Who you gonna call? When Ernie Wise launched the mobile phone

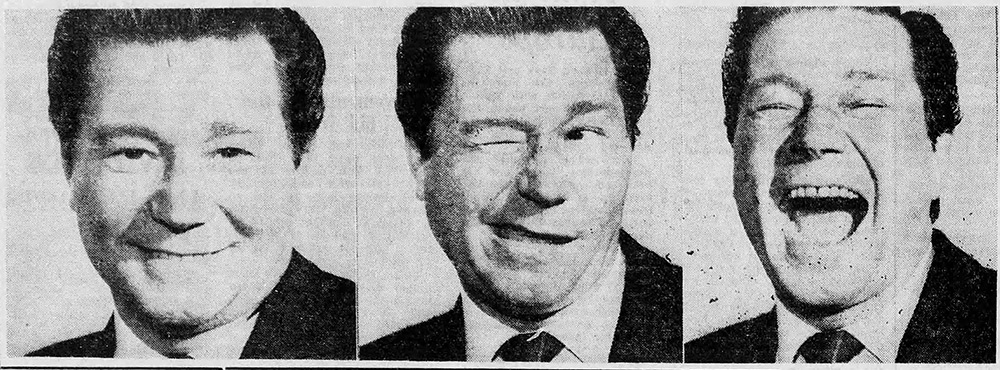

Let's look back, forty years, to the New Year's Eve of 1984: the clock is ticking, Big Ben is building up to its bongs, and, after the stroke of midnight, that fancy new thingummyjig, the mobile phone, will soon be eliciting its first excited 'Ahoy-hoy'. Who is going to make this historic call? That's right: Ernie Wise.

It was not actually the first time that the United Kingdom had chosen a comedian to launch some new piece of technology. It had done so before, on 27 June 1967, when Reg Varney, of all people, was selected to make the historic initial withdrawal from the world's first voucher-based cash-dispensing machine.

He of the brilliantined barnet and the boyish smile, Varney, who had become a household name earlier on in the Sixties through his regular role in the popular sitcom The Rag Trade, was now riding his second wave of fame as one of the stars of another very successful BBC sitcom called Beggar My Neighbour, playing a reassuringly down-to-earth but very well-paid fitter named Harry Butt. It is not known why, exactly, the bosses of Barclays chose him, rather than anyone else, to launch its brave new age of banking, but it probably had something to do with his current image as an eminently amiable 'working-class man made good'.

Varney was hardly primed for publicising such a major new national initiative. His past promotional activities had been limited largely to lending his name and image to ads for Brylcreem and beer. Like many performers from that era, however, he had more than enough painful memories, struggling around the post-war Variety circuit, of begging banks for help ('I 'ate you, Barclays!'), to make the prospect of one of them actually paying him for his own assistance sound quite irresistible, and, besides which, a recent minor heart attack had left him considerably more self-conscious about protecting his and his family's financial future.

'Get paid for pulling some money from out of a wall?' he asked himself. 'Yes, please!'

The cash-dispensing machine had actually been invented a couple of years earlier by a sharp-witted Scot named John Shepherd-Barron, then managing director of the banknote printers, De La Rue. Having arrived one afternoon at his own local branch just too late to cash a cheque, he had come up with a practical solution to such frustrations later that evening. Relaxing in a hot bath at his home, he pondered the possibility of a vending machine that could supply money instead of crisps, nuts, chewing gum or chocolate, and realised that, if he could make it work, it could prove to be revolutionary.

He took the idea to the Chief General Manager of Barclays, Harold Darvill. The two men sat down together, drank a glass or two of pink gin, and talked the matter through. Darvill, reflecting on the potential labour power he could save in all of his many branches, needed little persuasion before committing to the project. 'If you can build them', he told Shepherd-Barron, 'I'll buy them'.

Other banks, once news of the move slipped out, soon started exploring the same basic idea themselves. The Westminster was thought to be planning its own prototype developed by the security firm of Chubbs, while the Midland, Lloyds and the National Provincial were also reported to be discussing how, when and where to follow suit. Barclays thus now found itself in a race, and, determined to win it, the bank accelerated its schedule to ensure that its own version - the De La Rue Automatic Cash System, as it was called, or DACS for short - would still be first to cross the financial finishing line.

Described at the time as 'Britain's first robot mini-bank,' it was announced in March 1967 that six were set to be installed by Barclays in selected branches scattered outside London for a period of testing during the latter half of the year, but, with the pressure to deliver first still mounting, the original model was brought forward and readied for action at the Barclays Bank building at 20 The Town, Enfield, in Middlesex. The smartly-attired Sir Thomas Bland, then deputy chairman of Barclays, was present there, along with a handful of police constables and several print, radio and TV journalists and photographers and a large crowd of local members of the public, to witness the historic occasion.

The rumour in circulation was that the relatively modest Enfield location had been chosen mainly because, having a much lower profile than the bigger metropolitan branches, the coverage of any cock-up would be easier to control, and Barclays were certainly taking no chances regarding the execution of this major new mechanical transaction - even, it was alleged, going to the trouble of having a diminutive employee lurk on the other side of the wall, ready to push through some money manually if the actual machinery malfunctioned at the key moment.

Reg Varney was not aware of any of this. In fact, he seems to have been rather unsure of what exactly was going to happen.

The fact was that a quick, and very discreet, rehearsal had been performed the previous day by a local employee, and (according to some recollections) it had not gone very smoothly. While several engineers worked to fine-tune the process during the hours that followed, it had been decided not to worry the guest celebrity with any warnings about the possibility of anything going wrong in front of the public and the press.

On the big day itself, therefore, Varney (dressed casually in the cabby-chic attire of a cardigan and white flat cap) simply arrived, smiling and waving, and was guided by Sir Thomas into position to be pictured doing the historic deed - half an hour after, it was pointed out, all the banks had closed. There was no such thing as a debit card for the star to use - that device would only come into being at a later date. He was simply given his own special four-digit number on a piece of paper and handed a special cheque (impregnated with carbon 14, a mildly radioactive substance), along with a simple set of instructions as to how to proceed.

In his prestigious position as 'Barclaycash's' first customer, therefore, Varney, reported one newspaper in tones of breathless wonder, 'put a signed voucher into a drawer in the machine, tapped out his personal code number on a keyboard, and out popped a drawer containing the money'. The star held the crisp new £10 note aloft like a trophy, the crowd cheered and applauded, the photographers snapped, and the event was over. British banking had entered a new age of automation.

The launch itself, in spite of its cheerful celebrity host, did not actually prove to be especially effective in encouraging ordinary customers to start following in Reg's footsteps and drawing out their cash from machines. Many members of the public, still concerned about security issues, would continue to prefer a personal form of service at their banks for a long time ahead, and any subsequent gradual change in habits arguably had far more to do with banks reducing their opening hours, rather than the power of any new advertising initiatives.

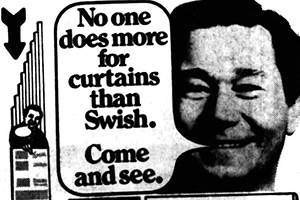

Varney himself experienced no great change either - other than receiving a sizeable deposit in his own savings account - after his participation in such a high-profile project. His next extra-curricular gig would see him serve in a marketing campaign as the public face of a 'functional window coverings' company ('No one does more for curtains,' he was pictured as saying, 'than Swish'), and his personal involvement in changing the way that his fellow citizens obtained their cash soon faded from most people's memory.

The idea of using comedians to capture the attention of a mass consumer audience, however, remained in the mind of those looking for ways of popularising technological innovations that might otherwise have alienated a public that traditionally was wary of change. Comic figures, reasoned the marketing men and women, were uncomplicated, unthreatening and fun: if you wanted to simplify something that might otherwise seem intimidatingly intricate and/or odd, and assuage the nagging nerves of the technophobes, then you could do worse than hand the campaign over, at least in spirit, to a much-loved comedian.

This seems to be how Ernie Wise, for a while, became one of the industry's go-to guys for launching new gadgets. It would always be an unlikely collaboration - Wise, outside of show business, was not known to be a particularly worldly person, having spent precious little time in school during his years as a precocious child entertainer, and even as an adult he never showed much curiosity about things beyond the walls of the television studio (and fancy new gadgets, such as clunking digital watches, were gleefully mocked by Eric and Ernie on their shows) - but his huge popularity as one half of Morecambe & Wise, combined with his shrewd business sense (apart from Eric, his mother used to tell him, 'your best friend is your wallet'), made him an eager and surprisingly effective ambassador.

His involvement in touting technology had started in the mid-1970s, when he and his partner were picked to promote various new electronic items for the companies Ekco and the Trio Corporation. These were quite modest affairs, aimed mainly at selling new models of TV and hi-fi sets, but financially they certainly whetted the appetite for exploring further commercial opportunities once the pair left the BBC (which, due to its own advertising restrictions, had already blocked a number of lucrative options) for ITV later on in the decade.

Ernie ventured rather deeper into the white heat of new technology in 1982, when the US consumer electronics company Atari chose him and his partner Eric to front the British sector of a multi-million pound international advertising campaign for its new range of home video games. Hoping to widen the age bracket of its usual consumers, as well as expand its market share overall, Atari used the reassuringly traditional and never-nerdy Eric and Ernie to bring the brave new world of modules, flickering screens, gobbling digital gobs and tinny little beeps, peeps and pops to the broader British public via a succession of high-profile television, cinema and print advertisements.

Viewers were thus confronted by the unexpected sight of a flat-capped Eric eschewing his old football rattle and empty paper bag and suddenly announcing: 'Right - who's for Atari?' The two of them then sat down together on their comfy suburban settee, competing excitedly to see which one could come out on top at such games as Pac-Man, Space Invaders, Missile Command, Super Breakout, Yars' Revenge, Berzerk and Haunted House ('That's where the action is!').

In one ad, for example, they are joined in their flat by the languid then-West Ham midfielder and expert dead-leg diagnoser Trevor Brooking, who cannot believe his luck in happening upon two such technologically-advanced northern fifty-somethings:

TREVOR: I see you play Atari!

ERIC: Now and then, Mr Brookun.

ERNIE: Brooking.

ERIC: Oh. Do you fancy a game of Pele's Soccer?

ERNIE: No, he's not interested in -

TREVOR: I'll have a go.

[Trevor proceeds to dominate the game.]

ERIC: Forty-love - he's a bit good, your Mr Bootin.

ERNIE: I've told you - it's Brooking!

ERIC: Well, whatever his name is - ever thought of playing for Luton Town reserves, youngster?

TREVOR: No!

Atari - which ended each ad with the slogan, 'Simply more fun and games' - was by all accounts delighted with the impact Eric and Ernie had made, with a massive increase in profits that Christmas, followed by a much-desired spike in sales to a more mature demographic over the course of the next few months. While neither Morecambe nor Wise would ever be caught having a private play of Pac-Man, both of them, at a time when they were easing down on their TV commitments, were similarly pleased at the additional personal financial rewards that the campaign had delivered.

Ernie Wise's next, and most momentous, promotional role for new technology would prove to be a bitter-sweet experience for him, because it took place just a matter of months after the shattering loss of his partner. Eric had died on 27 May 1984, at the age of fifty-eight, following a solo performance on stage for charity. The heartbroken Ernie, as a consequence, suddenly found himself not only without his friend and partner but also, he feared, a viable professional career.

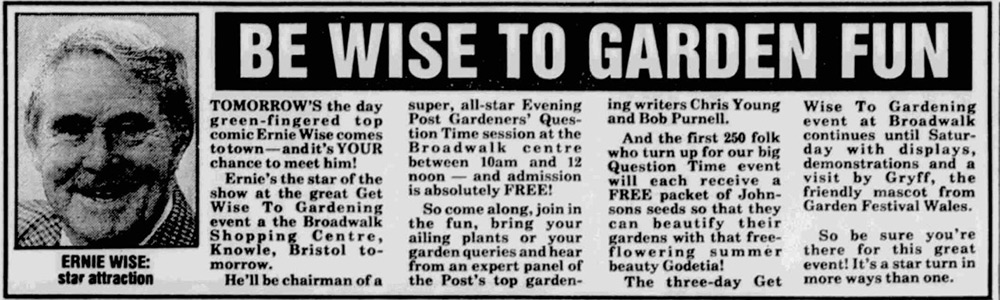

Anxious not to be forcibly retired by those in the industry (and, as he knew all-too well, there were many) who seemed disinclined to see him as anything other than one part of a much-loved but now defunct double act, the former juvenile song and dance solo star ('England's answer to Mickey Rooney,' as, long before scriptwriter Eddie Braben's gently teasing revival of the phrase, he really had been known back in his early teens) started looking for ways to remain in the public eye ('You have to carry on, don't you?' he said at the time. 'I don't want to disappear'). He thus started accepting pretty much anything that he was offered in the months that followed, including guest spots on TV panel shows and some radio work, in addition to a one-off appearance in a US comedy called Too Close For Comfort, and he also began talking to his old friend Philip Jones at Thames TV about the possibility of starring in his own sitcom as well as hosting a talent show, and (in spite of the fact that, by his own admission, he disliked getting his hands dirty working the soil and employed his own gardener to do it for him) he even agreed to do a ghost-written gardening column for a Sunday tabloid newspaper (which in turn would lead, even more improbably, to him hosting a series of Get Wise To Gardening public events up and down the country).

He was also open to any offers to help promote what he considered to be good causes. In September, for example, he fronted the 'Think British' campaign (launched by the Confederation of British Industry with the aim of encouraging consumers to spend more on domestic products), dressing up in workman's clothes and pasting posters up at Waterloo Station. He followed that venture by teaming up with a dog called Pippin to film an anti-litter ad for his local Keep Berkshire Tidy Group, then toured the country to promote the latest annual Poppy Appeal, and did some work for the RSPB, while also supporting (in memory of Eric) a Government-backed campaign to combat heart disease.

It was during this intense period of diverse activity that the chairman of Vodafone, Ernest Harrison, got in touch to ask Wise, who was an old acquaintance, to help launch its mobile phone and, with it, Britain's first cellular network. Ernie was happy to accept. Like most of the population at that time, he did not know anything about mobile phones, let alone cellular networks, but he was still accepting more or less anything that came his way during this strangely disorienting time.

The mobile phone in question was the Transportable Vodafone VT1. Weighing about 5 kilos, and costing a whopping £1,650 (roughly £6,700 in today's money), it was powered by two six-volt gel-cell batteries that took ten hours to charge, and provided a talk-time of approximately forty-five minutes (at a tariff of thirty-three pence - about £1.34 these days - per minute).

Many years later, some nostalgic wags at Vodafone (originally a start-up from inside the wider Racal defence and electronics company) would jokingly describe the item as being 'the size and weight of a small dog and as slim as a loaf of bread,' with sixteen rubber buttons 'that go in when you push them' and a 'massive two-inch display'. At the time, however, their real boast was that it was a 'magical product' that will 'change the world for ever' through a 'talking revolution' (a series of Saatchi & Saatchi ads, featuring some brash-looking Ferrari-driving businessmen, would sport the slogan: 'You can be in when you're out').

No public announcement was made over the festive period that the fancy new phone was going to be dialled into action during the early hours of the first day of 1985. The reason for that was, as it was already known within the industry that Vodafone had a license obligation to open service before 31 March 1985, the company wanted to take its rival BT by surprise. The real date of the launch, therefore, along with the identity of the first celebrity caller, would only be revealed to a few selected sources during the final couple of hours on New Year's Eve.

On the day itself, therefore, a small crowd had only just started to form close to the venerable Dickens Inn at London's St Katherine's Dock when none other than Ernie Wise arrived in a nineteenth-century mail coach (symbolising, supposedly, the continuing history of innovative communications technology). Dressed in a Victorian coachman's costume, he emerged from the carriage to wave his top hat at some fairly bemused members of the public - the 'retro' theme had not really yet been clearly explained - and then launch the next telephonic revolution.

After saying a few scripted words about what an exciting moment it was, Wise announced that he was going pick up the great big brick of a 'mobile' phone, press the large rubber buttons, and call up the Vodafone headquarters (a very modest affair at the time that was based above a pub and just behind a curry house) in Newbury, Berkshire. It was never reported what he actually said during that historic conversation, beyond: 'Hello, it's Ernie Wise here!'

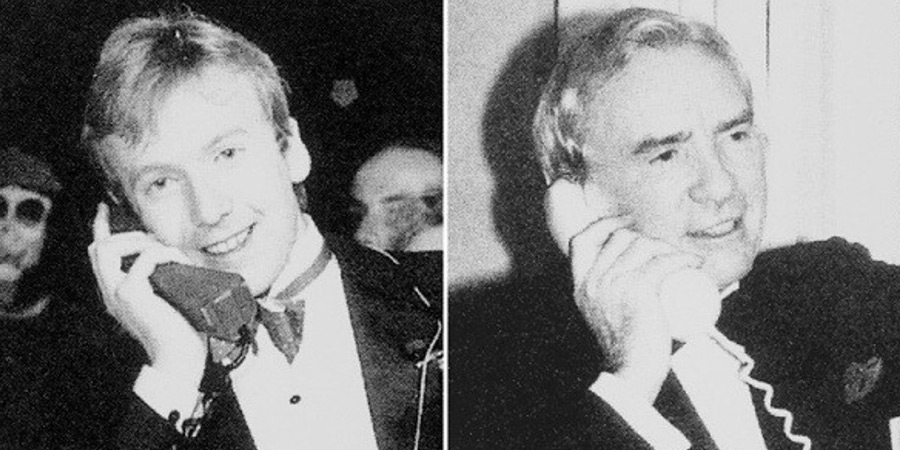

What Wise (along with the assembled crowd and various media representatives) was oblivious to at the time was that the first actual call had already been made. In addition to some trial calls that were made during December, we now know that Michael Harrison, the son of Ernest Harrison, had previously punched-in the initial number during the first few seconds of that morning, having crept out of his family's New Year's Eve party at their home in Surrey and travelled to London to 'surprise' his father, as Big Ben was bonging, with a call ('Hi, Dad - it's Mike!') from within a mass of revellers gathered together along the Thames Embankment.

As he later recalled: 'The setting was quite dramatic, standing by the statue of Winston Churchill in Parliament Square surrounded by curious New Year's Eve revellers. I think neither they nor I had even seen a mobile phone before, let alone used one. It was just like a normal telephone call - at least that's my recollection. I thought it might somehow sound quite different talking to somebody on a cellular network so it was a bit of a surprise that everything was so clear'.

Harrison Snr, in truth, could not have been particularly surprised to receive the call, seeing as he had a photographer standing nearby to capture the moment when he picked up at his end and said 'Hello' to the brand-new age of consumer telephonic mobility. Several champagne bottles were then popped and much celebrating was had by all of the assembled happy Harrisons.

None of this, however, impinged at the time to spoil the moment for Ernie Wise. Once he had completed his own call, he stood, smiled and leapt about in celebration for the cameras. He was, by this stage, a practiced hand at putting on a good promotional show.

While the choice of the first morning of a new year made sense for such a sight in terms of its symbolism, it did not actually make too much sense in terms of generating media coverage, for the simple reason that even the precious few journalists or photographers alerted to the event had been particularly keen on shaking off their hangovers and staggering out into the cold January air to cover the story. The result was that Wise's (and the phone's) dramatic public appearance failed to make a splash on the pages of the national newspapers, and those initial rings, as far as most of the British public were concerned, were left stuck on silent.

It did not really matter - the demand for the product (at least among businesses) was already so great, by the standards of the time, that more than two thousand orders had been taken by the company before Ernie had even flexed his muscles and lifted the device up with both his hands. Industry forecasts as to the likely number of subscribers during the following twelve months promptly shot up by more than twenty per cent.

Vodafone's 1985 monopoly of the UK mobile market, however, would last just nine days before BT Cellnet (the forerunner of O2) rolled out its rival service. By the end of that year, more than twelve thousand mobile phones between the two of them would have been sold. Aimed initially at Britain's 'business executives, sales representatives, journalists, doctors and veterinary surgeons,' it would still be some years before the majority of Morecambe & Wise's old audience would wander very far into this particular consumer market.

As for Ernie Wise himself, he was given one of the phones as part of his payment for plugging the company, but, seeing as he admitted that five years after getting a video recorder he was only now 'just beginning to get the hang of it,' it would not be something that he would ever use on a regular basis. He and his wife, Doreen, would keep it on a shelf in their living room, between a rubber plant and a photo of their dog.

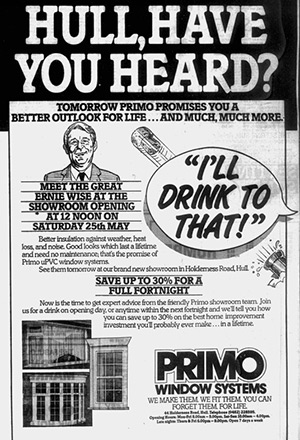

In an odd little echo of Reg Varney's 'progression' from plugging cash dispensers to window curtains, Ernie also moved on from mobile phones to promoting windows - not of the Microsoft variety, but rather the kind provided by Primo Window Systems of Hull. Ever the trouper, he cut the ribbon to open the company's new showroom in Holderness Road; marched down Welby Street in Grantham, followed by a brass band, to further publicise the brand; and also hosted a 'Primo Windows Family Fun Day' at the Pyewipe estate in Grimsby.

Ernie's next 'proper' projects were back within his old familiar show business bubble, appearing on daytime TV as Derek Batey's guest on the chat show Look Who's Talking, then touring a nostalgic one-man show in Australia for a couple of months, before returning to London's West End, and back into something reminiscent of his Vodafone Victorian outfit, to star in the musical adaptation of Charles Dickens' The Mystery of Edwin Drood. He would, nonetheless, remain rather proud of the fact that he had played his own little role in another medium's history.

There would be several other comedians who would follow in his and Reg Varney's celebrity footsteps as far as touting new technology is concerned. Rik Mayall, for example, was persuaded to popularise Nintendo, Stephen Fry urged people to try cloud computing and John Cleese - a serial recommender - introduced such new-fangled products as Magnavox portable compact disc players, Sony Trinitron TVs, DirecTV streaming services, Compaq computers and Intel mobile processors. There are even several agencies around these days that offer a roster of 'comedy influencers' to help promote any new gadget that's about to come out.

It thus seems that comedians, for the foreseeable future, will remain high on the wish list for unveiling innovations to the masses - who knows, perhaps Lee Mack will one day be launching the first consumer jet pack, Michael McIntyre inaugurating the age of low-budget neuromorphic computing, or Alan Carr presiding over the formal switch to zero emission vehicles, or Katherine Ryan fronting all three along with just about everything else. Their presence might not always make much sense, but, bearing in mind the promethean powers that every new package is likely to unleash, we may as well begin each uncertain journey with a smile instead of a frown.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more