Can't touch this: Comedy and cancel culture

One of the things that history teaches us about comedy is that if you don't want to encourage it, then don't try to discourage it - you'll only make it worse; or better, depending on your standpoint. Nothing inspires the comic spirit more surely than the conviction designed to control it or even crush it.

People have been trying and failing to control comedy since ancient times. Aristophanes was already complaining about censorious 'busybodies' in the 5th Century BC, but he was also using them to bring more bite to his broadsides. There is no finer target for a humourist, he realised, than someone who lacks a sense of humour.

British history bulges with the blushing cheeks of those who, like Monty Python's condemnatory colonel, barged into comic contexts to demand that everyone stopped being silly. There has only ever been one consequence, ultimately, for such self-appointed arbiters of 'proper' conduct, and that has been their departure to the sound of loud and lasting laughter.

Take the men behind the 1737 Licensing Act (please!). They made the Lord Chamberlain the state censor and sought to stem the spread of satire in the theatre. What they actually achieved, in the long run, was to shine a light on just how arbitrary, antiquated and arrogant much of their and their successors' claims to the moral high ground actually were. The satirists would keep finding slyer ways to stick the knife in, while the censors kept shooting themselves in the foot.

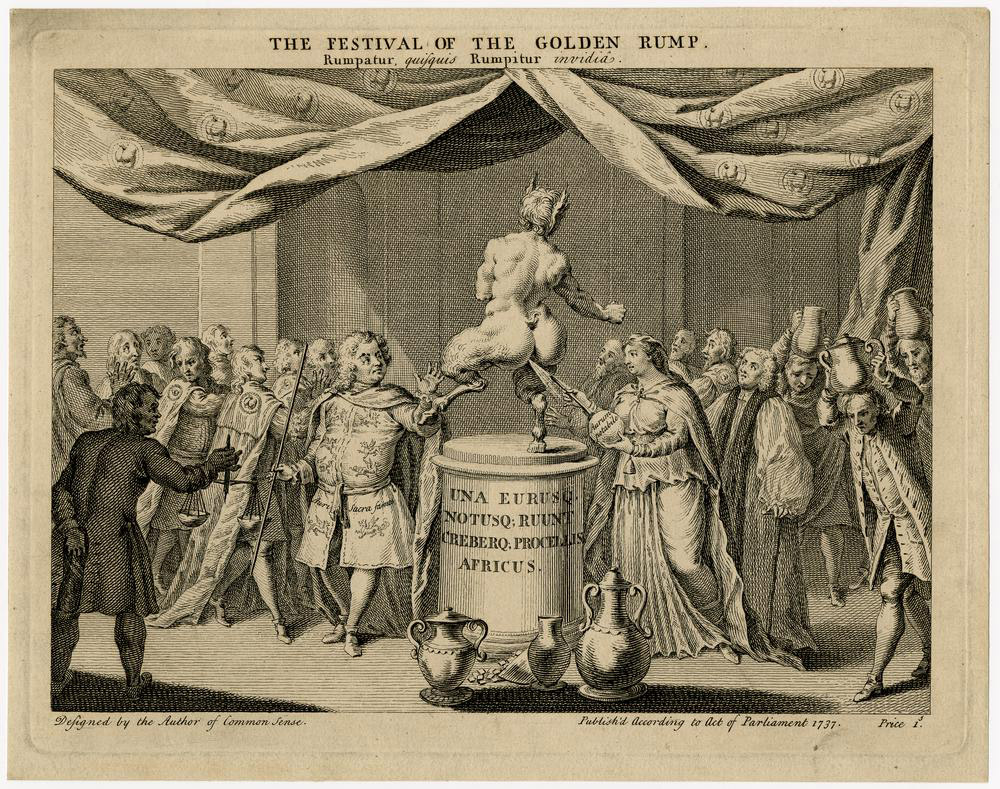

The clampdown had been at least partly provoked by a thus-far unperformed play of unknown authorship called The Golden Rump, which itself had been inspired by a scurrilous cartoon in which the cloven-footed owner of the eponymous posterior was obviously King George II, his pot-bellied Chief Magician unquestionably the then-First Lord of the Treasury Sir Robert Walpole, and the woman inserting 'a Golden Tube...with a large Bladder at the End' into her husband's gilded bottom was clearly Queen Caroline. There were suspicions even at the time that the play had actually been cooked-up by the much-criticised but deeply devious Walpole himself as an excuse to speed-up a shut-down, and, if so, it certainly worked: a majority in Parliament was sufficiently outraged to pass the legislation halting any dramatic performances that were considered to be seditious.

The office evolved in a predictable fashion, with the overtly political purview being quickly replaced in practice by a far more inclusive perspective that basically allowed the Lord Chancellor and his team to cover, cut and cancel whatever it was that they wished in the culture of their time. The list of verboten offences (as later spelled out by a parliamentary committee) included any play, passage or line deemed to be 'indecent'; any 'offensive personalities' or the representation 'in an invidious manner [of] a living person, or a person recently dead'; any disrespect 'to the sentiment of religious reverence'; any element 'calculated to conduce to crime and vice'; any aspect threatening 'to impair friendly relations with any Foreign Power'; and anything judged likely 'to cause a breach of the peace'.

The Lord Chancellor was empowered to arrive at and enforce his rulings without any limitation. He was obliged neither to explain his judgements, nor to have them referred to any court of appeal. He and his assistants - none of whom, incidentally, were required to have any recognised background or expertise in theatre, writing, criticism or ethics - were thus left to impose their dubious opinions on an unsuspecting nation whenever the urge occurred.

By the Victorian era the in-built absurdity of what George Bernard Shaw called this 'posse of numbskulls' was increasingly clear to see. A modest little play about Charles I, for example, was banned on the grounds of disrespect - which suggested that, while it was acceptable to decapitate a despotic monarch, it was a bit too much to mock them.

The subsequent century would be riddled with such stern but stupid rulings as the censorial thought processes started ping-ponging around like the twitching face of Chief Inspector Dreyfus after one more clash with Clouseau. The nation's authors and producers were, as a consequence, growing increasingly perplexed by the seemingly random recommendations that were being issued from the examining office:

For 'wind from a duck's behind', substitute 'wind from Mount Zion'.

Omit 'crap', substitute 'jazz'.

Alter 'turds'.

Omit 'balls of the Medici'; 'testicles of the Medici' would be acceptable.

We will allow the word 'pansy', but not the word 'bugger'.

Delete 'post-coital', substitute 'late evening'.

For 'the Vicar's got the clappers', substitute 'the Vicar's dropped a clanger'.

Omit 'piss off, piss off', substitute 'Shut your steaming gob'.

By the time of The Bed Sitting Room (1963) - a surreal farce-cum-satire, written by Spike Milligan and John Antrobus, set in the aftermath of an atomic war - the attempts by the Lord Chamberlain to tame the laughter were fast turning the office itself into a laughing stock. Its editorial orders for these two particular authors were promptly leaked to the producers of the BBC satirical programme That Was The Week That Was, and the whole procedure was held up for mass ridicule:

ACT 1

Page 1: Omit the name of the Prime Minister; no representation of his voice is allowed.

Page 16: Omit '...clockwork Virgin Mary made in Hong Kong, whistles the Twist'. Omit references to the Royal Family, the Queen's Christmas Message, and the Duke's shooting...

Page 21: The detergent song. Omit 'You'll get all the dirt off the tail of your shirt'. Substitute 'You'll get all the dirt off the front of your shirt'.

ACT II

Page 8: The mock priest must not wear a crucifix on his snorkel. It must be immediately made clear that the book the priest handles is not the Bible.

Page 10: Omit from 'We've just consummated our marriage' to and inclusive of 'a steaming hot summer's night'.

Page 13: Omit from 'In return they are willing...' to and inclusive of 'the Duke of Edinburgh is a wow with Greek dishes'. Substitute 'Hark ye! Hark ye! The Day of Judgement is at hand!'

ACT III

Pages 12-13: Omit the song 'Plastic Mac Man' and substitute 'Oh you dirty young devil, how dare you presume to wet the bed when the po's in the room. I'll wallop your bum with a dirty great broom when I get up in the morning'.

Page 14: Omit 'the perversions of the rubber'. Substitute 'the kreurpels and blinges of the rubber'. Omit the chamber pot under the bed.

A further blow to the now punch-drunk and decidedly jelly-legged institution was struck by the country's most eminent theatre critic, Kenneth Tynan (below), in his gloriously excoriating 1965 essay 'The Royal Smut-Hound'. Pointing out that the Lord Chamberlain should not be confused with the Lord Great Chamberlain - whose far more limited sphere of authority included supervising royal openings of Parliament and helping the monarch to dress on Coronation mornings - he proposed dubbing the former 'the Lord Small Chamberlain', and duly declared war on this 'repellent' canceller of culture.

First of all, he cited some of the literary giants (the list included Henry Fielding, Thomas Hardy, HG Wells, Joseph Conrad, Henry James, JM Barrie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) who had been discouraged from writing for the theatre because of the constraining ways of the country's state-sponsored critics. The mere existence of the Lord Chamberlain, he said, had always served as a 'baleful deterrent lurking on the threshold of creativity'.

He backed this up by quoting the anti-establishment playwright John Osborne, whose success in the mid-1950s with Look Back In Anger had made him a marked man as far as the censors were concerned, who sneered that he was behaving like a 'naughty little smart-alec small boy': 'It's the sheer humiliation that's bad for the artist. I know playwrights who almost seem to be living with the Lord Chamberlain - it's like an affair. There's a virgin period when you aren't aware of him, but eventually you can't avoid thinking of him while you're writing. He sits on your shoulder, like a terrible nanny.'

Tynan then started jabbing at the sweaty pink flesh of the here and now. Mocking any holder of the office - a sovereign-appointed figure who 'inhabits a limbo aloof from democracy, answerable only to his own hunches' - he ridiculed their pompous and pettifogging routine:

On royally embossed note-paper, producers all over the country are gravely informed that 'fart', 'tits', 'sod', 'sperm', 'arse', 'Jesus!', etc., are illicit expressions, and that 'the Lord Chamberlain cannot accept the word "screwed" in place of the word "shagged"'. It is something of a wonder that no one has lodged a complaint against His Lordship for corrupting and depraving the innocent secretaries to whom this spicy stuff is dictated; at the very least, the Post Office might intervene to prevent what looks to me like a flagrant misuse of the mails.

'The fundamental objection to censorship', Tynan went on to argue, 'is not that it is exercised against artists, but that it is exercised at all.'

It was therefore high time, he concluded, that the office be abolished, as Shaw had called for it to be abolished more than a half century before, 'root and branch, throwing the whole legal responsibility for plays on to the author and manager, precisely as the legal responsibility for a book is thrown on the author, the printer and the publisher'. Then, as if to further demonstrate the contempt he felt for such a logically unwarrantable authority, Tynan went promptly on to late night TV and quite deliberately said 'fuck' during a live debate.

The Lord Chamberlain's censorial duties were finally abolished in 1968, but a surprisingly high number of ordinary members of the public seemed eager, then as now, to assume the responsibility for treating their equals like inferiors. The first and most notorious of these ethical grand poohbahs was, of course, the devoutly Christian Warwickshire-raised and Shropshire-based schoolteacher Mary Whitehouse.

Whitehouse had not been able to stand most of what was screened by the BBC (ITV, for some bizarre reason, left her, like it does today's Daily Mail, far less distressed) since 1963, when, rather than reach for the 'off' switch, she decided, as rapidly as Thomas Hobbes warmed to despotism while speed-reading Euclid, that British television needed to be 'cleaned-up'.

She pinpointed the appointment of Hugh Carleton Greene (the brother of author Graham) as Director-General at the beginning of the 1960s as the primary cause of broadcasting's supposed moral 'collapse' into a condition of chronic turpitude. Here was a character, she decreed, who needed to be cancelled - and quickly.

Greene's professed ambition had been to 'open the windows and dissipate the ivory tower stuffiness which still clung to some parts of the BBC', as well as 'encourage enterprise and the taking of risks'. He later reflected: 'I wanted to make the BBC a place where talent of all sorts, however unconventional, was recognised and nurtured.' Many of those who had only recently emerged from a post-war era of rationing and regimentation thought this an admirable aim.

Whitehouse, however, interpreted it as a clarion call to anarchy and debauchery, and proceeded to attack Greene ('a divorced man', she noted tut-tuttingly, as well as, even more tut-tuttingly, 'unmarried and an unbeliever') for anything on the screen that she regarded as dubious in terms of taste. On 5th May 1964, she had announced, from the platform of Birmingham Town Hall, that she and her newly-formed 'Clean Up TV' acolytes - the blue pencil commander backed by the green ink brigade - were sending a telegram to the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, inviting them to give 'encouragement and support to our efforts to bring about a radical change in the policy of entertainers in general and the Governors of the British Broadcasting Corporation in particular', and added: 'In view of the terrifying increase in promiscuity and its attendant horrors we are desperately anxious to banish from our homes and theatres those who seek to demoralise and corrupt our young people'.

The following year, with further possessive pronouns flying out of her mouth like spittle, she decided - spurred on by the outrage caused by Tynan's use of the F-word on the BBC - that 'her' country and 'her' public required a more organised body with which to be busy, and so she formed the National Viewers' and Listeners' Association, whose role was to combat 'the propaganda of disbelief, doubt and dirt that the BBC projects into millions of homes through the television screen'. It would fight, she promised, to force the Corporation 'to make a radical change of policy and produce programmes which build character instead of destroying it, which encourage and sustain faith in God and bring Him back to the heart of the British family and national life'.

The BBC, however, was, in those days, made of sterner stuff, and so it continued to do its best to ignore her. On 17th November 1965, after being snubbed by the Director-General on several occasions, an enraged Whitehouse declared that 'nothing less than the removal of Sir Hugh Greene and those who support his policy will solve the present problem'. Greene, to his credit, resisted the temptation to say 'likewise', and merely turned a dignified deaf ear.

In the years that followed, however, she would remain a constant thorn in Greene's side, regularly contacting politicians to declare that, in her 'considered opinion', one programme or another urgently required to be reviewed and then condemned for propagating and stimulating promiscuity and/or undermining 'the moral, mental and physical health of the country'. So strong was her desire to shield the rest of the Great British Public from anything that might corrupt or confuse them that - in the most ill-conceived of all of her countless fog-horned fulminations - she even tried to block a repeat showing of Richard Dimbleby's extraordinarily moving and much-praised coverage of the liberation of the Belsen concentration camp on the grounds that such 'filth' was 'an awful intrusion' and 'very off-putting', as well as being 'bound to shock and offend'.

The greatest and most enduring cause of these noisy bouts of self-righteous indignation was Johnny Speight's working class family-at-war sitcom Till Death Us Do Part. When it started, in the summer of 1965, she was outraged immediately by the irreverence of the tone, the grittiness of the subject matter, the unapologetic directness of its language and the shameless and shouty outspokenness of its Cockney anti-hero, Alf Garnett. She therefore proceeded to denounce it repeatedly as the most egregious example so far of the BBC's shameless indulgence of 'moral laxity'.

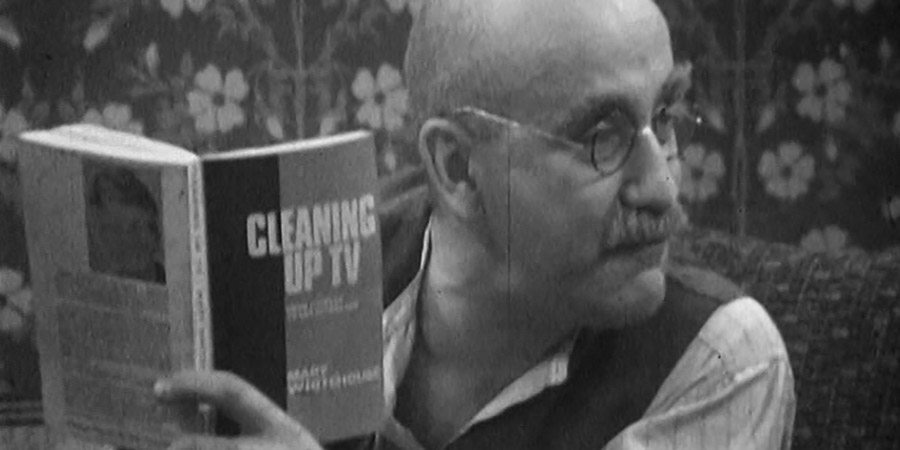

As a consequence, Whitehouse and Speight became each other's willing irritant. She would sit down with a ballpoint pen and a reporter's notepad and, as if chronicling a tense sporting event, dutifully count the number of swear words in every episode (one week she claimed to have registered as many as 103), while he had Alf Garnett read her newly-published Cleaning-Up TV book (usually when he was on the lavatory) and agree with every comment: 'That woman is concerned for the moral welfare of the country, ain't she...The moral fibre that's being rotted away by yer corrupt television...Y'see, that's where yer Mary Whitehouse is right, see, but what she's got to do, she ain't got to stop at cleaning up on TV, she's got to go on and clean up the whole country as well!'

Her inability to understand irony, and his addiction to it, would mean that they were destined to continue clashing throughout (and beyond) the rest of the decade - and both of them, predictably, would always feel that the other received far too much time, trouble and respect from the BBC.

When, for example, the Corporation, in a well-meant attempt to balance the integrity of one of its shows with the many threats and requests from Whitehouse and her fellow 'independent' watchdogs, tried to 'ration' Speight to twenty-five 'bloodies' per episode (or four fewer 'bloodies' for every two 'tits'), he became apoplectic with indignation: 'It's ridiculous', he complained. 'If bloody's a bad word, the more you say it, the more offensive it becomes'.

He had Alf sneer at the hypocrisy of it all - 'Look, if everybody in the country put two bob in a swear box every time they swore we'd pay off the national debt!' - but still the scripts were snipped. So notorious did this 'bloody' count become that, out of sympathy, Peter Cook wrote an inspired parody of Speight's regular meetings with his embattled producer to debate the matter, with Dudley Moore playing the angrily stuttering Speight and Cook his reluctantly censorious superior:

COOK: I think you'll agree with me that the BBC has been a pioneer in the field of controversial comedy. Look at the record: TW3, Steptoe, Till Death...

MOORE: What are you t-t-trying to say?

COOK: What I'm trying to say, Johnny, is that you've got twenty-seven bloodies in your script. We've led the way: I don't mind how many bloodies you have, that's fine by me...

MOORE: It reflects life, dunnit? I mean, I use 'bloody' the whole b-b-bloody time!

COOK: That's true. You're welcome to use it in life and in the script. The only thing that worries me about this script is the number of bums you have.

MOORE: So what's wrong with that? So I've got thirty bums in the script.

COOK: Thirty-one.

MOORE: Thirty-one, give or take a bum. The bums are all there for a dramatic cumulative effect. You're not going to tell me that bums don't exist?

COOK: No.

MOORE: I've got a bum, you've got a bum...

COOK: We've all got a bum, Johnny. I would not pretend that bums don't exist. But what I do ask you, Johnny, and I ask you this very seriously: does an ordinary English family sitting at home early in the evening want to have a barrage of thirty-one bums thrown in their faces in the privacy of their own living-room? I think not, I think not. I don't think we're ready yet to break through the bum-barrier.

MOORE: Don't give me that! Only two years ago, Kenneth Tynan said f-f-f-

COOK: I don't care what Kenneth Tynan said. That was a live, unscripted programme over which we had no control and I must tell you, Johnny, that it is very seldom indeed that we allow a bum to slip out before eleven o'clock in the evening.

MOORE: What miracle happens at eleven o'clock in the evening that takes the sting out of a bum?

COOK: Now then, I know it's illogical, you know it's illogical. It is illogical. But believe me, trust me: I believe in your bums. I'm going to fight tooth and nail to preserve your bums. I'll leave as many bums as I possibly can. Trust me, trust me. But there's one word that worries me even more than bum. And that is your colloquial use of a word for a lady's, er, chest.

MOORE: You mean my comedic use of the word t-t-t-...

In the end, in the sketch, an amicable agreement was reached:

MOORE: This script is more than just a comedy, it's a social document.

COOK: I realise that...

MOORE: A social document, in respect of the whole cosmic spectrum of...

COOK: I know this, Johnny. I realise how important these bums are to you.

MOORE: Not to mention the t-t-t...

COOK: Not to mention them if you possibly can. Now, Johnny, because I respect you as a writer of integrity and fire and passion, I'm willing to allow you all your twenty-seven bloodies. No questions asked.

MOORE: Right.

COOK: Furthermore, I'll let you have, let me see - this is more than I've done before - you can have seven bums. And because it's you, and only because it's you, Johnny, I'll allow you one, er, thingummy.

MOORE: Not even a pair?

COOK: I'm sorry, Johnny, I wish that I could.

MOORE: Look, I'll tell you what I'll do - I'll lose some bloodies if you give me an extra bum and another t-t-t...

COOK: Well, let's see, if you lost some bloodies it might be feasible. Why don't we make it seventeen bloodies, eight bums and a pair of, er, um, doodahs?

MOORE: So how many bloodies is that to a bum?

COOK: Um, ten bloodies to a bum, I'd say.

MOORE: Right. Now, I could lose ten bloodies in the pub sequence, that gives me an extra bum to play about with. I really think the scene in the launderette really cries out for another t-t-t...

COOK: Look, Johnny, if you feel you need another one of those in the launderette, I'll raise that. So that will give you, let's see, seven bloodies, nine bums, and three of the, er, the other word which you have.

MOORE: I'll raise you one bum.

COOK: You're really driving me into a corner here, Johnny. Mmm, tricky. Look: I know you, you know me: why should we let one bum stand between us? It's a deal!

MOORE: I'm glad we could discuss this in an adult fashion.

COOK: Thank you for being so co-operative. And I'll whip this script off to Sooty just as soon as I can.

MOORE: Well, bottoms up!

COOK: Cheers!

Speight came very quickly to consider Whitehouse as his very special bête noir, against whose rugged abuse he could keep on sharpening his biting wit. Every time, therefore, that she issued another moralistic edict, he responded with another satirical retort.

In one early episode, for example, one of Alf's drinking friends remarked that, after seeing Whitehouse complaining yet again about 'hardcore pornography' on TV, he had sat up all night in the hope of seeing some for himself, and was most disappointed when it failed to appear. Betraying a bewildering blindness to the barbs, however, Whitehouse proved incapable of critical self-reflection, and kept on cranking up the criticisms.

She did not object to Till Death merely because, in her opinion, it was 'vulgar' and 'blasphemous'. She also resented it because she deemed it 'unacceptably radical'. In an article she wrote for a popular tabloid of the time, she announced to the nation: 'One has long suspected that the BBC is being used for propaganda purposes, now it's clear. . . Last night we had a party political broadcast for the extreme Left-wing . . . And all in family viewing time. Last night children imbibed a good dose of anti-monarchy; anti-Ian Smith; anti-Wilson; anti-patriotism.'

Only once did Speight - after enduring one too many of these po-faced public attacks - make the mistake of being as humourless as she was, and thus played straight into her hands. On 17th January 1967, during an interview with BBC Radio 4's The World At One, he accused her of outrageous arrogance, hypocrisy and intolerance. Whitehouse - having listened intently to any mention of herself, as usual - responded the following day by issuing a writ against Speight and the BBC for libel: she claimed that Speight had 'implied' that she and her followers were actually 'fascists' who were concealing their true political beliefs under the cloak of a moral campaign. On 27th July, following some long but inconclusive legal discussions, the BBC and Speight agreed, reluctantly, to pay a 'suitable sum' to Whitehouse for the remarks that he had made.

He had learned his lesson. From this point on, he knew the best way to deal with someone like Whitehouse was to keep turning the comedy against her. The more that she railed against Garnett, therefore, the more that Speight made Garnett one of her most avid fans:

ALF: Listen, that woman, that Mary Whitehouse, is concerned for the moral fibres and the well-being of this beloved country!

MIKE: [Blows raspberry]

ALF: Never mind about that [blows raspberry]. It's being rotted away by your corrupt films and your telly! And your bloody BBC's the worst of the lot with that Top Of The Pops and the evil painted youths dressed up like girls, and-and that middle-aged peroxide albino clunk-click ponce they've got in charge of it!

ELSE: I like it.

ALF: Yeah, you bloody would, wouldn't you! And-and-and their seductive music, with-with their singing about...[gets embarrassed] men's fings an' that...

RITA: [Sarcastically] Oooh!

ALF: Driving the youth of the country to crime...and-and mugging [looks around] where's my bloody pipe gorn? - and-and bestialities and-and rape and-and b-bloody gypsies... an' refusing to go in to work...and-and-and-and bloody livin' off the dole and-and havin' no respect and mocking their elders - and calling me bloody skin-'ead!

Whitehouse would sit there, listening to this bigoted monster heaping praise upon her, and then, feeling confused and increasingly impotent, she would complain all over again. 'She was our biggest publicist', the show's star, Warren Mitchell, would say. 'Every time she protested to the BBC, we got another million viewers.'

She faded away, eventually, like ethical autocrats usually do, to be recalled occasionally only by those professional contrarians who know there is an article or two to be made from the principle that even a stopped clock is right twice a day. The more abiding thing about her, however, is all the laughter that Speight elicited from the incompetence of her many unsolicited interventions.

That is what tends to happen when comic writers are sure enough of themselves and their craft to satirise their would-be censors rather than merely complain about them. The pitchforks and torches may now have passed from the right of centre to the left of centre, but the rules of this sad game are still the same: they can shout much louder than you can, but they can't raise any laughs (and if they keep claiming to know what isn't funny, without being able to claim to know what is funny, then they're hardly well-equipped to cope with even the kindliest of comic inquisitions).

It is, of course, a fine thing to fight against intolerance and injustice, but first one must define and defend one's terms, and be prepared to consider carefully the alternative meanings and methods. There are far too many butterflies being broken upon wheels these days, and far too few broadcasters, journalists, promotors, pundits, politicians and other members of the public who are doing anything to stop it.

Comedians have a right - and sometimes a duty - to offend their audience, and their audiences have a right - and sometimes a duty - to be offended by comedians, but it is always for both parties to decide, individually, personally and privately, without any prodding or pressure from outside. Education, some people still need to understand, is not dictation. When the modus operandi of someone is to drag as many people as possible into a climate of fear, then the wise thing to do, the right thing to do, is to drag them into a climate of comedy.

Don't fight this on their terms. Fight this on yours.

It is revealingly ironic that those who now seek to claim liberalism as the source of their censoriousness are so quick to cancel one of the essential elements of that very intellectual complexion - namely, the humility that comes from the chronic recognition of one's own inexpungable fallibility. Once they do that (with the likes of Locke, Hume and Mill spinning away in their graves), then they deserve all the mockery, and more, that the satirists send their way, along with all of the laughter that follows.

As Oscar Wilde - one of those whose voice the self-appointed censors sought so cruelly to cancel - once wrote:

Selfishness is not living as one wishes to live, it is asking others to live as one wishes to live. And unselfishness is letting other people's lives alone, not interfering with them. Selfishness always aims at creating around it an absolute uniformity of type. Unselfishness recognises infinite variety of type as a delightful thing, accepts it, acquiesces in it, enjoys it. It is not selfish to think for oneself. A man who does not think for himself does not think at all. It is grossly selfish to require of one's neighbour that he should think in the same way, and hold the same opinions. Why should he? If he can think, he will probably think differently. If he cannot think, it is monstrous to require thought of any kind from him. A red rose is not selfish because it wants to be a red rose. It would be horribly selfish if it wanted all the other flowers in the garden to be both red and roses.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreThe Bed Sitting Room

In a vividly realised post-apocalyptic London, Mrs Ethel Shroake is crowned Queen and Lord Fortnum awaits his imminent transformation into a bed sitting roon. Meanwhile, seventeen-months pregnant Penelope and her parents have eaten all the chocolate bars on the Circle line, and leave the safety of their underground carriage to find her a husband and finally reclaim their baggage.

Richard Lester's sharply satirical end-of-the-world comedy features a who's who of British acting talent and a beautifully bittersweet, Goonish script by John Antrobus and Spike Milligan.

The Bed Sitting Room stars Spike Milligan, Harry Secombe, Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Arthur Lowe, Frank Thornton and Ralph Richardson.

First released: Monday 25th May 2009

- Released: Sunday 24th May 2009

- Distributor: BFI

- Region: All

- Discs: 1

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: BFIB1019

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: BFI

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: BFIVD834

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Till Death Us Do Part

Highly popular - and more than a little controversial - Johnny Speight's classic sitcom satirised the less acceptable aspects of conservative working-class culture and the yawning generation gap, creating a sea change in television comedy that influenced just about every sitcom that followed. As relevant today as when first transmitted, Speight's liberal attitude to comedy shone a light on some of the more unsavoury aspects of the national character to great effect.

Starring Warren Mitchell as highly opinionated, true-blue bigot Alf Garnett, Till Death Us Do Part sees him mouthing off on race, immigration, party politics and any other issues that take his fancy. His rantings meet fierce opposition in the form of his left-wing, Liverpudlian layabout son-in-law Mike, while liberal daughter Rita despairs and long-suffering wife Else occasionally wields a sharp put-down of her own.

Though all colour episodes exist, many early black and white episodes were wiped decades ago. The recent recovery of the episode Intolerance, alongside off-air audio recordings, allow this box set to include a complete run of the series from beginning to end.

First released: Monday 12th December 2016

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 8

- Minutes: 1,166

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: 7954597

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.