Oh yes!: The comic guile of Deryck Guyler

For much of the Sixties and Seventies on British television, Deryck Guyler was the comic embodiment of the Jobsworth - the most familiar focus for instances of small-time officialdom's routine pettiness, self-protective slothfulness and prosaic pettifoggery. If ever a sitcom required a low-ranked authority figure to hold up a hand, shake a head and tell another character that, no, no, no, they really can't be doing that, then Deryck Guyler donned the disguise.

He was Corky Turnbull, the comfortably dumb police constable in Sykes. He was Norman Potter, the easily-rattled school caretaker in Please Sir!. He popped up elsewhere on the screen as a variety of reluctantly-roused civil servants, muttering magistrates, stubbornly slow-moving bank clerks, people-phobic porters, whistle-rash train guards and tetchily ticket-ready traffic wardens.

Specialising in types situated one rung down from those played by the more urbane Richard Wattis - the ones more likely to be found furrowing their brows in and around the factory floors - Deryck Guyler was British comedy's quintessential gatekeeper, the most vivid and believable incarnation of the kind of public servant who deeply resents the assumption that he is supposed to be serving the public. No one else could utter British officialdom's traditional sullen inquiry - 'And what do you want?' - with such an authentic sense of world-weary irritation.

He was actually, off the screen, quite the opposite kind of character - warm, considerate, very modest and always happy to help others, so much so that he was commonly regarded as being one of the nicest performers in his profession. How he came to corner comedy's market in people displeasers is thus quite an odd sort of story.

Born on 29 April 1914 in Wallasey, on the Cheshire side of the Mersey, he grew up in a middle-class family wealthy enough (his father had inherited a jewellery shop - Green and Guyler - in Sefton Park) to send him to Liverpool College, a public school known since Victorian times for producing a steady procession of strongly moral mandarins, politicians and priests. The experience made Guyler deeply religious, to the extent that, upon leaving, he even envisaged himself as a man for the ministry and studied for a year at a Church of England theological college.

His other early interest, however, was music. He first became a drummer, pounding away cheerfully at the back of a local amateur band, before being seduced by, of all things, an item normally associated with the chores of laundry.

In June 1935, aged twenty-one, he was present in the audience when an American jazz band called The Washboard Serenaders played at the Liverpool Empire. Distinctive for their inspired use of unorthodox instruments, such as the kazoo and spoons, they featured, in place of a drummer, a washboard virtuoso called Bruce Johnson, whose skill at summoning such a range of sounds and rhythms from just a ridged piece of wood fascinated the young Guyler so much that he promptly sold his own drum kit to a neighbouring policeman and bought himself a washboard instead, added the requisite bells and whistles, and taught himself every technique and trick until he was as good at the odd art as just about anyone else in the country.

He soon found, alas, that the demand for washboard instrumentalists was somewhat limited on the Wirral, but, now 'bitten by the performing bug', he could not bear to leave the stage. He thus persuaded his parents to pay for some elocution lessons and then joined the Liverpool Rep, playing all kinds of parts, including ones written by Shakespeare, Molière and Shaw. Colleagues in his final season there would include Michael Redgrave, Rex Harrison, Robert Donat and Diana Wynyard.

The outbreak of war proved only a brief interruption of his acting career - he joined the RAF as a police instructor after being called up but was invalided out in 1942 (he suffered from unbalanced vision). He then toured home and abroad as a member of the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA), learning the craft of sketch comedy, before joining the BBC Drama Repertory Company ('They were short of actors at the time'), where his many straight roles included Macduff to Sir John Gielgud's Macbeth and Brutus in Julius Caesar.

It was ironic that, having only recently succeeded in completely erasing the last traces of his northern accent (it had always been more of a soft Woollyback strain rather than the harder Scouse sound), he suddenly found himself obliged to unpack it again, and then some, to qualify for his first major project. The radio comedy ITMA wanted him to join its cast.

Hosted by the fast-talking Tommy Handley, the show had been one of the biggest hits of the wartime era, but was now looking to freshen-up its act. Guyler was hired to play, amongst other characters (such as Percy Palaver and Sir Short Supply), a slow-talking laid-back Scouser who was frequently bemused by his friend's broader vocabulary (e.g.: HANDLEY: 'Never in the whole of my three-hundred ITMAs have I heard such a piece of concentrated cacophony!' GUYLER: 'What's a concentrated cacophony???').

The Toxteth-born Handley, relishing the chance to interact with a fellow Merseysider, soon started ad-libbing to him a succession of references that would only make sense to people who hailed from that part of the country. On one occasion, for example, Handley said, 'You stand there, looking like a collision mat with glasses on' (referring to the coconut coverings that protected the sides of the Mersey ferry boats); in another broadcast - for which Guyler was sporting a thick beard - he said, 'You stand there looking like the underside of New Brighton pier at low tide' (an allusion to the seaweed hanging from the concrete groynes); and on a number of occasions, when his character said something especially odd or ignorant, Handley would exclaim, 'Why, I'll kiss Ma Egerton!' (she was a Liverpool pub landlady).

After Guyler's first few appearances, Handley suddenly introduced him, unscripted, as 'Frisby Dyke'. Frisby Dyke had been a grand department store in Liverpool's Lord Street but had gone bust and then been bombed during the Second World War. The name stuck, and Frisby Dyke became the first radio character to speak with a reasonably authentic Liverpudlian accent (the Liverpool Echo, indeed, would often credit the actor for sparking 'the spreading of that gospel of sound').

The rambling and often downright surreal exchanges between Handley and Dyke, which were made to sound all the more exotic thanks to all the Liverpool in-jokes, rapidly became one of the highlights of the show during its final few years on air:

HANDLEY: I don't mind telling you I'm completely flabbergasted!

DYKE: What's 'flabbergasted'?

HANDLEY: You mean to stand there, a perfect example of Frisbius Dykus Genus Liverpudlicus, and say you don't know what flabbergasted means?

DYKE: Never heard of it.

HANDLEY: Well - I'll push over a cocky watchman's hut! You know the zoo at Otterspool?

DYKE: Yes.

HANDLEY: Well, they had a flabber there. And it was always being gasted.

DYKE: Is that a fact?

HANDLEY: Well, me Aunt Irma said so. Didn't you ever see it?

DYKE: No. Me dad wouldn't take me.

HANDLEY: Why not?

DYKE: Well, he suffered from the baboons.

HANDLEY: 'Suffered from the baboons'? What the Old Mother Noblett are you talking about?

DYKE: Well, the baboons used to throw the nuts back at him.

HANDLEY: Why?

DYKE: Well, he had side whiskers and a blue top lip.

HANDLEY: Fancy that!

[A 'cocky watchman' was a Scouse phrase for an elderly security guard; Otterspool zoo, in Liverpool, had closed down in the 1930s; Mother Noblett was the company that made Everton mints.]

After ITMA ended with Handley's premature death in 1949, Guyler continued to be in great demand on the radio both for his wide range of dialects and also his gifts as a character actor. He was a regular, for example, in Eric Barker's gently whimsical Just Fancy (1951-7), and from the middle of the following decade he would feature, from the third series onwards, as the civil servant Deryck Lennox-Brown in the long-running Whitehall-based sitcom The Men From The Ministry (1966-80).

The only unhappy aspect of these radio days was Guyler's somewhat farcical long-running battle to win himself an official parking space at Broadcasting House. His artist's file at the BBC's written archives centre bulges with correspondence relating to his clashes with those sniffy Corporation bureaucrats who kept chastising him for leaving his vehicle in the space alongside All Souls Church in Langham Place ('which is normally reserved for staff cars or those which are liable to be required urgently'). This all-too typical piece of BBC pettifoggery dragged on for so long that it drove Guyler to threaten to withdraw his services completely (his letter saying so provoked the rather sinister response: 'We are taking note of this'), but he did, eventually, get the access that he had craved, and his radio career continued.

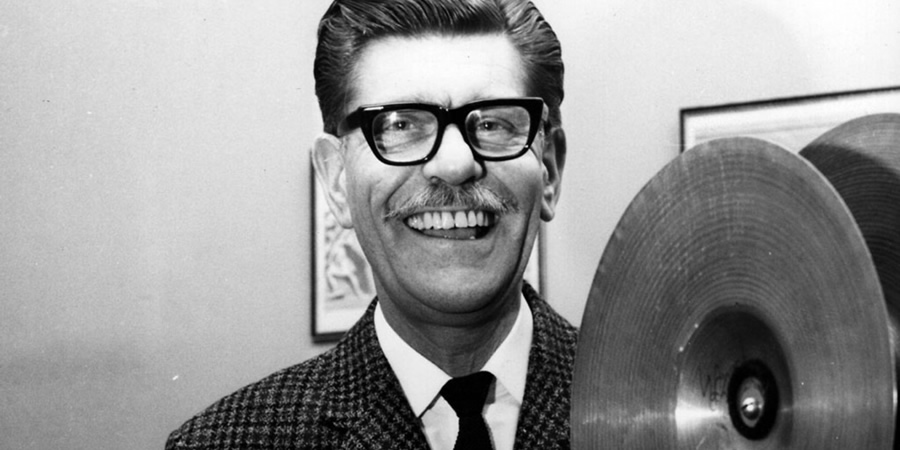

Although sound would, in many ways, remain his favourite medium, because it allowed him to make full use of his versatility (he would feature, in total, in an estimated six thousand broadcasts, and the faux news announcement that he recorded in 1946 for The Mousetrap would continue to be played in that long-running stage production throughout - and indeed beyond - the rest of his life), it was not long before his distinctive physical features found him plenty of work in pictures. With that thick and smartly-slicked-back brown hair, black spectacles, military-style moustache and deep whisky-rich timbre, he had always seemed fifty-something, even when he had been thirty-something, and now he had grown into the kind of characters that every comedy show seemed to crave.

The sitcom with which he would probably become most closely associated would be Sykes. Joining the cast (which also included his old ITMA colleague, Hattie Jacques) during its first series in 1960, his role, as PC Corky Turnbull, was only meant to be an occasional, and minor, part, but, as Eric Sykes would later acknowledge, 'his popularity with the public grew more quickly than weeds on a bombsite', and, as a consequence, he was given more and more to do.

Corky was a character who evolved, via a creative collaboration between Guyler and Sykes, as the show went on through the next couple of decades, from a fairly unsympathetic authority figure with his notebook and pencil always poised and ready to record a minor infraction ('Ah-ha - I've got you this time, eh!') to more of a flawed family friend who was always happy to pop in and have a casual chat (he even, in one episode, had Eric and Hat over to his place for a Christmas party).

'Eventually,' Eric Sykes would recall, 'we had him make this distinction: "Helmet on: Constable. Helmet off: Corky," so he could do both - the tough character and the soft character - and he was so good at it. And he could switch from one to the other so naturally it always seemed to make perfect sense, how that helmet, on or off, changed him. Deryck was a very clever actor'.

Arguably Guyler's most iconic performance, however, would be as the chronically irascible school dogsbody Norman Potter in the LWT sitcom Please Sir! (1968 to 1972). Potter's first appearance, in the opening episode, set the tone very well for all of the jobsworthian interventions to come when he arrived in the playground, bristling with uniformed self-importance, to find the new teacher, Mr Hedges, pushing through a gate that has been kept shut by a stray crate of milk:

POTTER: Where do you think you're going with that?

HEDGES: Well, I'm, er, just moving it. Silly place for milk.

POTTER: I put that there.

HEDGES: Oh, well, no offence, but it was blocking the gate. People want to get in.

POTTER: Not through that gate they don't! Nor out!

HEDGES: What do they do, then - jump over the wall?

POTTER: If you'll just allow me to explain: that gate is there solely, you see, for my purposes.

HEDGES: Oh, you're the milkman, are you?

POTTER: I am Mr Potter!

HEDGES: Oh, yes?

POTTER: Yes! The school keeper 'ere.

HEDGES: Oh! Hello. I'm Bernard Hedges, the new teacher.

POTTER: And I suppose that makes everything all right, does it?

HEDGES: Well, er, it should help.

POTTER: You've never seen Miss Ewell come through that gate, and she's the Assistant Headmaster!

HEDGES: But I came the wrong way!

POTTER: You've never seen any of the staff use that gate! But along you come - oh, yes, as bold as brass - and start kicking my blue tops about!

HEDGES: 'Kicking'? Look: I'm new, I came through the wrong gate, I'm sorry - all right?

POTTER: Being sorry doesn't make it 'all right,' does it?

HEDGES: Well, hard luck!

POTTER: Is that all you've got to say?

HEDGES: Look, what do you want - a written apology?

POTTER: A little bit of civility wouldn't come amiss, y'know!

HEDGES: Oh, don't be so damned stupid!

POTTER: Hey! Don't you walk away from me! Ha - I am taking your name!

HEDGES: You're doing what??

POTTER: Taking your name! Right, now then: how do you spell 'Edges?

HEDGES: Hedges? E-D-G-HE-HES.

POTTER: '...HE...HES'. Right. This isn't just a notebook, y'know! Oh, no. This is a report notebook!

Guyler's Potter (who was conceived originally as a Cockney until the actor insisted on playing him as a Lancastrian) was a magnificent comic creation: dark gimlet eyes glaring through the glasses, neck craning forwards, jaw jutting out, with a volcanic core of anger, hurt and resentment bubbling away inside of him, forever on the verge of bursting out. He was the classic working-class misfit, the belligerently contented slave, pushing around the many who looked vulnerable enough to be intimidated, while creeping meekly around the few - mainly the headmaster - who struck him as above and beyond his bullying brief.

Countless other actors had played that type, but none did it so well as Guyler. The stiff-backed way he patrolled the corridors, the way the flesh on his face seemed to stretch and strain in outrage at the sight of anything or anyone out of place, the snail-trail of sneery satisfaction that spread across his lips as he stated the reasons for stopping others from getting something done - it was a masterclass in satirical misanthropy, eliciting instant nods of recognition from the millions watching at home who had been exasperated by the real thing in every sphere of social life.

Potter grew in prominence in terms of plots when John Alderton, who played Hedges, left the cast in 1971. Pitted from this point on more intensely against the unruly pupils, it was a classic case of a methodical minor authority figure striving to do something akin to herding cats, and, although the situations were far more forced than before, Guyler (in spite of not being particularly happy with the consequent changes) helped sustain the popularity of the show, as well as further enhanced the comedic appeal of his own character.

By the early Seventies, the combination of Sykes and Please Sir! had helped make Guyler a household name, even though he was still being limited to being a supporting player. It did not seem to bother him, however, as he stressed how content he was just to be part of a team. 'It is nice to be second on the bridge', he reflected. 'You have a steady flow of work and less responsibility'.

His one starring vehicle was made in, of all places, New Zealand. Written by the hugely experienced sitcom specialist Vince Powell (Here's Harry, George And The Dragon, Never Mind The Quality Feel The Width, Nearest And Dearest, Bless This House, Love Thy Neighbour), it was called An Age Apart, and featured Guyler as sixty-five-year-old Walter Atherton - a downbeat Lancastrian who, even though he has never ventured any further than his local pub, has now accepted an offer from his widowed daughter to emigrate and live with her in New Zealand with her and her young son.

This sitcom had actually undergone a peculiar evolution prior to Guyler's involvement. What had happened was that the broadcaster TVNZ had bought the format rights for Powell's earlier Thames TV series, Spring & Autumn (1972-76) - which starred Jimmy Jewel as an elderly man who has befriended a teenage loner - and wanted it adapted for a New Zealand audience.

Tom Parkinson, TVNZ's Head of Entertainment, suggested to Powell that Jewel's character could have upped sticks and gone to New Zealand to live there with his recently-widowed sister and her Māori son. Powell was happy enough with that brief to go ahead and write a pilot episode (under the new title of You're Only Young Twice), which Parkinson duly accepted, only to be disappointed by the news that Jewel was going to be unavailable for filming.

With TVNZ still keen to commission a series, the decision was made to revise the basic storyline to suit another actor, and Deryck Guyler was Powell's choice to take on the part. Guyler, upon receiving the invitation, was delighted to accept - on condition that the production company paid for his wife, Paddy, to accompany him throughout the project. Once Paddy's presence was assured, he was excited at the prospect of finally being at the very centre of his own sitcom.

Bridget Armstrong, a Dunedin-born actor who had worked in the UK as well as on many shows closer to home, was cast as the daughter, while a local teenager, Jason Pirihi, was picked to play her son.

The storylines ploughed a familiar familial field. An emotional triangle of father, daughter and grandson, there were clashes of a generational and cultural character, with Guyler being given more opportunities than he had been previously afforded to blend the dramatic with the comic and produce a more intimate style of portrayal.

Filmed in Auckland and screened during the spring of 1983, the show was generally well-received (with one especially enthusiastic critic describing it as 'dripping with quiet and gentle good humour', and praising it for providing 'pleasant, positive, refreshing entertainment, with a slight bite'), and there was plenty of enthusiasm within TVNZ to pursue the possibility of making a second series. Before that could happen, however, the sitcom - which had, by New Zealand TV standards, been an expensive project to complete - needed to find a buyer for the Australian market. It ended up failing to do so, and, as a consequence, the second series was cancelled, and Guyler's stint as a star came to an abrupt and premature end.

He was not too disappointed. Back in Britain, he remained a busy and well-regarded supporting actor, booked up far in advance for plenty of new projects, as well as always in demand for what he called his 'bread and butter' jobs: the well-remunerated commercial voiceover engagements (contributing to, amongst many others, Mars' Revels, Heinz soups, Cadbury's Curly Wurlys, the Gateway Building Society, Barclays Bank and Scotch videotapes - 'Re-record not fade away'), as well as several public information films, which made it a rare thing during this period to sit through a commercial break without hearing at least one of his numerous narrations).

It also helped, in terms of dealing with the vagaries of the business, that he had always had a hinterland. Religion was one important aspect of that broader life.

His early interest in theology had only grown stronger over time. A convert to Roman Catholicism in 1945, he was usually to be found, during rehearsals and even in between takes, sitting quietly in a corner, reading the Bible with contented intensity (and he even recorded an album of extracts from the Knox Bible in 1962).

His second passion was for jazz. Describing himself as a 'jazz mad fiend', he had started collecting 78rpm records at the age of ten, and by the time he was in his sixties he was the proud custodian of more than 1,600 vintage discs. His all-time favourite, according to his Desert Island Discs interview, was Crooked Blues by King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band.

A keen supporter of the National Federation of Jazz Organisations, he not only attended many live events over the years, but was also an eager participant whenever a compère was required. In 1951, for example, he hosted a major jazz concert at London's Festival Hall, introducing in the presence of the then-Princess Elizabeth such acts as Mick Mulligan's Magnolia Jazz Band, Humphrey Lyttelton, Freddy Randall, Joe Daniels and Cyril Scutt, and he continued to make similar appearances throughout the following decades.

Outside of the genre of jazz, he was also a great admirer of The Beatles (whom he judged to be 'nice lads'). He therefore jumped at whatever chances arrived to work with any or all of them, such as when he appeared in their movie A Hard Day's Night (1964) - as a typically lugubrious police sergeant - and provided one of the voices - a Scouse one, of course - for the Paul McCartney and Wings animated film The Bruce McMouse Show (1972). 'I got on particularly well with Ringo', he said of the various associations, 'because I am interested in drums and drumming. [We] had long talks on it'.

He also kept up his youthful enthusiasm for playing the washboard. Always delighted to accept any offer to perform, he played live or in the studio on numerous occasions (although, contrary to the relentlessly un-checked urban myth, there does not appear to be any reliable evidence to confirm his participation in any recording sessions by his 'long-time fan Shakin' Stevens').

One of the most enduring of his actual musical associations was with his fellow Merseysiders The Spinners, with whom he often guested in concert ('If ever they're playing in London, they give me a ring and I go along'). He recorded several songs with them over the years on such albums as The Spinners Are In Town (1970) and Last Night We Had A Do (1984), and on one memorable occasion he also joined them to play renditions of Rock Island Line and Freight Train on the BBC's Pebble Mill At One show in 1985.

There were, in addition, some notable on-screen musical cameos, such as a special Children in Need duet with the astronomer Patrick Moore on xylophone. He also not only played the washboard in an episode of The Morecambe & Wise Show (1970) - always a happy collaboration, because he had been great friends with the pair since first working with them during their earliest radio days - but also (in the guise of the Revd Ozzy Stringer, 'four years running the Morecambe and District All-Comers' Spoon and Washboard Champeen') returned to the programme ten years later to demonstrate, with a charming sense of innocent pleasure, his drumming skills as well.

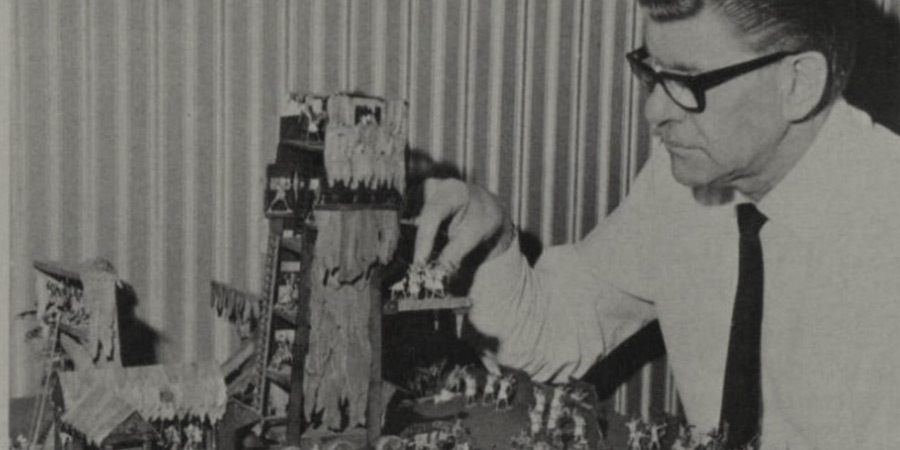

Another interest, perhaps less predictable, was for wargaming. He collected or made more than 15,000 models (including an entire Roman legion), which he painstakingly painted and positioned on a number of miniature battle grounds. A founding member of the Society of Ancients, a group of wargamers specialising in the classical era, he was elected its first president in 1965, and later made an honorary life president (and the Deryck Guyler Award, which was dedicated to his memory in 2008, would be awarded periodically by the Committee for 'Services Promoting the Society of Ancients').

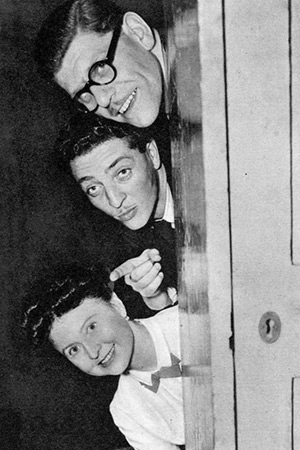

Then there was his devotion to his beloved wife, Paddy. Margaret Mary McConnell, as she was really named, had been a performer herself as part of the three-sister variety harmony act the Lennox Sisters when they married in 1941 (they would go on to have two sons, Peter and Christopher). Enjoying one of the strongest bonds in show business, Eric Sykes, who joined them once on holiday, would note that, even when sharing a swimming pool, they would instinctively synchronise their movements as they swam.

By the early 1990s, Guyler, now some way into his seventies, decided that it was time to retire, and he and Paddy moved from their long-time home in Norbury, South London, to Queensland, Australia, to be nearer to their son Chris, daughter-in-law Judy and three grandchildren. Arriving in November 1993, they lived quietly and happily in the tree-lined suburb of Ashgrove, in the City of Brisbane, until 1997, when, following a number of falls at home, Deryck was admitted to a nearby nursing home.

Paddy moved to Forest Place Retirement Village, which neighboured Deryck's new residence, and visited him daily. He passed away peacefully, on 7 October 1999, at the age of eighty-five years old.

The obituaries all tended to dwell on the curmudgeonly characters for which he was famous, but that only told part of the story. The cliché is that it takes one to know one, but that has never really been true. Sometimes it just takes someone who has made the right choices to reflect on someone who has made the wrong ones.

Deryck Guyler was a nice man who could see straight through the nasty ones. He made a job out of mocking the jobsworths, and he did it delightfully well.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more