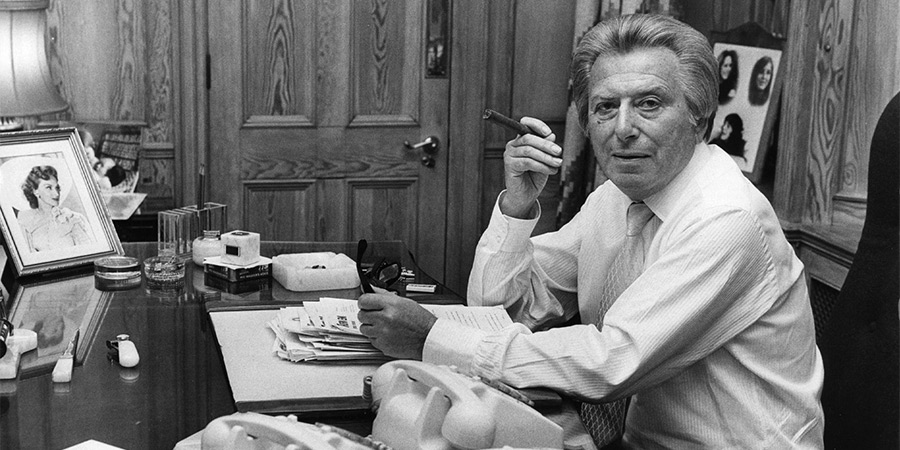

Comedy Tonight: Bernard Delfont's theatrical reign

Following on from the profiles of Jack Hylton, Val Parnell and Lew Grade, here is the fourth article in this occasional series within Comedy Chronicles in which Graham McCann looks at the main impresarios involved in comedy over the past century.

There was a time, roughly from the 1950s to the 1990s, when it seemed as though just about anything that was funny, as well as dramatic, that was going on inside a British theatre had arrived there courtesy of Bernard Delfont. He ran the Royal Variety Performance, he ruled the West End and he had a hand in most of what happened on the variety circuit from the city centres to the end of the piers.

Considered to be part of the so-called 'Gradopoly' that controlled most of the country's entertainment - with his younger brother Leslie Grade running the UK's biggest talent agency, and his older brother Lew Grade being one of the major players in British commercial television, and Delfont himself presiding over most of the top theatres - he was undoubtedly one of the giants of his era in the special sphere of show business. For so many years, the phrase 'Presented by Bernard Delfont' was as familiar to Britain's consumers of popular culture as was the image of Rank's man with the gong and the sound of the jingles on Radio One.

His story, like that of so many other impresarios of the era, is akin to the kind of inspirational fable that they loved to produce and promote: a tale of an underdog, an outsider, a self-made man who uses his wits to work his way right to the top of his chosen profession. As with all fables, it is inclined to romanticise a route that also featured some good fortune and a fair amount of family support, but there is still plenty of truth in the way that it has been told.

When Bernard Delfont, the self-styled 'impresario of pleasure', began his career, he, just like the show business world in which he worked, did not belong inside the Establishment. His triumph was not only to break into that elite, but also to take show business with him. For better and for worse, he helped make popular entertainment respectable.

Born Boris (but sometimes known as Barnet) Winogradsky on 5 September 1909 in Tokmak, Ukraine, he arrived with his family in England at the age of three, was brought up in Stepney's Brick Lane in the East End of London, and was educated at Rochelle Street elementary and Stepney Jewish School until leaving at the age of twelve. His movements over the next few years would largely mirror those of his older brother, Lew.

Bernie (as by now he was known) followed Lew into show business, becoming a professional dancer - never as good as his brother, but able enough to get by alongside a more accomplished partner. First he teamed up with Hal Monty, an old friend of his, and, on the advice of their agent, Sid Burns, started dancing together as 'The Delfont Boys'. He would keep the new surname when he moved on, in the early 1930s, to partner a Eurasian woman, called Judy Miller, as 'Delfont & Toko'.

Delfont & Toko, which started out as a conventional dance duo but evolved during the decade into one that also incorporated comic and acrobatic elements, became something of an international success, playing at decent venues all over Europe, South Africa and South America. By 1937, however, their style of dancing was fast falling out of fashion, and Delfont, nearing thirty, felt it was time to move on and try something else.

With his dancing days behind him, Bernie followed in brother Lew's footsteps once again by becoming an agent. Joining Lew's company, which he ran with Joe Collins, Delfont worked as an apprentice, learning the ropes as he toured the halls touting for business.

He only lasted a year with Grade and Collins, having already tired of being bossed around by his brother ('I have always wanted to do better than Lew - and he has always wanted to do better than me', he would later say of their sometimes fractious relationship. 'That is the drive we have. We are close friends but arch-rivals'), and late in 1938 he opened his own organisation, The Bernard Delfont Agency, in Queen's House, Leicester Square. The booking side of the business, however, never really appealed to him - he wanted to stand back and ponder the big picture, work directly with performers and directors, and play a more creative role in the productions themselves - so he ended up recruiting a specialist, Billy Marsh, to deal with the day-to-day running of the agency while he concentrated on contemplating what projects he wanted to promote.

It would prove an inspired partnership - one that would last for a quarter of a century - and it allowed Delfont to become a fully-fledged impresario. He would sign and promote stars; he would buy and control venues; and he would stage and showcase spectaculars. Step-by-step, over the course of the next decade or so, he updated the architecture of British entertainment.

He started by bringing in more international stars. He wanted productions that were less parochial and more worldly, and one of the ways he sought to achieve this was by persuading more and more big names from abroad to come and perform in Britain.

Chico Marx was one of the first to arrive, and he was followed by musical acts such as Martha Raye, Sophie Tucker, The Ink Spots, The Peters Sisters, Harry Richman and Lena Horne. Casting the net further afield, other stellar performers came in from the likes of France, China, Morocco, Switzerland, Argentina and Italy. Delfont also arranged two British and Irish tours for Laurel & Hardy, in 1947 and 1953-4, which also attracted a huge amount of publicity for himself in the process.

The coverage certainly niggled the country's top impresario of the time, Val Parnell, who felt (understandably) that Delfont was not only copying his own foreign policy but also moving quite aggressively into a territory he believed he had won the right to rule. The 'upstart', however, refused to back down, and a rivalry developed between them over the following few years that witnessed several stormy exchanges.

That competitive element also showed itself in Delfont's strategic pursuit of some of London's (and other cities') prime venues. He moved into theatrical management in the second half of the 1940s, acquiring a series of theatres in the West End and filling them with his own performers and productions ('You're never far', his newspaper ads declared, 'from a Bernard Delfont family show!'). In 1947, he took over the London Casino (known formerly, and latterly, as the Prince Edward Theatre) in Old Compton Street and started building it up as a viable commercial alternative to Parnell's highly-prized London Palladium, putting on similar 'top-drawer variety' shows featuring stars of the same kind of stature while advertising the venue as 'the new centre of international vaudeville'.

He also, in his pursuit of 'classiness' for his productions, started courting those directors who were known for their superior style and taste. Robert Nesbitt, who specialised in sumptuous spectaculars reminiscent of classic Parisian revues, but could also bring out all of the charm of more intimate kinds of performances, would remain at the top of his list of targets.

Such adventurousness was soon rewarded. There were big names in lights above his theatres, the seats were sold out every night and the interest in the press was immense.

After a few of these successful ventures, Parnell was the first to blink, summoning Delfont to his headquarters and telling the young pretender loftily that he was causing an embarrassment and demanding that he stop. 'Sure, I'll give up,' said Delfont. 'If you pay me £20,000 a year'. An apoplectic Parnell ended the meeting there and then and ordered Delfont to leave.

The battle raged on for a while, but the problem was that Parnell still had a much bigger, and far more established, power base, and he could afford to keep ramping up the wages for the big international stars (some of whom were supplied, ironically enough, by Lew Grade). Delfont ended up running out of money, and then he ran out of borrowed money, and then he ran out of business as far as the casino was concerned.

The loss of that particular battle, however, did not signal the end of the broader war. Ever the risk-taker, Delfont (who defined the role of impresario as 'part-accountant, part-lawyer, part-clairvoyant and part-master-builder', whose duty was to gauge public taste and 'carry on undaunted' in the face of competition, intimidation and crises), continued wheeling and dealing, managed to stay in business, kept his other theatres open, and continued to compete with Parnell - and he kept on scoring the odd big success.

A crucial victory occurred in 1949, when, right from under Parnell's nose, he managed to capture the UK rights to the original French company of the Folies Bergère. Parnell, as Delfont was well aware, had been eyeing this project for a long time as a perfect production for the Palladium, and, although he tried in public to affect an air of indifference, in private he was seething with anger and envy at his competitor's eye-catching coup.

Delfont, it appears, was gambling on provoking such a reaction, because he started encouraging the rumour that he was planning to stage the show at the Saville Theatre (now the site of the Odeon in Covent Garden), even though he knew it was too small and not really suitable for the home of such a lavish spectacular. Parnell, unable to resist the bait, eventually called Billy Marsh and said, 'Tell your friend Bernard Delfont that [the show] would be much better at the Hippodrome'.

Delfont was happy to agree, and the show went ahead as a co-production between himself and Parnell. That was the first stage in a two-step process that would see their rivalry metamorphose into a mutually beneficial alliance.

The second step revolved around Norman Wisdom. Delfont had taken on the comic actor when he was still relatively unknown, and built him up (via a couple of very successful spells at the casino) into one of the most popular performers of the period. Parnell, having more or less run out of fresh stars at the Palladium, was now desperate for someone new, and had been coveting Wisdom for some time.

When, at the start of 1954, he called Delfont to broker a deal, his rival impresario pounced on the chance to prise some power away from him. 'Bernard said, "You can't have [Wisdom] unless I do the show,"' Billy Marsh would later recall for the Hunter Davies book The Grades. 'Val said, "No; no one presents shows in my theatre". Bernard said, "No Bernard Delfont Presents, no deal". Val then said that if he did give Bernard the show, who would actually direct it? Bernard straight away said "Robert Nesbitt, of course". He hadn't got him fixed up at all, so he went straight to New York and saw him and arranged it. And so began twenty years of Bernie presenting Palladium shows'.

It was this change in their relationship that turned Parnell, effectively, into one of Delfont's patrons, providing the younger man with both the financial and political power to negotiate, amongst other things, the leases of a few more theatres. They moved on together, therefore, in a spirit of (relatively) peaceful co-existence, and, from the mid-Fifties onwards, managed between them most of the major metropolitan and provincial stages in Britain.

Delfont was not, however, just an accumulator of prestige properties. His ambition was also driven by a distinctive vision of contemporary leisure and entertainment.

In 1958, for example, he joined forces with the millionaire restauranteur Charles Forte and his new producer friend Robert Nesbitt to turn the old London Hippodrome, on the corner of Leicester Square and Charing Cross Road, into 'the most modem theatre restaurant in the world'. Providing three forms of entertainment under one roof - dining, dancing and stage shows - the newly-named The Talk of the Town boasted a seven-hundred-seater supper environment and two separate star-driven revues every night from 7.30pm to 2.30am. It was one of the most distinctive, imaginative and progressive additions to London's theatre landscape since before the last war - a bold and bright response to a deep-rooted need for some glamour, elegance and fun - and was an instant and huge success.

People marvelled at the mechanical stages, which ascended, descended and revolved at the flick of a switch, and the elegant décor, the two big resident orchestras, the large and bustling bars and smart-looking dining areas, the alluring dance troupes and the succession of famous names who graced Robert Nesbitt's cabaret shows. Seen as London's counterpart to the Paris Lido or Caesar's Palace in Las Vegas, it was a place to go to, a place to be seen at, a place to escape to and explore.

Delfont's addiction to supplying spectacular crowd-pleasing entertainment, combined with his craving for the seal of social approbation and acceptance, would make the next stage in his progression as an impresario all the more exciting and satisfying. In the same year as the launch of The Talk of the Town, he was appointed the producer of the Royal Variety Performance, with Robert Nesbitt as his director.

It was a huge personal triumph for a man whose family had fled to England from the horrors of the Russian pogroms, living initially in poverty in London, having to learn a new language from scratch, fight against home-grown antisemitism and scrap to survive in the harshest of social and material conditions. Boris Winogradsky was now Bernard Delfont, the outsider turned insider, and he relished every moment of his hard-won elevation in status.

It was something he wanted to share with the profession over which he now presided. His time in charge of the Royal Variety shows - which would last for twenty years - would see him take great care and pleasure in showcasing what he considered to be most worthy of admiration and respect in the world of popular entertainment.

This was thus now the main means whereby Delfont sought to 'legitimise' show business in the eyes of the haut monde. Everything about these annual affairs - the red carpet, the plush surroundings, the VIP guests, the evening dress, the black bowties and sparkling jewels, the long and glittery list of star performers - was made to adorn the idea of variety. He got the Queen Mother to meet his own mother. He got all the royals to watch The Beatles. He got countless comedians to remove the frowns from the crown.

He also helped revitalise the Royal Variety show itself, pursuing a policy that saw a shift of emphasis towards a younger generation of popular British performers, with a succession of up-and-coming musical acts and comedians getting invaluable exposure in each year's production. The appeal of the event was further extended by the decision to allow television cameras inside, with the first broadcast, in 1960, turning it into an instant ratings hit.

The medium of television, in general, would intrigue Delfont increasingly as the Fifties went on. Although, more like Jack Hylton than Val Parnell, the theatre remained his primary passion (and he continued expanding his property portfolio during this period), he only needed to reflect on the changing priorities of others in his family to realise that it would be wise to start exploiting the small screen at least as much as it was soon likely to start exploiting him. Commercial television was coming, variety was set to be a core element of its output, and he needed to protect and promote his businesses.

It seemed inevitable that ATV, with both his sometime-associate Val Parnell and his brother Lew Grade in charge, would provide Delfont with his entry into television, and he wasted no time in making it his second home. Soon after the launch of commercial TV, the name of Bernard Delfont became one of the best-known on the box. There was the Saturday evening variety showcase Bernard Delfont Presents (ATV, 1956-58), along with Bernard Delfont's Sunday Show (ATV, 1959-62), and countless other one-off or series spectaculars all broadcast under the Benard Delfont Presents banner.

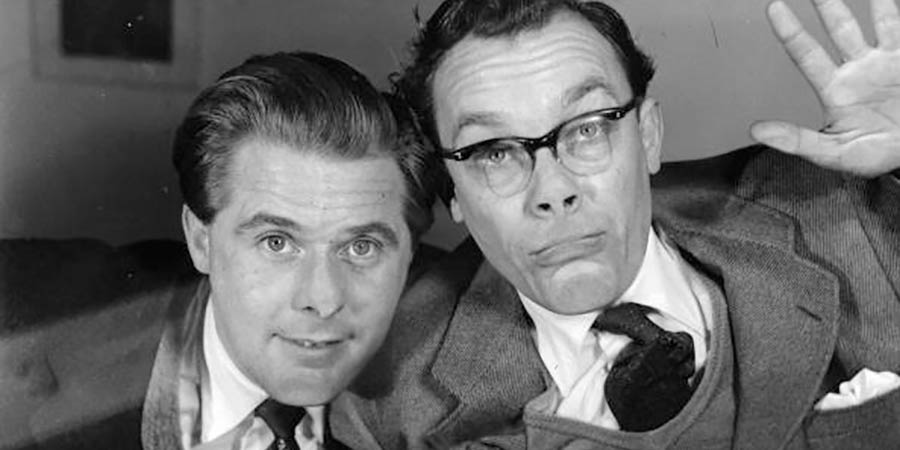

He also helped promote particular performers. His ability to draw on multiple means of placing and presenting entertainers was particularly evident in the role he played in advancing the career of Morecambe & Wise.

Eric & Ernie had endured a traumatic television debut back in 1954 with their critically-panned BBC series Running Wild. They had recovered some momentum since then as a stage act, and, later in the decade, were starting to seek a way back to the small screen. They regarded Delfont as the best man to help them realise that dream, and so they started writing to him pleading for a chance.

It worked. Billy Marsh, Delfont's deputy, signed them up to the agency, and he and Delfont started finding work for them in the company's theatres, clubs and tours, providing them with the time, space and support to try out new ideas and modernise their routines. While they were doing this, Delfont (along with his associate Val Parnell) also gave them plenty of guest spots in some of his television shows, building up the exposure as they came to relax more back in front of the cameras.

Then, in 1961, Delfont booked them to appear alongside Tommy Cooper in one of the many summer seasons he was running: Show Time, at the newly-built Princess Theatre, Torquay. With his and Billy Marsh's backing, they received a significant increase in positive media coverage during their residency there, as well as further expert advice from Delfont's theatrical team as to how best to keep improving their act.

This was followed, later the same year, with their debut series on ATV, which was billed as Bernard Delfont Presents Morecambe & Wise. It was the culmination of a very careful and methodical process managed by Delfont, and certainly proof of how synergistically interconnected his talent agency, theatre ownership and TV interests had become.

Other comic personalities who benefited from similar kinds of support during this period, on stage and screen, included Charlie Drake, Bruce Forsyth, Harry Secombe, Hylda Baker, Tony Hancock, Des O'Connor, Dickie Henderson, Billy Dainty, David Nixon, Norman Vaughan, Benny Hill, Bob Monkhouse, Jewel & Warriss and numerous others via the various Delfont-Parnell broadcasts.

A sign of Delfont's continuing sense of independence, however, was evident when, in 1962, he decided to end ATV's exclusive rights to televise the Royal Variety Performance. From this point on, he ruled, the broadcast rights to the show in the UK would be alternated between ITV and the BBC. 'I kicked up an alarming row', Lew Grade would say, 'but I had to take it on the chin'.

It was a shrewd decision by Delfont, having noted that, with more and more content in the theatrical presentation being determined by who, and what, was now popular on TV, he needed to ensure that his production could make full use of BBC as well as ITV artists and shows on its bill. Never simply the servant of the small screen, he was studying it in order to benefit from its potential.

It was the first of several steps that saw him gradually extending his media empire into other areas of entertainment right across Europe, North America, Australia and South Africa. He became, for example, a major shareholder of EMI in 1967, after it had acquired the Grade Organisation, and one of his achievements there was to buy up numerous key venues in his beloved Blackpool in order to transform the seaside resort over the next few years into the largest entertainment complex in the country.

He went on to serve as chairman and chief executive of the EMI Film and Theatre Corporation (from 1969 to 1980). Among his many significant actions during his time there was the overseeing of a £10 million programme to upgrade and modernise the company's cinema circuit as part of an effort to make 'cinema a place of glamour'; the appointment of the writer and director Bryan Forbes (and later Nat Cohen) as Head of Film Production to boost performance at the box office; the purchase of the music publishing division of Screen Gems from Columbia; his decision in the mid-1970s to pursue a radical strategy of investing in Hollywood cinema by producing 'American' movies financed by British money, thus reconfiguring the company as a 'supranational' rather than national movie producer; and his bold but ultimately unsuccessful bid to become a major Hollywood player by establishing Associated Film Distributors in 1979 - in partnership with his brother Lew Grade's Associated Communication Company - to distribute their companies' movies.

One of his few wrong moves during this period involved EMI pulling the plug on funding the Monty Python move Life Of Brian. It was actually more of a business than a moral objection on his part, with him reasoning that the probable controversy was likely outweigh the possible commercial appeal, but, when George Harrison stepped in to take over the financing of the film, and it went on to achieve great success, he took the loss with good grace.

Harrison bumped into Delfont soon after Life Of Brian opened. He was holding a copy of Variety that featured a headline about the film's excellent box office figures. Harrison waved the paper at Delfont and said, 'Thanks for backing out!' Delfont smiled, shook his hand and congratulated him on his enterprise.

Delfont, moving on, usually got most things right. He would also become chairman and chief executive of the entertainments section of Trusthouse Forte Leisure (1981-2), thus controlling such properties as the Blackpool Tower, three London theatres, the Leicester Square Empire ballroom and cinema, seven seaside piers, eighteen squash clubs, five ten-pin bowling clubs and nine discotheques. He was then chairman and chief executive of the First Leisure Corporation (1983-86), then executive chairman (1986-88), chairman (1988-92) and president (1988, 1992-94), overseeing, again among other things, the thorough refurbishment of several major entertainment centres.

He also entered into partnership with Cameron Mackintosh in 1991 to form Delfont Mackintosh Theatres Ltd. This brought him back more or less where he started, buying theatres and putting on shows. Although now in his eighties, his appetite for such creative and commercial adventures seemed unsated. 'I'm a grafter', he said, 'and grafters don't quit'.

He had always been tougher than his suave and well-tailored exterior suggested. Stress comes with the territory as far as impresarios are concerned, but Delfont had been obliged to endure more of it than most. Suffering from angina for most of his long career, he had learned to cope as calmly as possible with all of the crises that came his way.

One of his biggest anxieties each year, from the Fifties through to the Seventies, concerned the running time for the Royal Variety Performance. The Royal Family was never keen on the event going much over the two-and-a-half hour mark, but (thanks to individual performers, who were harder to control than a crowd of cats, getting over-excited and going far beyond their allotted times) it usually staggered on nearer to four hours - thus prompting much muttering and moaning in the royal box.

On one particularly painful occasion for Delfont, after the sprawling annual event had finally ended, he said to the Queen, 'If I may say so, Ma'am, that's a very beautiful dress you're wearing tonight'. To which she replied with a frown, 'Yes. I may be opening Parliament tomorrow in it, too!'

There were also isolated but intensely draining challenges with some of the stars he presented. The most notorious of these (since dramatized in the 2019 movie Judy) concerned the deeply-troubled Judy Garland, whom he booked for a series of comeback shows at The Talk of the Town in 1968.

Addicted to drink and drugs, she would sometimes be charming and sometimes antagonistic, getting standing ovations one night and things thrown at her the next, and it was never certain from one day to another whether she was actually well or willing enough to go out on stage and attempt a performance. 'Every night was agony', he would later say with a shudder, 'for Judy, for me, and for The Talk of the Town'.

Money was often the worst of his worries. Delfont's route to power had always been via a bumpier road than that taken by his brothers. People who knew him during his early years as an agent would remember him as being 'always broke', and there were certainly times when he had to head off the threat of bankruptcy.

Renée Stephen, his first secretary, would tell Hunter Davies that she often finished a week's work without any sign of her wages arriving: 'He'd spend Saturday or Sunday playing snooker, or cards, or on the dogs, and then when he got a win, he would come and pay me'.

There were just as precarious periods later on when he was running his theatres. Sometimes through over-generosity, sometimes through bad judgement, and sometimes plain bad luck, he would find himself in such a dire state materially that he would have to dodge the debt collectors, sleep on someone else's couch, downsize his house or (very reluctantly) borrow money from one, or both, of his brothers.

Being asked for 'a few quid' by the young Bernie Delfont was, at times during the Forties and Fifties, a fairly ordinary experience for many of his friends and colleagues. Loans were made, brown bags of cash would get pushed through his letterbox and sometimes even elaborate criss-crossing cheque scams would be required in order to save him being sucked down into financial oblivion.

What helped get him through such financial crises was a combination of great personal charm - 'He was a marvellous man to work for,' Renée Stephen would recall - and an indomitable Micawber-like optimism. No matter how bleak the circumstances might have seemed, he simply always expected that something positive would soon happen - and they did.

He had, and held, the classic impresario's nerve. Always the showman ('He has his name up in lights as often as his stars', sniped one critic), he shed the memory of each setback like a seasonal skin, and simply moved on to the next success.

He never admitted to having had failures. He merely conceded that some hits had not been as big as other hits. Like a proof-reader of his own text, he always knew how to improve a good tale.

One more of his strengths (sometimes overlooked or underrated by those who chronicled his career) was his readiness to listen to others. He had his own tastes and instincts, but he knew that, to appeal to the many, he needed to know what the many liked, and so he was always open to others' opinions.

It was his daughters, for example, who, in 1963, helped nudge him into booking one of the most memorable acts for that (or any) year's Royal Variety Performance. 'Do you know a band called The Beatles?' he asked them sceptically. 'Yes', they exclaimed, 'of course we do!' Surprised by the intensity of their response, he decided to act on their advice, and many jewels were then rattled on the big night.

It was this openness, along with plenty of courage, calmness, cunning and conviction, that made him one of the most important, and effective, of the country's impresarios.

Delfont, who died on 8 July 1994 at the age of eighty-four, was naturalised as a British citizen in 1961 (after four applications stretching back to 1937), knighted in 1974 and created a life peer (as Lord Delfont of Stepney) in 1976. 'I came to this country as a refugee', he once said, 'and I just want to pay back some of the things I've got out of it'. He had quite a life, and quite a career, and influenced British entertainment quite profoundly.

Some might say that, by making show business respectable, he also made it a little too safe, and there is probably some truth in that. It is hard to deny, nonetheless, that he also made it considerably easier for so many creative talents, from so many diverse backgrounds and artistic areas, to win the same degree of appreciation and admiration for their aims and achievements that the more traditional artists already enjoyed.

That is arguably the most important element in Delfont's rich and complex legacy. He presented the popular, and made people proud of it.

See also:

Jack Hylton profile

Val Parnell profile

Lew Grade profile

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more