Digs, dives and landladies: Comic travellers' tales

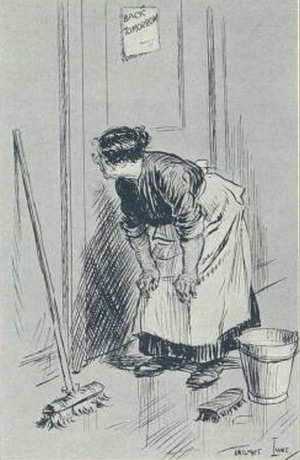

Among the most common subjects for actors deep in their anecdotage are the strange places where they've stayed as strolling players - and the even stranger people who've run them. Insalubrious boarding houses and idiosyncratic landladies were particularly popular topics for comic tale-telling throughout most of the twentieth century.

Not all of these places and patrons, of course, were considered poor by those who had cause to frequent them. There were many theatrical landladies - addressed, by tradition, via the endearing soubriquet of 'Ma' - who were treasured friends and allies within the show business profession.

These were nurturing figures who would greet the visiting entertainers warmly, see that they ate well, slept well and stayed positive regardless of the local reception, and put up with everything from misbehaving performing animals to the occasional late payment of bills.

They understood that they were not running normal guest houses, and were not dealing with normal guests. The best of them (some of whom were ex-entertainers themselves) were always ready to accommodate insecure, or arrogant, or exceptionally mercurial individuals who might rely on an excess of alcohol, or the provision of a particular food, or a context of constant chatter or constant quiet, to prepare for or recover from the various stresses and strains engendered by the effort to entertain an audience. It was partly down to such landladies that the stars and casts of the country's summer seasons and pantomimes, and all of the other provincial productions in between, would work as well as they usually did.

Mona Clark, for example, who presided over premises in Southsea, was a legendary surrogate mother among travelling entertainers. She was quite a glamorous woman - tall, slim, with her silver-white hair always worn up in a chignon - and she relished welcoming anyone who worked in the show business world. Accustomed to so many of such performers returning for one season after another, she knew exactly how Frankie Howerd preferred his eggs fried of a morning, how Jimmy Tarbuck liked his tea, how Tommy Cooper liked his Scotch after supper, and how the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company always wanted their rooms arranged. She was discreet, she was sympathetic and she was supportive. The stars loved her rooms, her food, and they loved her.

Then there was the small, dark and neat 'Auntie' Alma McKay ('I don't run digs - this is a registered hotel'), who for many years presided over a similarly packed-out premises - the 12-bedroom Astra House at number 11 Daisy Avenue in Manchester - at a time where there were no fewer than twenty-three variety theatres in the city. The all-round appeal of her accommodation, the quality of her cooking (four large meals every day) and the power of her personal charm served as a magnet for many of the top acts who visited from the 1940s through to the 1980s, including Laurel & Hardy, Max Miller, Gracie Fields, Flora Robson, Mae West, John Gielgud, Thora Hird, John Mills, Peter Sellers, Marlene Dietrich, Richard Burton, Roger Moore and Morecambe & Wise (more than twenty thousand artists in all) - making her one of the busiest and best-loved landladies in the business. 'Alma,' as Ernie Wise would say upon her death in 1995, 'was simply the best'.

It was no surprise, however, that, due to the sheer number of such establishments during the era of music hall and variety (when there would often be scores of them in towns and cities packed into the same bustling block of streets), the ones languishing down at the bottom of the barrel would vastly outnumber the ones floating right up among the crème de la crème.

The stories about the various inadequacies of many theatrical digs - and their owners - are legion. Researching the precise provenance of such anecdotes is a notoriously challenging task, given that, once told, they have been 'borrowed', embellished and re-told by countless other performers, but the essential substance of each story is always revealing.

The Scottish comedian Chic Murray, for example, recalled one set of digs with particularly poor facilities: 'The landlady said, "Do you have a good memory for faces?" I said, "Yes. Why?" She said, "There's no mirror in the bathroom"'. Tommy Handley had a similar anecdote about being trapped in the lavatory of a Blackpool boarding house yanking a chain that repeatedly failed to flush: the landlady eventually banged on the door and shouted the vital instruction: 'Mr 'Andley - you have to surprise it'.

Some lodgings were so primitive and chaotic that any performers coming back tired and emotional after their final show of the night would then have to navigate their way through the shadows via odd little handwritten signs to reach wherever they needed to be. One such scrawled note announced, 'The gas is turned off at the meter at midnight and I don't provide no candles', while another had the warning: 'Professionals is asked not to do their washing in the bath as it stops up the drains', and a third, pinned to the kitchen door, declared: 'I don't cook no hot dinners'. If the guest managed to make it all the way to the back of the establishment, he would have found a fourth sign that said: 'As there is no light in the lavatory at the bottom of the garden, a torch has been provided. Be sure it's the near door on the right - the other belongs to next door and we're not speaking'.

Then there were the unpredictable disruptions to be caused by some of the 'speciality acts' who were currently sharing the premises. One entertainer of a rather delicate temperament was tormented during the night by the relentless racket of groans, grunts, bangs and crashes coming from the other side of his wall. Summoning the landlady to complain, she rested her hands on her hips and said matter-of-factly, 'Don't worry, dear, it's only Max and Moritz'.

'Are they acrobats?' the still-anxious man inquired. 'Nah, they ain't acrobats,' came the reply. 'They're gorillas. They're just amusing themselves by rocking about in their cages. I have 'em every year and they go round the circuit'.

Sometimes, conversely, it was the innocent incumbent who was made to feel like a problem. One host was so protective of the solitary communal lavatory that she would do her best to discourage any guest from ever using it, patrolling the area outside like a soldier guarding a palace. Knocking loudly on the door when one of them managed to evade her, she shouted: 'What are you doing in there?' The comedian inside shouted back: 'I'll give you two guesses!'

The actor Bernard Miles would recall the night when he was just about to put his head down on the pillow when the hair-netted landlady popped her head around the door and urged him not to put the chamber pot back under the bed if he used it during the night. The reason she gave was that 'the steam will rise and rust the bed springs'.

Then there was the food ('You've got two choices,' the saying went. 'Take it or leave it'). Many landladies, due to a mixture of parsimony and personal prejudice, offered only a very limited and depressingly repetitive menu for the week. The great northern comic Robb Wilton, when staying in digs at Bolton, had to put up with nothing but tiny portions of unrecognisable fish for four days in succession. When his landlady tried to cheer him up by reading his tea leaves and declaring that he would 'soon be meeting a stranger', he replied with his trademark sigh, 'I hope to God it's the bloody butcher!'.

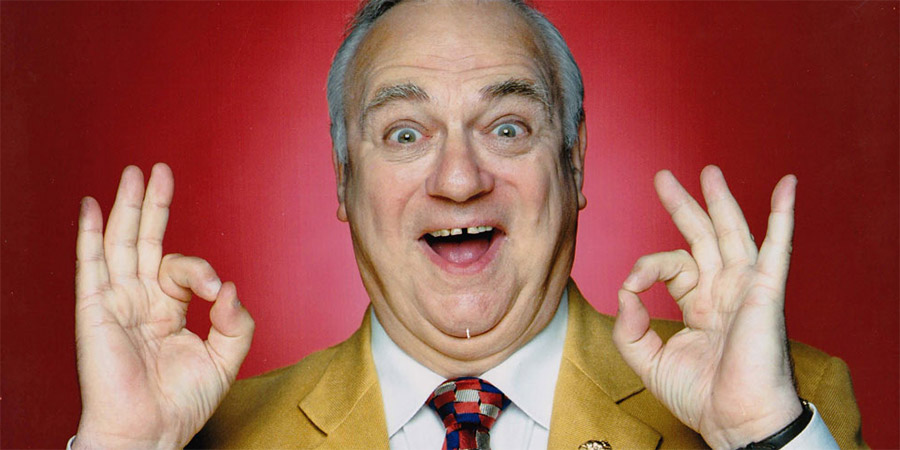

Roy Hudd, when appearing in a pantomime at the New Theatre in Oxford, stayed at digs nearby in which the landlady, cigarette always dangling out of the corner of her frowning mouth, served him a small plate of baked beans every single night for supper. Returning on Christmas Eve after yet another long day of rehearsals, he slumped into his chair at the dinner table and muttered to a fellow guest, 'If it's baked beans again tonight I'll bleeding throttle her!'.

It was indeed baked beans again. As he stared at the soft and squidgy orange mass, however, he spotted something extra buried beneath the beans at the centre: a very small, wrinkled and pale-looking cocktail sausage.

Infuriated, he got up, went out the door and shouted sarcastically down the corridor: 'Oi, Ma! I think you've made a mistake - I've found a sausage in my baked beans!'

'I know,' she said, sticking her sad-looking face out from the kitchen door. 'Merry Christmas'.

Sausages, curiously enough, had been the source of clashes between landladies and their guests for a very long time. Back in 1906, the musical comedy artiste J.L. Shine wrote a passionate if prolix letter to a newspaper recounting his own banger-related battle.

'I remember in my very early days,' he noted, 'taking home one afternoon some sausages to be cooked for the breakfast of self and another young actor, with whom, for sweet economy's sake, I shared rooms. There were eight succulent rolls in the parcel which I delivered to the landlady, and to my indignant surprise only six reposed upon the dish in the morning. "Ma" was rung for, and asked for an explanation. That heroic woman looked me straight in the eye and calmly said, "Well, you see, sausages do shrink so in cooking"'.

The Scottish singer and comic Sir Harry Lauder sought out sausages as a means of escaping from small and rubbery pork chops, which his landlady had been serving him for every single meal. She protested, upon being presented with them, that she didn't know how to cook sausages.

Sir Harry patiently explained that they should be cooked 'like fish'. An hour later she brought them in, 'cleaned' with the skins on the side, poached in milk.

Quite a few other landladies, it seems, were similarly unworldly in their culinary ways. The stage actor Adrianne Allen, when she was staying in Southsea, dropped in her bag of shopping one morning - various comestibles along with a loofah for her daily ablutions - and asked her landlady to cook her lunch whilst she worked in her room on her script. The meal she was subsequently served was the loofah, boiled and sliced up into bite-sized chunks, covered in a parsley sauce.

The popular band leader Jack Hylton experienced a similar epicurean shock when he bought some cucumbers for his landlady to serve for his supper. He was far from impressed when she ended up boiling them. The following week, in another town and another guest house, he brought in another bag of cucumbers, and told his new landlady what the old one had done. 'My goodness me, Mr Hylton,' she exclaimed. 'What a silly fool. Didn't she know they need to be baked?'.

Ronnie Barker faced the same type of dining deflation when he was in digs during his time as a young repertory actor in Rhyl. Bored by the blandness of his daily dishes, he decided to put his hand deeper into his pocket and treat himself to eight ounces of the best fillet steak that the local butcher could provide, along with a punnet of fresh asparagus, and presented them to his landlady to prepare for his next dinner.

The cutlery-clenching sense of keen anticipation was acute when the time came for the meal to finally be served later that evening. 'There you are, dear, I bet you're hungry,' said the smiling landlady as she carried it all in. 'I've made your meat into a lovely stew, and put your bluebells in water'.

A far worse food-related experience was had by the two music hall stars Dan Leno and Vesta Tilley, who were sharing a guest house in Manchester over the festive period during the 1890s. As both of them were accompanied by their respective young families, they were looking forward to sharing the Christmas Day feast they had arranged to be cooked by the landlady.

The meal was due to be laid on the table by six o'clock, sharp, so that all the performers could return to the theatre for the third and last show of the night. When, however, they gathered expectantly for the turkey, trimmings and plum pudding, they found that the landlady and her husband, having been drinking for most of the day, had dozed off alongside their dog and completely forgotten to put the large dinner in the oven. The combined Leno and Tilley families' Christmas feast, therefore, ended up as tea and boiled eggs.

Going back even further into the Victorian era, another bone of contention concerned those landladies who (more than a century before Rick Stein started getting stick for the price of his pots of tartar sauce) included in the bill a separate charge for 'cruet' - salt, pepper and any other condiments on offer with the meals. Visiting entertainers became so enraged at this unexpected addition (often as much as eighteen pence - roughly eight pounds in today's money) that they started attempting to take the half-full glass cruet containers with them on the grounds that 'I have bought and paid for it!'

In addition to the food itself, there could also be issues relating to the often somewhat cramped communal room in which it was consumed. 'The soup sounds good,' observed W.C. Fields with a wince (in The Old Fashioned Way) as his weary vaudeville traveller, The Great McGonigle, arrives to much slurping from his fellow diners. Aside from such niggling noises, many an entertainer would also complain about the near-ubiquitous home-bred cats and dogs that competed for their chairs and chops, and the uncaged pet birds that fluttered hither and thither, as well as the interventions of the various performing animals that were also, in some establishments, allowed at or under the table.

Sometimes the root of the problem was neither the rooms nor the food but simply the behaviour of the landlady herself. One of the most infamously eccentric of these was encountered by the comic actor Arthur Lane. He was getting ready for a midweek performance in a small provincial town when he realised he'd left one of his props back in his lodgings. Racing off in the early afternoon to retrieve it, he let himself in quietly via the back door only to stop in shock at the sight of his landlady lying naked on the kitchen table with a very pink milkman on top. Unsure of how to react, he nodded, hurriedly stuttered a studiously formal 'Good afternoon', and then ran up to his room for the prop.

When he returned after the last show later that evening, the landlady brought him his supper and said with a simpering smile, 'I do apologise for this afternoon, Mr Lane. You must think me a terrible flirt!'.

The actor John Blythe encountered a similar but rather more 'up front' landlady when he booked into a boarding house in Bath. 'Are you the sort,' she asked him, 'to entertain the opposite sex in your room at night, play music and drink into the early hours?' He assured her he was not. 'Well, I am,' she said, 'so I hope you're a heavy sleeper!'.

Whatever the crisis, however, they would always stick rigidly to their own rules. During the First World War, for example, one landlady in Great Yarmouth, well-used to welcoming exotically-named novelty acts from the continent, was shaken one evening when a policeman burst in, shouting: 'The Zeppelins are coming!' Her defiant reply was: 'Oh, no, they're not - they ain't booked 'ere, so they ain't coming 'ere!'.

Another host had a strict status-specific ritual for addressing her guests. If it was a star of a show, she would put her teeth in; if it was a mere supporting player, she would leave them out.

Some landladies would cause trouble by offering reviews as well as room and board. By convention, they were always given complimentary tickets to the first performance on a Monday; if they went and enjoyed their new guest's act, they would often fuss over them for the whole of that week, but if they did not approve, the visitor would be made to suffer for the rest of their stay.

Harry Secombe, touring the halls soon after the Second World War with a somewhat limited 'man having a shave' routine, was the shaken recipient of such an unsolicited critique. 'One old dear,' he recalled, 'would thump my meal on the table in front of me, sniff loudly and walk out of the room mumbling, "Call yourself a comic?"'.

Another performer, the grandly dramatic actor Donald Wolfit, made the additional mistake, after inviting his landlady to see him perform, of then complaining about her cooking. Holding up an unappetising-looking piece of meat, he asked: 'Is this ham?' - to which she replied tartly: 'At which end of the fork?'.

The comedian Ronald Frankau brought that kind of brusqueness on to himself when he was heard by his landlady joking on stage that 'theatrical lodgings are an occupational hazard'. His next night's supper was served in an atmosphere of icy silence, apart from the sound of the plate being slammed down in front of his face, until, as his host started to go out of the door, she paused, turned back, stared straight at him, and said: 'So are the pro's, Mr Frankau, so are the pro's!'.

When it came to the parting of the ways, the sorrow, for one or other party, sometimes lacked its proverbial sweetness. This was the moment when it really could get rather ugly.

There were a number of ways to leave less than favourable reviews in those ancient days before the arrival of TripAdvisor. Most landladies had a 'testimonial book' for contented customers to leave their comments, and some performers used a code to register their real displeasure: if ever the words 'Quoth the Raven' appeared in those pages (which was a reference to the Edgar Allan Poe line 'Quoth the Raven "Nevermore"') it was a warning to others that those digs were to be avoided.

At a later stage in show business history, Morecambe & Wise, sensing that such a conceit was in need of updating, were among those who favoured another style of ciphered censure. They would write, when a place or patron had displeased them: 'We will certainly tell our friends!'.

One tried and tested act of revenge if one's stay had been especially unpleasant was to tack a kipper under the dining room table shortly before departing. This was based on the premise that, as it was deemed to be the last place that the landlady was likely to search for the source of the offending smell, the stench would be left to linger longer than most of the current inhabitants could stand.

An alternative strategy was employed by that most elaborate of practical jokers, the comedian 'Monsewer' Eddie Gray. When he found a guest house wanting, he would recommend it to those performers he felt needed some punishment themselves, telling them: 'The woman who runs it is a charming lady, but she can hardly hear a word you say, so - don't be shy - you'll have to really shout'. The landlady in question would then have to deal with a succession of new visitors who would immediately start screaming at her as soon as she opened her door, rattling her eardrums until she finally shouted back: 'I'm not bloody DEAF, you know!!!'.

Not all of such parting shots were fully deserved, however, and some could backfire badly on those who perpetrated them. A salutary example (sometimes attributed wrongly to Arthur Askey amongst others) was the experience, during the early 1930s, of the comedian and singer Bobbie Comber.

Comber - a chubby-looking 'cheerer-upper' - was touring the country at the time, alongside Claude Hulbert, Paul England and Eddie Childs, as part of a popular musical-comedy quartet known collectively as Those Four Chaps. Usually, because they could pool their resources (and were earning a fair amount extra from their regular radio appearances), they preferred to rent their own cottage rather than run the well-known risks with an unknown landlady, but when they did gamble on a guest house they ended up regretting it greatly.

They booked into digs in Leeds for a week's engagement at one of the local theatres, and brought with them a large bottle of sherry, which they kept on Comber's bedroom sideboard. The plan was that, each evening, they would unwind with a glass before going downstairs for their supper.

The first night, however, they returned to Comber's room after the final show and found that the bottle had already been opened and a drop had disappeared. The other three, initially, suspected that Comber must have snatched a quick snifter all on his own, but then realised that, as he had been out with them all day, it must have been someone else.

The second day, they came back as usual, Comber reached for the bottle, and noticed that the level of the sherry had dropped even further. Seething at the thought that their landlady - as the only other person with access - was slipping into his room while he was out and slurping the spirits, Comber and his three colleagues agreed that, from this point on, he should retaliate in a similarly stealthy fashion.

Transferring most of the surviving sherry to another bottle, which Comber hid inside his suitcase, he proceeded to top-up what was left by peeing into the original bottle and then placing it back on the sideboard. That, they all agreed, was the right way to punish such pilfering.

The following day, however, Comber was surprised to find that the level of the bottle on the sideboard was now getting lower at an even faster pace than before. 'She's been at it again!' he exclaimed to his colleagues. It continued to happen all the way through to the Saturday.

Finally, once their run in the town was over, the four men were paying the landlady their collective bill when Comber could not resist saying as a passing shot: 'Well, thank you, Ma, for the week - and I do hope you enjoyed the sherry'.

The landlady replied to this by smiling sweetly and saying: 'Ooh, well, I do hope you didn't mind me keep taking a little bit of it, Mr Comber, but I saw that all of you gentlemen liked it, so I put a drop in your trifles every night'.

Such attempts to inflict retribution, however, were not always one-way, and sometimes the landladies (whom Derek Nimmo would divide into 'the ones who begin by calling you "dearie" and end up calling you "young man", and the ones who begin by calling you "young man" and end up calling you "dearie"') would exact their own revenge upon a guest whom they had come, for some or other reason, to strongly resent. Probably the cruellest of such reprisals concerned the fate of poor Arthur the parrot.

In 1979, the club performer George Birch booked in for a week at Miss Ida Rubell's theatrical guest house in (yes, that place again) Leeds. He was accompanied by a diminutive fellow artiste named Arthur.

Arthur the parrot was George's pride and joy. 'Arthur was no ordinary performer,' he would later explain. 'He spoke three languages, ate scrambled eggs, and had a small but varied repertoire of nineteenth-century love songs'.

This was no idle boast. Arthur was known in particular, for better or worse, for being able to screech through at least one verse of Seeing Nellie Home while perched on George's left shoulder and flapping his feathers for effect.

The irascible Miss Rubell regarded George as a model visitor, but took an immediate and intense dislike to his small and squawking colleague. One evening, a few days into the stay, Arthur went missing before dinner, leaving George in a state of immense distress.

A search was duly conducted, but without any bird being found. The other diners thus sat down again and finished their meals, shrugged their shoulders and went off to their rooms.

It turned out, after a subsequent police investigation, that Miss Rubell, in a spiteful and premeditated act that surely ought to have been kept confined to a Hitchcock screenplay, had not only abducted and done away with Arthur but had then plucked him, cooked him, and served him up for dinner with a portion of rice as the chalk-boarded dish of the day.

'Mr Birch was an excellent guest', the blank-faced and unrepentant landlady would go on to say during her eventual trial in the local crown court. 'But I couldn't take the parrot. It waddled round the hall asking for its bill and complaining about the service. It was me or the parrot'.

Miss Rubell was bound over to keep the peace. The devastated Mr Birch, meanwhile, though reimbursed, was left with no parrot and no act.

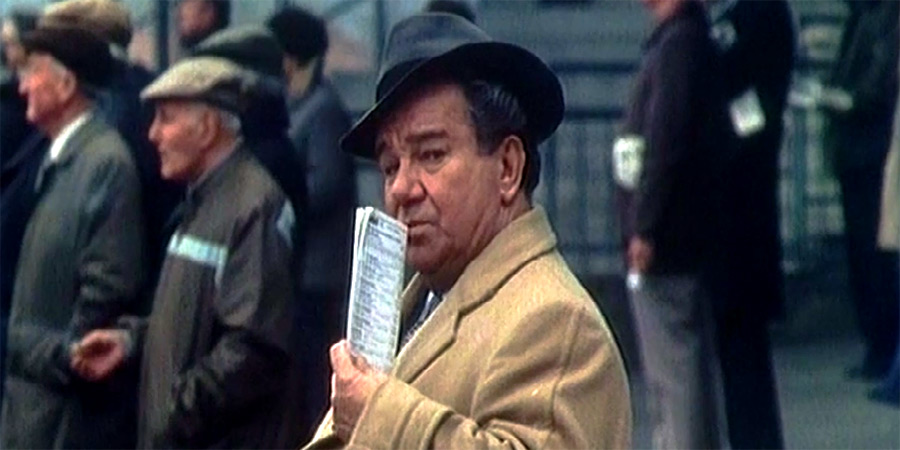

In addition to such bitter battles between the owners and their paying guests were the occasional crises that were caused by the visitors who were either cynically disinclined, or desperately unable, to pay their way. With periods of poverty being a sad fact of life for many performers in such a chronically precarious profession, there was often the possibility that, in spite of the best of intentions, the visitor who arrived full of hope might have to leave prematurely with their pockets now empty.

This was the dubious tradition termed 'scarpering the letti'. This referred to such unfortunate souls as those who, if they had been relying on a share of the box office takings and the business that week had been poor, were left unable to pay the bill ('nanty dinarly,' as they might have put it in showbiz slang) and thus felt obliged to do a midnight flit.

Sometimes, if they could climb out of a window and down a drainpipe, or sneak downstairs without the staircase creaking, or even arrange for a friend to carry them out curled up inside their own travel trunk, this would work. Many other times, however, if most definitely did not.

Certain landladies, for example, had come to master the jargon, so whenever they overheard, say, a downbeat troupe of acrobats whispering to each other over the breakfast table that they would have to get ready to 'scarper the letti,' she would let them know they'd been rumbled by warning them that, if they made such an attempt, they were guaranteed to 'get a ferricadouzer when the carsa-homey finds you!' (in plain English: they would be badly beaten once she caught up with them).

Then there were the landladies who were quick to figure out the tricks. Those who ran guest houses at the seaside, for example, would not fall more than once for the ruse that saw an impoverished boarder sneak all of his belongings out the back door to his waiting accomplice and then stroll out the front wearing only his underpants, announcing that he was 'just going for a swim'.

One performer who later admitted to his own involvement in this sort of devious activity was the tall and toothy comic actor Cardew 'The Cad' Robinson. Young and new to the business, he was appearing at the Swansea Empire as part of a knockabout troupe called The Crazy College Boys. The act consisted of one middle-aged man (their boss, Joe Boganny), three teenagers, one dog and a couple of dwarfs, and, operating on a miniscule budget, they all had to cram into the same room in digs.

Robinson was woken abruptly very early one morning to be informed by Boganny that everyone would have to 'scarper'. This involved the two dwarfs and the dog descending to the kitchen via a serving hatch, exiting through the back door cat flap, and then waiting outside for the others to climb down in a precarious fashion from the first-floor bathroom window.

A bleary-eyed Robinson found himself having to repeat this mode of escape more than once as the tour continued. 'Two weeks in show business', he later reflected, 'and I'm a crook already!'.

The case of the music hall comedian Harry Tate served as a sobering lesson for all those entertainers who considered taking on their landladies in a court of law. It taught them that, as a local landlady tended to maintain close ties with the local authorities, any hearing of a disagreement between guest and host was likely to be skewed in the latter's favour.

Tate's former landlady, a Leeds resident named Rachael Davis, took him to court in 1903. The previous December, Tate had booked a couple of rooms for a five-week engagement in a local pantomime, with the option of extending his stay if the show proved a big enough success. After just a fortnight, however, he angrily demanded the bill and, allegedly without any explanation, announced he was 'going to clear out of this' right then and there.

It was put to the landlady, amid much laughter in court, that, among Tate's own accusations, she had served him a rice pudding in a small tin bucket, after half of it had already been eaten by her family; she had responded to his order of sole for breakfast by bringing in a 'yard-and-a-quarter of cod' and telling him that she would warm it up for his dinner and serve it for supper, too; and he had resorted subsequently to buying all his meals in a nearby hotel. Tate also complained that the rooms had been drafty and cold, the furniture in a state of disrepair and a family of mice had been found living in the upright piano.

The judge, however, brushed such matters aside and ruled promptly in the landlady's favour, saying that there had been insufficient grounds for Tate's premature departure. Other disgruntled guests who were just passing through a town would think twice before daring to take on their well-connected host.

Most comedians, regardless of what they had endured, resisted the temptation to include their experiences of landladies and their digs even as merely a light-hearted part of their stage act, mainly because, unless they could afford never to darken such doors again, the likelihood of future retribution was far too high. An exception to the rule was the music hall comic George Robey, who toured for many years with a song, The Pro's Landlady, as one of his regular routines ('...In fact I have to live out in the suburbs/When I'm sure by now I should have been a star/And to have to serve up ham-an-eggs and haddocks/And to let those saucy actors call me Ma'). Generally, however, such teasing was still considered to be far too close to their temporary homes.

There would later be the odd attempt to capture some of this fast-crumbling context on the stage and screen. Robert Morley's affectionate 1937 play, Goodness, How Sad (adapted for the cinema in 1940 as Return To Yesterday), featured a company of actors in a seaside boarding house, but, aside from the odd moan about the hard beds and broken mirrors, the author avoided biting any hands that might yet feed him.

It was much the same on television. The double act of Elsie and Doris Waters agreed in 1959 to play a pair of theatrical landladies in an ITV sitcom, called Gert And Daisy, but the format soon flopped. Even though the basic idea had plenty of comic potential, several subsequent series, featuring different performers, met with a similar fate (including two more ITV sitcoms: the 1969 Thora Hird vehicle Ours Is A Nice House, which struggled on for thirteen episodes, and the other called Rep - shown in 1982 but set in 1948 - featuring Patsy Rowlands as Flossie Nightingale, which only lasted for four).

It might be time for another try. As a period piece, there would, after all, be a strong and characterful leading role for a woman, a colourful community for a supporting cast to explore, and, as the many anecdotes have survived to show, plenty of incidents to animate the action.

Such an elaborate and closely-knit milieu would seem intriguingly exotic now in this era of towering and impersonal Travelodges, isolated Airbnbs and interchangeable motorway service stations. Is the present arrangement necessarily better? It's probably nowhere near as bad as the worst, but nowhere near as good as the best, of the old days of cosily quaint camaraderie.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more