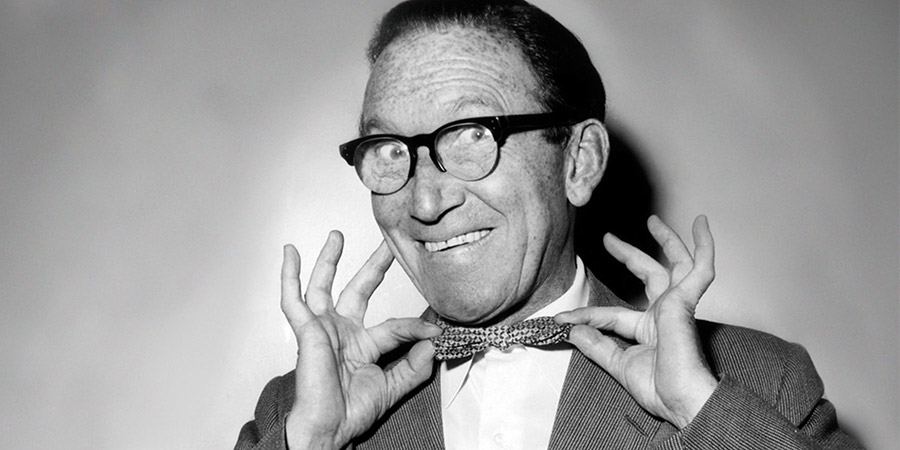

But while there's moonlight... The magic of Ernest Maxin

Eddie Braben used to have a name for Ernest Maxin: 'Ernest Maximum'. It was an excellent appellation, because, of all Britain's TV comedy producers, he was the one whose programmes could always be relied on to arrive with all of the available bells and whistles.

He simply loved a spectacle. If he could have worked in any other time and place, it would have been during the golden age of Hollywood, crafting all-singing, all-dancing, musical-comedy extravaganzas for RKO or MGM. As it was, he worked in the golden age of British television, shaping shows for the BBC, but he still contrived to bring some of the old big screen glitz and glamour to the contemporary small screen grind.

He had an extraordinary career. In fact, he had a couple of extraordinary careers. The first one, however, was over before he had even reached his teens.

Born Ernest Cohen on 22nd August 1923 in Plaistow, East London, into a musical family (his Polish father had been a violinist) that now earned its income from the tailoring trade, he was a precociously gifted pianist, competent in several classical pieces by the age of six. A friend of the family, Harry S. Pepper (an impresario responsible at the time for a BBC radio show called The Kentucky Minstrels, featuring a black-face minstrel band), heard him playing some Bach and Mozart in the family's front parlour, and immediately said to his parents: 'You know, we'll take the kid on tour with us. We'll black him up and we'll make him a minstrel'. His father protested, 'No, mein boy is going to be a classical pianist,' but his mother said, 'How much, love?'

Accompanied by a governess, Maxin (the family name had recently been changed) spent the next three years travelling the major theatres in the country, not only playing piano for the band but also receiving training in everything from tap-dancing to cross-talk timing from the other performers in the company. The combination of his musical skills and his 'cute' appearance made him a popular figure with audiences, and he became thoroughly enchanted by the show business world.

It then all came to an end alarmingly abruptly, late one summer afternoon in 1932, shortly after a matinee at the Sheffield Empire. Heading towards the exit to take a breath of fresh air, he overheard Pepper speaking to Mr and Mrs Maxin on the telephone: 'Dora and Max, I'm sorry to tell you, but I think the kid's washed up in the business'. He was just nine years old.

Handing him two weeks' notice, Pepper explained that he had literally outgrown his role in the show. 'The problem was,' Maxin would later tell me, 'I'd had a growth spurt and now looked about three years older than I was. I was a big beefy kid and looked very mature. So whereas before I'd looked cute when my feet wouldn't touch the pedals on the piano, you see, I'd now lost that sort of child-like charm for the audiences.'

He would come to understand this verdict in the years that followed, but at the time he was simply shell-shocked. 'I just thought, "Oh God, I'm finished!" I was the only guy who was washed-up at nine without a pension!'

He returned to school in London, and, having spent so long living and working with adults, for a while he enjoyed just being a child again. Eventually, however, the bug bit back, and he started missing the adrenaline rush that came from appearing in front of an audience.

Leaving school at sixteen, he found work as a musician, dancer, choreographer and actor, appearing, amongst other places, at London's Hippodrome and then the Windmill Theatre in Piccadilly before being called up by the RAF in 1944. Five years later, he was in Melbourne, Australia, sharing the stage with Arthur Askey in the musical-comedy The Love Racket (during which time, with typical energy, inquisitiveness and enthusiasm, he taught himself how to cut hair and became the company's barber, got invited to perform solo musical spots at exclusive society events, delivered a talk to the country's broadcasting industry and also wrote a new theme song for the production).

Back in Britain in 1951, he recognised that television was now the medium with the momentum, so he started seeking work in it as a choreographer and performer. Quickly curious about the mechanics of programme-making, and ever-ambitious, he sought out Ronnie Waldman, the BBC's first Head of Light Entertainment, and told him that he was keen to become a producer.

Waldman advised him that he would have to start at a lower level, and arranged for him to shadow a number of experienced programme-makers, including Bill Lyon-Shaw, Richard Afton and Rudolph Cartier, and eventually he graduated to overseeing his own shows. One of the first, rather ironically, was Running Wild, Morecambe and Wise's television debut in 1954, which proved so unpopular (mainly because of the standard of the scripts) that the double act would not get another chance on the small screen until the start of the next decade.

It did not take long, however, for Maxin to find his feet in the medium, and he went on to work during the next few years with a remarkable range of comic figures from that era, including Frankie Howerd, Benny Hill, Peter Sellers, Ted Ray, Terry-Thomas, Eric Sykes, Des O'Connor, Max Bygraves, Bob Monkhouse, Dave King, Norman Wisdom, Jimmy Jewel and Ben Warriss, Spike Milligan and even, on a rare visit to Britain in 1956, Jack Benny. Thanks to his unusual upbringing, he was able, unlike most of his colleagues, to speak to each artist as a fellow performer as well as a producer, not only explaining but also demonstrating how he wanted things to be done.

Indeed, so strongly was the show business spirit imbued in him that he was never going to become a conventional kind of producer/director. There was always a feeling that Maxin was 'up to something' - not in any devious, Dennis Main Wilson sort of way, but simply in the sense that his interests could never be confined to one fixed category.

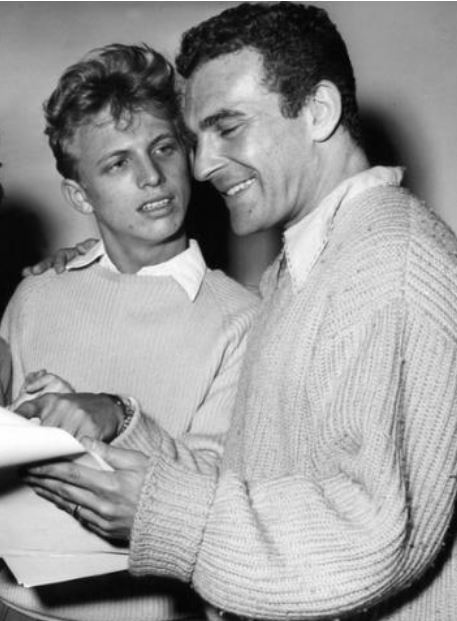

He continued, for example, to write songs, play music, contribute choreography and dance whenever he had the chance (and with his good looks and stylish demeanour he could, had he been so inclined, probably have given Lionel Blair a run for his money as television variety's top twinkle-toed supporting player). He was, in addition, always nurturing some new talent or other, taking huge pride and delight in seeing them go on to successful careers (he taught Tommy Steele how to dance, coached innumerable young performers in musical technique, and worked hard - usually unpaid and uncredited - devising eye-catching routines to help them get noticed). He also loved indulging in the odd bit of playful mischief, such as when in 1959 he had his own orchestra record a Christmas album of mood music called F#, Where There is Music - each cardboard sleeve of which, as the album was sponsored by Fabergé, was sprayed with the cosmetic company's brand new 'F Sharp' fragrance before being sent out to customers.

Increasingly, however, his greatest passion was for programme-making, and the 1960s saw Maxin establish himself as one of the best and most versatile producer/directors in British television. He was responsible for the Norman Hudis sitcom Our House (1960-62), which featured the likes of Hattie Jacques, Charles Hawtrey, Joan Sims and Hylda Baker; he was an assured and enthusiastic manager of such variety shows as Make A Date (1960) and David Nixon's Comedy Bandbox (1966); he was a safe pair of hands for sketch and stand-up comedians, as he demonstrated with The Dick Emery Show (1966-70) and The Dave Allen Show (1969); he oversaw several musical-comedy vehicles such as The Kathy Kirby Show (1964-66); and he was also more than happy to take on such quirky one-off projects as Ice Cabaret (1968).

He attracted most praise during this period for his work with Charlie Drake, which started in the late 1950s and lasted, on and off, for a decade. The most famous routine on which they collaborated featured a full orchestra performing Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, with Drake - thanks to Maxin's clever editing and camera tricks - playing all of the instruments and conducting the whole thing as well.

It was a classic Maxin moment, combining his love of music, comedy and spectacle to produce the kind of television event that got people talking for days after it was screened. When it was included as the highlight of a compilation package, The World Of Charlie Drake, it won Maxin and Drake the prestigious Charlie Chaplin Award for the funniest show at the 1968 Montreux Festival, and cemented the producer's reputation as television's go-to man for glossy invention and glamour ('They started calling me "Mr MGM" - "Maxin Goldberg Maxin"!').

One person who went to him precisely for this special quality was his friend and fellow producer/director John Ammonds. In 1971, the man in charge of The Morecambe & Wise Show was looking to take the programme up to the next level by bringing in more star guests, but not simply to give them 'straight' solo spots but rather involving them in comic routines with Eric and Ernie. Maxin, Ammonds knew, was the ideal person to help him, his writer and his stars devise some imaginative and unlikely routines for these eminent figures, and Maxin (whose own office in Television Centre was a mere two doors down the corridor) was only too happy to get involved.

His first contribution was to put together the 'Smoke Gets in Your Eyes' sketch with Shirley Bassey. It was a charmingly clever deconstruction of the usually slick and reverential star appearance: she entered, resplendent in a glittering dress, to much orchestral noise and sparkling studio lights, and then the stage revolved to reveal Eric and Ernie, in workman outfits, cranking the mechanism around; there then followed the sight of a bottle of champagne sliding away on a slanting table, and then, after the heel of one of her sling-backs gets stuck in a block of polystyrene, finishing the song with a foot shuffling away in a heavy-looking hobnail boot.

The basic aim had been the gentle humbling of the hyped-up celebrity, the dragging down to earth of the star, and it did that perfectly, but Maxin turned it into something more than that, so structurally elegant, so wittily intelligent in its progress, that it was something to savour in its own right. It was exactly what Ammonds and Morecambe and Wise had wanted: style, subversion and silliness.

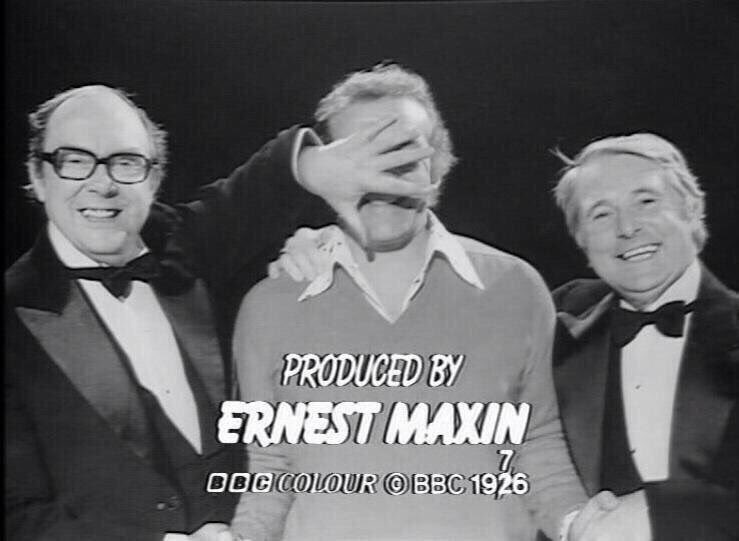

It was this and subsequent inspired visual routines that made Ernest Maxin part of the programme's special quintet - Ammonds, the writer Eddie Braben and Eric and Ernie, along with Ernest himself - responsible for the purest and most satisfying period of The Morecambe & Wise Show. Each one of these tremendously talented and industrious and humble professionals contributed the best that they had to make the programme arguably the most beautifully pitched and consistently entertaining comedy show of the era.

The dynamics would change somewhat in 1974, when John Ammonds left (partly because he needed to spend more time caring for his wife, who had MS, and partly because he felt the show needed freshening up) and Maxin took over as producer. The change would not affect the show's success - indeed, in terms of ratings, it would go from strength to strength - but it would see a shift in the show's complexion.

For one thing, there was a subtle change in the distribution of power within the double act itself. Ammonds had been closest to Eric: they were both very down-to-earth Englishmen, they were both addicted to comedy and they both had an obsession with getting the scripts exactly right. Maxin was closest to Ernie: both of them had been child stars and still thought of themselves primarily as song and dance men, both of them had grown up bewitched by the romance of classic Hollywood, and both of them adored the idea of staging glamorous and elaborate musical-comedy routines.

When Ammonds was in charge, therefore, Eric's vision for the show remained dominant. When Maxin took over, Ernie's vision, while not eclipsing Eric's, certainly became much more influential.

The shower-free 'Singin' in the Rain' routine would be particularly symbolic of this shift in emphasis. Eric had his key comic role to play, of course, which he executed with his usual perfect judgement, but the loving care invested into recreating the classic movie moment, and the joyous sight of Ernie going back to his roots, and his dreams, losing himself, like Maxin would have lost himself, in that silver screen scene, was a real 'Ernest and Ernie' labour of love. Eddie Braben's running joke had been that Ernie was always yearning to go to Hollywood; now Ernest Maxin was bringing a bit of Hollywood to Ernie, and to the show.

The Maxin era thus came to be best known for the show-stopping extravaganzas. As he once explained to me, it was a very deliberate move:

You have to have a talking point in a show. That's important. Something visual - people don't remember dialogue, they remember images. [...] Of course, any great show needs a variety of things - the front cloth routine, some sketches, some music - you need to use warmth, subtlety, you need changes of pace, but you also need something in the show that has everybody saying to each other the following day: 'Did you see that?'

He was wrong about people not remembering dialogue - e.g.: 'Why, that's very nearly an armful!'; 'Don't tell him, Pike!'; 'Don't mention the war!'; and, much closer to home, 'He's not going to sell much ice-cream going at that speed, is he!' - and the either/or way of thinking about the issue was telling (not least for Eddie Braben), but there was no doubting the brio with which he pursued this belief. What he did, and how he did it, was often triumphantly inspired.

Only Ernest Maxin would have thought of getting the newsreader Angela Rippon to dance with Eric and Ernie while they sang A, You're Adorable and also ensured that it worked so extraordinarily well. Only he would have thought of adding a version of How Could You Believe Me from Fred Astaire's movie Royal Wedding into a sketch featuring Diana Rigg as Nell Gwynne, or dreamed up a brilliant Slaughter on 10th Avenue pastiche with Ernie in the woman's role, or created a lavish song and dance routine for Penelope Keith that is thwarted by an unfinished staircase, or came up with the idea of recruiting an eclectic assortment of middle-aged BBC presenters and, through camera trickery and clever editing, have them 'perform' in a dazzlingly acrobatic South Pacific homage that, of course, he had choreographed himself.

One of his most memorable routines, for its focus purely on Eric and Ernie themselves, was the 'making breakfast' cooking and dancing routine that he developed for their 1976 Christmas show. Based on a simple idea that Ernie had scribbled into a notebook back in the early 1960s, it had never been developed into something that seemed substantial enough to record until Maxin brought his special skills to realising its full potential.

He pondered the possibilities all through most of one day without quite picturing anything that excited him, until, late into the evening, his wife asked him what he wanted for breakfast the following morning: 'Do you want toast? Grapefruit? Coffee?' It was the list that clicked for him:

Suddenly, I could visualise the whole routine in my mind. The toast popping up: boing! The grapefruit being cut: Bam! Bam! Bam! Everything. I said, 'That's it! That's it!' And I stayed up through the night in our kitchen, writing the top line of music down and where all the gags came in - like the toast would come up on the third beat of the fourth bar, or whatever it was, you know. Then I put in the musical punches - like when the toast comes up the music would go du-dum-phweep-doing, you know, as they caught it. Chopping the grapefruit: pum-bah-pum-bah-pum-bah. Squeezing it: diddley-diddley-diddley. And in the middle phrase, where Ernie's catching and smashing the eggs, you get Rom-ching-crash-bang! Rom-ching-crash-bang! from the orchestra. Mixing the omelette: Brrrruuuuummmm-da-da-da-dum. I had to write the top line in, all the little musical accentuations to synchronise with each visual gag.

Then I put in things like the one pancake going up and then four coming down, you know, all of those things. This went on and on. The next morning, my wife came down and saw me - and the mess all over the kitchen! - and thought I'd gone completely mad! But I'd got it. I'd got it down. I went to work that morning, explained the routine to them, and they said, 'Okay'. We worked on it some more, and, of course, they used their skills to make it even funnier, and it was there. We shot it in just fifteen minutes - the whole thing. And we'd got our talking point.

Maxin's last project with Morecambe and Wise, their 1977 Christmas special, was watched by an estimated 28 million viewers - almost half the nation - and it was a testimony to his programme-making philosophy, as well as to the stars' brilliance. It won them a BAFTA, and a huge amount of critical praise.

Morecambe and Wise moved off to Thames TV soon after, and asked him to join them there, but Maxin stayed loyal to the BBC. 'I told them, "No, I don't think so,"' he later recalled for me. 'I said that the atmosphere [at the BBC] was so good, and the shows were going so well, a change didn't seem wise. So, you know, I wished them luck, and I prayed that they would do okay, but we'd reached such heights at the BBC - because of that special teamwork between us - and where else were you going to get 28 million viewers?'

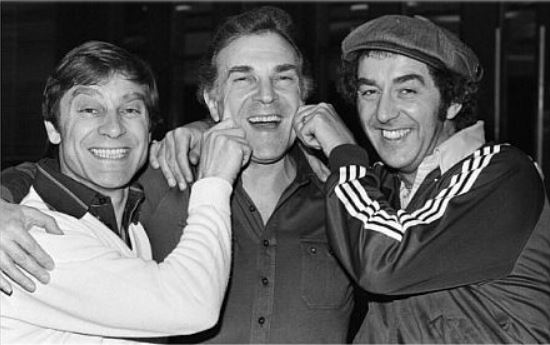

He continued to make successful shows with a wide range of talents. He worked with Kenneth Williams on International Cabaret (1978), Lennie Bennett and Jerry Stevens (pictured) on three series of Lennie & Jerry (1978-80) and also produced two series of The Les Dawson Show (1982-83). Each project reached the screen stamped with the distinctive Maxin signature: polished but populist, with some aspect or other that was primed as a talking point for the following morning.

It didn't matter if the performers protested that there was only one dimension to their act - Maxin would simply add the other ones himself. No one worked with him and failed to emerge with an improved, or entirely new, skill or two. As the comedian Lennie Bennett would reflect, 'When I met him I told him straight that I had three left feet and I was tone deaf, so it was no use trying to get me to do anything else except tell gags. Within weeks he had me singing and dancing and even rehearsed us for five days a week for three weeks to do a trapeze act.'

He also continued to search for new potential stars - when, for example, Bradley Walsh had not long moved on from being a Pontin's bluecoat, Maxin was already predicting enthusiastically, and with what turned out to be remarkable accuracy, that he would become, if encouraged, an all-round prime time entertainer - and he never stopped pursuing new ideas.

He remained the kind of figure whom many people probably thought didn't exist outside of old feel-good 'let's do the show right here' musicals. He never stopped daring to dream, but, unlike most dreamers, he had the talent and the nous to make quite a few of those dreams come true.

Forced to retire from the BBC at sixty, as per the Corporation's then-regulations, he remained remarkably fit and energetic for the best part of another three decades, providing invaluable advice to young performers and programme-makers, contributing to various theatrical and television projects and always making himself available whenever and wherever he thought he could help.

As a person, like most of us, he had his little eccentricities. He was, for example, rather vain about his appearance - he was always a good-looking and very dapperly-dressed man - and went through one phase when it really seemed to matter to him that people thought that he resembled Burt Lancaster. Someone, evidently, had told him once that he looked just like the square-jawed and bright-toothed Hollywood star, and it had pleased him so much that, for a while, he wanted it re-confirmed by whomever he met. When, in my presence, someone responded to his by now all-too familiar question, 'Who do you think I look like? A big American star. Have a guess!' by opining, just (if not more than) as plausibly, 'Er...William Shatner?' he looked crestfallen - '[p=10763]William Shatner]??? No! [p=10763]Burt Lancaster] - everybody says so!!!'

He was also so devoted to old Hollywood musicals, so in love with each and every black-and-white or glorious Technicolour dance routine, that if one happened to be having lunch with him in a very smart and quiet London restaurant, and one happened to make a casual reference to any one of those memorably choreographed sessions (let alone a direct mention, as I once made, of the great Hermes Pan), before you knew it he had tossed his napkin down on the table and was up on the balls of his feet ('It went like this...') and he would be leaping and spinning around, dancing up and down between the tables, playing Gene Kelly, while everyone else in the room, knife and forks frozen in mid-air, stared up in wonder at this remarkable man.

Such character quirks simply made him all the more endearing. One thing, however, that sometimes made him just a little bit exasperating, at least for a researcher, was that he had inherited the old Hollywood habit of 'embellishing' his anecdotes to the point where one would always have to go off and, via a fact-checking process that was almost as frustratingly time-consuming as herding a mass of feral cats, 'reduce' them back to reality. He also, in his later years, tended to furtively re-edit the timeline of his long and distinguished career in order to obscure his current age ('If they see the early credits,' he would tell me with genuine anxiety, 'they can date you, and then they won't use you'), which, while understandable up to a point, rendered many of his important reminiscences riddled with factual errors that would require plenty of tactful corrections.

That, however, was Ernest Maxin. He was a kind-hearted, generous, very emotional man and an incurable romantic, and that, mixed in with his incomparably rich show business experience, his rare creative intelligence, his cool-headed technical precision and his insatiable desire to make millions of people very, very happy, was what made him so special.

The last time I met him, in a shadowy make-shift studio, was very poignant, because it soon became clear that his once-sharp brain was failing, and the memory seemed to be fading. We were both there to be interviewed, once again, about Morecambe and Wise, and I became extremely concerned as to how he was going to cope. Once he sat down in front of the camera, however, his eyes seemed to sparkle, his face was suddenly focussed, his smile was strong and sure, and there was the old Ernest again: a man talking about all of the magic he had helped to make. He did some dance steps on the way out, as immaculate as ever.

He died on 27th September 2018, aged ninety-five, in a nursing home in Woodford Green. For a man who had grown up mesmerised by great Hollywood lives, he must have been thrilled to have reflected, during his final few years, on the fact that, in his own inimitable way, he had actually lived one.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more