. That's just how he was. Whatever clothes I'd get him, no matter how well they fitted, he'd have them creased and pulled this way and that in no time at all like a sack of spuds. And it was the same with his hair."

Stanley Hall - a normally very ebullient man with a bright bow tie and a beaming smile - would do his best to coach Howerd as to how to put the hair on and how to take it off, how to use gauze and glue without any seams being seen, and how to keep the real human locks in the very best condition, but he soon became exasperated by the sight of what his client was doing to his latest creation. Screams, gasps and groans were not uncommon sounds during the first couple of post-fitting check-up sessions at Hall's George Street salon. In the end he simply gave up, and, unlike his countless other designs, he would in future flatly deny any ownership of the sorry thing that now sat so limply on top of Frankie Howerd's head.

From that point on, it seems that Howerd was the only one convinced that it was practically impossible to see the join. He never did learn how to fix it properly or look after its proper shape, and yet somehow he still felt that he was getting away with a suitably 'natural' effect.

One of his first opportunities to 'test' it was when he made the latest of his regular trips abroad to entertain British troops. He was relieved that, in spite of the odd feeling of aeration when there was a breeze, the toupée did not get a single audible heckle from any of the soldiers. Ignoring the fact that the troops were now on their best behaviour when a celebrity came to see them, Howerd returned home convinced that he was fully in control of Hall's creation.

Those who knew him colluded with him without a word being said; they knew how sensitive he was about his hair loss, and so they did their best to behave as though the problem had now been solved. Even fellow comedian Max Bygraves, one of his oldest and most trusted confidants, was obliged to pretend not to notice every time a sudden gust of wind caused the hairpiece to hover slightly above Howerd's head, and plenty of other friends and colleagues found it similarly hard, at least at first, not to stare.

None of this really mattered, of course, because he was such a brilliant comedian. His whole act was about his all-too-human imperfections. He stuttered, he muttered, he appeared to forget what he was saying, he complained about the heat or the cold, he grumbled about his health, he moaned about his ill-fitting clothes - what was a bad wig between friends? He was so gloriously vulnerable, and so delightfully funny, that the faulty hairpiece just came to seem like one other comic ingredient that made us laugh at him, and with him, as one of us. It was a little too much, but only just.

In later years, however, when the much-abused wig had come to resemble an elderly outstretched stoat, the effect would be even more risibly obvious. "He used to scratch the back of his head when he was talking to you sometimes," recalled the writer Barry Cryer, "and the hairpiece would go up and down like a pedal bin".

Other colleagues would make similar observations. Many were particularly struck by the fact that they had never before seen a toupée that came with its own dandruff.

There were never any wig-free days or even evenings. It was as if he needed to convince himself, as well as everyone else, that what was up on top belonged on top. Even his closest friends were thus expected to ignore it even when they could see the glue dripping down his sideburns when he had, yet again, failed to follow the proper procedure.

Two of his most famous female friends - Elizabeth Taylor and Bette Davis - were privy to his secret, and, as experienced wig-wearers themselves, they tried in vain to teach him, belatedly, the right way to handle the hair. Davies even bought him an elegant-looking teapot for the task, telling him it could be used to gently steam the toupées to give them a little lift. True to form, however, he continued treating them with his usual casual clumsiness.

"We used to go on holiday to the South of France with him and Dennis," Cilla Black would recall, "and I would have sleepless nights worrying about that wretched wig, and how he would cope in the sea. Frankie would wear the wig, put a beany hat on top, and do the breaststroke very elegantly, always keeping his head above water."

He would sometimes revert to one of his other, cheaper, wigs when he feared that exposure to inclement weather, or a sauna, or some kind of slapstick-related special effects in the studio, might damage his favourite fake (this had also happened when, in an attempt to 'cure' his depression at the start of the Sixties, he underwent several sessions taking LSD under the guidance of a psychotherapist - he had heard scare stories of some follicly-challenged patients tearing off their toupées while under the influence of the drug, so he opted for one of his 'back-ups' with rather more glue than usual). This would happen even when, through further misuse, these 'reserve' toupées had become so unsightly that they looked as though a Jack Russell had been playing with them for several days in its basket.

The 'emperor's new hair' routine was bad enough during leisure time, but it was growing increasingly farcical when he was at work. Both in the theatre and in the film or television studio, it became discreetly obligatory for people behind the scenes to find tactful ways, when the role required a wig, to pretend that the star was not already wearing a wig.

David Croft, for example, was astounded by Howerd's touchiness about his toupée when they worked together in 1970 on the sitcom Up Pompeii!. "I mean, we all knew he wore a wig," the director would tell me. "I knew, all the crew knew, everyone knew. It was obvious. He'd come in with this ridiculous THING on his head, and you'd just avoid looking at it. But we'd had this wig made for him for the show - much better-looking than his own, of course - but the poor people in the make-up department had to go through this ridiculous routine each morning of pretending that his wig was his own hair, and they'd have to put our wig on top of his wig - which was actually quite tricky, especially when it came to taking it back off. He must have been boiling under both of those wigs but that's what we had to do every single time!"

Many years later, the writer and broadcaster Danny Baker was another who got to witness at first-hand the plight of the ageing hairpiece when, in the 1980s, its even more elderly owner turned up to make an appearance on an early evening TV magazine show. Baker would recall in his memoir, Going Off Alarming, that as the comedian sat in the make-up room, he noticed that the wig was looking even more unhinged and listless than usual - "like the Titanic after all the rockets had been launched" - but he, like just about everyone else, knew that the wig was not supposed to exist, so he pursed his lips and said nothing. Unfortunately, however, the young make-up artist was one of the few who had somehow missed that particular memo, and so, purely out of professional courtesy, she asked the great man: 'Do you want me to tease the wig out a little, Mr Howerd?'

The reaction was positively explosive. 'WIG?' he shrieked, his voice shooting up like a whistling firework. 'WIG? What are you talking about, you blessed creature? Wig? I've never had that from a make-up person in thirty years. How dare you! I've got a good mind to go straight home!' He then marched out of the room, growling multiple complaints as he departed.

'But it is a wig, isn't it?' asked the distressed make-up artist, still unsure of what had just happened. 'I think,' said an older and wiser colleague nearby, 'it's always safer to refer to it as "hair", June...'

In Howerd's final few years, when what was left of his real hair around the back and sides was grey and wispy, the toupée looked as though it had been abandoned on his own head, lying there in helpless isolation like a gill-flapping fish stuck on a sandbank. Parts of it were still chestnut brown, while other parts looked darker or lighter, as if he had taken to touching the toupée up with a selection of coloured felt tip pens. Still, however, the pretence proceeded as usual.

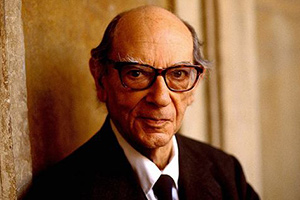

The only time that the wig stayed off for any significant length of time was close to the end of his life, when, following a collapse, he was receiving treatment in the intensive care unit of the Harley Street Clinic. One of the few visitors who were allowed to see him in that vulnerable state told him that, when he also had his glasses on, he looked like the eminent historian of ideas, Sir Isaiah Berlin - which, for the first and only time in his life, seemed to make him quite happy to be hairless. (As I knew Isaiah Berlin, I later told him about Howerd's reaction, and Berlin seemed as delighted as the comedian was with the comparison: 'Oh, what a double act we could have been,' he laughed, clapping his hands together.)

Frankie Howerd died from heart failure in 1992, at the home - Wavering Down House, a pretty, pink-walled cottage in the village of Cross near Axbridge in Somerset - that he had shared for so many years with Dennis Heymer. Dennis, broken-hearted, kept two of Howerd's wigs (and gave away the others to a couple of Frankie's close friends), and buried the best of them under one of the beautiful rose trees in their garden, where he would sit and stare and remember. That seemed a just end for the much-maligned hairpiece of a much-loved partner.

That, alas, was not the end of the story. Living with Heymer now was Chris Byrne, a former nurse and occupational therapist. An extremely divisive figure among Howerd and Heymer's network of friends, Byrne had his own ideas as to how the great comedian (and his hairpiece) could and should be remembered.

Byrne, who first met Howerd and Heymer in 1983 in a North London pub when he was a troubled teenager, had been taken under their wing and given support in the years that followed. After Frankie's death he started describing himself either as Dennis's 'adopted son' or else as his 'partner'. Like Dennis, he was an alcoholic, sometimes recovering and sometimes lapsed, and their union ("It's not a romantic relationship," Byrne would say, "but a caring one") developed to the point when, in 2005, they entered into a civil partnership.

As Dennis's health continued to decline, Byrne, controversially, started assuming far greater control of Howerd's home and legacy. Some saw his actions as being primarily philanthropic, while others considered them motivated more by a powerful desire for self-promotion (and, to be fair, the consensus was probably somewhere nearer the latter than the former opinion), but what is surely true is that, at least in terms of taste, some of his subsequent decisions left a great deal to be desired.

In 2006, for instance, Byrne persuaded the ailing Heymer to allow him to open up Wavering Down House as a tourist attraction during the summer months, both to celebrate Howerd's life and raise money for a number of charities. If that move succeeded in attracting a fair degree of praise, what he did with Howerd's most personal possessions more commonly elicited anger and even revulsion.

Nothing, it seemed, was deemed too private and personal by Byrne when it came to choosing what to place on public display. Frankie's much-cherished OBE was not available, as Byrne had already raffled it away for 'various charities' the previous year, but most other things were still up for grabs, and he certainly grabbed them. He not only included, for example, Howerd's false teeth, x-rays and truss, but he also dug up the wig and placed it ready for inspection on Bette Davis's vintage teapot.

Visitors paying the £2.50 admission were taken on tours of the house, and were allowed to scrutinise, and sometimes even touch, the famous toupée, which, when the weather was nice outside, he would leave to 'sunbathe' on one of Dennis's garden statues ('Smell that,' Byrne would sometimes say, holding the hair close under someone's nose. 'It still smells of his body odour'). The level of intrusion would have horrified Howerd, but it seemed that Byrne's regular invocations of 'charity' kept winning out over concerns for simple decency and respect.

Dennis Heymer passed away in 2009. He had told me on several occasions, during his pleasantly rambling telephone conversations over the years, that he had asked Byrne to slip Frankie's favourite toupée into his jacket pocket when he died, so that he could be buried with it in his grave. Byrne, with sad predictability, failed to do so, and it remained out on display for the pleasure of the next procession of strangers.

The following year he changed his mind. Having already toyed with the idea of turning the house into a drug and alcohol rehab centre, he then decided to put the house and all its contents, including the wig, up for sale (along with the option to buy a thirty-three per cent share of the Howerd estate). The initial asking price was £800,000 for the property, and an additional £600,000 for the memorabilia; once neither price was met, the house eventually went for about £450,000, and many of Howerd's possessions were sold at auction.

"He was very bossy," Byrne said at the time about his late benefactor. "He was also very private. He'd bump into the neighbours and he would want to know everything. But as soon as they asked something about him - even something like 'Will you be going up to London soon?' - he'd tell them to mind their own business." What a great shame that Byrne did not take the same advice himself.

Once the house was sold, he did move on, with his new partner, but he still couldn't quite leave the memory of Howerd alone. He even tried touting some extremely dubious-sounding 'secret diaries' around to various publishers, as well as selling yet more of his remaining memorabilia.

The toupée, however, would end up outliving Byrne, too. He died in 2017, aged just fifty-one, and the new custodians of Wavering Down House, very wisely, decided, at long last, to grant this most over-exposed of wigs a well-earned retirement.

It had served Frankie Howerd very well. He might have made it, and as a result himself, look a little foolish on quite a few occasions over so many years, but, in spite of all of those tonsorial travails, it had always made its owner feel a little better about himself - and that, in the great scheme of things, is surely all that matters.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreFrankie Howerd: Stand-up Comic

The most authoritative biography of Britain's most subversive twentieth century clown from celebrated biographer Graham McCann, author of Dad's Army: The Story Of A Classic Television Show and Morecambe & Wise.

The rambling perambulations, the catchphrases, the bland brown suit and chestnut hairpiece: such were the hallmarks of a revolution in stand-up comedy that came in the unique shape of Frankie Howerd. His act was all about his lack of act, his humour reliant on trying to prevent the audience from laughing ('No, no please, now...now control please, control').

This new biography from Graham McCann charts the circuitous course of an extraordinary career - moving from his early, exceptional, success in the forties and early fifties as a radio star, through a period at the end of the fifties when he was all but forgotten as a has-been, to his rediscovery in the early sixties by Peter Cook. Howerd returned to television popularity with Up Pompeii!, which led to work with the Carry On team. In his last few years he became the unlikely doyen of the late eighties 'alternative' comedy circuit. But his life off-stage was equally fascinating: full of secrets, insecurities (leading at one point to a nervous breakdown) and unexpected friendships.

Graham McCann vividly captures both Howerd's colourful career and precarious private life through extensive new research and original interviews with such figures as Paul McCartney, Eric Sykes, Bill Cotton, Barbara Windsor, Joan Sims and Michael Grade. This exceptional biography brings to life an exceptional British entertainer.

First published: Monday 18th October 2004

- Published: Monday 4th July 2005

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- Pages: 384

- Catalogue: 9781841153117

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 25th February 2016

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- Download: 1.22mb

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Fourth Estate Ltd

- Pages: 384

- Catalogue: 9781841153100

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.