The true Lord of Misrule: 'Monsewer' Eddie Gray

We often describe odd, unconventional, subversive comedy things as 'Pythonesque', or, for those who can look back a little longer, 'Milliganesque', but, strictly speaking, we really should be describing these things as 'Grayesque'. It is hardly surprising that we don't - for one thing, it would sound somewhat odd to liken something colourful to something grey, and, for another, hardly anyone would have the slightest clue as to what on earth we meant - but, all the same, it is a bit of pity, because Eddie Gray deserves to have an 'esque' just as much as do Spike Milligan and the Pythons.

Eddie Gray, who died back in 1969, is better known today, to the few who do still know him, as 'Monsewer' Eddie Gray, the music hall comedian and on-off (think Robbie Williams and Take That) member of The Crazy Gang. From the 1920s all the way through to the 1960s, he was arguably the most artful, unpredictable and mischievous comic spirit in the country, described by his contemporaries variously as 'The black swan of comedy', 'The comedian's comedian' and 'The funniest man in the world'.

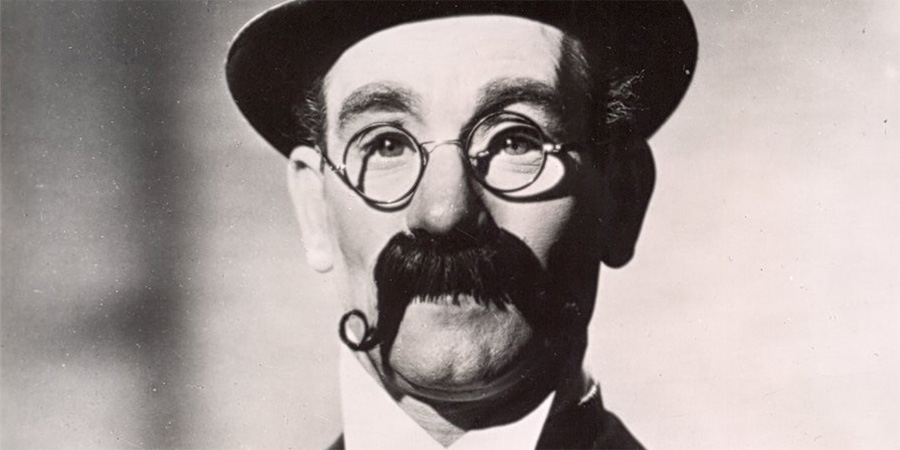

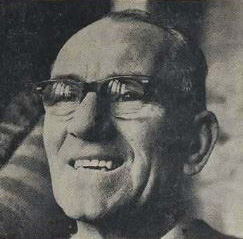

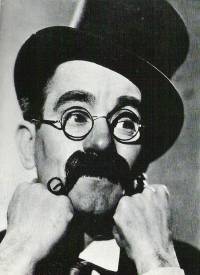

Off the stage, clean-shaven, smartly-dressed and quiet, he resembled a blandly respectable bank manager, or, as the critic James Agate once put it, 'an income tax collector on a busman's holiday'. On the stage, transformed by his battered top hat, wire-framed lens-less spectacles, glued-on looped moustache and cherry-red nose ('How are you, all right? Enjoying yourself? I'll soon put a stop to that!'), he appeared to be a toff looking for trouble, and sounded like a commoner who knew where to find it.

There was more to him, however, than an act. His whole essence was infused with natural, untamed, authentic humour - a way of looking at the world, and wanting to exist in the world, that was driven only by a desire to laugh and smile - which made him and kept him distinct from most other individuals, let alone the fellow performers, in his life.

It did not really matter if Eddie Gray was 'on' or 'off', if he was in or out of his stage persona, if he was in front of an audience or rubbing shoulders with them on the street. Whatever he looked like, and wherever he was, what he would do was always stimulated by an irrepressible impish spirit.

Born Edward Earl Gray in Pimlico in 1898, his early life was fairly typical of precocious young performers in those loosely-regulated days. His father, who ran a greengrocer's stall in the Vauxhall Bridge Road, was happy enough, after watching him teach himself to toss and catch an assortment of apples, plums and pears (and then eat them as each one dropped), to arrange for him to be apprenticed to a juggling troupe at the tender age of nine.

He started learning his trade by performing in pubs and clubs in and around Brixton, where Charlie Chaplin was one of his contemporaries (and where his friend and future stooge, Jack Hartman, was developing a stilt-walking act with the assistance of a young man named Archie Leach - the future Cary Grant), before travelling with the troupe all over the country. Initially a 'straight' juggler, his naturally humorous disposition saw him gradually evolve as a performer into a more comic figure, combining impressive technical dexterity with a disarmingly whimsical sense of fun.

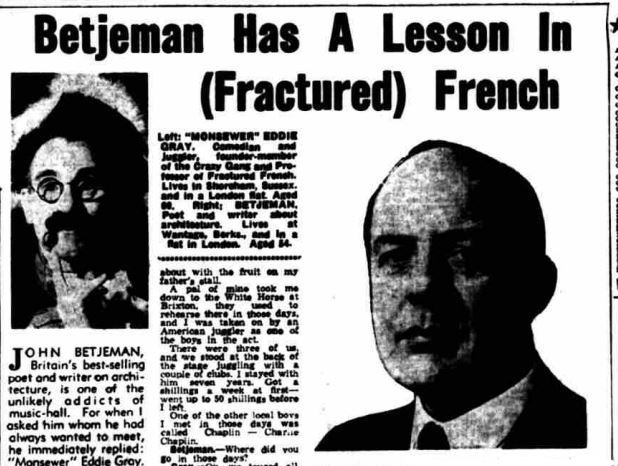

It was during a period abroad, working in Paris night clubs, that he stumbled on to another aspect of his act. Unable to speak more than bits and pieces of French, but needing to communicate his cues to the stage hands, he started inventing his own version of what would later be termed Franglais: 'Moi's going to get la hoop, an' throw it to one side, and vous' goin' to catch it, oui?'

By the time he was back in Britain, he was speaking it to get laughs: 'Madame and Masseurs...Now, ce soir - that's foreign for this afternoon - moi is gonna travailler la packet of cards - une packet of cards, not deux, une. Now je 'ave 'ere un ordinaire packet de playing cards, cinquante-deux in numero - fifty-two in number - ein, swine, twine, and every card parla la même chose. And I cuttee in deux, with vang-sess ici and vang-seess there-ci...'

If ever he had any hecklers, he shut them up in the same style: 'Voulez vous obliger moi and turn it up, chums? Mercy beaucoup.'

He was also starting to do various magic tricks that were designed to go wrong, as well as comic patter and interactions with stooges planted in the audience, often while still juggling an increasingly wide and peculiar range of objects. A childhood friend of his, Jimmy Nervo, had formed a double act with fellow comic Teddy Knox, and he sometimes worked with them for certain routines and shows.

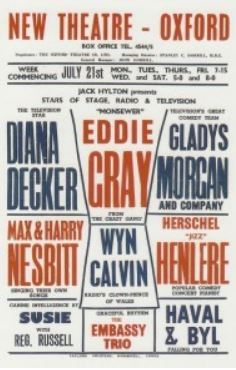

By the mid-1920s, Gray was considered talented enough to tour Australia and South Africa as part of Sir Harry Lauder's hugely successful variety company, and then, after resuming his solo career back in Britain, he was reunited with Nervo and Knox, along with another double act, Naughton and Gold, for a revue called Crazy Week at the London Palladium in 1931.

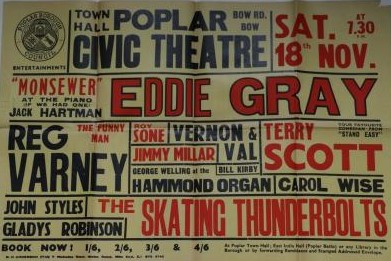

Described by one critic as 'the maddest, the most riotous, the noisiest week ever known in a London music-hall,' the show would prove so popular that it would spawn several more Crazy Weeks and even Crazy Months, and, once Flanagan and Allen were added in 1932, the group started to be called the Crazy Gang (and Gray was given the stage moniker of 'Monsewer' by the impresario Val Parnell because of the growing popularity of his cod-French routines).

A huge and enduring comic phenomenon in Britain, the Crazy Gang would go on to enjoy three decades of success interrupted only by the Second World War. Gray himself, however, was the single performer surrounded by pairs, and remained, by default as well as disposition, something of an outlier within the group.

One of the roles that he devised, in addition to his own individual act, was that of the authority figure who interrupted group routines with mock-indignation. It would, of course, later be adopted by Graham Chapman, as the humourless colonel who kept trying to curtail Monty Python sketches ('Stop that - it's silly!'), but Gray would play a number of characters who would suddenly spring up from a theatre box, or stride on from the wings, and express their anger at what was happening, often then being rudely disabused of their impression and having to retreat in embarrassment and shame.

One Crazy Gang routine, for example, saw the others take part in a Greek dancing exercise, which was suddenly halted by Gray leaping up angrily from a seat in the balcony and shouting: 'I happen to be the Norwegian Ambassador, and you have just insulted my country!' When one of the group then protested, 'But this is Greek,' Gray simply said, 'Oh,' and sat down again as the dancing resumed.

Continuing with his solo act in between Crazy Gang productions (being the lowest-paid member of the troupe would only heighten his sense of independence), he put on shows that were fresher, smarter and far more surreal than anything else seen on the British stage at that time. His routines would include plenty of juggling with all kinds of improbable props (and sometimes featured him getting on to his knees and shuffling across the stage - 'This is the trick I usually do on the wireless'- or just ambling off, absent-mindedly, to leave everything in orbit to come crashing down to earth); several magic tricks that would go horribly wrong; a mind-reading act that always ended in chaos; some trained doves secreted in various places around the auditorium; plenty of interaction with the audience; and a performing dog that wouldn't perform (he would hold a smallish-looking hoop high up in the air and encourage the dog to leap through it - 'Right through the centre, don't touch the sides - understand? You've got nothing to worry about!' - but the dog, after glancing up at it, would simply wander off and lie down).

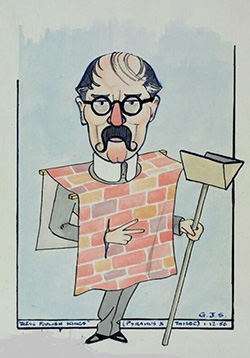

He would concentrate on his individual career both during the war (when he travelled thousands of miles entertaining the troops) and immediately after (when he sometimes toured with the up-and-coming comic Arthur English, a grateful student who always said that Gray 'didn't have a selfish bone in his body'), but re-joined the Crazy Gang in 1952 and remained a member until they gave their last performance in 1962 after entertaining, all in all, an estimated 20,000,000 theatregoers. He then enjoyed a further wave of success by playing Senex, the lecherous but henpecked old senator, alongside Frankie Howerd in the first London production of Burt Shevelove, Larry Gelbart and Stephen Sondheim's A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum.

He would never retire, touring on with the musical and then making all kinds of guest appearances along with his solo spots right up to a few days before he died, aged seventy-one, at the end of the decade. Paul Jennings, writing beautifully about him in The Times after his passing, celebrated the authentic unruliness of his comedy, speculating that, rather than using an art to conceal his art, Gray was simply one of those rare souls who have the gift of giving in to 'their true, magnificent, quirky, natural selves, unburdened by any preconceived theory'.

Jennings also called him 'a total character', and, although that phrase has since come to serve as a careless platitude, Jennings used it very precisely, and pertinently, in relation to Eddie Gray. He meant that the man was completely, and coherently, and consistently comical. There was never any neat and simple distinction between Gray the performer and Gray the person. He was a funny man, full stop.

One of the consequences of this was the fact that, as less free and fluid thinkers would put it, he was always 'up to something'. He was like a reverse proof-reader, adding the errors back into life's text. Where there was order, Gray brought disorder, and where there was a smug sense of control, he created a humbling sense of chaos.

Most of the time it was simply instinctive, but sometimes it was deliberate. It is understandable that the deliberate things were often categorised as 'practical jokes' and 'pranks', but, as distinctive and memorable as so many of them were, they were all of a piece with the tenor of his temperament.

Probably the best-known of his on-stage 'pranks' was one of his last. It was the summer of 1967 and he was appearing in a show at Brighton's Palace Pier. The star was the lantern-jawed London comic Tommy Trinder, who was himself on the way down the show business ladder but was still rated as quite a big name around the provinces. Gray, having been left less-than-impressed by Trinder's arrogant attitude to some of the other members of the cast, decided to teach him a lesson.

One day, Gray said to him, 'You know, I think I've got a great new idea for my act, and it would be marvellous, if a big star like you would come on and do the gag with me'. 'Course I will,' Trinder replied. 'What do you want me to do?'

'Just walk on for a start,' said Gray at his most flattering. 'I'll be juggling. The audience will be thrilled to see you. Then all you have to do is to say, "Hello, Eddie, you're looking lively - what did you have for breakfast today?" I'll say "Haddock". You say "Finnan?" And I'll say "No, thick 'un". I know it doesn't sound much, but I know it'll get a big laugh if it's you doing it with me.'

Trinder, understandably, didn't think the gag was up to much, but, just to humour the older comic, he agreed to take part. 'Shall I do it tonight?' he asked. 'Oh no,' answered Gray earnestly. 'I'll need to get it into my head first. If we run through it every day I can put it in at the weekend.'

Thinking that his old friend was really getting past it, Trinder, out of pity, thus duly endured the repeated rehearsal of the 'joke' throughout the rest of that week:

TRINDER: Hello, Eddie, you're looking lively - what did you have for breakfast today?

GRAY: Haddock.

TRINDER: Finnan?

GRAY: No, thick 'un.

Then it came to Saturday night. 'We've got a full house tonight, Tom, so I'd like to give the gag its best chance,' Gray said excitedly. 'Can we do it tonight?' Trinder, who by now was thoroughly bored with the whole thing and just eager to get it over with, replied: 'Sure'.

Later on during the show, therefore, Trinder stood in the wings while Gray did his juggling act as usual in front of the audience, waiting patiently for his special whispered cue. After a couple of minutes, it came: 'Now'.

Trinder strolled on to the stage, beaming his toothy grin, as he received a big round of applause. Then he went straight into the gag:

TRINDER: Hello, Eddie, you're looking lively - what did you have for breakfast today?

GRAY: Cornflakes.

Gray then continued with his juggling, seemingly oblivious of his fellow comic's presence, leaving Trinder, who was normally one of the most quick-witted ad-libbers in the business, motionless and mute with confusion.

He found another novel put-down when he was a spectator at a London boxing match. It was turning out to be a particularly slow, dreary, body-hugging ten-rounder, and eventually Gray, finding it all too much to take, solemnly arose from his seat, walked slowly towards the stage and, once he sensed that he had the crowd's full attention, threw a bunch of keys into the centre of the ring. Both boxers stopped and stared at him uncertainly. 'I'm going now,' Gray shouted at them. 'Lock up when you're finished.'

One of his most-repeated and eventually most notorious of practical jokes, 'out in the open' so to speak, concerned pillar boxes. Gray could rarely resist pillar boxes.

His main routine always went more or less as follows. If he thought the street was busy enough, he would walk over to the nearest pillar box, move close as if ready to slip in a letter, freeze for a moment, put his ear to the slot, recoil in mock-shock and exclaim loudly: 'Well, how did you get in there???'

One or two other pedestrians would now start to stop and notice this strange sight. Gray, seemingly oblivious to them, remained focused on the pillar box, his ear stuck over the slot as he continued his one-sided conversation. 'You what?' he would gasp.

He would then glance around anxiously at no one in particular, shaking his head while crying out, 'I don't believe this!'

A small but very curious crowd would be gathering around him by now. 'There's a postman in there!' Gray, with a wide-eyed look of astonishment, explained to them. 'He fell inside as he was collecting the letters and the door closed behind him!'

He would then quickly stick his ear back over the slot, appear to listen, nod, and then shout down into the hole, 'Yes - I'm telling them!'

He would look at the others: 'The poor bloke's starving - has anybody got any food?' If someone volunteered a bun or a sandwich, he would post it through the slot and shout: 'That'll keep you going!'

After another listen and a nod, he would shout, 'It's all right, don't panic. Look, I'll nip round to the post office and get a key. Just hang on!'

He would then turn to what was now a large assemblage of deeply concerned onlookers and say, 'Look, you lot keep him talking while I go off and sort this out!'

He would then stride off very purposefully down the street, leaving a succession of anxious people to take turns shouting into the slot. 'Oh my gawd,' one of them would gasp. 'I think he's fainted - he's not answering!'

On another occasion, he was on his way to the Victoria Palace when he spotted some workmen about to cement another pillar box into place on Westminster Bridge Road. Hurrying over, he pulled out his Variety Artistes' Federation membership card and flashed it at them in authoritative fashion, announcing himself as 'Mr Shankers, Post Office Pillar Box Siting Officer'.

Now that he had their full attention, he proceeded to pick up and peruse their page of plans, blink a couple of times, suck his teeth for a moment and then declare: 'Yes, yes, this is correct - but it has to be the other way round'. The workmen would look at him with a slightly puzzled expression.

'You see,' he would go on to explain rapidly, 'it's very difficult for the scrimson scrayville to undulate the cordwinder unless it's facing the other way. Do you see?' They nodded meekly back at him. 'Right then,' he went on, 'we'll check once we've instigated the traffic-fill at the junction box.'

He then marched past them and continued on his way. The workmen duly repositioned the pillar box so that it now faced on to the road.

Gray also delighted in using his friends and colleagues as his unwitting stooges. Once, for example, he and a number of other performers went to entertain the inmates at a prison. It all went very smoothly until, as they were making their way back out of the institution, Gray sidled up to a duty guard and, with a worried expression, directed his eyes at the performer behind him and mumbled out of the corner of his mouth: 'He wasn't with us when we came in...' As Gray thus continued towards the exit, he could hear chaos breaking out in the background as his hapless victim was left to protest his innocence.

Arthur English, when they worked together in the Fifties, became the butt of countless jokes. One of them concerned their lodgings during a tour. Advising the younger man to do what he always did when he reached Birmingham, he told him to book a room at a boarding-house run by a certain Mrs Coombs in Hagley Road. 'She's a charming lady,' Gray explained, 'but she's absolutely stone deaf, so you'll have to shout.'

When English arrived at the premises, therefore, he felt well-prepared as he knocked on the door:

ENGLISH: MRS COOMBS?

COOMBS: YES?

ENGLISH: MY NAME IS Arthur English.

COOMBS: HOW DO YOU DO?

ENGLISH: FINE. AND YOURSELF?

COOMBS: I'M NOT DEAF, YOU KNOW!

ENGLISH: NEITHER AM...eh??

On another occasion, an old friend decided to visit Gray in his dressing room between the afternoon and evening performances. 'Wonderful to see you,' said Gray, wiping the make-up off his face, 'but look, I've only got twelve minutes, got to change from finale costume to opening, get a bite to eat, write a couple of letters...' Apologising for the interruption, the friend backed off, wishing him well and promising to send him a card or something soon. 'Tell you what,' said Gray brightly as the friend was heading back out the door. 'Why don't you come and see me between the shows?'

One prank that he performed several times in the months that followed the Great Train Robbery in 1963 saw him and a colleague enter some well-appointed West End restaurant with a heavy-looking postal sack slung over his shoulder. It was actually stuffed full of blank paper notes along with a few bona fide fivers.

He would sit down, put the sack under the table and order a meal, and eat it whilst behaving in such an agitated way that he eventually had everyone else in the room monitoring him closely, then he would produce a thick wad of notes, pay the bill, and start heading off. He would then stop, mutter that he hadn't left a tip, go back, reach in the sack, produce another fiver, then contrive to drop the bag so that several more fivers fell out - at which point he would shout, 'Shit, we've been rumbled - run for it!'

Very late on his career, when he was appearing in the provincial run of A Funny Thing..., he took it upon himself to 'look after' his old Crazy Gang colleague Charlie Naughton, who was over eighty by that time and had a minor role in the play. They stayed at one point in the tour above a pub opposite the theatre, and every time they had to cross the road to work they would stop the traffic by walking so painfully slowly and unsurely in front of all the scowling and honking motorists that a line of stationary cars stretched all the way round the next street and the pedestrians had formed into an audience. Once they reached the middle, however, they would suddenly leap into the air and dance the rest of the way to the pavement, causing near-riots as the furious drivers screamed out of their car windows and shook their fists at the departing comics.

Roy Hudd, who was also on that tour, would recall the time when his agent came to visit. Gray, upon hearing the news, suggested that the agent take him and Naughton, along with his client, out to tea for a treat. Hudd was nervous, having witnessed at first hand Gray's daily pranks and eccentricities, but on this occasion, apart from indulging absent-mindedly in his habit of juggling knives, forks and spoons over his head, the old man seemed to be acting almost 'normal'. 'I thought he was behaving well,' Hudd would say, 'until I noticed that, as he was chatting, he was also buttering Charlie's bald head.'

One of Hudd's regular off-stage chores on the tour was to collect Gray from nearby betting shops. 'Those short journeys will stay with me forever,' he would say. 'He was always looking for trouble.'

One day, on their way back to the theatre, he steered Hudd into a branch of Burtons, the men's tailors. Once inside, he carefully examined a number of bowler hats and eventually chose one for his bemused colleague to try on.

A young assistant came up and, recognising Hudd from television, asked him for an autograph. Hudd happily consented, and, after explaining who his distinguished-looking older friend was, the assistant asked him to sign one, too.

Gray then took an overcoat from the rack and put it on. 'What do you think?' he asked the assistant. 'Very nice,' said the young man. 'Good,' said Gray, who then turned and ushered Hudd, still with a bowler hat on his head, straight out of the shop.

The alarmed assistant followed them, saying politely but anxiously, 'Er, gentlemen, you haven't paid yet for the hat and coat!'

Upon hearing this, Gray spun around and exclaimed indignantly, 'Young man, you've got a lot to learn! You had two autographs. His' - pointing at the embarrassed Hudd - 'and mine. Now, he's only just started, so he gets a hat. Well, I've been in the business for many, many years, so I always get a coat. Understand? Now be off with you!' He then turned his back once again and, dragging Hudd by the arm, marched off towards the theatre, leaving the utterly perplexed assistant to splutter his objections at them as they disappeared down the street.

It was ordinary members of the public, however, who would always remain Eddie Gray's favourite targets. Unrecognisable without his stage make-up, and effortlessly dead-pan, he had an extraordinary ability to appear anonymous but important in their presence. One of his favourite tricks, in this sense, would see him pose as a borough surveyor.

He would stop a suitably trusting-looking passer-by, explain his very significant but barely comprehensible job and then ask him or her to hold the tip of a tape measure very tightly against a nearby wall while he went round the corner to calculate, supposedly, the distance between one part of the building and another.

Once he was round the corner, however, he would stop another unsuspecting member of the public and make the same request. Then, after informing both of them, quite separately, that he needed to fetch his 'sextant for the hieroglyphics', he would slip away across the road to a nearby café, order a pot of tea, and sit down by the window, watching to see how long both of his victims would stay in position. Sometimes, much to his delight, it would be for the best part of half an hour.

The older and more vulnerable-looking he got, the less likely he thought it was that he would end up being punched, so the frequency of the pranks grew rather than shrank. Time-wasting mixed with a nagging sense of mystery was a favourite combination.

A bag of turnips became the basis of one such trick. He had a friend who, like his father, owned a fruit and veg shop. He would go in, buy a bag full of turnips, and then stand outside and wait for a suitable victim. When he found one, he would rush up to them and say, 'Would you be kind enough to hold my bag for a minute? I just need to pop in there and buy some turnips.'

The passer-by would agree, and Gray would then go into the shop and slip straight out the back. Eventually, the passer-by, having become restless, would venture into the shop, look around for Gray and, finding no trace of him, stand there looking puzzled.

'Did you see a man come in here wanting to buy some turnips?' they'd ask. Gray's friend would shake his head. 'Only, he asked me to hold on to this bag for him,' the passer-by would explain. So the shopkeeper, feigning curiosity, would ask what was in the bag. The passer-by would then look inside, look back up and, incredulously, would answer: '...Turnips'.

One quick trick that he would frequently try, just to cheer himself up when he was driving long journeys, took place whenever he was motoring through a sleepy-looking village. Once he reached the high street, he would slow up, wind down his window and inquire urgently of whomever happened to be standing there on the pavement: 'Straight on?' They would invariably furrow their brow and look rather puzzled, but then, eager to please a stranger, would nod and start pointing: 'Y-yes, that's right, straight on!'

Another incident occurred in 1960 when he was in the company of the future knight and Poet Laureate John Betjeman. The eminent writer and broadcaster happened to be one of Gray's biggest fans, and, after discovering this, a newspaper arranged for them to have lunch together in a restaurant just off Leicester Square in London.

Once they had eaten and drunk and chatted away for a couple of hours, they left together and ambled up the road towards Charing Cross. Coming the other way, rather forcefully, was a very tall and stern young man in a business suit. Just when Betjeman was in the middle of a passionate tirade against the 'ugliness' of a nearby cinema, Gray stepped into the path of the stranger and asked him, 'Where are you going now?'

The young man, trying hard not to seem startled, managed to emit a cautious 'Er...' before Gray went on: 'How's the boss? Well is he?'

The young man, now looking somewhat pale from a mixture of insecurity and confusion, could only utter another 'Er...' before Gray continued: 'Give him my regards,' patting the man's shoulder firmly. 'Tell him you've seen me and I'll be in one of these days!'

Gray then let the now-dazed stranger move on, and he resumed his stroll with Betjeman. 'You know him?' inquired the intrigued poet. 'Never seen him before in my life,' replied the blank-faced comedian.

Betjeman, having long been familiar with his new friend's inscrutable ways, merely nodded. 'That's humour,' he reflected. 'The unexpected.'

That's what it was always like with Eddie Gray. No one else ever knew what to expect, and, quite often, neither did he. He just lived. He just laughed.

His influence would be far more pervasive and profound than many now, who are ignorant of him, might think. His mock-magic act would be emulated by Tommy Cooper; his mixture of French and English would be picked up and popularised by the 'father of Franglais' Miles Kington; his off-duty mélange of dottiness and deviousness (as well as his on-duty appearance) would be adopted by Vivian Stanshall; and his irreverence, invention and deconstructive knowingness would be assimilated greedily and gratefully by Spike Milligan, The Goons and Monty Python.

He was Eddie Gray, and they were Grayesque, but he was, pardon mon French, très magnifique.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreLife Is A Circus

Encompassing three hugely popular double acts, The Crazy Gang were one of Britain's best-loved, most enduring variety troupes - their antics delighting audiences for over three decades from the early 1930s and their career taking in numerous Royal Command performances. Their efforts to save a struggling circus provide the laughs in this uproarious comedy, also starring Goldfinger icon Shirley Eaton and featuring Flanagan and Allen's rendition of their greatest hit, Underneath The Arches. Life Is A Circus is presented here in a brand-new transfer from original film elements in its as exhibited theatrical aspect ratio.

The Crazy Gang have been jacks-of-all-trades with Joe Winter's Monster Circus for almost as long as Joe has been on the road, and they're still hoping for a big break. But Joe has hit hard times: his equipment is mortgaged, most of his acts have deserted him and even the elephants have walked out. So the Gang set about finding a way to save the circus... and come up with a typically novel solution!

First released: Monday 11th November 2013

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 81

- Catalogue: 7953966

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.