The Indomitable Don Estelle

How do actors win roles in sitcoms? Some do so because of the combination of their skill and star appeal; some because of having the right look or attitude; and some because they simply seem the least worst option available for the character. Then there are those actors - just a few - who have managed to be picked for a part because of nothing more than sheer chutzpah. One such performer was a then-unknown would-be actor called Don Estelle.

Don Estelle was so desperate to get into a sitcom that he hit on a spectacularly audacious strategy to realise his aim. He decided to lie.

Born in Manchester with the real name of Ronnie Edwards, Estelle, with his diminutive (4ft 9in) stature, stout frame, shiny face, high-pitched voice and nervous blink, was an unlikely candidate for a role in any television programme - let alone a sitcom. A hard-working 'wholesale only' soft furnishings salesman by day who sang part-time by night on the north of England 'pie and peas' club circuit, he somehow convinced himself that he not only could but also should become a professional performer on television.

Inspired by the sight of a ladies' fashion shop in Levenshulme called 'Estelle Modes', and by a co-worker who advised him that 'Don' sounded better than 'Ron', he changed his name to Don Estelle and began to find work as an extra on the many shows made at Granada studios in Manchester. Coronation Street was soon one of his semi-regular gigs, playing darts in the Rovers Return, hovering silently in the background in the corner shop, and walking up and down on the famous cobblestone street.

Distracted by this and his singing activities, he started neglecting his carpet sales, and was eventually sacked from soft furnishings. Now in urgent need of cash, he was soon reduced to taking a job delivering leaflets in Accrington and its surrounding areas.

Such a downturn in fortune might have left many a budding performer broken and bitter, but not Don Estelle. In fact, the ostensibly bleak change in circumstances actually seemed to liberate him, making him all the more determined to devote himself to the realisation of his show business dream.

Gone was the soberly-dressed seller of curtains, rugs and mats, and in his place came a long-haired, wide-lapelled, bell-bottomed bohemian. 'I drank a lot in those days,' he would recall, 'had a moustache, wore a medallion around my neck, I was crazy, romantic'. Succumbing to the temptation to 'freak out a little when the mood took you,' he felt he was preparing for those heady days and nights that stardom would render as regular.

Nothing of any consequence happened, however, until one day in 1967 when he bumped into the actor Arthur Lowe, who was in Manchester at the time working on the ITV sitcom Turn Out The Lights (a spin-off of a spin-off of Coronation Street). Estelle, even though he only had time to shake the great man's hand before watching him walk off towards the set, somehow convinced himself that he now had the legitimate and meaningful show business contact for which he had long been craving.

He thus went ahead and 'embellished' their brief encounter in numerous letters soliciting work, and sent them out to a wide variety of producers, writers and directors scattered across the nation. It might just be a matter of weeks, he reasoned, until he could leave Accrington and its leaflets far behind as he answered the call to head for the bright lights of London.

For the next twelve months, however, all that he elicited from these exertions was a succession of curt rejections, and it was looking as though the ruse was never going to work. Then, in the summer of 1968, some better luck struck: Arthur Lowe, following a spell spent mainly on the stage, reappeared on the screen as Captain Mainwaring in the new BBC sitcom Dad's Army, and Estelle's sagging spirits suddenly soared. This, he felt, was his chance - possibly his last chance - and he was determined not to let it slip away.

He thus proceeded to write a letter to the show's writer/producer David Croft, which he sent early on in 1969, depicting himself as one of Lowe's oldest and closest friends, and claimed that he was now belatedly taking his advice to ask to be considered for any kind of role in a TV sitcom. Dad's Army, he suggested boldly, might benefit from his particular talents.

Croft, who was always on the look-out for interesting new character actors for his unofficial television repertory company, was intrigued. Unable to double-check the details with Lowe himself, who was currently away on vacation, he responded by inviting Estelle down to London for an informal interview. When he first laid eyes on this odd-looking figure, however, he was more than somewhat bemused.

Estelle, his eyes magnified madly by his bottle-top glasses, had a stiff-shouldered posture that suggested the coat-hanger had been left inside his jacket, and a slightly backwards-angled, straight-kneed and flat-footed gait that resembled someone being brusquely frogmarched from out of a night club. Croft watched with a mixture of bafflement and amusement as Estelle read some dialogue in his helium-voiced, metallic and fitful northern accent, sounding more like a restless trade unionist dictating a postcard from Blackpool than a character stuck in war-time Walmington-on-Sea.

After some reflection, however, Croft resisted the temptation to tell Estelle to go back to selling shagpiles. He decided instead that there might be some laughs to be had from the sight of this strange little man in the odd fleeting scene, and so, after ordering him to get his hair cut, Croft booked him, as an experiment, for a brief role as a tiny but tetchy Pickfords removals man in an episode called Big Guns (Series 3, Episode 7).

It was not an auspicious start: Estelle, with his twitchy, jerky, awkward manner, repeatedly putting his hands in and out of his pockets and fidgeting with his cap, had all the acting sophistication of a robotic munchkin, and needed an unusually alert John Le Mesurier to deftly move a prop to prevent him from knocking it over with his clipboard. It was, however, quite funny in an eccentric 'so bad it's good' sort of way, and Croft was pleased enough with the performance to seek out Arthur Lowe after filming was over to thank him for recommending his great friend.

It was here that the ruse was rumbled. The puzzled expression on Lowe's face told Croft all that he needed to know. 'Don Estelle had swum into my ken by claiming to be a very good friend of Arthur Lowe,' the producer later explained. 'In fact he had met Arthur once for about 15 seconds, and Arthur wasn't sure he even knew him as well as that.'

Croft, though initially angry at the deception and tempted to banish Estelle from all future productions, soon came to find the incident rather amusing, and could only admire the novice actor's sheer nerve in tricking his way into contention for a part. The producer would actually use him again in the show, in three similarly brief and jerky appearances, as Gerald, one of Hodges' ARP warden sidekicks, and, although his acting, and delivery of lines, remained distractingly erratic, Croft, along with his co-writer Jimmy Perry, saw enough potential to develop a new character for him in the next sitcom that they were planning.

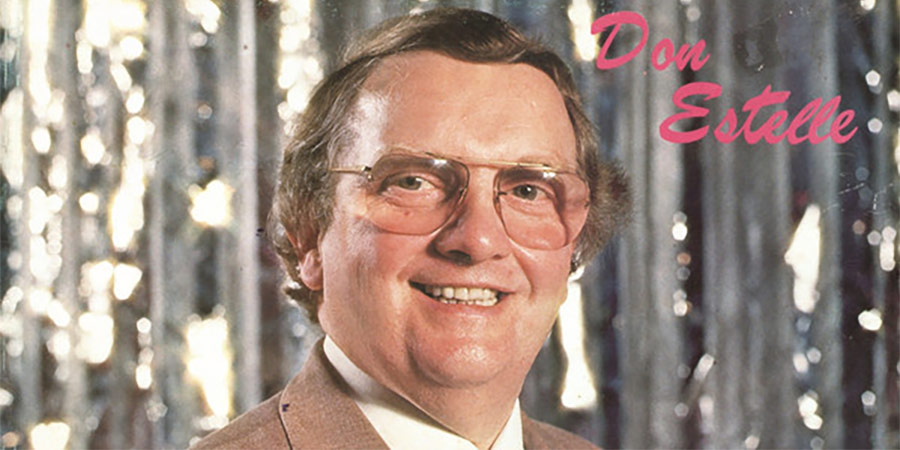

Sure enough, when they came to cast It Ain't Half Hot Mum late in 1973, Don Estelle's past deviousness was rewarded with his own central and bespoke role: Gunner 'Lofty' Sugden - a short, round, bespectacled, pith-helmeted character ('Is it a mushroom?' asks his sergeant major rhetorically. 'No. Is it a soldier? No. It's Gunner Sugden!') who possesses an improbably impressive tenor singing voice. It was the perfect part for him, and, as the show progressed, he found himself not only increasingly famous as a sitcom star but also, thanks to his two spin-off albums (the imaginatively-titled Sing Lofty and Lofty Sings) and novelty number one hit single, Whispering Grass, as a recording artiste.

Estelle, during that first flush of improbable fame, could hardly believe his luck. There he was, one of the stars of a BBC sitcom that was attracting audiences of up to 17 million viewers, as well as sharing the spotlight on multiple editions of Top of the Pops with the likes of Paul McCartney and Wings, the Bay City Rollers, 10cc, Art Garfunkel, Barry White and Eric Clapton, and making lucrative personal appearances all over the country, often in the company of his co-star and musical sidekick, Windsor Davies. It was all that he had dreamed of, and much, much more, and he revelled in it. 'I felt,' he said, 'on top of the world.'

Then, after seven years and eight series, It Ain't Half Hot Mum came to a close, and, almost as abruptly as it had begun, Don Estelle's stardom was practically over ('Working in TV is like a public toilet,' he would later reflect ruefully. 'Nobody is there long enough to make it their own'). Without any new offers of roles specially written to suit a short, squinting man who struggled to act but who could sing when circumstances warranted it, Don Estelle was trapped in the guise of Gunner Sugden, a character left stranded by his own departed sitcom.

Clinging to the wreckage, he stayed on the screen for a while, popping up every now and again for one-off bookings - usually still dressed as Lofty - in nostalgia shows such as The Good Old Days, panel programmes such as Through The Keyhole, and daytime chat shows like Pebble Mill At One, and he made a few more appearances on the club circuit sometimes as a solo singing act and sometimes, back in costume yet again, with the much busier Windsor Davies (who had already slipped swiftly into another sitcom, Never The Twain), but by the end of the 1980s the work was drying up fast and he had more or less faded from view.

He remained in denial for a while. He kept on with the pantomimes, even though the status of the location declined, and the size of the budget shrank. He also continued with the club act, although the audiences dwindled and the supporting band went from a full-on ensemble to a drummer and an electric organist.

Nothing cheered him up during this barren time. He would accept the odd club engagement, only to complain that it had given him 'flu-like' symptoms that led to him staying in bed. He went on vacation to Italy, only to return in a miserable mood ('I certainly wouldn't go there again with a tour operator'). He did a few more commercials, but hated the fact that they took so long to film, relied on his 'Lofty' look, and paid less than he felt was his worth.

A friend of a friend managed to arrange a few low-key tours of New Zealand, which he enjoyed, and a newly-installed home studio enabled him to keep recording his music, which brought him a certain amount of comfort, but, even then, nothing could compensate for the feeling that he was fast being forgotten.

Had he been a star of any other Croft and Perry sitcom, his face would have remained firmly familiar thanks to the regular repeats on the BBC, but, much to his anger and frustration, the inconvenient historical accuracy of It Ain't Half Hot Mum (along with one or two of its more dubious characterisations) was deemed too offensive in the current climate of political correctness, and so it, along with the image of Don Estelle, was kept hidden away in the archives.

He did his best to protest. He attracted the attention of the national press by complaining about the treatment of the show and himself, arguing that a 'militant minority' had scared mainstream TV executives into shunning the sitcom. His potentially incendiary comments, however, failed to fire-up any significant debate, and, to add insult to injury, The Stage newspaper introduced its brief coverage of the topic by describing him as a 'forgotten comic actor'. That cruel and brusque dismissal, in such a normally supportive industry outlet, hit home hard.

There was one brief return to the small screen, in 1999, when Estelle made a couple of appearances in The League Of Gentlemen as Little Don, the keeper of the Roundabout Zoo, but it was very much a novelty role, and nothing more came of it other than the odd less-than-flattering 'where are they now?'-style newspaper article. Estelle, however, was still not prepared to go quietly into the night, and, in the same year, he self-published his autobiography, Sing Lofty: Thoughts Of A Gemini.

It was, for all the wrong reasons, an extraordinary show business memoir. Part personal reminiscence, part philosophical tract, part political manifesto, part socio-cultural cri de coeur and part 'mad as hell' revenge rampage, it read like Charles Pooter from Diary Of A Nobody crossed with Kurtz from Heart Of Darkness.

Riddled with errors (Frankie Howerd, apparently, 'was a depressant') and repetitions ('I may have mentioned this at some other place in this book') and riddles wrapped in mysteries inside enigmas (the veteran DJ Pete Murray, apparently, was 'like Wogan on radio,' even though Wogan himself, quite famously, had been and still was Wogan on radio), it was also possessed during some passages by a kind of madly whimsical prolixity (his feeling of mild good fortune, for example, was expressed thus: 'I have, I am sure, a Guardian Angel, maybe a lower level Angel, in the heavenly firmament, because I am not good enough to get special dispensation of incredible things, with the higher up Angels, who glow better'). In spite of such problems with the prose, however, the book, in its own peculiar way, proved strangely, and sometimes unnervingly, mesmerising.

There was not much about his early life, given that his memories, he said, were now merely at the status of 'dim shadows of the subconscious'. He did, however, manage to resurrect one or two of some rambling and clichéd-stained stories about his early life, which contained such tired insights as: 'Life was hard for the working classes,' and 'many people lived by their wits'.

References to It Ain't Half Hot Mum, rather surprisingly, tended to be brushed aside in the manner of a memoirist far too eager to move on to more exciting topics, even though those supposedly more exciting topics turned out to be, to put it generously, at best only quirkily bland: 'Colin Meredith, who phoned me, had been invited to produce the Old Time Music Hall Centenary Tribute to Gracie Fields [...]. He invited me to make a contribution and I accepted right away. [But] there was a problem - on the same day I was booked at the Spalding Flower Festival...'. Similarly, the couple of months that he spent working on the same set as Dudley Moore and a host of other Hollywood stars in Santa Claus: The Movie only merited two scrupulously anecdote-free sentences, whereas the invitation that he received 'to inaugurate a steam engine on a private railway' is commemorated in the larger space of a page.

There were also, by way of some tantalising tales of private travails, a few enigmatic allusions to tensions in a succession of local neighbourhoods ('We had a lot of trouble in Buckingham, which I don't want to repeat, but our survival was at risk'); a very brief and elliptical account of the breakdown of his first marriage ('It was about the time speed king Donald Campbell was killed in Bluebird, his powerful craft, in the Lake District, in early January 1967'); and the odd tale about his exciting trips abroad (such as the time in Moscow when, after being distracted by 'the most beautiful pair of "boobies",' he 'fell down a hole, landing on top of my Pentax zoom camera, which I love, and broke it').

There were also innumerable paeans of praise celebrating, of all places, the town of Rochdale (a location, he insisted improbably, that is 'the most convenient place to be in the country'), inhabited by people who are 'warm and friendly' and the 'salt of the earth,' and whose town hall, he argued repeatedly, 'is one of the best looking in the country'). Indeed, so obsessive were the pro-Rochdale riffs that additional travel advice was provided in case any readers from abroad might stumble onto the approbation and feel compelled to visit this magical-sounding place.

There were, in addition, however, some quite alarmingly angry diatribes about all kinds of unexpected subjects.

There was, for example, a positively Rousseau-esque rant about the creeping pressures of social conformity, with him complaining about 'all the duplicated clones who walk about, looking like one another, self-assertive, confident, unsmiling, saying, "Look at my even larger CV, and ego, coming out of my head". Head is the wrong word of course, but I am sure you know what I mean'.

Then there was a short, sharp and sobering reflection on relativism: 'We all live within ourselves on an island alone. As an example, if you asked someone, "Did you enjoy that?" and they said "Yes, it was alright" in a rather unimpressed way, you may then think, "But I thought it was fantastic". End of example.'

There was also a passionately strange critique of devolution ('It's a complete disaster. You have got to laugh, but it's not laughable when you think about those millions of deaths to defend freedom!'); an emotional but ultimately unresolved meditation about the insanity of war ('Sometimes I ask myself how could God condone killing other people by bombs or in hand to hand fighting, when in peace time you might be having a drink with them or visiting their country for a holiday') as well as the dangers of a repetitive apocalypse ('Mankind can eliminate everything, if he so wishes, and sometimes he does'); and a stream of invective about the essential unfairness of modern life ('You work all your life and never achieve anything, or you're very successful, by working very hard, but some congenital idiot can pick six numbers in the Lottery, in Great Britain, and walk away with six million pounds'). There was even a concise little lament about the cruel transience of life ('It's as if you're on an express train, which of course you are - a Time Train!').

Estelle reserved most of his venom, however, for biting the hands of the show business bosses who had stopped feeding him. Raging at 'the tight crutched morons in white pants called producers' (who 'know as much about entertainment, and what the public like, as a visiting Martian'), he denounced them all for encouraging the kind of comedy that revolved around 'suggestive sex garbage, which reflects their stinking minds,' and music that catered only to 'bestial, basic, sex mad, drunken louts with an IQ of morons'.

He was equally scathing about chat shows, claiming that they had been reduced to serving as a showcase for hosts and guests alike to stage 'a self-ego debate, a grand display of their psychic peacock feathers, and lastly a total insincerity in replies which are as dead as the film stock used before it was wasted on a patronising performance'.

As for his successors as so-called popular entertainers, Estelle made it clear that he was most definitely not a fan. He reflected bitterly if bizarrely that most of them 'sound as if they are swinging from their genitals, if they have any sex gender at all'.

It came as no great surprise, therefore, after airing such blisteringly bitter views, that his current conception of the human condition was rather bleak. 'We are,' he lamented portentously, 'just so much mashed potato.'

Perhaps the most unintentionally revealing observation made in the whole of this mind-boggling memoir came when Estelle, drawing somewhat unsurely from his rag-bag repository of received wisdom ('It is, I believe, an Arabic saying'), remarked: 'As they say, "You are what you are".' The poignancy of this opinion, in spite of its authorial intention, came from the fact that, at this late stage in his life, Don Estelle was not what he was, but what he had been: he was still Lofty, and he always would be.

Doughty and unbowed, however, Estelle vowed to carry on, and embarked on a self-organised promotional tour of provincial shopping centres, usually turning up unannounced, sometimes assisted by a lugubrious-looking friend in a flat cap. Dressed in his by-now yellowing and extremely well-worn 'Lofty' costume, complete with a hummus-hued pith helmet planted on his head, and dragging along a large suitcase, he would set up a trestle table, on to which he would place piles of copies of his book, along with old vinyl records, cassettes and CDs of his music, and then, with the accompaniment of backing tracks blaring from a portable boom box, he would sing an assortment of songs (such as Bright Eyes, I Just Called To Say I Love You and, of course, Whispering Grass) while shoppers wandered past on their way to Boots and Argos. To the few inquisitive individuals who stopped and loitered nearby, he would, in between songs, invite them to purchase any of his products, which he was always more than happy to sign for them.

Some found it a sad and pathetic sight, and some made that view known in print, but the truth was that Don Estelle, for better or for worse, was merely doing what he had been doing ever since he sat down, all those years ago, and wrote that letter to David Croft: drawing on a quite extraordinary degree of chutzpah, and a very thick skin, to do whatever he could to dream on.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more