Up and away: The big fall of Duggie Small

Few things have proven so distortive, when it comes to the perception of genuine potential, as the television talent show. Rather like the mad scientist who manages to animate the inanimate, and then regrets the extent of their Promethean powers, the TV talent show, historically, has been so recklessly desperate to deliver results that it has hyped up some of its so-called successes so much that, once the studio-powered wind has been cut so rudely from beneath their wings, they have been left to plummet helplessly back down to the cold and hard ground of obscurity.

A sobering case in point is the story of the comedian Duggie Small. On the night of 13th December 1986, at the end of an exhaustive and exhausting four-month-long process that had seen some seventy candidates (out of the three thousand that had originally auditioned) compete for a chance to make a name for themselves in show business, this diminutive 5ft 2inch Scottish comic eclipsed all eleven of his fellow finalists to be crowned the winner of the latest series of ITV's New Faces. 'You're a star, superstar', the theme song blasted out as the applause rang round the studio, 'On you go, it's your finest hour/And I know that you'll go far/'Cause you're a star!'

The reality would be so very different. Of all those performers who fell for this dubious fast route to fame, few, if any, would be chewed up and spat out quite as quickly, and as callously, as Duggie Small.

Born Alexander 'Alec' Cairns in 1946 in Saltcoats, Ayrshire, he came from a very musical family (his father, an accordion player, and his mother, a pianist, played semi-professionally, and his sister would go on to train as an opera singer), but he started out in adult life as a jockey, travelling to Newmarket to serve his apprenticeship. In a professional career that encompassed no fewer than four hundred rides, however, he only won two races ('I think I rode a lot of bad horses', he would later theorise), but suffered multiple injuries that included a fractured ankle and ribs, a broken shoulder on five separate occasions and a broken collarbone on six, as well as several concussions. When, at the start of the 1970s, he badly injured his back following yet another fall during a meeting at Leicester, he finally, wisely, decided to call it a day as far as horse racing was concerned.

It was while he was recuperating back home in Scotland that he came up with the idea, following a particularly convivial family get together, to team up with his brother, John, to form a 'comedy instrumental duo' that they called, logically enough, The Cairns Brothers. John played the guitar, Alec (who had already moonlighted as a musician in a showband called The Phoenix during his time in Newmarket) the drums, and both of them did some comedy. They entered and won a couple of local talent contests - the second of whose judges, somewhat bizarrely, were the football managers Jock Stein and Tommy Docherty - and felt encouraged enough to cross the border and start touring England's northern club circuit.

They kept busy, did quite well (Tyne Tees Television, apparently, scouted them for possible inclusion in one of its variety shows, although they never actually got to appear in front of the cameras), and received a sufficient number of positive reviews to convince them that they were pounding the right path to progress ('It was a good day for me,' Alec would reflect, 'when I fell from that horse'). After just over two years of treading the boards, however, they realised, reluctantly, that they were destined to dwell on a low plateau, and in 1973 The Cairns Brothers packed up and went their separate ways.

John, who was suffering from homesickness, returned to Scotland, but Alec, who had always been the more exuberant performer of the two, stayed put, changed his name to Duggie Small, and duly set off on a solo career as a comic and impressionist. He did not have much of an act in terms of material (this would remain both his strength and his weakness, in the sense that it made him prefer props to patter, helping him to seem different while hindering his ability to accumulate solid and coherent comic content), but he believed the power of his personality would protect him as he started to build up some routines.

Like so many budding performers, Small was an idealist rather than a materialist, convinced that the sheer force of will would wrought the right changes on reality and send opportunities his way. If people didn't yet know him, he would bring himself to their attention, and he would find a way to make them like him.

As early as the summer of 1973, he was being advertised in the trade papers as 'the "big" hit nationwide' - which, aside from its ironic reference to his size, begged a couple of questions: namely, what actually was the nature of this 'hit', and what was the evidence that it was 'nationwide'? Such pedantry probably didn't bother young Duggie, who had thoroughly embraced the old showbiz maxim that one has to exaggerate in order to accelerate.

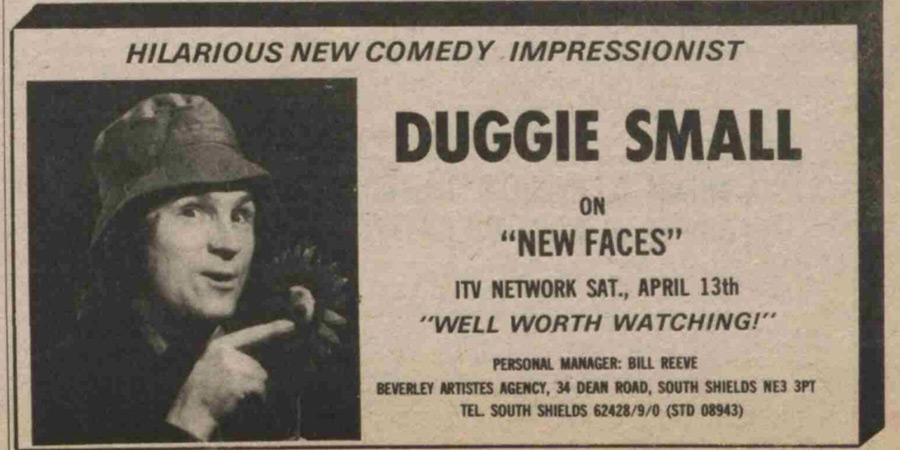

It seemed to do the trick. The following year, on 13th April 1974, Duggie Small did indeed, quite factually, reach a nationwide audience, albeit without him being hailed a hit of any particular proportion. The showcase for his performance was a television programme by the name of... New Faces.

It was the second heat of the series, and Duggie found himself up against the vocal-instrumental trio Harvest, the eight-piece soul band Sweet Sensation, the singer Meg Johnson, the pianist/singer Mike Alexander, the comic Rick Lomas and something called The Reg Coates Experience. Duggie, as usual, offered what he called 'organised lunacy' (which consisted, then and later, of far more lunacy than organisation): he attempted a couple of impressions, ran around a lot and relied on props to serve up some quick-fire gags.

He lost, but the exposure was sufficient to generate at least a little more publicity. Even failing on television, in those days, justified one advertising oneself as having 'been on television', and Small - or his management - certainly built on that argument to the extent that they started billing him as the 'top comic impressionist from New Faces'.

It did not, however, seem to help much in terms of improving dramatically the kind of venue that wanted to book him. Anyone eager to sample the Duggie Small experience would have to seek him out in such places as the Ex-Servicemen's Club in Bonnyrigg, the New Northern Social Club in Ashington, the Musters Hotel in West Bridgford, the Ebbw Bridge Club in Newport and the Leyland Scotland Sports and Social Club in Blackburn.

He was actually, by now, getting consistently good reviews. 'Duggie is entertainment with a capital "E"' wrote one enthusiastic observer. 'Working at a tremendous pace he combines his original talent with impressions of Tom Jones, Mick Jagger and Michael Crawford. After an hour on stage Duggie looked as if he could have kept going for at least another hour without showing any outward signs of strain. Where does he get his abounding energy from?'

The problem was that, like so many other hard-working entertainers on the circuit, he seemed to be trapped on the treadmill, always in action yet going nowhere. At some venues he was praised to the skies; at others he was pelted by pies. The experience was growing; the hope was atrophying.

He thought his luck had changed when the production team behind another ITV talent show, Opportunity Knocks, announced plans to travel up to Glasgow to audition the best of the local acts, and he was invited to take part. Although his performance was well-received, he failed, in rather puzzling circumstances, to get picked for the actual televised programme. 'Hughie Green', he later recalled, 'said his famous last words..."Tremendous, son...goodbye", and that was it.' The TV crew went back down south; Duggie Small was left behind up in the north.

In 1977, after his ever-supportive wife, his childhood sweetheart Helen, talked him out of quitting the business completely ('I've wanted to pack it in many times when I couldn't see the point of continuing', he would say. 'But she has kept me on the right road, persuading me to keep plugging away'), he found himself a new personal manager, Joe Blackwood of Lanarkshire, and resolved to push even harder to get his breakthrough.

Aside from a brief appearance the following year on Tyne Tees TV, however, he seemed, if anything, to be slipping backwards. His manager was getting him plenty of bookings, but they were mainly in Scotland at a stage in his career when he had been hoping to extend his engagements over into England.

When the Eighties began, he was still slogging away in semi-obscurity, playing afternoon gigs at the Kirkaldy Travel Club. By the summer of 1980, finally tired of trying, he decided to give up show business and do something else, undergoing training as a barman and making plans to open up a guest house in the North-East of England.

The need to stand on a stage and entertain, however, proved too strong to shake off, and within a few months he had signed up to a small English agency, Angle Entertainments of Rotherham, made some changes to his image (swapping his traditional tuxedo for a more relaxed-looking tracksuit and trainers), and was back touring the halls, dreaming once again of being discovered by someone with the power and passion to turn him into a star. There was a spell as a Butlin's Redcoat at a holiday camp in Ayr, and then a flurry of engagements south of the border in and around the Newcastle area (where he and his family had settled), followed in 1983 by a brief appearance on an ITV comedy show called Make Me Laugh.

Slowly but surely, he was attracting more attention. In November of 1985 he was one of the club performers invited to appear at a major event designed to showcase up-and-coming talent, held at the Keresforth Hall Cabaret Bar in Barnsley and attended by some of the country's leading TV and theatre producers, directors and casting agents. His own performance there, which featured a new(ish) routine he had devised impersonating all of the Nolan Sisters, was judged one of the hits of the night, and ensured that his name, from now on, would be logged on various long lists of new acts worth trying.

It also won him an invitation to audition, once again, for New Faces. Twelve years on from his previous disappointing appearance on the show, he was determined to seize the opportunity this time around, and promptly went ahead and did so, coasting through all of the test sessions and securing a place in one of the televised episodes.

On 19th September 1986, the series began. Heat 1 saw Small compete with five other acts: the tap-dancing troupe Hartley's Hot Taps; the comic Kelly Fox; singer/pianist Jody McStravick; the pop group Dead Giveaway; and the singer Michele Breeze.

It was not, in truth, a terribly memorable procession of talent. 'I didn't think any of the performers were particularly impressive', wrote one reviewer. 'The best part of the show was the amazing electronic scoreboard.'

The 'pint-sized' Duggie Small, nonetheless, ended up triumphant, winning not only the largest proportion of the studio audience vote on the night but also, once the postal ones were collected and counted, the biggest share of the votes of the viewers at home. He had, at long last, made it: he was coming back for the final.

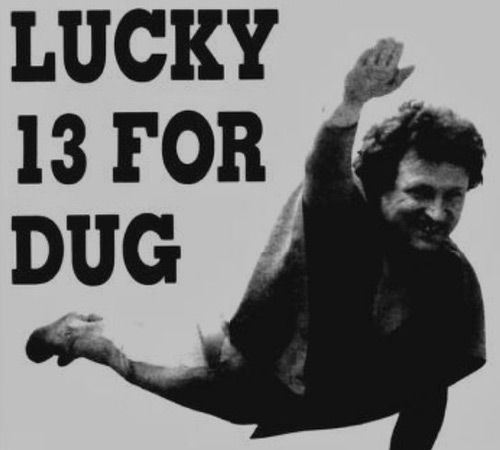

Being a fairly superstitious individual, he felt that fate, this time around, was on his side. The show, he noted, was the thirteenth of the series, it was going to be transmitted on the thirteenth day of the month - and he happened to live at... number thirteen. 'You can guess', he said excitedly, 'what my lucky number is!'

Broadcast live from the Birmingham Hippodrome (with the cameras, by the look of it, stuck at the back of the stalls), the final was hosted by New Faces alumnus Marti Caine (winner, 1975), and featuring as judges were the singer/actor Millicent Martin, the comedian and New Faces alumnus Jim Davidson (winner, 1976) and the theatrical impresario and professional Evertonian Bill Kenwright.

It was a very peculiar affair that seemed to transport the viewer back to the 1950s and the early days of commercial television, with the 'borrowed' theatre setting, the limited range of camera angles and close-ups, the muffled sound of the audience and the general air of barely-suppressed anxiety that infected every stage of the proceedings. The acute nervousness of Marti Caine, as the presenter, was made worse by the decision to make her race off and change outfits on multiple occasions throughout the show, although her sympathy and support for her fellow entertainers would be the one element of humanity in an otherwise soulless experience.

First up for consideration was a fleet-footed and loose-hipped young man from Oswestry called James Stone, who gave a spirited rendition of Honky Tonk Women whilst slavishly mirroring the dance moves of Michael Jackson. Next was a baggy-panted and toothy self-styled Scouse 'loony comic' by the name of Freddy Phillips, who twitched and gurned as if being attacked by a beaver whilst laughing raucously at his own jokes ('It's great here, innit!'). Third on was the affectedly named Julie A'Scott, a very intense soprano who treated the viewers to a medley of Andrew Lloyd Webber compositions.

There was a pause at this point while the wide-eyed judges were asked for their observations on the opening trio. Millicent Martin set a predictable tone of dottiness by opining that Stone had 'obviously a much better voice' than Michael Jackson, while Jim Davidson, eagerly picking up the baton of barminess, declared that Phillips was 'a very funny man', and Bill Kenwright announced that A'Scott was 'a bit special'.

The next three followed: Scott Randelle, a callow singer with a pained expression who, rather too enigmatically, was said to be attempting 'a 1986 version of an old traditional Scottish song'; Walker & Cadman ('a Cockney and a Lancashire lad'), whose routine was a kind of recurring nightmare of the most clichéd themes associated with bad comedy double acts (Marti Caine, as they departed the stage, said their names not once but three times in quick succession, as if seeking to cancel out some terrible spell); and 'Scotland's own' Maggie Dee, who did not so much sing as stage an on-screen intervention with her own sinuses.

There was another quick consultation with the judges after this, quite frankly, alarmingly poor trio of turns, and their reactions only added to the air of madness that was rapidly descending on the proceedings like a Hammer horror fog. 'She's another Barbra Streisand', a strangely serious Jim Davidson dubbed Maggie Dee. Neither Millicent Martin nor Bill Kenwright appeared to know how to react to such an astonishing assertion, other than to say nothing and just stare blankly ahead. Marti Caine, sensing that something was not quite right, decided it was probably best to cut short the whole sequence and speed through the next few acts.

'Next', she said, looking somewhat dazed, 'a young man from Staffordshire who decided to put some fun into violin playing...' It was, of course, the ever-grinning teenaged anagram Gary Lovini, playing Hooked on Classics very, very, fast while he gasped at how very, very, fast he was going.

Then the great moment arrived: the time for Duggie Small to take his place in the spotlight. 'You ain't seen nothing yet', Marti Caine warned as she reminisced about the previous appearance of this 'wee Scotsman' who had forced everyone 'into fits of laughter' in the earlier heats.

He then ran onto the stage, hitting himself repeatedly on the head with boxing gloves. His next move was to don a German military helmet, pick up a tennis racquet and announce that he was Boris Becker. These prop-oriented 'gags' kept on coming, including a really quite odd routine about how people from different professions would pick up a pound coin, and then, by way of a grand finale, he went into a telephone box, answered a call, and re-emerged as Superman - which was not, to be pedantic, very comedic as such, but, nonetheless, the audience sounded impressed.

It had been a peculiar performance for a comedian, with very little real content but plenty of manic energy, and it had not been helped by TV direction which too often had been too distant to capture his reactions. In those five minutes, nonetheless, enough mischievous charm had come through to make the act considerably more engaging than the ones that had preceded it - or, indeed, most of those that now followed it.

Those latter acts in question would comprise of the Carpenters-style musical duo High Jinks, the Neil Diamond-lite singer Wayne Denton, the raspy-voiced comic Billy Pearce and the impressionist Pauline Hannah. Out of these, Pearce was the most effective, in the sense that he packed his screen time with what he did best, or least-worst - tell gags - and, unlike the others, did not seem too much like another performer's tribute act.

The results section was even more chaotic and confused than the rest of the show, with a shattered-looking Marti Caine, pointing up at the mess that was the electronic scoreboard, struggling to 'explain': 'As you can see, the names of the twelve acts that have been in the final tonight are represented in the, er, stars round the edge of the board... along with, er, a scoreboard which will mark the scores as we go along, er, in the middle is the names, are the names, of all our regional, all our regional, panels...'

Eventually, after all the various sources of scores were finally collected and collated, Duggie Small was declared the winner. Such was the shambles of the production, his celebrations lasted about two seconds before the credits ended and the commercials started.

He wasn't bothered. The breakthrough had been made; he could not wait to build on his success.

The critics were by no means as sanguine as to his chances of achieving 'proper' stardom. One complained that his act was 'never anything more than end-of-the-pier stuff', another dismissed him as 'an averagely funny fellow', while a third hoped that 'someone, somewhere, remembers his name in a year's time', but then added, 'on the face of it, I doubt it'.

Small, however, continued to think big. While the others received nothing ('not even a vase', one moaned), his prize, aside from the publicity that was generated, was a contract with Central Television for his own show in 1987 (with a subsequent series acknowledged as a possibility). That was going to be the showcase in which he would prove how much potential he really had.

He warmed up for the solo show with an appearance on the BBC's high-profile Wogan chat show in January 1987. It was not, to put it mildly, a success, and it exposed, quite painfully, how premature was his prize-winning passage to stardom.

Still overly-reliant on his old over-exposed material, he started off with the puppets he used for his Nolan Sisters parody, then, when the studio audience failed to respond as well as he had expected, he tried some desperate-looking tumbles before ending, yet again, with his Superman routine. Obliged after this embarrassing flop to join the other guests on the sofa, he had to endure the further torture inflicted by the Italian opera diva Katia Ricciarelli, who glowered at him with undisguised contempt throughout the rest of the programme (his sad predicament would be alluded to, many years later, in the edition of Knowing You, Knowing Me in which a northern comic called Joe Beasley, with glove puppet Cheeky Monkey, dies a similar death on Alan Partridge's talk show: 'Your act is really poor - if you've got any sense of dignity you'll leave the stage!').

This was by no means a sudden problem for Duggie Small. It had been evident to anyone of any critical experience who had seen him perform at any stage over the past decade or more. 'I don't suppose I tell more than six jokes in my entire act', he had often boasted. When asked why, he replied: 'These days you have to give an audience more'.

The answer to that was surely that, before you give an audience more, you have to give it enough. Duggie Small's comedic house never had any solid foundations. It only stayed upright, when it did at all, by him racing around and around trying to stop all the walls from falling in.

He needed more jokes, he needed better routines, and he needed a stronger structure for his comic spirit. If, therefore, his newly-appointed TV mentors were going to do what they had promised to try to do and mould him into a proper star, then this was the kind of work that urgently needed to be done. The clock, however, kept ticking, and those tasks, in the most part, had still not been attempted.

Even elsewhere within the ITV network, after witnessing this unhappy on-screen incident, there were murmurs of concern about Small's forthcoming special. 'I feel very sorry for [him]' said the TVS executive John Kaye Cooper. 'He is a talented comedian - but it's so unfair to give him his own show straight away, without giving him the chance to develop and make the necessary mistakes every performer has to make away from the pressure of heading a peak time show.'

Ominously, inside the fidgety planning sessions for the forthcoming special, the production team, cranking belatedly into action, was now working hard to fit Duggie Small into a certain kind of format, instead of finding the kind of format that would fit Duggie Small. It was decided, for example, to change his image, dropping the tracksuit and putting him back into a traditional-looking dinner jacket. It was also judged necessary to send him to elocution lessons to remove much of his Scottish accent and make him more accessible to a broadly British audience (presumably the same broadly British audience that voted him to victory in the first place).

All of this caused delays. It had been reported at the start of the year that the show was slated to reach the screen in March. Nothing happened in March, however, nor April, and Central had fallen silent about all aspects of the project.

When, at last, a show was announced at the start of May, the contractually-promised solo show for Duggie Small had somehow metamorphosed into a showcase he was to share with several of the artists he had beaten. Entitled New Faces Winners - The Next Step, it was described as an hour-long variety show, starring Small but also featuring, among others, fellow finalists Billy Pearce and Pauline Hannah as well as Mervyn Jaye, an impressionist who had lost out to Wayne Denton in one of the earlier heats.

When the programme was broadcast, at 7:45pm on 30th May 1987, the sheer awkwardness of it as a production must have prompted the more invested of viewers to have wondered what on earth had happened during the prolonged planning stages. For one thing, the choice of supporting performers seemed downright perverse: if the aim really had been to highlight what was distinctive about Duggie Small - a quirky stand-up comic and impressionist - then why feature alongside him another quirky stand-up comic and two more impressionists? For another thing, it appeared equally odd that most of what was supposed to be a star vehicle for Small actually obliged him either to step aside for others to shine or else share some sketches and routines alongside them. What little screen time that was devoted to him and him alone offered no opportunity to do much more than reprise the best bits from his previous two New Faces appearances.

If the production team had predicted that Small was simply too limited a performer to build a show around, they certainly did an excellent job of finding a format that fulfilled that prophecy. Humiliatingly, it made him look like a guest on his own show, a winner now treated as an also-ran.

The critics, once they had viewed it, were not kind. One or two at least tried to sympathise: '[Duggie Small] may have a perfectly good act, and if he has we did not get any opportunity to judge it in this programme', complained one observer. 'Instead he was used as the link enabling other New Faces finalists to do their thing.'

Most, however, could not wait to damn the whole enterprise as a disaster. 'The next step for the lot of them will probably be the dole queue', wrote one reviewer, before adding: 'As for Duggie Small, it defeated me that he should ever have won New Faces in the first place, and this show only confirmed that this little man is about as funny as a rattlesnake in a lucky dip.'

Central, having shown practically zero duty of care to its own supposed star-in-the-making, promptly dropped him after this shambles of a show, but Small did not disappear immediately from the public eye. Vowing to be careful with all the money he had recently earnt (investing in a new bathroom for the family home at Gosforth was about as extravagant as he got), he took up the offer of a summer season in Scarborough, followed by a pantomime at Manchester, and continued to tell anyone who would listen how much he would 'dearly love' a television series all of his own.

By the end of the year, however, he was complaining of having had several offers of TV work mysteriously withdrawn, and said he suspected that ITV had 'snubbed' him. Blaming it on what, by his own admission, had been a 'disastrous' appearance on Wogan back in January ('I can only put it down to that'), he protested bitterly: 'I know I needed more TV experience, but they didn't give me a chance'.

He soon found himself back on the old provincial circuit, playing such modest little venues as the Dagmar pub in Witherwack. He did receive, very gratefully, an invitation to appear in a couple of short sketches on The Benny Hill Show during 1989, as well as a brief one-off spot on Sky Television's Derek Jameson Tonight show, but, rather than sparking a revival in his TV career, such excursions proved merely a passing diversion from touring the clubs.

The deflating experience of Duggie Small, post-New Faces, was not actually that different from most of his fellow contestants from the final. A 2011 BBC documentary on the class of '86 would reveal that all of them suffered, to some degree or another, from being abandoned so abruptly by their so-called star-makers.

Walker & Cadman, for example, broke up at the end of the 1980s and Vinny Cadman (who had found the brief burst of adulation 'better than food') tried to make it on his own, but the work soon dried up, he succumbed to alcoholism, went through three failed marriages, had a stint in prison for drunk-driving and then spent a year living in a rubbish skip before returning to performing at local caravan parks. Both Julie A'Scott and Gary Lovini ended up as cruise ship entertainers. James Stone, a very vulnerable and troubled soul, suffered from gross mismanagement, never saw most of his earnings, and was reduced to touring the bingo halls. Even Billy Pearce, who was picked up by one of the big talent agencies and given his own TV series, invested badly in a night club in Portugal, lost most of his savings and was then back to working on the northern club circuit.

Duggie Small did not appear in the programme on the grounds of poor health. He was still working, however, driving more than sixty-thousand miles a year to and from gigs, putting in stints at holiday camps, struggling through raucous hen and stag nights, and still doing much the same act, with much the same gags, that, all those years ago, had made him - as his posters continued to point out - 'the outright winner of New Faces'.

Duggie Small never, however, stopped dreaming of that TV series that got away. He devised several new starring vehicles, along with some game show ideas, and kept sending them in to production companies, rarely receiving any replies. He coped with the despair, but refused to abandon the hope.

Looking back now at what he tried and failed to do, it is hard to find him culpable of anything worse than naivete, excessive optimism and too much trust in others. All he did was take an opportunity that knocked for him, and then do, to the best of his current ability, what he was told to do.

As for the team behind New Faces and the broadcaster responsible for the prize it promised to its winner, the verdict surely has to be far sterner. They auditioned him, they chose him, they hyped him, they put him up for the public vote, they promised to reward him if he won that vote - and then, when he did, they didn't. Having portrayed themselves as all-powerful star makers, they looked at their raw material, found it wanting, and so, like potters objecting to the quality of their clay, they pounded it back down, dropped it in the bin and moved straight on to the next project.

The assumption that conscience is something that can be wiped clean at the end of each day is one of the worst characteristics of those who inhabit the solipsistic and remorselessly self-congratulatory world of show business. Unless and until that convenient conceit changes, then the pathetic fate of Duggie Small will still be lurking in the shadows for so many other hopeful souls who cannot resist walking through what they've been assured is an open door.

'You're a star', he had been told, and, as short-lived as that spurious stardom proved itself to be, he never would figure out why it had stopped so suddenly. 'Thought I was on my way', he would say, with a bewildered shake of his head, 'can't think what went wrong.'

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more