Classical gas: Galton & Simpson's Le Pétomane

By the late 1970s, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson were firmly established as two of the doyens of British comedy. Having written not one but two of the most successful and influential sitcoms in history - Hancock's Half Hour and Steptoe And Son - as well as numerous other popular and critically admired shows, they had more than earned the right to do more or less whatever they wanted. What they wanted to do next, however, would surprise and shock many people in show business circles, because what they wanted to do next was a film about a flatulist.

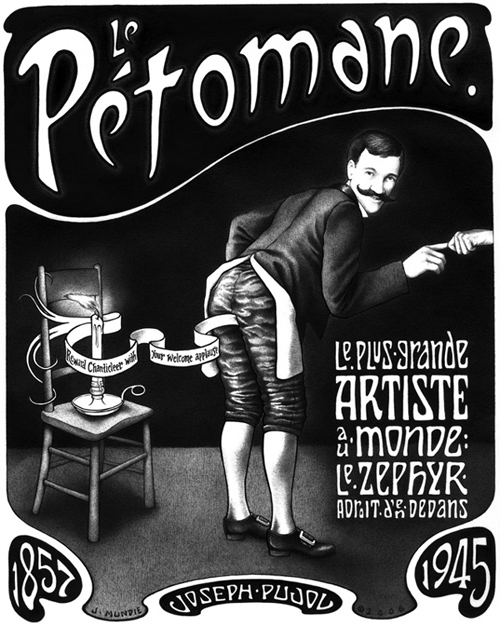

The flatulist in question was a Frenchman called Joseph Pujol, who was better known by his stage name 'Le Pétomane', and he was no ordinary expeller of air but rather a man who strained to make farts into an art. During the last few years of the late nineteenth century, Le Pétomane was the biggest star in France, attracting almost three times as much money to the box office than even 'The Devine' Sarah Bernhardt. The man was a cultural phenomenon: a cultural phenomenon founded on farts.

The Marseille-born Pujol discovered at an early age that he was something of a freak of nature. It happened one summer, when his parents took him to the beach and he started swimming in the sea. Dipping his head underwater while holding his breath, he started to feel a strangely cold sensation spread throughout his stomach.

Puzzled and a little alarmed, he swam back to the shore and ran off to a secluded spot where he could try to assess what had happened. It was at this point, as he relaxed, that about two litres of sea water started spraying out from his behind.

He was concerned enough to consult the family doctor, but was simply told, with an indulgent chuckle, that it was nothing serious, although he should perhaps spend more time on the sand than in the sea. Reassured, he took the advice and moved on with his life, eventually training to be a baker.

It was only a few years later, when Pujol was doing his military service with the 1st Cuirassier Regiment, that, as he sat around with his comrades and shared stories of their respective pasts, the strange experience was recounted. Intrigued and amused, the other soldiers urged him to see if he could reproduce the effect, so he duly sat in a bucket of water, then got up and acted like a waterspout.

Thrilled by the cheers that his actions elicited, Pujol started to train his anus into producing a party piece to entertain the troops. Moving on from water to air, he found that he could control his muscles sufficiently to produce, as one witness put it, 'a veritable fart fantasia' of sounds, which included a distant bugle call, a flurry of rifle shots and the fast-approaching squeaking sound of their sergeant-major's boots.

Even when he returned to civilian life and his bakery, the memory of the applause he had won never threatened to fade from his memory, and he was eager to perform once more. Initially, for propriety's sake, he settled for singing part-time in the local music halls, but, knowing that he was never going to be more than an also-ran when it came to his vocal talents, he soon gave in to the temptation to invest all of his artistry into his very unusual anus.

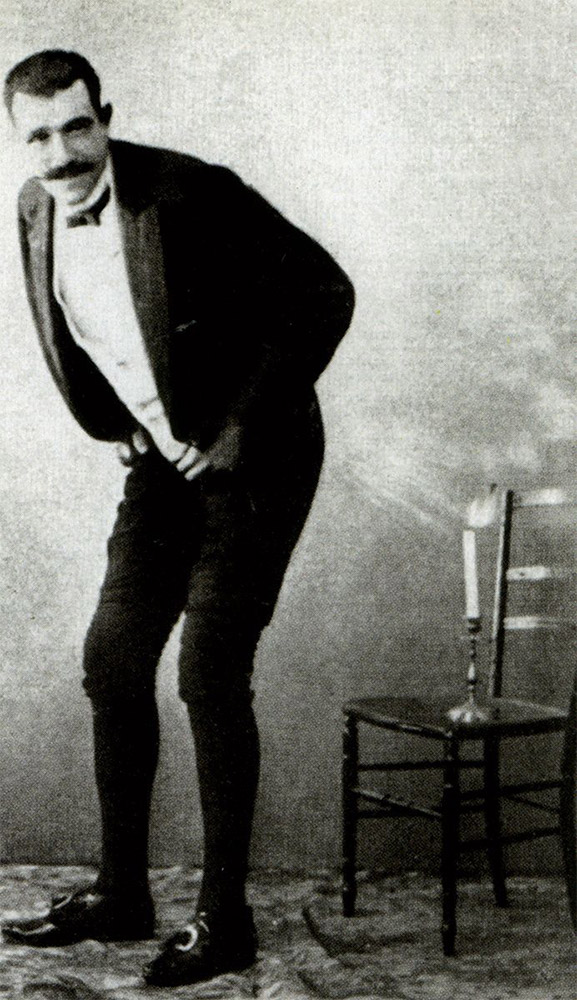

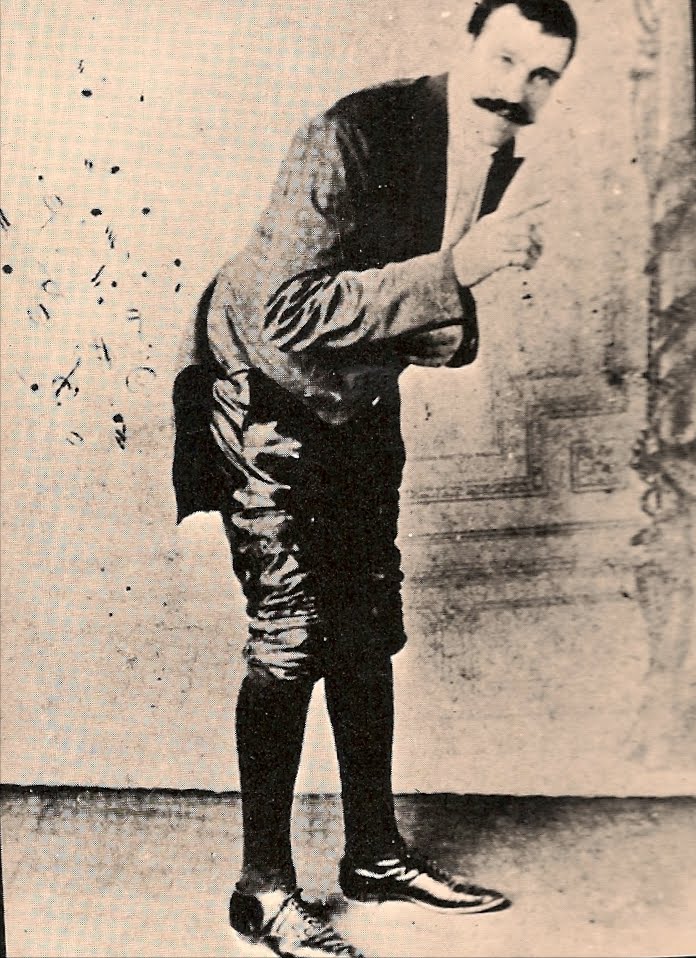

Re-naming himself up-front, and back, as 'Le Pétomane' (roughly translated as 'The Farting Maniac'), he decided to try his luck as a professional flatulist. Pujol did not look like he was destined for stardom - with his black crew-cut hair, large nose, handle-bar moustache, lantern jaw and tall but bland body, he seemed more like an unobtrusive waiter than a commanding performer - and his fledgling fart act certainly did not seem set for fame, but his self-belief was inextinguishable.

Touring the music halls of le Midi, billing himself as 'the only artist who pays no author's royalties,' he would barge into each manager's office, declare boldly, 'My anus is of such elasticity that I can open and shut it at will!,' and then bend down and start farting at different lengths and tones. The managers, in turn, would first recoil in alarm, then observe, listen and reflect, and then book him for the following night.

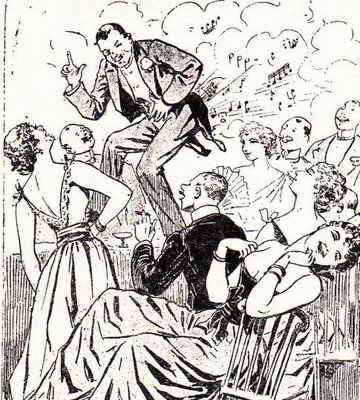

It was the audiences who made the decisive judgement. According to contemporary reports, the response, once the initial shock had worn off, was extraordinary: 'The enthusiasm became delirious,' wrote one observer of Le Pétomane's performance. 'It's almost impossible to imagine the noise people made who wanted to shout even louder, the apoplectic faces, the streaming tears...they needed a good quarter of an hour to get their breath back.'

In 1892, after honing his act in the provinces, he felt he was ready to capture Paris. The manager of the glamorous Moulin Rouge took some persuading, but, following an eye-opening audition, Le Pétomane was set to star in the capital.

Dressed flamboyantly in a red coat with a red silk collar, a white butterfly bow tie, white gloves, black satin breeches ruched at the knee, black silk stockings and black patent leather shoes, he walked smartly on to the stage and announced: 'Ladies and Gentlemen, I have the honour to present a session of Pétomane. The word Pétomane means someone who can break wind at will but don't let your nose worry you. My parents ruined themselves scenting my rectum.'

He then bent forwards with his hands on his knees, as if expecting an acrobat to jump on his back, and proceeded to do his act. It started with a series of 'impressions', such as a little girl (a quick high-pitched fart); a bride on her wedding night (a very tiny, timid, furtive fart); a bride on the morning after her wedding night (a longer and louder fart); a dressmaker tearing two yards of calico; a clap of thunder; and a cannon firing.

He would then nod respectfully to the audience and step backstage for a moment, where he collected a metre-long black rubber tube and inserted one end into his anus and held the other end between his fingers before striding back out into the spotlight. Lighting two cigarettes and placing one in his mouth and the other one in the exposed end of the tube, he proceeded to 'smoke' the second one by expanding and contracting his abdominal muscles to inhale and expel precisely the right puffs of air. He followed this by placing a small flageolet over the tube and playing several short pieces of popular music, starting with 'O Sole Mio' and ending with 'Au clair de la Lune'.

The climax of the act saw him stick a gaily-coloured ocarina into the tube and give a spirited rendition of 'La Marseillaise'. He would then close the event by bowing with his back to a candle and, with a demure little toot, blew out the flame, and then extinguished the row of gas-lit footlights along the front of the stage one by one.

The reaction to this unprecedented performance was so enthusiastic that, within a few days, everyone in Paris seemed to be pouring into the theatre to witness Le Pétomane for themselves. Suddenly, he was the most talked-about star in all of France, and the most trumpeted trumper in history.

As the next few months went by, spurred on by all the acclaim, he started extending his repertoire (other woodwind and brass instruments were involved, as well as coloured face powder and a series of animal noises), and also consented to give some private, men-only, late night shows, which culminated in him (dressed only in a bathing suit with a small hole cut out at the back) lowering himself into a big basin of water, sucking up two litres-worth of liquid into his large intestine, and then rising again to project it all across the stage, at great force, to a distance of about 4.5 meters.

It was this drive to keep progressing and surprising that helped sustain, and further extend, his already remarkable fame. It was not just ordinary members of the public who were now queuing up to catch sight, and sound, of this celebrated flatulist. Many of the grandest figures from the haute monde of the fin de siècle were just as eager to witness his performances, and it was not long before Le Pétomane was able to count the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII of England), King Leopold II of Belgium and Sigmund Freud as among his most avid of fans.

As the audiences continued to grow, so too did his wealth, and he was able to move himself and his increasingly large family (he and his wife would end up having ten children) into an elegant turreted chalet at Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, where they were waited on by several servants and lived a life of luxury. Riding through the streets of Paris in his horse-drawn English carriage, dressed proudly in his latest bespoke three-piece suit, he would wave benignly at the crowds who would clap and cheer as he passed. This was what he had wanted, what he had earned, and he was loving every minute of it.

By 1895 he had outgrown the Moulin Rouge, formed his own touring theatre and started farting all over the world. It did not matter what country, what city, he was in; once he was on stage, bending down and blasting, the applause was much the same. He was Le Pétomane, and his flatulence never failed to fascinate.

Regardless of the unconventional nature of his act, he continued to prepare for each performance as meticulously as possible. He would self-administer an enema every afternoon and ingest carefully-measured amounts of charcoal to ensure that he could produce the right quantity and quality of gasses required for the exertions that lay ahead. He kept changing his routines, he kept pushing himself on, and he kept winning more admirers.

It took a world war to silence him. Once hostilities broke out in 1914, his engagements ended, and Le Pétomane pumped no more. He was, in truth, worn out.

Festering legal battles had contributed to his creeping sense of ennui. The manager of the Moulin Rouge, embittered by the loss of so big a star, had sued him for supposedly violating the terms of his old contract. He, in turn, sued the Moulin Rouge for attempting to replace him with a female Pétomane, who was actually a notorious con artist who was faking her farts via a pair of bellows secreted under her skirt.

His spirits sagged further when, of his four sons, one became a prisoner-of-war and two others were invalided out of the service. He felt he was living in a different, darker, world where farts were no longer funny.

Once the conflict ceased, therefore, he decided to turn his back on his famous alter-ego and return to being plain old Joseph Pujol, and running a couple of businesses - a bakery in Marseille and a biscuit factory in Toulon - with the assistance of his sons and daughters. He would live on until 1945, when, at the age of eighty-eight, he passed away peacefully, surrounded by his large and loving family.

Le Pétomane, on the other hand, had long since faded away. There were a few who still remembered him sufficiently well to joke, in all of the inevitable ways, about the evanescence of his stardom - it had 'gone with the wind', they laughed - but to the majority of French people, and those far further afield, the performer whose farts had sparked a phenomenon was now all but forgotten.

It would not be until 1967, when Jean Nohain and F. Caradec co-wrote his biography (translated into English as Le Pétomane, 1857-1945: a Tribute to the Unique Act Which Shook and Shattered the Moulin Rouge), that the legend of Le Pétomane started to live all over again. The book, if only for its apparent novelty value, was reviewed widely both in France and elsewhere, and the story began to spread.

The 1974 Mel Brooks movie Blazing Saddles would be something of a discreet homage to Le Pétomane, not only with the infamous fireside farting scene ('How 'bout some more beans, Mr Taggart?' 'I'd say you've had enough!'), but also via the name of one of the main characters: Governor William J. Lepetomane. There would be one or two more fleeting references in popular culture to the rediscovered master farter, although, for reasons of mainstream taste, the acknowledgements remained oblique.

This is when Galton and Simpson came in. 'We'd actually been vaguely aware of Le Pétomane for quite some time,' Ray Galton would tell me. 'He was one of those intriguing old characters that [comedy writers] heard bits and pieces about and talked about. Even if not all of the details were right, you'd hear the tales. Spike [Milligan] often talked about him, he found the whole idea really amusing. And we did, too. But when the book came out we read it - this was, I think, the very late sixties, early seventies - and really found out, for the first time, the full story, then it just stuck in our heads. We didn't know how we could do it, or if we'd be allowed to do it - it wasn't a conventional "thing", and there'd probably be obstructions, especially on television - but we kept thinking about it, on and off, for quite a while.'

It was 1977 when the pair of them decided that the time might finally be right. This was the era of punk rock, the dawning of the age of alternative comedy, the start of a new climate of iconoclasm and irreverence, and producers and distributors - more out of nervy opportunism than calm calculation - were suddenly far more open than before to consider 'edgy' and controversial subjects for the screen.

There was never any danger of Galton and Simpson doing anything merely, or mainly, for shock value. They were incapable of writing comedy without trying their best to invest real compassion into the text, and Le Pétomane appealed to them as much for the dignity of the performer as for the apparent indignity of his art. They knew, however, that the flatulism could not be fudged: the bottom line was that they were going to be writing about a Frenchman and his farts.

Aided by their agent, Tessa Le Bars, they secured the backing of a small production company - Legionnaire Films Limited, recently established by Peter Eton, a former producer of The Goon Show - in the autumn of 1977, and proceeded to plan the project. A rough draft of the screenplay came first, and then, early the following year, a director was chosen: Ian MacNaughton, a hugely experienced constructor of comedies (having previously overseen such ground-breaking television programmes as Spike Milligan's Q and Monty Python's Flying Circus), who had himself long been interested in exploring the peculiar story of Joseph Pujol.

The real challenge, however, was finding an actor who was able and willing to appear on screen as a man who was famous for farting. While this act was no longer seen as an on-screen taboo, it was still regarded as a risk-laden sound effect, and certainly not something to, so to speak, shove down people's throats. There was a marked difference between emitting the odd fart and embodying an odd farteur.

Sure enough, an unfortunate pattern soon presented itself when reactions started to come back about the script. David Niven, for example, responded enthusiastically, and expressed a firm interest in playing Le Pétomane, only to suddenly, and apologetically, drop out. Peter Sellers (who looked, when made up as Inspector Clouseau, eerily like Pujol) was, if anything, even keener on the starring role, and was full of suggestions as to how he might play it, before he, too, abruptly turned silent.

'Both of them had said they'd found it hysterically funny,' Ray Galton would recall. 'Both of them had really been all for it. Then both of them were advised by their agents not to get involved because it would be bad for their image, so that was that.'

The part was then offered to the very versatile character actor Ron Moody, whose reaction once again went from boiling hot to freezing cold in a matter of days after his panicked advisors had intervened. On reflection, he said, he felt the role, though funny, was just too undignified for him to take on.

Ian MacNaughton and Galton and Simpson were fully in agreement as to the next candidate to contact: Leonard Rossiter. The director had worked with him before on the pilot episode of Rising Damp (1974) and marvelled at his intensity and skill. The writers had been hugely impressed by him as an unnervingly edgy escaped convict in a memorable episode of Steptoe And Son called The Desperate Hours (1972), and had only recently been reunited with him for a one-off edition of The Galton & Simpson Playhouse entitled I Tell You It's Burt Reynolds (1977) - a gloriously brilliant half hour of increasingly febrile comedy that saw the actor play an annoying little man who becomes obsessed with proving that he correctly spied the big Hollywood star moonlighting in a routine episode of McMillan & Wife.

All three men were delighted, therefore, when Rossiter said yes. They knew that, to make the whole film work, they needed someone at its heart who would be completely committed and thoroughly believable, and that was what Rossiter, more than most, was capable of delivering.

'Leonard wasn't bothered about whether or not it might "spoil" his image,' Ray Galton would say. 'That wasn't what he was about at all. The only concern that he brought to a project was: "Is it going to be funny?" and "Is it going to be valid?" That was it. Only those two things. And luckily for us he decided it was going to be all right on both counts.'

With the team now in place, therefore, the prospects for the project looked exceptionally good. The end result, however, would prove to be something of a disappointment.

The movie - which lasts just thirty-three minutes - draws heavily on the Nohain and Caradec biography (sometimes verbatim), but it also shapes, edits and embellishes the story to suit the screen. A narrator (Ronald Fletcher) is used (and arguably over-used) intermittently throughout - allowing the movie, when it wants, to keep a certain distance between itself and its subject matter, rather like employing silver tongs to move something a bit messy from place to place - but, within the meatiest of the actual scenes, the subtle power of Rossiter's performance, and the odd wry little line from Galton and Simpson, ensures that at least a small degree of intimacy is still achieved.

The problem, however, is that it is not enough. With only half an hour in which to cover the life and the career, the film struggles to be more than merely a series of suggestive vignettes.

We are shown, for example, Pujol entertaining his fellow soldiers; Pujol quitting the bakery for the stage; Pujol assuming the persona of Le Petomane; Pujol enjoying his first flush of fame; and Pujol carrying on until the outbreak of the war. The sheer brevity and impersonality of each sequence does little to live up to the film's opening claim that this is going to be a 'sincere tribute' to 'a very real person and his remarkable talent'.

Leonard Rossiter often seems like a very real actor trapped in the cramped little boxes of a cartoon strip. It does not help that he (just like Niven, Sellers and Moody) is, in truth, rather too old for the part - the real Le Pétomane had been in his mid-thirties during his peak, whereas Rossiter was now in his early fifties - but, thanks to a combination of careful makeup, lighting and photography, this is far less of an issue than the fact that he has so little time, in any scene, to actually engage with his character. More often than not, he can do little more than try to convey a vague air of haughty aloofness before and after the intrusion of each electronically-dubbed parp. Rossiter's Pujol, as a consequence, seems little more than an appendage to his own anus, as ephemeral and anonymous as one of his odourless farts.

Similarly, Galton and Simpson's rare and special gift for dialogue is largely wasted because so much of the screen time is dominated by the po-faced narration, which plods along proffering such clichés as 'A star is born' and 'Pujol was ready for the big time' and 'What a success story!'. Without proper characters to write for, they can do little more than craft a few captions.

There is the odd decent exchange, such as Pujol's argument with his manager at the Moulin Rouge:

MANAGER: May I remind you that I have an exclusive contract?

PUJOL: There is nothing in any contract, sir, that can forbid a man from breaking wind when not on stage.

MANAGER: Your wind, sir, belongs to me!

PUJOL: My wind, sir, belongs to the WORLD! And I shall dispense it where I wish!

MANAGER: You're getting too big for your breeches! I shall sue you for breach of contract!

PUJOL: If you do that, sir, I shall merely turn off the gas!

Too often, however, the individuals take a distant second place to the emissions - and that is not a story, that is just a soundtrack.

The real story, surely, should have been more about the supreme - simultaneously risible and admirable - self-belief of Joseph Pujol, rather than merely the particular profession that he pursued. In this film, alas, one cannot see the faith for the farts.

It is a bit like reducing Citizen Kane to a brief montage of shots of him buying lots of things. Le Petomane is fixated on the farting, but it does not even seem sure what it - let alone us - should make of it all.

It is not a very funny film. It is not a very serious film. It is not a very insightful film. It seems too afraid to be very much of anything.

This is the great irony about the whole project. The film-makers lacked the conviction that their subject so clearly possessed. Le Pétomane was a success because Pujol did not have the slightest doubt that his audience would 'get it'. Le Pétomane is a failure because the film-makers did seem to harbour such doubts.

The man was bold. The movie is timid.

When, therefore, it reached the cinemas in May of 1979, the most common reaction it elicited was one of bemusement. Without the assistance of any kind of explanatory promotional campaign, it was left to the audience to work out what it was, and what it was meant to mean.

It did not help that, hopelessly incongruously, it appeared as the first part of a double bill alongside an American action thriller about New York gangs called The Warriors. Quite why a short film about a late-nineteenth century professional flatulist was deemed the ideal appetiser before the main attraction of a gritty and youth-oriented contemporary story about turf wars in and around Coney Island remains a mystery, but it hardly suggested a clear and coherent strategy for showcasing Le Pétomane.

Some viewers in the UK did not even get the chance to make their own minds up about the movie. It was banned in some cinemas after local complaints of bad taste.

Even these isolated controversies, however, failed to ignite any further interest in the film, which was overlooked almost entirely by the critics. Some may have turned their nose up at the subject matter, while others shrugged their shoulders at the execution, but, for one reason or another, Le Pétomane was left to sag down and shrivel up like an unwanted party balloon.

There would be a second cinematic release in 1982, when, much more sensibly, it was used as support for the film of the Amnesty International comic revue, The Secret Policeman's Other Ball, and it would also be shown on Channel 4 in 1987. It still failed, however, to arouse much public or critical interest, and, as the years went by, it slipped quietly away into obscurity.

Looked at again today (and it is currently being streamed for free on the BFI Player), it still seems rather a waste of the stellar comedy talents involved. For Leonard Rossiter, for example, it had promised to provide him with a fascinating contrast to the twitchily excitable Rigsby of Rising Damp, allowing him to show how equally expert he was at playing a restrained and self-disciplined character, but, in the end, it failed to afford him sufficient space in which to create a really believable character.

For Ian MacNaughton, it was about a theme that, though it appealed, never saw him sure as to how best he should shoot it. From the self-consciously clichéd vintage footage, rinky-dink piano playing and silent era title cards of the beginning, through to the knowingly poignant puffing-out of the pre-war footlights at the end, the director seemed caught between laughing at and with his subject. Perhaps with ninety minutes he could have crafted something clever and insightful and evocative, as well as intriguingly satirical, but with just over thirty minutes available he simply became a slave to the frantic pace.

As for Galton and Simpson, it may simply have been the right project at the wrong time, a noble failure about a novelty success. Although they had wanted to write about Le Pétomane for some years, when the chance to do so finally arrived it found them, perhaps, just a little too tired and jaded to do it, or themselves, justice.

It would be their last proper project as a partnership - Alan Simpson had been wanting to retire for several years, and he would do so once the film was completed - and the strangely impersonal nature of this final screenplay now feels almost as if they are writing themselves out of their own picture. The valediction is there, but the signatures are missing.

Fortunately, however, the feeling of deflation that comes with this film need only be fleeting. After reflecting on the often fascinating ways in which the format contrived to frustrate even talents as fine as these, we can always turn to all of the unqualified triumphs that made each one a comedy great.

The proper tribute to Joseph Pujol and Le Pétomane, on the other hand, remains to be envisioned. There have been a few other attempts, including a clumsy feature length commedia all'italiana biopic entitled Il Petomane (AKA Petomaniac, 1983) and a short low-budget American documentary called Le Pétomane: Fin de siècle fartiste (1998), but none that have found the right mix of art, empathy, critical distance and wit.

How much potential in Le Pétomane is there still waiting to be tapped? Well, to paraphrase the wonderful Galton and Simpson, it must be very nearly an arseful.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more