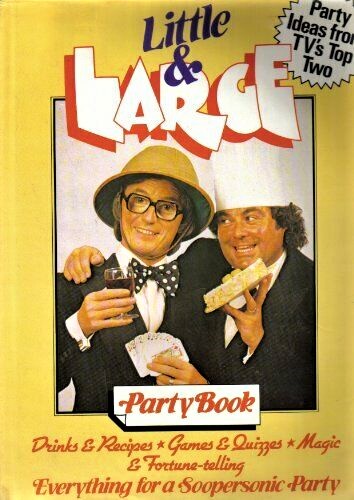

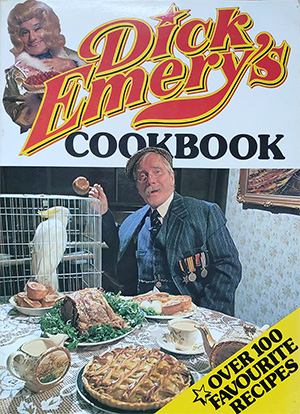

It seemed a good idea at the time #3: Dick Emery's Cookbook

When Dick Emery decided, in 1979, to write a comedy book, he was following in a relatively new but quite profitable tradition. When he decided to make that comedy book about cooking, he was following in a somewhat older, but still fairly profitable, tradition. The combination, in his eyes, no doubt made sense. The combination, in the eyes of his readers, made less sense.

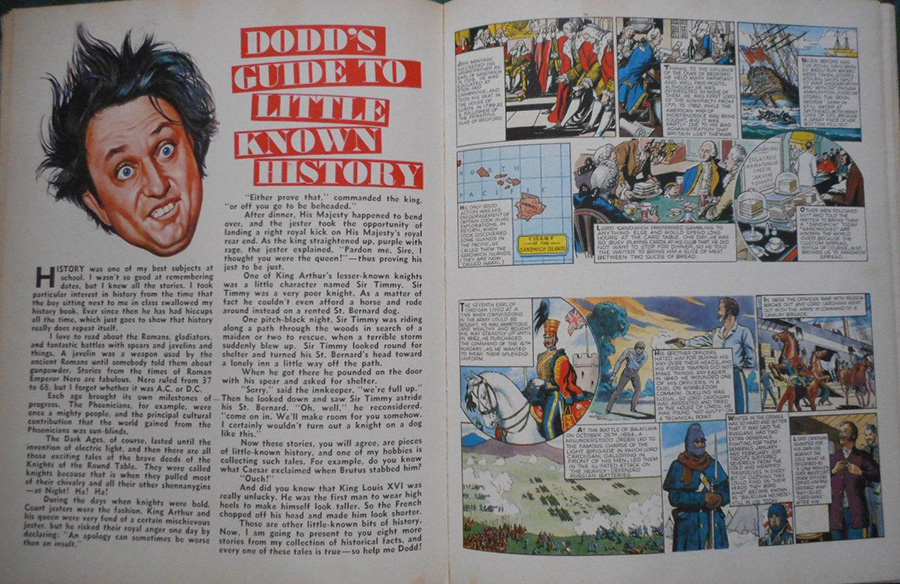

The trend for comedians to write comedy books had really taken root, in Britain, in the mid-1960s, when Ken Dodd published a tome entitled Ken Dodd's Big Doddy Book in 1966. Dodd was arguably the most successful comic in the country at that time: he had only recently broken box office records for his show at the London Palladium, the critics were queuing up to praise him, and even his musical recordings had risen to number one in the charts. A book, it was judged, was just one more practicable commercial venture.

Ken Dodd's Big Doddy Book was rather impressive in the sense that it was not some lazy cash-in, but actually seemed to have been put together with real effort, imagination and care. Aimed at children 'from six to a hundred-and-six', it contained plenty of pictures, jokes, stories, cartoons, puzzles, quizzes and art tasks.

It sold very well, won Dodd more young fans, and obviously planted a seed in the minds of other comedians and their managers, because it was not long before several of them were following in his footsteps. Out went, for a while, the straight and rather strained 'as told to' autobiographies and in came the joke books and activity annuals.

The 1970s became a golden era for the genre, as a new generation of comedians - many of whom were talented writers and artists themselves - seized on the opportunity to revise the format so that it appealed to older and more knowing fans as well as their younger followers. The success of Monty Python's Flying Circus, for example, would see the troupe publish not one but two richly inventive and very engaging volumes - Monty Python's Big Red Book (1971) and The Brand New Monty Python Bok (1973) - and these were followed by the similarly clever and playful contributions from The Goodies - The Goodies File (1974) and The Goodies Book Of Criminal Records (1975).

A huge influence on such later ventures as Viz, these books featured satirical takes on tabloid news stories and problem pages, picture strips and sports reports, readers' letters and classified ads, as well as parodies of vintage children's stories, and also such delightful oddities as 'Edward Woodward's Fish Page,' 'How to Take Your Appendix Out on the Piccadilly Line' and 'The London Casebook of Detective René Descartes'. In terms both of words and graphics, they were some of the most interesting, absorbing, lively and even inspiring comic products of the time.

Such publications showed how these kinds of books, rather than merely being 'fun' activity volumes for children or mildly diverting mementoes for adults, could genuinely be contexts for comedy in their own right, complementing, and in some cases extending, the kind of ideas and innovations that were starting to feature in some of the television shows of the time. At their best, they would serve as much as laboratories for the authors as they did entertainments for the readers.

Long before performers started channelling their comedy through books, however, they had also been strangely drawn to cookery. Ever since the end of rationing, comedians, for some peculiar reason, had been publishing recipes either in newspapers and magazines or books.

This was a far more mysterious phenomenon. While it is understandable why people might assume that if someone can make you laugh in person they can probably also make you laugh in print, it is far harder to comprehend why people might also assume that if someone can make you laugh they can also make you a mouth-watering meal.

This, none the less, is an assumption that had been evident since the mid-1950s. From that decade on, it became increasingly common to open a newspaper or magazine and see, somewhere or other in its pages, some random cooking 'tip' from, of all people, a comedian.

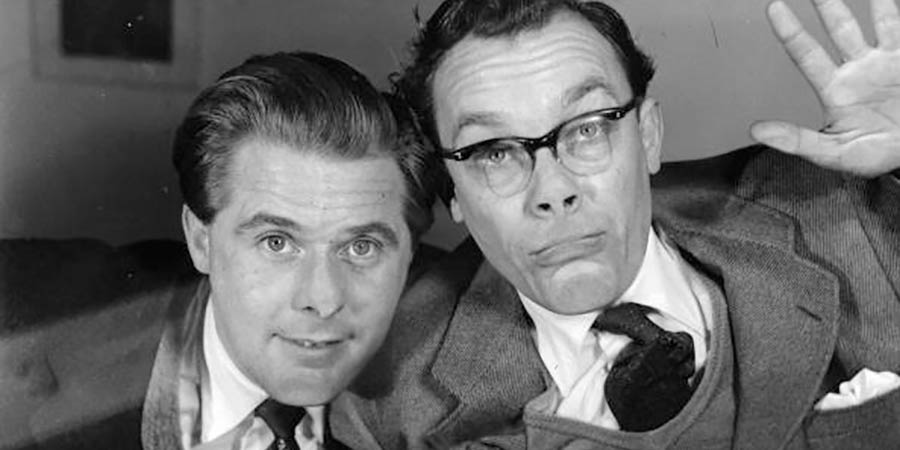

It seems that, in some cases, this was merely considered to be a new means of keeping a comic's name in the public eye. When, for example, Morecambe & Wise were still struggling to establish themselves as a viable double act, their publicist of the time, George Bartram, decided that one way of improving their profile was for him to write in to newspapers and magazines on their behalf - usually without telling them - proffering 'handy' suggestions for preparing food and drink.

Bartram thus started placing such pieces as 'Party ideas from Morecambe and Wise' (which included 'a delicious Christmas drink' called 'Speckled Milk Punch', and another strange beverage termed 'A Bishop' - 'It's for twenty-four people. You need one quart of port...'), as well as individual recipes ranging from 'Eric's Lancashire Hot Pot' to 'Ernie's Yorkshire Parkin'. No feast, function or festive season seemed to go past without the double act's unsolicited dining suggestions.

Eventually, the publicist became so addicted to depicting his two clients as epicurean entertainers that he took to sending in recipes (most of which were 'adapted', increasingly eccentrically, from women's magazines) in the names not only of Morecambe & Wise themselves but also of their wives.

'He was always doing things,' Eric's widow, Joan, would tell me about Bartram. 'He'd send off these recipes to the papers and magazines - in my name! - and then people would write to me and say, "You need your brains testing! What a terrible recipe!" And I'd think, "Well, I didn't send anyone any recipe. What on earth's going on?" And it would turn out to have been good old George.'

Morecambe & Wise soon tired of Bartram's form of food-related ventriloquism and ordered him to try something else (he opted for the fey claim that they collected beer mats), but by this time a number of other comics, spotting the frequency that the double act popped up in the papers, had decided to follow suit. Suddenly there seemed to be a comedian 'sharing' a favourite recipe with the readers in each and every tabloid in the country.

Open one of them up and the reader might have encountered Joan Turner's recommendation for 'Snowman Cake'. Open another and one might have found Jon Pertwee's stage-by-stage advice on how to prepare his favourite 'Iced Buttermilk Soup with Shrimps', or Brian Rix's no-nonsense instructions for 'Tripe and Onions', or Dora Bryan's invitingly precise guide to 'Brandy Pudding', Norman Wisdom's short but quirky description of 'Butter Bean Shepherd's Pie', or Dudley Moore's Curaçao-laced take on Crêpes Suzette, or even (in spite of the fact that he would sooner have invited himself for dinner at a stranger's house rather than attempt to heat something up for himself) Frankie Howerd's supposed 'speciality' dish of 'Braised Oxtail'.

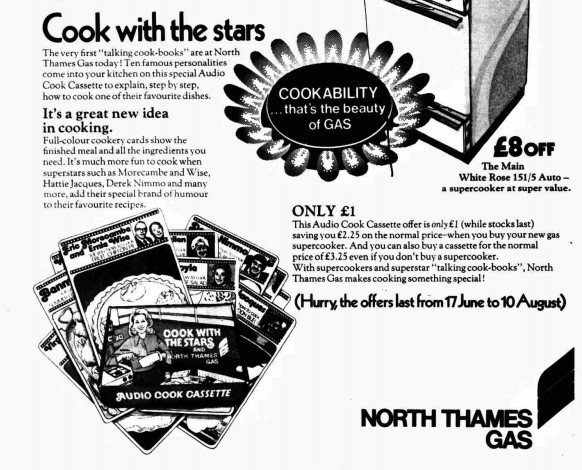

None other than North Thames Gas then got in on the act by offering a special limited edition 'talking cook book' cassette, for the reduced price of just one pound, with each new gas 'supercooker' sold. The cassette ('At any point you can stop the tape and replay the directions') featured ten recipes recorded by such stars as Benny Hill, Derek Nimmo, Wendy Craig, Hattie Jacques and - making a rare return to the genre - Morecambe & Wise, with all of them promising to 'bring their special sort of humour into your kitchen'.

By the start of the 1970s, however, comedians and comic actors seemed to be bringing a greater sense of seriousness and ambition to the idea of 'diversifying' with dishes. Perhaps spurred on by the likes of Vincent Price - whose success touring the US talk shows demonstrating how to cook salmon in a dishwasher saw him rewarded not only with his own UK cooking show (ITV's Cooking Price-Wise, 1971) but also a series of cookbooks - British comedians, or at least their agents, started regarding the kitchen as another place for them to perform. Now, however, they were looking not so much at occasional free recipes in the newspapers (the equivalent of one-off open mic gigs) as lucrative full-length books (the culinary counterpart of a well-paid residency).

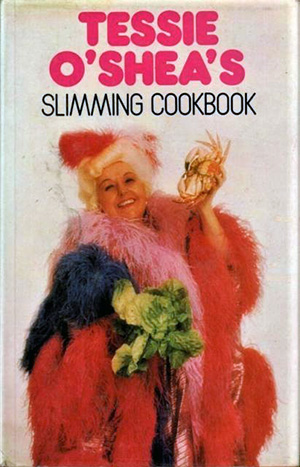

By far the worst of these early ventures into comic cuisine were the diet books. Any comedian or comic actor who had lost a noticeable amount of weight now seemed to get invited to write a celebrity 'health-conscious' cookbook. The problem was that they tended to be not only surprisingly humourless but also somewhat taste-aversive affairs.

The most unappetising of this particular sub-genre was surely the contribution from Tessie O'Shea. Known as 'Two Ton Tessie' (and long associated with the song Nobody Loves A Fat Girl When She's Forty), this somewhat brash and privately irascible comic actor and occasional banjolele player lost just enough weight in the early 1970s for her manager to hit upon the idea of signing her up as quickly as possible for a 'healthy living' publication.

The result was Tessie O'Shea's Slimming Cookbook, a tome with the kind of recipes that would surely have ensured dramatic weight loss through projectile-vomiting if not calorie-controlled dieting. Among her many gag-inducing recommendations were 'Butt-Chive Cheese Shrimps'; 'Brussels Sprouts (Cream Cheese Type)'; 'Various Fishcakes'; 'Diet Scotch Eggs'; 'Just Discovered Tinned Soup'; 'Hamburgers (Plain Type)'; and the spectacularly inaptly-named 'Fun with Leftover Chicken or Turkey'.

Her pièce de résistance, however, had to be 'Egg Juice' - a hideous-looking concoction involving '3 hard-boiled eggs, ½ cup V-8 vegetable juice, 2 tablespoons mayonnaise and pepper to taste'. It was, she claimed defiantly, 'very good with shrimps' when placed on a bed of shredded lettuce.

Diana Dors managed to improve at least a little on O'Shea's austerity-style repasts when, a few years later, she published her own calorie-conscious cookbook, X-cel: 60 Diet Recipes. The volume was arguably somewhat overly fibre-friendly, featuring as it did such roughage-heavy dishes as 'Breakfast Bean Omelette', 'Breakfast Prunes', 'Artichoke Bean Bowl' and 'Flageolet Beans with Tuna', but she kept her focus remorselessly, following through, so to speak, with an explosive-sounding recipe for a low-fat Bhuna Ghosht.

It did not take long, mercifully, before comedians and publishers alike realised that the more commercial option was for more playful and characterful literary ventures, and so the cookbook came to resemble a kind of culinary equivalent of the comedy book or album. The idea was that one bought it primarily for the comic personality, while hoping that at least some of the recipes might turn out to be worth trying.

The first out of the tracks in this funny-foodie field was the Carry On star Jack Douglas, who was actually a genuinely accomplished cook as well as an in-demand comic actor. His The Wu-Hey To Better Cooking (1975), 'co-authored' with his twitchy alter-ego Alf Ippititimus, offered a mixture of humorous patter and low-priced platters ('Damn good grub at a low price') for, well, anyone who was vaguely curious. It sold well enough not only for him to threaten to write a sequel specially aimed at bachelors (full of 'special concoctions for wooing the ladies!'), but also to suggest that - with no disrespect to the likeable Douglas - if a rather bigger comic star came up with a menu or two, there might be a decent market for this kind of thing.

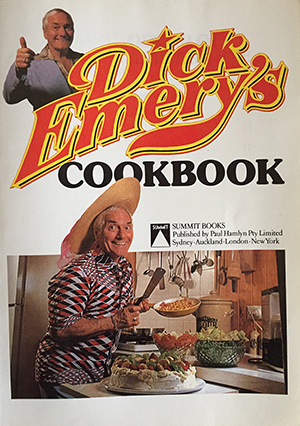

This was where Dick Emery came in. Dick Emery's Cookbook would be the most eye-catching, and peculiar, contribution of all to this odd little sub-genre. Billed as 'a recipe for lots of fun', it claimed to have been inspired by the fact that the star was 'a dab hand in the kitchen', but was conceived mainly as a way to make the most of his current popularity.

The Dick Emery Show had been a fixture on British TV since the early Sixties (it would actually run on the BBC all the way from 1963 to 1981), attracting at its peak as many as 17m viewers every week. A forerunner of the likes of The Fast Show and Little Britain, it was a quick-moving and catchphrase-heavy sketch show in which the star used his fine gift for character acting to play a wide range of personalities, including a toothy Bible-cuddling country vicar ('As the Good Book says...'); the gormless would-be bad boy Gaylord ('Dad - I think I got it wrong again!'); Hettie, a sex-starved single woman; a cheerfully camp cove called Clarence ('Oh, hello, Honky Tonks!'); the leather-clad motorcyclist Ton-Up Boy; a disarmingly urbane tramp named College; a doddery old pensioner called Lampwick; and a friendly but easily-offended 'blonde bombshell' called Mandy ('Ooh, you are awful - but I like you!').

1979, however, was a particularly special year for Dick Emery, because he had temporarily left the BBC (for a huge amount of money) to make The Dick Emery Comedy Hour for ITV, and it had immediately topped the ratings, with 15.5m, as the most-watched show of the week. There was, it was decided, only one way to celebrate that kind of success: he was signed up to write a cookbook.

Dick Emery's Cookbook was published by Paul Hamlyn. It was big, colourful and it was also really quite strange.

The reader ought to have heard the alarm bells going off as soon as he or she opened up the cover. Emery's introduction only takes up a page and a half, but it is, quite frankly, all over the place.

First there is the depiction of himself as a much-admired amateur chef who has been practically pushed into print by his finger-licking friends: 'People,' he claims, 'were always saying to me: "You're not a bad cook, Dick. Why don't you do a cookbook?"' (Were they, Dick? Were they really?)

Then, contrarily, there is the rather tetchy suggestion that he has pushed himself into print in order to prove a point to the very same people: 'When some of my mates say I can't boil an egg, well, that's just ridiculous'.

Dwelling on this misleading perception of himself, Emery continues with his own MasterChef-style blub-inducing backstory: 'People might think it's a bit of a novelty for me to be involved in cooking, but actually I've been doing it since I was nine. My Dad left home before that and my Mum was working at night as a theatre critic, so there was nobody at home and I had to do the cooking. I learnt to make veal and ham pies with fluffy pastry and I could do a roast dinner and sponge cakes'.

It is when he tries to explain the particular culinary skills of the adult Emery, however, that he really starts whisking himself into a fluffy cream of incoherence. After boasting about his large library of Cordon Bleu cookbooks, for example, he confounds the anticipation of haute cuisine-style recipes by confessing: 'I won't say that I'm a gourmet - I can't because actually I prefer plain cooking to exotic food, and the spiced-up foods, well, they just don't agree with me'.

So what kind of cook, then, does Dick go on to claim to be? He does not seem sure himself.

In one passage he is Emery the gastronomic sceptic, the suck-it-and-see pragmatist, the down-to-earth amateur: 'I think a lot of cooking is common sense,' he declares. 'If you're cooking a joint you may not know much about it, but everybody knows you give it so many minutes per pound, stick a knife in it to check the juices, keep an eye on it and taste it with the pan juices occasionally - that makes it cook beautifully'.

In another passage, however - perhaps realising that this approach hardly holds out much pedagogic promise to his eager readers - he styles himself as something of a risk-taking epicurean artiste: 'I like to muck around in the kitchen and invent things. My tastes are sort of high and low. I like sausages and mash and baked beans on toast, and then sometimes I like to cook myself something along the lines of Zen cookery, which is mainly rice, and you cut up some carrots like matchsticks and then fry it all in a big wok'.

By now he has thoroughly confused himself as well as everyone else. He is the visionary who thinks up basic things that have always existed ('I like baked potatoes in their jackets, and best of all when you take out the insides and mash them up with cheese or ham, bacon or some chives or even mushrooms, and then stuff it all back in. I have a lot of ideas like that'). He is the thwarted vegetable specialist ('I love onions, but onions don't love me'). He is also the fast-paced TikTok-style foodie (in stark contrast to his similarly kitchen-oriented friend Michael Bentine, who, he points out about the Peruvian palate-pleaser's last dinner party, 'started at five and we didn't eat till ten').

Most of all, it seems, he is a chucker. He has bought a crock-pot, he reveals, so that he can make stews via the chucking method: 'My favourite is the Chuck'er-in' Stew. You can chuck in anything you like!' Most of his other cooking containers, he admits, end up serving the same purpose: 'I get my wok out and chuck everything into it'.

This wriggling from one cheffy persona to another was probably inevitable from Emery. A very insecure man in real life, he dreaded those 'And this is me' moments on television when, occasionally, he would appear at the end of a show to thank people for watching. Much like Benny Hill, who for a while did a similar thing, he would stand in front of the cameras, eyes darting anxiously from side to side, hands rubbing together nervously, and flash a forced smile before fleeing back out of sight. This was not a man who was comfortable inside his own skin; this was a man who was only comfortable inside some other character's skin.

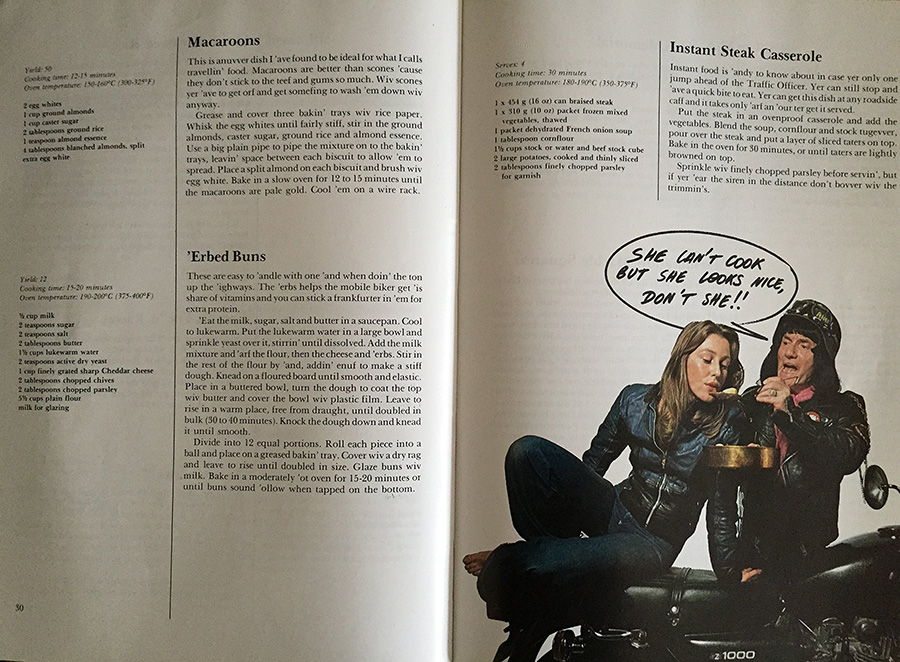

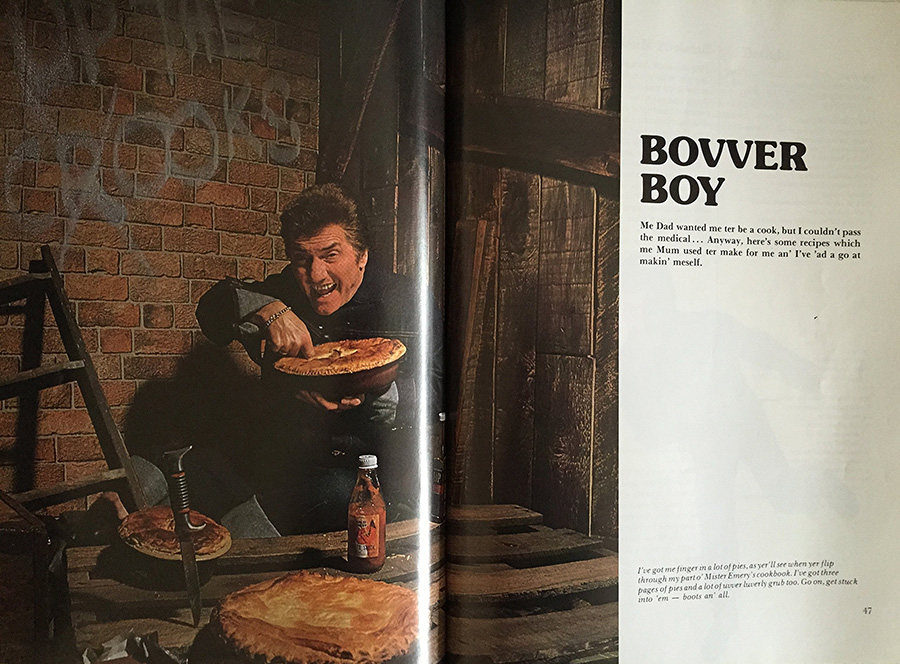

It comes as no surprise, therefore, when The Dick Emery Cookbook, after the twitchiness of its introduction, has the author proceed by hiding behind the personae of some of his best-known TV comic characters, including Lampwick, Ton-Up Boy, Mandy, Bovver Boy, Clarence and the Vicar. What does come as a bit of a surprise, however, is that the variety of the figures has so little effect on the sameness of the food.

Many of the recipes, from one host to the next, seem stuck together in the same Seventies stodge redolent of a world of Wimpy bars, Smash, Findus Crispy Pancakes, Angel Delight, Sunday roasts and an awful lot of suet. Take, for example, Lampwick, whose foodie portfolio includes such ancient staples as 'Bread Puddin,' 'Bread and Butter Puddin,' 'Lampwick's Roast Lamb,' 'Roast Beef wif Yorkshire Puddin,' 'Fish Cakes' and 'Meat Loaf'; along with Ton-Up Boy, whose own less-than-diverse menu boasts of 'Bread 'n' Butter Custard,' 'Onion 'n Cheese Pie,' 'Fish 'n Chips,' 'Crusted Corned Beef,' 'Macaroons' and 'Meat Loaf Memorial'.

In all, there are eight separate recipes for pies, seven for puddings, four for stews and three for dumplings. It is not quite as shamelessly samey as Monty Python's spam-centric café from the same era, but it is getting there.

Part of the problem is the set of characters that Emery has chosen. With Lampwick too backward-looking, Ton-Up Boy too sexist and Bovver Boy too stupid, he has already saddled himself with three chapters where, if he wants to keep up with the conceit, he can only offer up the kind of plain and simple masculine culinary exercises (otherwise known under the manly umbrella of 'heating things up') that would have struggled to make the wipe-down laminated menu of even the most insalubrious of Seventies factory canteens.

Ponder, for example, Lampwick's almost belligerently simple 'Plain Roast Chicken' ('Cook it in the oven for an 'our or so, bastin' it occasionally, until it's tender and golden all over. Luvly, ain't it?'), or Ton-Up Boy's 'Scotch Eggs' ('This is a loverly bit of nosh to get yer bird to make up and pack in the saddlebags if yer plannin' to do a bit of tourin'...') or, if you can bear it, Bovver Boy's ominously-titled 'Bovver Boy's Delight' ('First 'eat the drippin' in a pan, mix all the leftover veggies tugevver, add the salt and pepper and fry the lot until it's nice and brown').

Feeling peckish yet? Thought not.

These, ideally, would have been the sections that would have benefited most from the input of the huge team of first-rate comedy writers who supplied Emery and his characters with funny material on the screen. On the page, alas, Emery is on his own, and the crucial ingredient of humour is barely noticeable, as this example makes painfully clear:

Lampwick's Meat Loaf

Serves: 4-6

Cooking time: one hour

Oven temperature: 180-190°C (350-375°F)Ingredients:

750g (½ lb) minced beef

¾ cup dry breadcrumbs

1 onion, grated

½ cup grated carrot

2 tablespoons finely chopped green capsicum (optional)

¼ cup tomato purée

¼ cup milk

1 egg

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

½ teaspoon mixed herbs

1½ teaspoons salt

Freshly ground black pepperMethod:

Now 'ere's a lively dish which reminds me of me son-in-law, Ernie.Put the beef in a mixin' pot. In another bowl blend together the breadcrumbs, onion, carrot, capsicum, tomato purée and the milk. Stir in the beaten egg, 'erbs and seasonin'. Combine the mixture wif the minced beef and blend the ingredients lightly together until well mixed. Spoon this into a greased loaf tin and bake it in a moderately 'ot oven for an 'our. Drain off the liquid and turn the loaf onto a warm servin' platter.

The range and quality of recipes does improve, mercifully, in those chapters hosted by Mandy, Clarence and the Vicar, presumably due to the prejudices of the period - namely, that only a woman, a camp man or an eccentric loner would have any semi-serious interest in such an effete activity as cooking. Even then, however, the dishes on show leave a great deal to be desired.

The flirtatious Mandy, for instance, exudes a Berni Inn-style level of 1970s sophistication, serving up such oddly impersonal concoctions as 'Chocolate Fondue', 'Baked Apple Dumplings', 'Beef Bourguignonne', 'Chicken Liver Pate', 'Strawberry Tart' and 'Fruity Fritters'. Emery, as a consequence, is reduced to shoehorning in such laboured 'comic' lines as: 'It's luvly with cream, ice cream, or hot custard. Sometimes I have mine with nothing on,' or 'I like to have it on the table all the time'.

The Clarence chapter is far more characterful, but not in a good way. It can really only be read, from the perspective of our own day and age, through the lattice gaps between your fingers, with a tightly-knotted stomach and a near-constant 'Oh, please, don't say what I think you're going to say' cry echoing loudly inside your head like a Gordon Ramsay growl.

Starting and finishing with a couple of predictable rictus grin digs in the ribs - 'Coq au Vin' ('Oooh, this French dish has a lovely ring to it, don't you think?') and 'Spotted Dick' ('You don't see these too often these days, more's the pity!') - the majority of what passes in between ('Light Fruit Cake'; 'Honey Fruit Pie'; 'Fruit and Walnut Roll') suggests a decidedly unpalatable obsession. On the screen, for all its stereotypical faults, Emery actually used to play Clarence with real affection, but on the page the characterisation has just been boiled down to a cheerless cliché.

It comes as quite a blessed relief, therefore, when the book concludes with the Vicar's contribution, which, like the buttons and foreign coins slipped onto the collection tray in church, proves a real ragbag of random but inoffensive bits and pieces, including 'Chicken Livers Bordelaise', 'Lamb Boulangère', 'Duck with Sour Cherries', 'Peanut Butter Cookies', 'Coffee Cake Offering' and 'Crunchy Cod Fingers'. The harmless Anglican, with his toothy, non-violent grin, simply guides us to the end, as usual, with the minimum of fuss.

What, after the cookbook has been put (or dropped) down, has been the experience of reading this strangely subdued mixture of sketch comedy and even sketchier recipes? The answer is surely a strong sense of dissatisfaction in terms both of food and funniness.

Remarkably, however, the book sold very well at the time, not only in Britain but in Australia, too - where Emery's TV shows also enjoyed a large and loyal following. The star, none the less, in spite of such success, was wise enough not to stretch himself as far as a second volume, and, instead, opted to concentrate again on his television work.

The lesson of his own venture into the genre of the comedy book was that it is not a format that one can enter half-cocked - nor, indeed, under-cooked. The best humorous books that had emerged earlier on in the decade had worked because their authors had taken them seriously, and treated them as proper comic performances just like any other. Emery's entry, in contrast, seemed to symbolise the declining appetite for such a commitment.

The comedy book would soon be brushed aside by the burgeoning home video market, and comedians would come to find that it was far more lucrative, as well as far less time-consuming, to package existing material on tape instead of conjuring up new ideas for the page. That was inevitable, but also, perhaps, just a little sad.

As for The Dick Emery Cookbook, however, the sad thing is not that it is now long out of print and hard to find, but rather that his comedy shows, these days, are almost as obscure. He might not have been much good as an author or a cook, but, in the medium of television, he was one of the best comic performers of his time.

Rather than seek out his recipes, therefore, we should perhaps make some effort to retrieve his sketch shows. They might seem, like his cook book, a little dated in terms of taste, but the menu is impressively varied, and the sauce, even now, is surprisingly hard to resist.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreThe Jack Douglas & Alf Ippititimus Wu-Hey To Better Cooking

At first, we were under the impression that Jack and Alf were one and the same man, but it seems we have a Jekyll and Hyde on our hands. This has created a feeling of jealousy between the two, which borders on the irrational.

For instance, when Jack was waxing eloquently about "Peaches in Kirsch," Alf butted in with, "Don't do you as much good as pea soup." So we included both. Even Alf's granny got in on the act.

Jack's friends (Shirley Bassey, Bruce Forsyth, William Franklyn, Matt Monro, and Barbara Windsor), however, all obviously talented and intelligent people, gave us no trouble at all. With their help, we are confident that the book is delightful in its informality, and invaluable in that it provides a means for today's cooks to provide a "different" kind of menu within their budget.

First published: Monday 10th November 1975

- Publisher: Golden Eagle Press

- Pages: 160

- Catalogue: 9780901482235

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 1st January 1976

- Publisher: Golden Eagle Press

- Pages: 160

- Catalogue: 9781984344656

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Dick Emery's Cookbook

British comedian Dick Emery is known throughout the world for his gallery of hilarious and unforgettable characters ... Lampwick, the doddering relic of World War I; Mandy, the coy blonde with the knockout punch; the uncouth Bovver Boy; the Vicar with the teeth and the platitudes; the Ton-Up Boy with his leather gear, his bike and his birds; the outrageously camp Clarence; and a host of others.

What is not so well known is that Dick is also a dab hand in the kitchen. He's been at it since he was nine, and even today often relaxes by "mucking around" (as he puts it) in the kitchen and inventing things.

Friends often prodded Dick about his cooking and said he should produce a cookbook. Dick liked the idea but wasn't sure he had the time. There were others, however, who had no such reservations. Lampwick quickly volunteered to "give it a go", Mandy was simply bursting to reveal her culinary skills and the Vicar was delighted to make a generous offering to such a worthy cause. Bovver Boy, Clarence and the Ton-Up Boy were soon clamouring to be in on the act too, so Dick just hadned it over and here we have it - Dick Emery's Cookbook, compiled by six of his favourite characters, with all their favourite dishes and hteir own inimitable way of telling you how to do them.

It's a recipe for lots of fun.

First published: Monday 1st January 1979

- Publisher: Summersdale

- Catalogue: 0727103865

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.