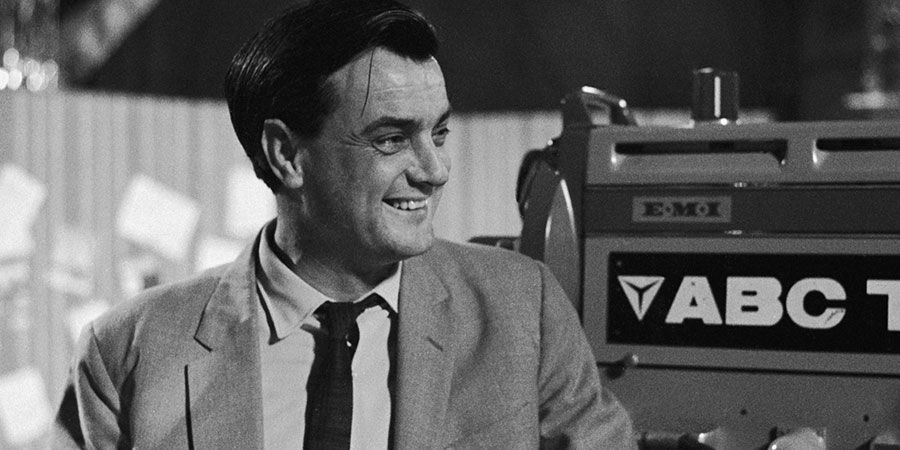

Happy birthday, Eddie Braben

To those who insist that you can't be a success in show business without being a hard, ruthless, self-obsessed individual, there is a simple two word answer, and it's a nice two word answer. That answer is: Eddie Braben.

Born on 31st October 1930, he would have been ninety this year, and, seven years since his death in 2013, is still keenly missed - not only because of the talent that he had, but also, and even more so, because of the person that he was.

Some people try to use comedy to be cruel, or to seem superior, or simply to dress up their hate as humour. Eddie Braben used comedy honestly, harmlessly and humanely. He just wanted to make people laugh, and make them feel better, and he was a master of his craft.

The long list of those who benefitted from his writing, at some time or other, is impressive in itself, ranging as it does from Spike Milligan to Peter Sellers, from Bob Monkhouse to Bob Hope, from Frankie Howerd to Larry Grayson, from Beryl Reid to Alison Steadman, from Les Dawson to George Burns, from The Two Ronnies to Little & Large. It is, however, the work that he did for not one but two bona fide British comic institutions, Ken Dodd and Morecambe & Wise, which cemented his status as one of the country's greatest solo scriptwriters.

It was not just the stature of his subjects that made his work so significant. It was also the nature of his engagement with them.

He was exceptionally empathetic. Many other writers would write for an existing image. Braben would write for an authentic individual.

Before Braben started writing for them, his subjects accepted a persona imposed from the outside. After Braben started writing for them, they embraced a persona from the inside. Before Braben they were held captive by quotation marks. After Braben they were liberated by life.

How did he get such a gift? He was probably born with it.

It helped that he was Scouse. Born at 13 Brenton Street, part of the inner-city area of Liverpool known as The Dingle, and brought up nearby at 24 Monkswell Street, he was the only son of Ted Braben, a butcher on St John's Market, and Catherine Stoddart; and he was immersed more or less from birth in the indomitable optimism, generosity and classic quick-wittedness of a working-class culture that cut through any pose or pretence like a sharp knife sent through tripe.

Billy ('The Mirthquake') Matchett (pictured), a popular local comic, was a distant relation, and Bruce Williams, an undertaker who wrote uplifting songs for George Formby under the nom de plume of Eddie Latter, was a family friend. In truth, however, there was no one in the extended Braben family who was lacking in one-liners as they worked their way through ordinary daily life.

'Come away from the window,' his father would shout in the house, 'people outside will think it's a pet shop!' Eddie would grow up thinking that it was completely natural to combine communication with comedy.

Academic communication, however, would prove itself to be quite another matter. Educated at Matthew Arnold Primary School, Dingle Vale secondary modern school, and Ellergreen high school, Eddie failed to impress as a student, later describing himself as 'as thick as the leg of a billiard table'.

It was the wireless, with its rich mixture of vivid sounds and hinted visions, which taught him the most during his childhood, encouraging a natural inclination to play with words and comic contexts. Sticking his ear close to what his father insisted was the best radio set a man could buy - 'On a clear night you can get Birkenhead' - he would absorb every word that he could make out from the likes of Band Waggon, Hi-Gang!, Mr Muddlecombe JP, Variety Bandbox and ITMA.

A three-year period spent as an evacuee in the village of Gaerwen on the island of Anglesey in Wales, from where he was taken each week to see radio shows being recorded at the BBC Variety Department's wartime base at Penrhyn Hall in nearby Bangor, further fuelled his fascination with the medium. 'It was watching the performers stand there, reading from their scripts, that brought it home to me even more than before,' he told me. 'I realised: it was the words that had the power. It was the words that were giving you the pictures. It was the words that were making you think.'

After leaving school in 1945, Braben - still listening, still dreaming - worked at Ogden's tobacco factory in Everton until the intervention of eighteen months' national service, which he spent as a dishwasher at RAF Kenley in Surrey. Upon returning to civilian life, he had an unsuccessful trial to play for the team that he supported, Liverpool Football Club ('I've seen better legs on a card table!' shouted one red-and white-scarved wag as he sadly departed the pitch), and then, reluctantly, joined his father on the busy and bustling St John's Market (a breeding ground of wisecracks and backchat), running a fruit and veg stall. Writing comedy, however, remained a burning ambition.

'I used to stand there writing jokes on the back of paper bags while the "customers" walked past,' he would recall. 'We used to get lots of performers come to the market when they were performing at the Empire, so I always hoped I'd get a chance to sell them some material. In the meantime I'd just keep turning the oranges around so the rotten bits didn't show!'

His chances of realising his dream already seemed slim by the early 1950s. There was, for one thing, a marriage - to Mavis Graham, a shop assistant - in 1953, and the birth of a son - Graham - the following year. It was hardly the right time to push for a precarious career in show business. One unexpected event, however, would challenge that thought, and change the rest of Eddie Braben's life: he met a young comedian called Ken Dodd.

Dodd had only recently turned professional, and, as an act, was very much a work in progress. Described by some local journalists as 'a burlesque comedian', by others as 'a musical oddity' and by a few as 'a crazy comic', he was like several jigsaw puzzles broken up and thrown together into the same bag.

Drawing on all of his Liverpudlian comic heroes, he would sometimes try to look and act like the droll Billy Bennett (jacket too tight, trousers too long, big hobnail boots and a succession of saucy monologues) or the characterful Robb Wilton (a ruffled, slope-shouldered suit, a fidgety manner and a fastidious mode of expression) or the slick and fast-talking Tommy Handley (smart suit, sharp enunciation), and sometimes more like the affable Arthur Askey (very ebullient, rapid and relentless gag-telling with plenty of audience interaction) or the rather urbane Ted Ray (a much dryer and more reserved style of delivery, with more musical material), and, increasingly, he would try to blend together elements from all of them (along with such traditional and typically playful Scouse phrases as 'diddy men' and 'jam-butty mines').

By the time that Braben first met him, Dodd already had the wild hair, the buck-toothed grin and the mock-music hall monikers ('Professor Yaffle Chucklebutty, Operatic Tenor and Sausage Knotter' was a favourite). Far from being a blank canvas, he was a cluttered canvas.

When Braben began writing him some new material, however, it soon became apparent that the scripts were sculpting a simpler, sharper, more distinctive style of persona. The oddity became more Doddity.

Sharing the same range of social and cultural references, Braben could not just see what Dodd had in common with past performers. He could also see what might help to make him different from them.

Dodd had studied other stand-ups. Now Braben studied Dodd.

It was obvious, as a consequence, that the writer had found his muse, and the performer had found his medium. Both knew that they had to work with each other.

Forging a professional relationship that would last for fourteen years, the two young men thus served as the ideal stimulus for each other's nascent talents. Dodd, with his insatiable appetite for original material, pushed Braben to new heights of productivity, demanding a seemingly endless supply of material ('It was Planet Frenzy,' said Eddie, 'at a thousand miles an hour'). Braben, being perfectly attuned to the range, tastes and rhythms of Dodd as a person as well as a performer, helped clarify his character, providing precision to his prolixity while furnishing him with the drolly distinctive vocabulary that best conveyed his wit.

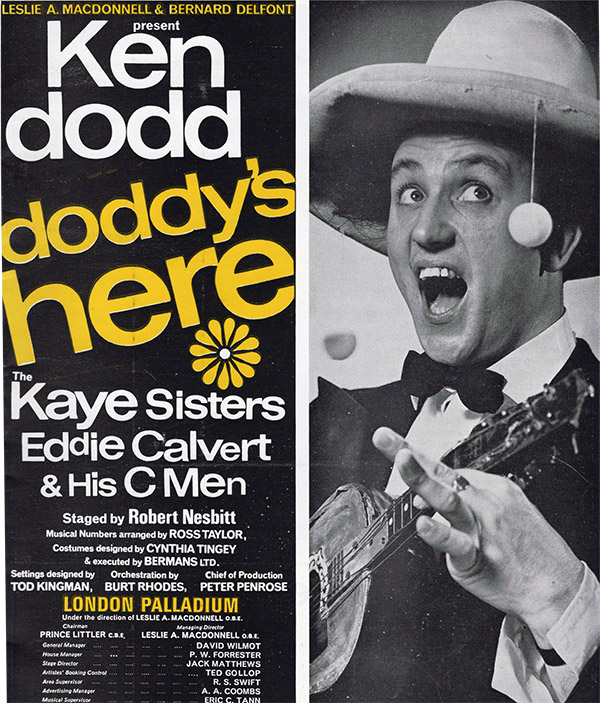

The success that they went on to share was remarkable. There were numerous television and radio series, regular stage shows, and, in 1965, a record-breaking 42-week residency at the London Palladium. Hailed by one of many appreciative reviewers as 'the finest patter comedian since Max Miller', and by another as a master of a 'sort of audience hypnosis', Dodd was bowing to standing ovations every night, while Braben was standing in the wings delighting in witnessing such an exceptionally warm response.

It was an extraordinary time for Liverpool in the country's popular culture. Rubber Soul was topping the charts, and Doddy's Here! was dominating the West End. In a decade when The Beatles were charming the nation with northern songs, Dodd and Braben were charming it just as deftly with northern comedy.

There was even one brief but memorable moment when the two Liverpudlian power bases found themselves sharing the same theatre's rehearsal space, and there was a sort of 'Scouse Off' between John Lennon and Eddie Braben. 'Do you always laugh at your own jokes?' asked Lennon, peering provocatively over his glasses. 'Why not?' Braben replied swiftly with a suitably defiant stare. 'I laugh at your songs.' The two men then started grinning at each other, the kindred spirits clicked, and a friendship of sorts was formed.

The work with Dodd went on, but their partnership was growing more complicated. The star was now locked securely in the cell of celebrity, a willing prisoner of his hard-earned fame, while the writer now had more than a singular vision to consider.

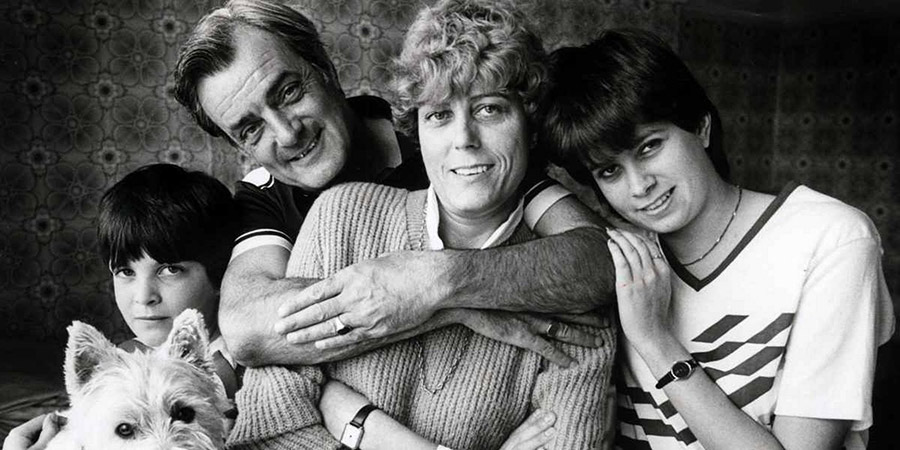

Braben - whose first wife had died in 1958 at the tragically young age of just thirty - had recently married again, to Deidree ('Dee') Cox, a 'honey-voiced' singer/dancer with whom he had fallen in love more or less immediately. Dodd, rather ironically, had been the one who had introduced them, but while he continued to obsess about his shows, Eddie was starting a new family (he and Dee would have two daughters, Jane and Clare).

Braben would never stop admiring Dodd, and being protective of him, always insisting that he was the 'funniest stand-up comic of all time'. He did, however, stop being able to write for him.

Money was the main problem. While Dodd was getting more of it, Braben was getting little of it, and sometimes none of it, because of his chronically insecure partner's infamously parsimonious ways.

While it is far too harsh to suggest that their relationship, over the years, had grown more like that of master and slave, it is probably fair enough to claim that Dodd had become increasingly demanding whilst seeming (no doubt quite unintentionally) increasingly disrespectful of his professional partner, treating him more and more like an automated joke machine than a talented and loyal friend. As the BBC executive Bill Cotton would later reflect, the driven Dodd's round-the-clock commands to his writer could seem akin to 'how a budgie treats its toy at the bottom of its cage'.

True to his decent nature, Eddie would never talk publicly about the real reasons for the split. He said at the time that it was simply down to the fact that he wanted to test himself writing for television while Dodd still preferred touring the theatres, but the truth was common knowledge in show business circles.

It meant that when Morecambe & Wise were abruptly abandoned by their own scriptwriters, Dick Hills and Sid Green, Bill Cotton was one of the first to know that Eddie Braben was available for a new, and better-remunerated, challenge. 'I realised that Eddie wasn't a conventional gag writer,' Cotton later told me. 'What Eddie wrote was something very unusual, not stand-up - Ken used it for stand-up, but if you really listened to it, you could make pictures out of it. So I had no doubt that he could adapt for a double act.'

Neither party, initially, was anywhere near as convinced as Cotton that the combination would be a good fit. Morecambe & Wise, while respecting Braben greatly, saw his main strength as a patter specialist, and Braben, while appreciating the progress that the pair had made since he had first seen their 'dire' act in the 1950s ('when they were so far down the bill I thought they were the printers'), remained underwhelmed by their recent work on ITV. It would only take about an hour at Television Centre, however, for a rare rapport to start to arise.

Braben, especially, could tell very quickly that this was the project for him. Meeting the double act in Bill Cotton's office, he did what he had done with Dodd and simply paid attention to the real people.

'I sat and watched the two of them - the way they spoke, the way they behaved, and just the way they were with one another,' he explained. 'And I knew then and there exactly what was missing from the Eric and Ernie I'd been watching on television. It was the affection - the warmth and affection. On television they'd been playing this niggly sort of couple. But in real life they were proper friends. There was genuine and honest affection between them - they were bonded together closer than any two brothers I had ever met. So I knew straight away: that was what I wanted to bring out. Drop the act and focus on the friendship.'

Morecambe & Wise, in turn, realised that the new partnership would work when they read Braben's sample script. For one thing, it was a complete, coherent and cleverly structured text - which, after years of having to shape a show out of the fragments of ideas and half-finished sketches that Hills and Green had tended to contribute, struck the two of them as the kind of professionalism they had been craving. For another thing, it made them laugh, such as the opening spot, which included dialogue such as this:

ERIC: I went to Somerset House.

ERN: Is that where you go to change your name?

ERIC: Yes. I would have changed my sex, only that door was closed.

They already felt comfortable with their new writer. They knew that he understood them, that he could see inside them. The deal, therefore, was done. 'I felt as if my wife had given birth to a beautiful baby girl,' Braben would say about that moment, 'that I'd won the lottery and there was sausage, egg and chips for tea.'

As he had done with Dodd, Braben helped them connect with their comic souls. Whereas Hills and Green (two middle-class Londoners) had projected a southerner's idea of a northern relationship on to Morecambe & Wise, Braben (as a working-class Lancastrian) projected the real thing.

He wrote in their accents, drawing on their shared range of cultural and comic references, giving them a sense of authenticity they had previously lacked. He also developed them as a double act, evolving them from the traditional straight man/funny man dynamic into a richer and more characterful combination of the foolish man who thinks he is smart (Ernie) and the smart man who is happy playing the fool (Eric).

The change in Ernie was particularly noticeable. Whereas Hills and Green had kept him tied to the template of the American-style straight man and somewhat tough and tetchy comic feed - e.g. 'What happened next?' 'And then what did you say?' 'So what are you going to do about it?' - Braben saw a kinder, warmer individual, very sharp about show business but perhaps rather naïve about the world outside of it, and brought more of the real spirit to the screen.

'My Ernie,' Braben would explain, 'would never say, "Ooh, that's a pretty dress". He'd say, "That's a nice frock". "Frock" was very old-fashioned, very Ernie. He wouldn't say, "Mathematics". He'd say, "Sums" or "Adding up and takeaways". So when the on-screen Ernie would get a bit pompous and pretentious, words like "frock" would let it slip that he was really just this ordinary working class man. He'd end up puncturing his own ego. There was some vulnerability there. He wasn't this hard and harsh Bud Abbott type at all. In real life, if someone told Ernie a blue joke he'd probably blush, so there was more of an innocence about him - certainly compared to Eric - and he really did still dream of going to Hollywood, so all of that was grist to the mill. My Ernie, on the screen, became much nearer to the Ernie I knew, obviously with exaggerations for comic effect.'

As an appreciative Eric Morecambe would later put it: 'What Eddie Braben did for Ernie was to make him into a person. Before, anybody could have played his part. Not now. Ernie is his own man.'

Eric, ostensibly, required less revision, but, to a certain extent, Braben changed him, too. He gave him a more coherent comic core, a more balanced kind of character.

'Up to this point,' Eddie would tell me, 'Eric had sometimes been obliged to seem a bit dim and dopey on the screen, a bit gormless. He was often having to be put right and pushed around by Ernie. That was nothing at all like the real Eric. In real life, Eric had this intelligence, and this razor sharp wit that, if he'd wanted it to, could have destroyed someone, so I wanted my Eric to have a tiny bit of danger to him as well. That playful pat on the cheek - it could so easily have been followed by a much, much harder slap. It never was, but, when he did pat Ernie, or took hold of someone else's lapels, you wanted that hint of further aggression. Crafty, cunning, charming, mischievous, unpredictable, a little bit dangerous - that was more like Eric.

The focus, in short, went from an artificial act to a believable friendship, gradually narrowing the gap that separated the onscreen Eric and Ernie from the off-screen Morecambe & Wise to the point where it had practically disappeared.

Audiences, as a result, warmed to them more freely and deeply than ever before. They walked on stage together looking and sounding like the two old friends that they really were; they reminisced and teased each other about their shared northern past (mildly stylised via the mythic Milverton Street School, next-door neighbour Ada Bailey and the always-busy chippy on Tarryassan Street); they would buzz about and unnerve their famous guests like a pair of cheeky scallies; and, just as they had done during their early years on tour, they would share a bed together and have an idle chat ('If it's good enough for Laurel & Hardy,' Braben told them, 'it's good enough for you').

They would also, of course, deliver, quite beautifully, all of those wonderfully characterful, cleverly rhythmic, and artfully silly lines:

ERN: Rocky felt a tingle of excitement as his executive jet touched down in Amsterdam. It was his first visit to Italy.

ERIC: That's knockout, that, Ern.

ERN: Yes, another mammoth spectacular.

ERIC: Aren't they all?

ERN: My mother had a Whistler.

ERIC: Now there's a novelty.

ERN: I've extended my repertoire.

ERIC: It didn't show from back there.

FRANK: I have a long felt want.

ERIC: There's no answer to that!

GLENDA: All men are fools, and what makes them so is having beauty like what I have got.

ERIC: In my opinion, Ern, you could be another George Bernard Priestley.

ERN: Shaw.

ERIC: Positive!

GLENDA: Would you like to rest your head on my lap?

ERIC: If you can get it off - yes!

VANESSA: Have you got the scrolls?

ERIC: No, I always walk like this.

ERN: You'll have sciatica in the morning.

ERIC: No I won't. I'll have Shredded Wheat like everybody else.

ERIC: He's not going to sell much ice cream going at that speed!

Eric Morecambe would describe Eddie Braben, sincerely, as 'a gift from heaven,' and both he and Ernie Wise never hesitated to put on record how much they relied on his wit and work, but writing for them and their show put a strain on him that was sometimes unbearable. It had been tough enough crafting comedy for Ken Dodd - 'The ratio was at least seven gags a minute, every minute, for shows that could go on for hours. It was one hell of a lick and well worth an ulcer!' - but once he started writing for Morecambe & Wise, at peak time on TV, he was immediately plunged into a schedule that obliged him to come up with enough comic material for eight 45-minute shows in the space of just seven weeks, followed by a high profile seasonal special.

Every script was slaved over inside the study of his West Derby home in Liverpool, toiling away on the typewriter (while smoking forty cigarettes a day and drinking gallons of tea) until, quite often, he fell asleep slumped over its keys. A doggedly two-finger typist, his right forefinger ('the one that did all the work') ended up permanently disfigured like a slapped and swollen pork sausage, with the knuckle split in two, from the relentless pressure of pounding out the words.

If ever he struggled to overcome a writing block, he would take a plain piece of paper, draw a square on it, stick it on the wall he was facing and imagine that it was a television screen. Then he would stare at it, imagine two figures entering inside, 'and let them do whatever they had a comedy mind to do'. Then he would start typing again.

Even the show's producer, John Ammonds - probably the most meticulous editor of comic material British television has ever seen (writers used to joke that if you sent him a Christmas card, he'd send it back with suggestions for re-writes) - would find himself worrying about the effect it all was having on Eddie's health:

Eric and Ernie could really pile the pressure on to Eddie at times - when they were feeling the pressure, too - and I'd have to remind them: 'Look, it's not like a tap, you know. You don't just turn it on and get a load of great material and good sketches and good gags gushing out! It's a lot of hard work!' It takes a very rare talent, actually, to write comedy - top class comedy - under that sort of pressure. It's rather like asking Beethoven, 'Can you knock off another nine symphonies in the next six months, because, you know, we need them?'

There was one occasion when Braben snapped back: in the middle of one week, burdened by one too many requests for revisions, he sent back a package containing forty blank pages, with a covering note that read: 'Fill these in - it's easy!'

There was another occasion, however, when Braben simply snapped: in 1972, after working for such exceptionally long stints that he started having hallucinations, he suffered a major nervous breakdown. He was forced to rest for several months, while Morecambe & Wise had to feed off lesser talents in his absence.

Astonishingly, once recovered, he would not only go on scripting the vast majority of the subsequent Morecambe & Wise shows singlehandedly (maintaining the programme's progress, helping to keep topping each new triumph, and entertaining huge audiences amounting to about half the nation in the process), but he also somehow found the time and energy to write (and appear in) his own string of BBC radio shows: The Worst Show On The Wireless (1973-5), The Show With Ten Legs (1976-81), and The Show With No Name (1982-4). He still suffered from the strain of maintaining his own high standards, but he simply never tired of making people laugh.

When, with the death of Eric in 1984, his work for Morecambe & Wise was finally over, Braben would keep writing on into the late 1990s, supplying material for the likes of Bruce Forsyth, Mike Yarwood, Jimmy Cricket, David Frost, Ant & Dec, and (the butt of so many of his jokes) Des O'Connor. The pace slowed a little, and, mercifully, the pressure lessened, but the pleasure of crafting comedy remained profound.

'It's the greatest way to earn a living,' he said. 'I sit here and think to myself - it's coming out of my head, down my arms, on to the typewriter, down to London, and out of the telly. And it will make an awful lot of people laugh. That gives you a considerable amount of satisfaction.'

Even in what amounted to semi-retirement, when he and Dee moved permanently to their old holiday home on the Welsh Riviera of the Lyn Peninsula, he never stopped writing. He couldn't stop writing. Comedy kept bouncing around in his brain just as surely as blood kept pumping around his body.

I had the rare pleasure of talking fairly regularly to him over the phone in those later years, and, during our conversations, he would often mention, quite matter-of-factly, the routines he was still devising for Morecambe & Wise. 'I just thought of another one this morning,' he'd say, and then he'd suddenly launch straight into a brand new Eric and Ernie bedroom sketch, perfectly pitched, echoing exactly both Eric and Ernie's distinctive inflections, and, as always, it was wonderfully funny.

It was good that, when some of his old sketches were revived for a stage play (The Play What I Wrote) in 2001, and when he finally got around to writing a memoir (The Book What I Wrote) in 2004, both projects attracted plenty of warm reviews, because it let him know, at least a little, how respected, and loved, he was. In truth, however, he should have been celebrated much more - not just for what he had done, but also for how he had done it.

Beneath the statue at Anfield in Liverpool of the legendary football manager Bill Shankly, one of Eddie's own heroes, it says: 'He made the people happy'. No sentiment could better suit Eddie Braben, too.

He was never one for a fuss - 'When you're eulogised for being a great writer, as I are, it can be a burden' - but a fuss is what he deserves for all of the fun that he created. It is only right, therefore, that we continue to remember the birthday of this most modest of men, and never, ever, forget his rare and special contribution to British comedy.

Morecambe & Wise may have brought us sunshine, but it was Eddie Braben who parted the clouds.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreMorecambe & Wise - The BBC Collection

Morecambe and Wise are the greatest comedy double act ever to grace our TV screens. The fabulous mixture of sketches, musical numbers, insights into their 'home' life and the plays 'wot Ernie wrote' brought them audiences in the millions.

On stage they were living legends with Eric's raised eyebrows, Des O'Connor jibes and cheeky catchphrases putting every audience in the palm of their hands. And, of course, the stars - from Shirley Bassey and Elton John to Laurence Olivier and Glenda Jackson - lined up to join in the fun.

This box set includes all 9 series and five Christmas specials, and features every surviving moment of Eric and Ernie's BBC career including the legendary Singin' in the Rain, the famous André Previn appearances and the acclaimed breakfast sketch - as well as every shoulder-and-cheek slap, Luton Town reference and "Not Now Arthur!" in between.

Note that only a select number of extracts from the first series remain in known existence in BBC archives, and so Series 1 is presented here incomplete.

First released: Sunday 3rd October 2010

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 20

- Catalogue: BBCDVD3275

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Eddie Braben - The Book What I Wrote: Eric, Ernie And Me

The hilarious memoir of much-loved, highly successful comedy writer Eddie Braben, whose scripts for Morecambe and Wise catapulted the incomparable duo to stardom.

The key figure behind the success of Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise, scriptwriter Eddie Braben has written his autobiography - with the inimitable, timeless humour, warmth and affection for Eric and Ernie of that wonderful bygone era which made their classic sketches so successful.

From Liverpool to London and on to Snowdonia, Braben peppers his story with wonderful anecdotes about the original straight man and his amiable sidekick.

The Book What I Wrote is as much a unique biography of the charismatic Eric and Ernie as it is an autobiography of the man on whose gags their success was made.

First published: Monday 16th August 2004

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 304

- Catalogue: 9780340833735

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Monday 11th April 2005

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 304

- Catalogue: 9780340833742

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 7th December 2017

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Catalogue: 9781473682863

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.