The bus stop: The post-fame fate of Bob Grant

It's been said that celebrity is a mask that eats into the face. It's also true that some roles become a cell in which the soul is left to rot.

One comic actor who faced the latter fate was Bob Grant. His role as the lecherous shop steward in the 1970s sitcom On The Buses was the one that made him, but also, alas, the one that broke him.

There were a couple of factors that combined to cue the sad side of that particular bargain. One concerned the prejudice of the profession, and the other the mentality of the man.

The prejudice, at the time, involved a fatalism about typecasting. If it was felt that an actor had become tied too tightly to his or her best-known role, few producers felt inclined to help them cut the connection and move on with their career.

The mentality, at the time, saw Bob Grant gradually give in to 'the grey drizzle of horror', as the author William Styron memorably called depression. When the work dried up, so did the hope, and he saw no future for himself.

We should pause, before exploring his story, to sound a note of caution against the threat of cliché. There was nothing inevitable about Grant's premature demise.

One of the laziest, and most irresponsible, myths propagated by pop psychologists is the claim that comedy serves as some kind of siren's call to the suicidal. 'Look at Tony Hancock', they say - as if his own sad decline was in some inscrutable way pre-programmed long before his happy rise to fame.

They then supplement the Hancock example with a ragbag of anecdotes about other comic figures who, at various points in their lives, were said to be depressed, as if a comedian whose outlook is not chronically sunny must be especially prone to dark thoughts, rather than merely an ordinary, reasonably sentient and sensitive, human being who experiences objective reasons for fear, worry or sadness.

Bob Grant was not blighted by mental illness. For most of his life he was a confident, positive and comparatively contented individual. It was cruel reality, and his response to it, that would eventually wear him down.

Robert St Clair Grant, as he was christened, was born on 14 April 1932 in Hammersmith, West London. His parents were comfortably middle-class - his father, Albert, was managing director of an asbestos company - and they ensured that their son was educated privately at Aldenham School in Elstree with a view to him pursuing a high-ranking business career.

Young Robert, however, had other ideas. Naturally outgoing, he became obsessed from an early age with the idea of being an actor, and, in spite of prolonged resistance from his anxious parents (who warned him repeatedly about the hazards of pursuing such a precarious - and, in their eyes, rather 'common' - profession), he left Aldenham determined to establish himself in the theatre.

He duly proceeded to train at RADA (with his father, reluctantly, paying his fees), did his National Service with the Royal Artillery, and then took any job going in London theatres. Desperate to learn about the system 'inside and out', he accepted every task offered him, from carpentry to touring management, so that, once he had achieved the status for which he was aiming, no one could question his convictions as to what was practicable as well as desirable.

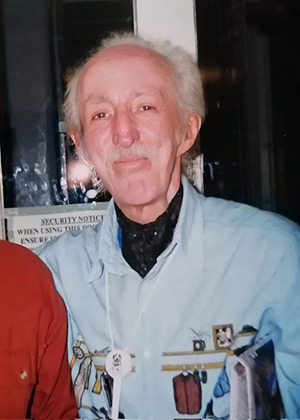

This was one of the aspects that made Bob Grant, as a personality, so distinctive. In a superficial sense, thanks to his extravagantly grand actorly accent (which made him sound rather like a raspy and revved-up Claude Rains) and taste for flamboyant attire (preferring colourful neckerchiefs to sober ties, and patterned jackets to standard suits), he seemed amiably laid-back and elegantly easy-going. When working, however, he was so driven and determined that, even from an early stage, he was unshakeably idealistic, ready to fight fiercely for whatever he felt was right for a role or a production.

'I had endless rows about anything', he later admitted. 'I think it is wrong to take everything for granted and never to question'.

'I almost got sacked from RADA many times', he added. 'I walked out because I didn't think we were learning the right things, and didn't agree with the kind of plays they made us do, or the way we were told to act parts'.

'I lost jobs as an actor', he continued, 'but for the right reasons. Had I stayed I would have had to conform to something that was wrong and I didn't believe in'.

He finally got to make his stage début, after a number of false starts and fights, as a priggish young man named Sydney in a production of Worm's Eye View at the Court Royal, Horsham, in 1952. Lasting for two weeks, it marked an inauspicious start to his professional career - 'I got £2 10s a week, which seemed a lot in those days, but the digs were £3 a week' - but, nonetheless, it was the breakthrough for which he had been waiting.

The following year he began a fifteen-month spell at Wycombe Rep, where he met and married (in 1954) his fellow actor Jean Hyett, and then moved on to another company in York. He returned to the capital in 1956, however, when he felt ready to audition for Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop in Stratford, east London.

A left-wing dramatic company committed to cultivating 'authentic' acting and exploring contemporary social themes, it was one of the liveliest, and most challenging, places for a budding performer to train and try to progress. The closest thing in London to the Actors Studio in New York, it was attracting a new generation of actors who craved more realism in the approach to their roles.

Grant, initially, was distinctly unimpressed with the company's base at the Theatre Royal. 'It was all very murky and downbeat', he would recall, 'just like some of the crummy little theatres I'd [already] been involved with, the kind where in the second week they tell you there's no money for salaries'.

His attitude at the audition, as a consequence, was so cooly aloof and half-hearted as to strike Littlewood as broodingly interesting, and, much to his surprise, she signed him up on the spot. 'Start Monday', she announced.

His first London appearance (billed as 'Robert Grant') soon followed in The Good Soldier Schweik, at the Duke of York's Theatre, and although, given his public school background and love of old-fashioned farces, he was hardly suited to Littlewood's gritty satirical style, he learned a great deal from her about craft and clarity in a performance. He also found someone else there who would become one of his lifelong friends: Stephen Lewis.

Lewis was working (not very well) as a bricklayer on the building site where Littlewood had taken her company to pick up practical insights for their next socially-engaged play. 'What you want to do', the foreman, pointing angrily at the gangling Lewis, told Littlewood as her troupe were preparing to depart, 'is to take this one with you. He ought to be a bloody actor!'

Littlewood was sufficiently intrigued as to do so, Lewis started learning his new trade, and Grant bonded more or less immediately with the somewhat eccentric and naturally amusing new recruit. Their lives and careers, from this point on, would repeatedly come together as both collaborators and co-performers.

It was during this period that Grant also formed a notable friendship with Jimmy Perry (the future creator of Dad's Army) and his wife Gilda, who were running the Palace Theatre in Watford. The couple would use Grant in a succession of productions over the next few years, beginning in 1958 with their staging of the pantomime Robinson Crusoe, and followed by such shows as the popular Whitehall farce Dry Rot (1959) and the musical-comedy Pretty as Paint (1960).

Grant also continued his association with Joan Littlewood at Stratford, appearing in the musical drama Ned Kelly (which starred Harry H. Corbett, Avis Bunnage and Brian Murphy, and for which Grant helped write several of the songs, supplying the lyrics to fellow actor Frank Coda's music). Subsequent Theatre Workshop contributions would include playing Kitely in Everyman in His Humour and Fred Jugg in Stephen Lewis's Sparrers Can't Sing (all three in 1960), and Mr Twigg in Big Soft Nellie (1961).

The critics were starting to take notice of his talent. 'Of Bob Grant', wrote one impressed observer, 'I am sure we will hear much more. [...] His personality vibrates with comic brilliance'. Others, noting his versatility, his gift for vivid characterisations and his ability to charm an audience, marked him out as 'one to watch'.

Grant moved swiftly to fulfil such confident predictions when, in 1962, he began what would turn out to be a lucrative two-year spell in the new Lionel Bart wartime-themed musical Blitz! Winning praise for his singing as well as his comic acting, his performances were commonly considered one of the highlights of the show.

As sometimes can happen as stardom grows, Grant's personal life suffered. His first marriage had already ended in divorce a few years earlier, and his second (to Christine Kemp in 1962) was in the process of going the same way, but he now claimed to be happier when concentrating on his career, being free to travel from one engagement to the next without any domestic entanglements, and open to every new opportunity whenever and wherever it arrived.

He followed his recent stage successes by further developing his songwriting ambitions, collaborating with the musician Laurie Holloway on the scores for several shows over the next few years, starting with a couple - the Brian Rix farce Don't Ask Me, Ask Dad and the seaside-themed comedy Instant Marriage - in 1964, as well as assisting Joan Littlewood with directing duties for The Marie Lloyd Story in 1967.

He was back acting in 1968 in the satirical play Mrs Wilson's Diary, first playing the infamously 'tired and emotional' Foreign Secretary George Brown and then (following the real-life Brown's own abrupt resignation from office) reappearing in several other roles. He reprised his performance as Brown the following year in a televised version for London Weekend Television, albeit after some enforced edits had been administered to reduce the potential offence.

Then came the sitcom On The Buses, created by Ronald Wolfe and Ronald Chesney, which was also produced by LWT. Set in and around a fictional London bus depot, it featured Reg Varney as driver Stan Butler and Grant as his conductor and next-door neighbour Jack Harper. Grant (who, somewhat ironically, had actually worked part-time as a bus driver during his days as a student at RADA, only to be sacked after crashing his vehicle) embraced the role of the scheming and saucy Cockney clippie with great relish, playing him as a free rider on public transport, a kind of in-house heckler, always quick to stand back and cackle at all the other characters.

His interactions with Stan and their shared nemesis, the miserable and meddlesome depot inspector Blakey (played by Grant's old Theatre Workshop friend and colleague Stephen Lewis) were particularly effective, forming the key comic triangle of the show (itself something of an homage to the old three-way exchanges popularised in the 1930s movies of Will Hay, Moore Marriott and Graham Moffatt). Blakey's threats ('If you're late taking that bus out...'), Stan's anxious reactions ('Look, it's not my fault...') and Jack's counter-threats ('As shop steward I am here to tell you....') combined to drive the second act of each episode.

Not every critic had welcomed the sitcom, with some finding its comedy 'clumsy and crude' and its characterisations 'lazily predictable', but many were happy to recommend it for its unpretentiousness and 'good clean' sense of fun. 'What we get', wrote one such reviewer of the opening episode, 'is good old-fashioned comedy with a few original touches here and there, enormous zest and some first-rate casting'.

Grant himself was by no means sure, initially, that the show would run beyond its opening series - indeed, a sign of his continuing openness to exploring other options came later that year when he and Stephen Lewis co-wrote and co-starred in a pilot of their own proposed sitcom, called The Jugg Brothers (about a pair of caretakers in a block of flats) for the BBC - but it did not take him long to realise that he was, at last, part of a major small screen success story. The ratings grew quickly, the press coverage expanded similarly swiftly, and another series was promptly commissioned.

On The Buses would go on to attract up to sixteen million viewers over seventy-four episodes (eleven of them written by Grant and Lewis) and two specials, as well as spawning three films for the cinema (the first one performing more successfully at the box office than any other British picture of that year), and was sold to thirty-eight other countries around the world. It made Grant, along with his fellow members of the cast, into a familiar TV celebrity, much-mimicked for his toothy grin and sandpapered way of speaking.

It was, in Grant's case, an unlikely way to find fame. He had not been the obvious choice to play a working-class character (indeed, he had tended to specialise, up to that point, in upper-class 'silly ass' types), nor, with looks that resembled a cross between Nosferatu and Tommy Trinder, was he a predictable pick to portray someone who was meant to be something of a low-rent Lothario, but, thanks to his understated but artful acting ability, and a contemporary Carry On culture that had managed to convince British audiences that someone with the looks of a Sid James could still have a strangely magnetic kind of sex appeal, he made the casting work.

What was equally impressive was the fact that he managed to keep the character likeable, even though, on paper, there was really very little about his personality to find endearing. Selfish, unreliable and untrustworthy, Jack Harper could easily have struck viewers as being far too rotten a rascal (there was always a suspicion that, if it suited him, he might well throw even his best mate Stan under the proverbial bus), but Grant gave him just enough charm to generate indulgent smiles rather than indignant sneers.

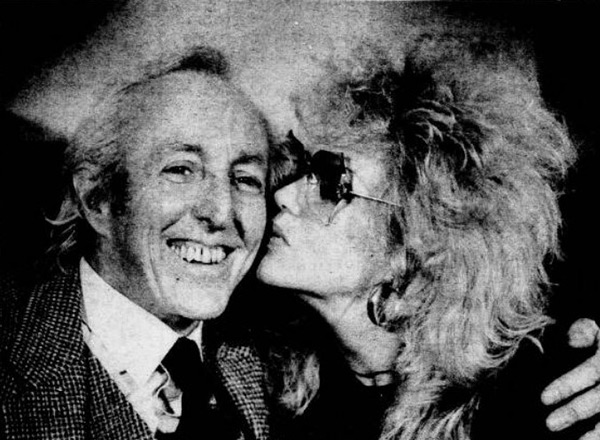

Indeed, he and the sitcom became so popular that when, in 1971, Grant married his third wife, Kim Benwell (whom, anticipating the Human League, he had met when she was working as a waitress in a cocktail bar - in her case at Paul Raymond's Revuebar in Soho), the couple were greeted by such a large crowd outside Caxton Hall Register Office in London that they had to walk to the reception and leave behind their hired Rolls-Royce along with the double-decker bus intended for all of their guests.

Grant was invited to open cinemas, supermarkets, community centres and, yes, bus stations all over the country. He was asked to advertise confectionary in Finland, Dutch transport in the Netherlands and alcohol in Australia. He was, according to certain news reports, 'mobbed' during some public appearances, after receiving 'the sort of reception normally reserved for pop singers'. Known to all as 'Bob [or Jack] from On The Buses,' he had become one of the most recognisable television stars of the time, and he loved every minute of his small screen fame.

When the show finally finished in the summer of 1973, Grant embarked on a tour of Australia (where the sitcom enjoyed an especially large and loyal following) in the popular farce No Sex Please, We're British, and then returned to the UK to take part in a number of new theatrical ventures. He would write and star in several of his own comic plays, including Package Honeymoon (1974), Darling Mr London (1975, in which he co-starred with David Jason) and No Room for Love (1977), as well as feature in numerous pantomimes and other classic and modern farces.

As far as offers of television work were concerned, however, Grant found himself, more often than not, passed over on the grounds that he was now considered to be typecast as 'Jack off of On The Buses'. Determined to push on in spite of such pigeonholing, he collaborated once again with Stephen Lewis on a pilot episode for a proposed sitcom, self-consciously distinct from On The Buses in both mood and milieu, called Shop. LWT bought the initial script, but then decided against filming it, and the pair found themselves right back where their old show had left them.

In 1975, switching strategies by embracing instead of resisting his still-dominant on-screen image, Grant scripted, with Anthony Marriott (the co-writer, with Alistair Foot, of No Sex Please, We're British), another pilot for a new sitcom, this time called Milk-O, in which he played an amorous milkman called Jim Wilkins and Anna Karen (who had been Olive in On The Buses) his harassed wife Rita. This did at least get filmed and broadcast by ATV during August of that year in its Comedy Premiere slot, but the majority of critics found it far too familiar and formulaic ('Milk-O comes over as little more than a poor attempt to re-work a worn-out seam', complained one), and the hoped-for series was never commissioned.

Greatly deflated, Grant went public in blaming the poor reception on the canned laughter that its producer had added to the recording. 'Terrible, wasn't it?' he was quoted as saying about its distracting effect. 'The only studio available was too small for an audience. We had to leave pauses after gags so laughs could be put in. It was murder to do'.

He was, by now, feeling increasingly fenced-in by his fame. When he had tried to go against type, such as in Shop, the TV companies had not been interested, but when he had decided to accept it, the critics had denounced him for not taking risks. Complaining therefore that he was damned if he did and damned if he didn't, he agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to end a deeply frustrating year reunited with Stephen Lewis in a pantomime - Jack and the Beanstalk - which made the most, both in its promotional material and its performances, of their association with On The Buses.

It did not bother Lewis, who had come to terms with his own typecasting to the point where he had already signed up happily to star in the On The Buses 'sequel', Don't Drink The Water, which saw Blakey retire to a flat in Spain. It did bother Grant, however, who felt simultaneously abandoned and entrapped by his old sitcom.

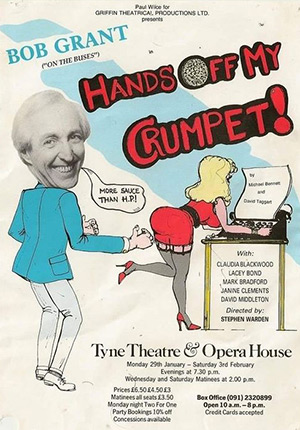

Unable to find a way back on to TV, he had no choice but to concentrate on his theatre work, and, for the next few years, he moved fairly steadily from one farce to the next, usually playing variations on his On The Buses character. With titles such as Hands Off My Crumpet!, these were innuendo-filled seaside postcard-style affairs through which Grant coasted with a growing sense of resentment.

Probably the nadir, as far as this particular sequence was concerned, was reached in 1980 with the stage version of the Mary Millington sex comedy Come Play With Me, which obliged Grant to share the stage with a number of nude or semi-nude female performers in a succession of farcical scenes. The production was dogged by poor reviews and moralistic complaints, as well as rebellions among the cast by women who were refusing to wear - or remove - some of the revealing costumes that were being forced upon them, and also by the failure of the management to ensure that all of their wages were paid. It closed prematurely when officials from the actors' union Equity reacted to the crisis by ordering the cast to quit the production with immediate effect.

Radio provided Grant with his sole source of artistic sustenance during this otherwise soul-sapping time, as the medium afforded him, occasionally, the much-needed opportunity to stretch himself both as an actor and writer. In 1977, for example, Radio 4 commissioned a number of short solo plays, written and performed by him, to be broadcast in one of its morning slots, exploring several distinct themes and styles. He also, during the following few years, got to narrate a novel by Wilkie Collins, contribute to an anthology-style series called Pen to Paper, take the lead role in a new adaptation of Don Quixote, and portray a cricket-loving Cockney detective inspector in Ken Whitmore's dark comic mystery The Red Telephone Box.

By the early 1980s, however, even the theatre work was starting to dry up. He toured mainly minor provincial theatres with his own version of the controversial sex revue from the end of the Sixties called Oh! Calcutta!, featuring several new sketches written by himself as well as the old exhibitions of nudity, but this strange theatrical melange bemused those expecting to see something akin to an On The Buses episode, as well as bored those hoping to see something as challenging as the original, and the show struggled to fill the venues.

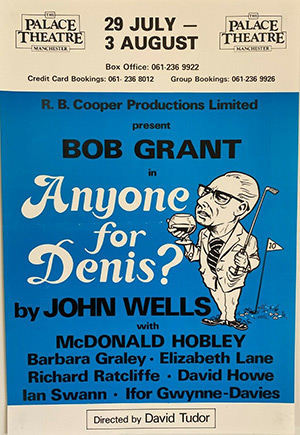

He fared considerably better in the 1982 touring version of John Wells' West End political farce Anyone for Denis, playing Denis Thatcher. The critics were very kind to him ('astonishingly good', one judged his performance), even though he had to endure being described, as if he had spent most of the past decade hidden away in a cave, as 'the long-faced chap from On The Buses'.

He then joined the cast of the Jeremy Lloyd/John Chapman comedy (set mainly underground in a deluxe nuclear shelter) called Keeping Down with the Jones'. Once again, his performances won him some of the best notices of a production that also featured the likes of Kenneth Connor, Nicholas Parsons and Dilys Watling.

After that, however, the good new offers seemed to elude him, and he was left to make do with various revivals of his own old farces, played out to smaller audiences, and more subdued reactions, than before. He would give upbeat interviews to the local press at each town that he visited, predicting that each touring production would run for many more months, only for the shows to close soon after.

There followed the longest period of inactivity he had experienced since his early days as an actor (it actually only lasted a few months, but clearly, in his eyes, it felt like an eternity). Having been accustomed, since his first flush of fame, to a lavish show business lifestyle, he now paced the polished wooden floors of his elegant Tudor cottage in the village of Waltham on the Wolds, near Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire, rang his agent repeatedly every day, and watched the bills keep landing on the door mat. Creatively, he felt suffocated; financially, he felt scared.

Putting on a brave face, he jumped at the chance of any kind of public exposure. He agreed, for example, to put back on his old On The Buses conductor's outfit and launch a pancake race at a local market, looking to all who gathered to watch him as though he didn't have a care in the world. It was one of the finest acting performances of his life, on the only stage he could now find.

His spirits were lifted suddenly at the end of 1986 when he managed to get hired (as one of the ugly sisters) for a low-budget Christmas production of Cinderella in Redhill, Surrey, at a newly opened theatre called The Harlequin. The show, which also featured his fellow Seventies sitcom star Sally Thomsett (from Man About The House), benefitted from the promotional push to boost the new venue, and although its run was relatively short by panto standards, it was generally well-received, and Grant's old self-confidence as a performer soon rushed back as the days went on.

Once it was over, however, there was an abrupt sense of anti-climax, the feelings of rejection returned with a vengeance, and he sank deep into his darkest-yet depression. 'For me', he later explained, 'the worst time was when the panto ended. To have a taste of what work could be like again, then to have that snatched away from me, was awful. All I could see was the empty months ahead, debts building up, no hope. I went into a black depression. I'd sit for hours with my head in my hands.

'I felt that I was in a black room with no window and no door, and the walls were coming in towards me. I just felt like screaming. I knew I had to get out, get away. I wanted to die, and I decided to top myself'.

Early on Thursday 22 January 1987, Grant, dressed all in grey and taking only a small suitcase and 'enough money to manage', thus slipped quietly away from his home and, after wandering aimlessly through Birmingham for most of the day, he wrote and posted letters to both his wife and his mother, and then decided to make his way up to Dublin by ferry. It is not known what specifically he did once he got there, other than deal with all the demons that were dogging him.

Having read a report of his unexplained absence in an Irish Sunday newspaper, he summoned the courage to call his wife the next day to apologise and explain, and then flew back to East Midlands Airport from Dublin on Tuesday morning and booked himself into a small hotel, where he sat alone in his room and tried as best he could to process his thoughts and emotions. The following afternoon, the local police - who had been investigating his disappearance for several days - visited him at his home to discuss what had happened. Dismissing some tabloid allegations that he had been guilty of wasting their time, they left without charging him, and announced that 'that is the end of the matter'.

At the end of the month, in a brave and heart-rending interview on Pamela Armstrong's BBC TV chat show, he tried his best to explain what had happened

I just knew that I had to get away. I didn't really know what I was going to do. I did consider suicide, I must say, that was one of the options. That's how low I'd got in my mind. I didn't really know what I was going to do, where I was going. I found myself in Dublin. A city I've always loved very much indeed. I find it a very calm and peaceful place. I love the Irish, I think they're wonderful people. [...] Inside me, I knew I had to find a haven, somewhere I could just be alone and work myself out.

Responding to the claims made by his own agent, Liam Dale, who, after announcing that he was severing all connections with the actor due to his 'unreasonable and unprofessional behaviour', had coldly alleged that he had probably merely staged the disappearance as an ill-judged publicity stunt, Grant snapped:

There's no way I'd do something like that for publicity. I've been through absolute hell in the last week. So has my wife, my mother, my friends. It's been a dreadful time. Frankly, I've been through I suppose what one would call a breakdown. [...] I just found the pressures too much to bear. The pressures of having been out of work for a long time, the pressure of looking at the future and seeing nothing coming up. I thought I cannot stand another period like I've gone through in the last year. I really cannot take it: 'The debts are mounting up, there's no future' - I was suicidal.

Grant went on to also refute his now-former agent's assertion that he had struggled to come to terms with his 'failure' to remain a fixture on TV: 'One always comes to terms with wherever one is in the business. I've done loads and loads of things since On The Buses [...] Of course, I enjoyed that period, I enjoyed the fame of being in a hit television series. That's fine. [But] I know that doesn't last forever. I don't expect it to. That doesn't worry me at all'.

It was not long after this appearance that a seemingly rejuvenated Grant announced that he had been taken on by a new agent, Joe Weston-Webb, who was confident that he could find his client more work. 'I am going back to the top', the actor insisted.

What he actually went back to, alas, was merely more of the same: uninspiring and poorly paid engagements, interspersed with long periods of inactivity and mounting anxiety. He started working for Weston-Webb's local agency, Unusual Attractions Limited, which specialised in finding and signing up undiscovered talent, and was given the responsibility of casting and directing a decidedly seedy-sounding touring production for the company entitled The Naughtiest Show in Town, but the production had to be scrapped after too few theatres consented to stage it.

He then collaborated with his old writing partner Anthony Marriott on yet another farce, Home is Where Your Clothes Are, but it failed to realise its hoped-for residency in the West End, and a plan to direct a pantomime in Leicester was dropped before work could be started. Things, once again, were starting to go wrong too often for Bob Grant.

He continued seeking work on the stage, swallowing his pride and visiting writers and producers in the hope of reminding them of his skill and versatility, but the opportunities remained rare. 'There is eighty-five per cent unemployment in the acting business', he said bitterly. 'When you have been at the top [the sense of rejection] is even rougher'.

Early in 1990, Griffin Theatrical Productions invited Grant to star in yet another revival of a farce he'd appeared in years before: Hands Off My Crumpet! Having not particularly enjoyed his last experience with a play (which advertised itself as 'cheekier than the naughtiest seaside postcard') that rarely strayed from the most cynical kind of sexism, he was far from excited at the prospect of reprising his performance as Godfrey Croker, the womanising managing-director of a crumpet factory, but, as he had no other options at the time, and it was set for a sixteen-week tour of some decent provincial theatres, he accepted.

Hands Off My Crumpet!, however, proved itself to be yet one more blow to his badly-dented ego. An instant flop with the critics, who damned it as 'foul', 'unfunny' and 'hopelessly antiquated', as well as with several feminist groups (who denounced Grant as 'ghastly' not only, it seems, for being himself, but also for allowing himself to be caricatured on the poster as poised to pinch someone's bottom), the tour was a disaster right from the start.

Trying hard to appear undeterred, the production struggled on to complete a week in Doncaster, a week in Stevenage, and then a week in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. The next scheduled week in Southsea, however, was scrapped due to poor ticket sales, and the remaining twelve dates were cancelled the following day when Griffin Theatrical Productions collapsed with debts of £67,000.

'It's just one of those things', Grant told reporters with a smile and a shrug after his last night on stage. Privately, however, he was despondent.

Then in March, quite out of the blue, salvation seemed to have finally arrived. Grant received the news that there were plans for a revival of On The Buses. Thrilled at the prospect of a return to TV, he joined the rest of the original cast to promote the project on the BBC talk show Wogan.

They were all clearly so excited to be reunited that they spoke over each other repeatedly, often rendering much of what anyone said more or less incomprehensible. Grant sat at the back, alongside his old friend Stephen Lewis, saying little, seeming happy just to be there, back with his colleagues, and back on the screen.

It was all going ahead, they told Terry Wogan, very soon. Except it wasn't, and it didn't.

No definitive explanation was ever given for the collapse of such a high-profile project (financial problems were probably the primary cause), but while its unexpected demise hit all of those involved hard, it left Grant, especially, feeling utterly shattered. After spending so many years resenting On The Buses for holding him back, the sitcom had re-entered his life promising to push his career forward, only, cruelly, to disappear once again, leaving him with a fresh sense of abandonment that was difficult for him to bear.

Withdrawing to his home in Waltham on the Wolds, and encouraged by his wife Kim to pause to talk things through, he tried to regain control over his troubled state of mind, blocking-out the memory of all the recent setbacks and summoning up more positive thoughts. It worked - at least for a while.

He did indeed seem to find a calming kind of distraction there. It came not only from taking in all of the sights of the pretty countryside nearby, but also from spending more time with his pet dog Hooray Henry.

With little work to take him away from home, Grant now fussed over the young Shih Tzu increasingly obsessively, treating him to specially-imported peanut butter, commissioning for him a special four-poster bed and dressing him up in various costumes, including a glittery Elvis Presley jumpsuit complete with a red-sequinned topper. Rather ironically, it was this devotion to the dog that ended up winning Grant one of his now extremely rare appearances on television, being filmed alongside his wife in an edition of an ITV pet show.

'We love Hooray Henry more than human beings and more than we love each other', he exclaimed somewhat clumsily. 'He loves us as well. He adores us'.

Beneath this show of sunny domestic contentment, however, Bob Grant was once again fighting his feelings of darkness. Sometimes resorting to accepting dubious offers of part-time telesales jobs, at thirty pounds an hour, to help pay the bills (only for the pay never to appear, and the parties ending up in court), he was searching desperately for more theatre work, but any engagements, when they did come, tended to be frustratingly short and superficial.

In the summer of 1995, during a rare run of work, he was found slumped unconscious in a car parked in a quiet area of Racton, near Chichester, where he had been due to appear later that day in a production of Hobson's Choice. Upon being discovered, he was rushed twenty miles away to a hospital in Gosport, where he was treated for carbon monoxide poisoning.

The theatre management, panicking at the prospect of 'negative' publicity, tried to cover-up what had happened by claiming that Grant had merely passed out from food poisoning, but few fell for such a fabrication, and the truth soon trickled down to the tabloids. The sad fact was that, feeling despondent, Grant had, this time, gone through with an attempt at suicide.

This time there would be no interviews or explanations. A broken man, he simply recuperated privately and quietly at home and then resumed the long and lonely search for work.

The engagements now were even fewer and far between. 1997 came and went with little happening for him except a couple more brief revivals of his own old plays. The following year, after a miserable winter, saw him secure a much-needed summer season at Devonshire Park Theatre in Eastbourne, alternating each week in two plays: the Agatha Christie whodunnit Murder is Easy, and the Ray Cooney farce Funny Money. He did not know it at the time, but these would turn out to be the last professional acting roles of his life.

Obliged soon after to downsize, Grant and his wife moved to The Corner Bungalow, Churchend, in the village of Twyning in Gloucestershire. Now entering his seventies, he no longer seemed to have sufficient strength to hide the sadness that was welling-up inside of him. Locals would later say that, on the rare occasions he ventured out, he walked around the nearby streets with his head always down and his face partly hidden by a scarf and cap, moving past other people like a ghost.

One day, staring once too often (as he had put it some sixteen years before) at the 'empty months ahead', Bob Grant finally gave up the fight. On 8 November 2003, his body was found inside a fume-filled car locked away in the darkness of his garage. He was seventy-one.

It was such a waste of an acting talent, and such a waste of a human life. What had made Bob Grant so depressed was what would make anyone depressed: loss of work, loss of money, loss of support, loss of hope. To censor him for how he responded is about as unfair as blaming a balloon for popping when pierced by a pin.

The memory of what he went through, and what he did, does not deserve to be appropriated by some mawkish myth about the innate sadness of clowns. Its proper message, surely, should be about the need for an industry to show more care, imagination and compassion, for a community to be more alert and attentive, and for those who feel abandoned to never stop seeking out the help, and the hope, that still ought to exist for them.

'It can happen to anyone', Bob Grant once said about his plight, and he was right. The best tribute to him would be for us to try harder to ensure that it happens to fewer and fewer people in future.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more