Arrested developments: comedy out of context

The old story about the Yorkshireman, emerging grim-faced from the coal-dark doorway of a comedy club, reflecting on the experience by muttering, 'I suppose it were all reet if you like laffin',' certainly has a point. Humour does tend to rely on finding the right frame of mind to receive it.

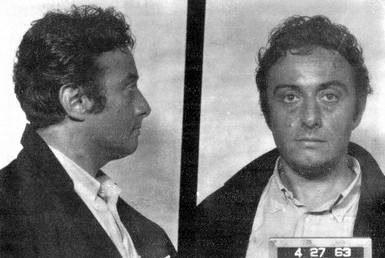

Take the sobering case of the great American stand-up Lenny Bruce, whose several obscenity trials during the early 1960s were such a source of fascination for the eminent American social theorist Erving Goffman (whose own work, incidentally, would later have a significant influence on the dramaturgical devices of Alan Bennett). A master on the effect of form over content, Goffman noted how a recording of Bruce's allegedly offensive material (some of it centring on the impact of the word 'cocksucker') initially caused the jury to start laughing.

'This is not a theatre and not a show,' snapped the grim-faced, gavel-banging judge, who then turned to all the other spectators in the crowded courtroom and snarled, 'I am going to admonish you to control yourselves in regard to any emotions you may feel.'

The warning was taken solemnly, Goffman reflected in his fine book Frame Analysis, 'and so, it developed, was the performance. No one laughed, and very few in the room showed the trace of a smile during the sampling of the humour of Lenny Bruce'.

That is how you kill a mood. Bruce's legal team managed to get him acquitted on this occasion, but the experience of sitting in court listening to his entire act play out to stony silence had been, he would later confess, one of the most demoralising of his whole career.

Goffman would term this process 'keying': 'the set of conventions by which a given activity, one already meaningful in terms of some primary framework, is transformed into something patterned on this activity but seen by the participants to be something quite else'.

Keying causes no great problems when most people present are in on it - such as when you go to a theatre to see someone act like a murderer, or a therapist guides someone through an exercise in role-playing, or an employee takes part in a training scenario in the workplace. Keying can start to be a problem, however, when not enough people know, or claim to know, what is really meant to be going on.

This is where comedians, more so than most, can stumble into trouble, because the context gets contentious once the comedy is taken off the stage. That is why the explanation, 'I was only joking,' though sincere, can sometimes fall on deaf ears, and the law proves itself in no mood for laughs.

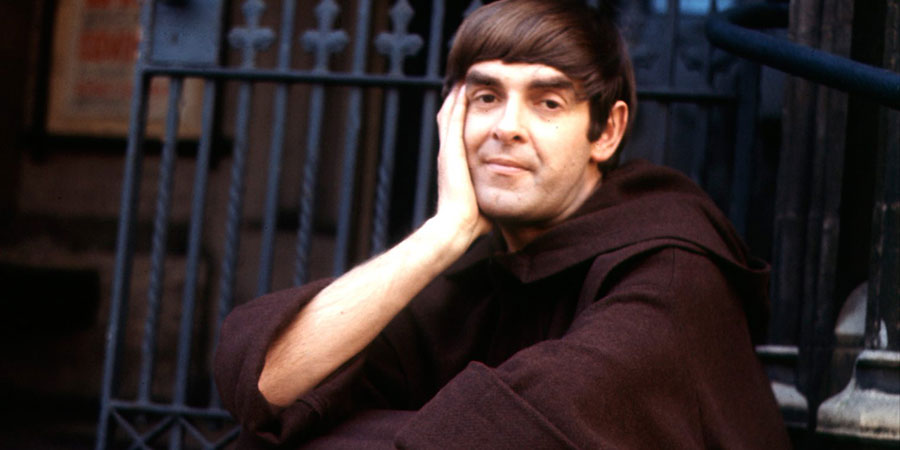

Perhaps one of the 'purest' examples of this, as far as comedy is concerned, is the case of Derek Nimmo, who in September 1969, through a clear clash of keys, ended up being arrested in Italy while dressed up as a monk. He was, at the time, enjoying considerable success back in Britain as the star of the BBC sitcom Oh Brother!.

A companion piece to his other religious comedy, All Gas And Gaiters, the show, in which he played the well-meaning but maladroit northern novice Brother Dominic, was regularly attracting an audience of more than twelve million, and, so far, had generally been taken in the spirit it had been intended, with only a handful of the country's more conservative Christians complaining, via very polite letters, about its light-hearted tone.

The BBC, indeed, had gone to great lengths to assure its viewers (and governors) that the sitcom was only poking affectionate fun at one individual character, rather than at religion, and/or monks, in general, and Derek Nimmo himself was well-known for his own, very sincere, devotion to the Anglican faith and his regular recordings for the Scripture Union (a number of vicars had even invited him to address their congregations in person, so impressed were they by the rare and heady combination of his celebrity status and in-depth scriptural knowledge, and when a recent Lambeth Conference was running he said that he had so many bishops asking him out to lunch that he ended up recuperating at a health spa).

When, therefore, Nimmo (accompanied by his wife and young family, his director Duncan Wood, and a sound and vision crew) flew off to Rome to film an insert for a forthcoming episode of the show (A Fool Returneth), neither he nor any of his colleagues expected any complications barring the odd minor technical glitch. To some of the Romans, however, they would be seen to be moving in most mysterious ways.

The reason for this very rare foreign location shoot was that, in the script, St Twytt, the erstwhile patron saint not only of fools and jesters but also of Brother Dominic's own Mountacres Priory, has been struck off the liturgical calendar 'on the grounds of non-existence'. Aggrieved by his abrupt demotion (and the loss of revenue they have been relying on from the related merchandise), Dominic and one of his superiors thus fly off to plead with the three adjudicating cardinals in the hope of changing their mind.

Arriving on the morning of Monday 15th September, the BBC team proceeded to film several rather playful shots around the city, including one in which Brother Dominic mistakes La Bocca della Verità for a letter box, without any incident, before they finally made their way to Vatican Hill. This is where the trouble began.

Nimmo, basking in the sunshine on the steps of St Peter's Basilica, was taking a short break between takes when he noticed a group of British tourists who were soaking up the sights. 'Mr Nimmo came over to chat to us,' Anna Pitt, a twenty-one-year-old drama student from Manchester, later told reporters. 'I recognised him immediately.' The always affable actor talked to Pitt and the other tourists about their trip, signed autographs, and then, when one man asked him to pose by hugging his daughter for a picture, he happily complied and lifted her off her feet in a joke embrace.

Unfortunately for Nimmo, a real Italian nun witnessed him doing so and, astonished and appalled that a monk would be behaving in such a manner with a woman in a mini skirt, scuttled off and summoned the Pontifical Gendarmeri, who in turn called the Carabinieri. Before the stunned actor (still dressed in his monk's habit) could work out what exactly was going on, they had arrested him, bundled him brusquely into a car and driven him straight off to the nearest questura, where he was stripped, handed a blanket and thrown into a cell.

'They grilled me pretty hard at the police station'. Nimmo would later say, adding that, no matter what stage and screen credits he recited, they flatly refused to believe his claim that he was merely an innocent and harmless actor. In fact, the interrogation lasted for more than two gruelling hours before they even allowed him to pause briefly for a drink of water in his cell.

'An Irish priest came in and recognised me and asked for my autograph,' he went on to say. 'But they still wouldn't let me go. I finally asked to see the British Ambassador.'

The BBC crew, by this time, had been alerted to the incident by a Daily Mirror journalist, Nimmo's fellow Liverpudlian Ken Irwin, who had been watching the shoot before moving on to cover the Verona TV Festival. Recalling the events in his memoir, Irwin would note that Duncan Wood - ever the professional - was most immediately concerned about protecting the footage they had filmed: 'Get everything packed into the vans,' he shouted, fearing imminent Papal confiscation, 'and let's get out of here!'.

Irwin, meanwhile, raced off to the Mirror's local office and, handing over the roll of film that his photographer (a French, Rome-based, freelancer who had also been arrested during the melee) had slipped furtively into his pocket, made sure that the news would be slapped straight on to the paper's front page the following morning. At about the same time, Duncan Wood, now that his precious footage was safely hidden away, called the BBC in London to alert them to his slightly less precious star's predicament.

The bosses back in Shepherd's Bush, upon hearing that one of their sitcom actors had been arrested outside the headquarters of the Roman Catholic Church, apparently snapped into action and hid. 'The BBC would have nothing to do with me,' Nimmo later complained. 'I was on my own.'

Eventually, someone managed to track down the British Ambassador, Sir Patrick Hancock. He was only a matter of weeks into the job, had only just returned to the Embassy after opening (of all things) a local Wimpy bar, and was understandably startled to discover the nature of the diplomatic incident that was now waiting for him on his desk. Adopting a suitably sober-looking expression, he rushed over to the police station, charmed all of the officers and - a full eight hours after the arrest - extracted the actor from his unhappy incarceration.

Nimmo left without receiving any apology, but, once it was realised that the news had been reported back in Britain, a spokesman for the Vatican announced that 'no further action would be taken'. The film crew had to make do with what footage was already in the can, and, breathing a collective sigh of relief, they all set off to London the following morning on the first available flight.

When Nimmo arrived back in England, walking through Heathrow carrying his young son Piers on his arm, he stuck his nose high up in the air and pretended to ignore all of the photographers who had gathered to snap him. On this occasion, however, none of them failed to get the joke, and they joined him soon after for a drink.

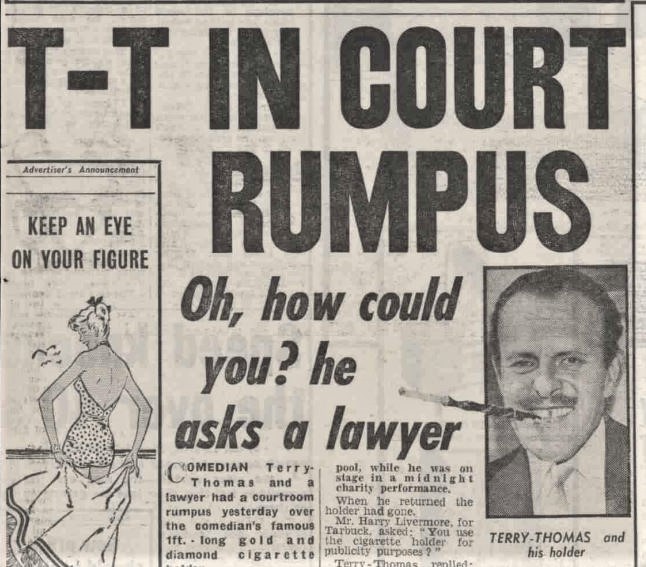

An example (one of many, in fact) of a more deliberate attempt at causing such confusion concerns the extracurricular comic exploits of Terry-Thomas, whose impromptu off-stage keyings frequently risked being misread by those who happened to witness them. The presence of the police, in particular, was often a catalyst for his context-curling antics.

'I don't think he took authority very gladly,' one of his co-stars, Ian Carmichael, would say:

There was an occasion in School For Scoundrels when we were on location in Hendon. It was a beautiful summer's day. And Terry had a blue Drop Head Jaguar at the time, and the hood was down, and he'd parked it on a kerb in the residential part of Hendon where obviously he shouldn't have parked it. We were standing by talking, and I suddenly saw two policemen coming along the other side of the street, and they were just going to cross over and talk to us. And I realised that what they were going to say was, 'What are you doing parked here - you're not allowed to park here'. And Terry had on the back seat of the car a toy Thompson sub-machine gun which you loaded with ping-pong balls. And he let these officers get within spitting distance of him - 'Oh, good morning, officers!' he said - and then, when they were within range, he suddenly bent down, picked this toy Thompson machine gun up from the back of the car and fired a whole volley, a burst, of these ping-pong balls at the policemen. And I've never seen two rozzers hit the deck so fast in all my life!

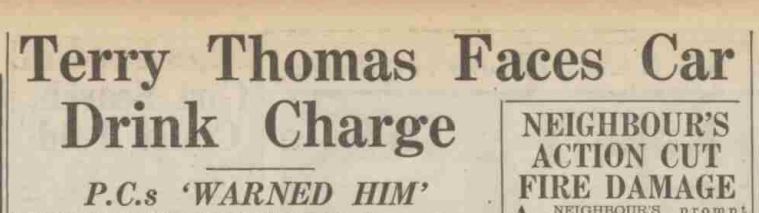

He got away with it on that occasion, because those particular policemen possessed a sense of humour, but had failed to do so when he was arrested late in 1957, on suspicion of being drunk and disorderly prior to driving.

Strolling out of London's Trocadero one evening, a fluffy white cat cradled casually in one arm, he had found two truculent-looking young constables standing by his latest sports car parked on the side of the road. Irritated by their presence (he had publicly dismissed a fine the previous year, for causing an obstruction in Holborn, as 'the fault of the police in allowing all the other cars to park in the street'), he proceeded to behave just like he would have done in one of his movies, peppering the air with witty put-downs before telling the pair not to 'be so bloody silly', then sliding into the car and attempting to ignore them and start up the engine. Rather than share in the sense of fun, however, the policemen pulled him back out and bundled him into a Black Maria bound for a police station in Savile Row.

Once inside the station, a doctor was summoned to conduct a routine sobriety test. The doctor - one James Gossip - duly arrived, placed some silver and copper coins amounting to the value of six shillings and ten pence on the station desk and invited T-T to count them. The still-playful star decided - 'very unwisely', he later acknowledged - to 'fool about', first offering to count the coins 'in Cockney' and then declaring ('in shockingly bad taste') that small change was 'just chicken-feed' and loudly counting out thirty-five pounds instead from a wad of notes in his wallet.

Unfortunately for T-T, in his haste to mock his accusers, he had actually slammed down six five-pound notes, not seven, on the station desk, thus arousing the doctor's suspicion that he was indeed dealing with someone somewhat the worse for wear from drink. T-T was then asked to walk across the room to the door and back: 'How would you like me to walk?' he inquired sarcastically of 'the old trout' Dr Gossip. 'Like a villain, a hero, like a poor man, or like a rich man?' The rattled doctor then pronounced him 'under the influence of alcohol' - to which T-T responded by snapping, 'And the same to you!' It had not gone at all well.

He appeared on remand at Bow Street Court on 16th January 1958, charged with 'driving a car while under the influence of drink to such an extent as to be incapable of having proper control over the vehicle'. Pleading 'Not Guilty', he elected to go to trial, and the case was eventually heard on the morning of Friday 14th March.

After having waited patiently out in the passage with what he would describe as 'some delightful whores', the cheerful-looking comic actor was eventually called into the court room, where, after protesting that he was a motorist who was in possession of a twenty-seven-year unblemished record, he went on to explain, several times, that it had all been a terribly unfortunate misunderstanding due to his succession of 'misread jokes'. The police doctor's responses proved to be not particularly helpful to either side, as, whenever he was asked to confirm or deny any of T-T's alleged remarks, his stock answer was a glumly non-committal: 'He may have done; he said such a lot'. As for the two police constables (who complained that they had 'been called names which are very unpleasant indeed'), their respective accounts were found to contain a number of inconsistencies, which had the defendant struggling not to pipe up with a triumphant 'I told you so!'.

He escaped eventually without censure after his current employers, MGM, provided the court with a convenient medical report (concerning the treatment he was receiving for lumbago) to support his claim that he had merely been the victim of an exceptionally arduous work schedule and some unusually powerful prescription drugs, and he was allowed to go back to work.

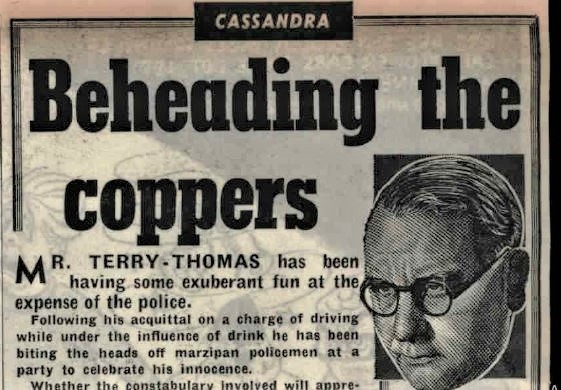

He celebrated this in typically provocative style, inviting reporters to join him and his friends for a party at the Colony Room Club in Soho, where much champagne was drunk and everyone bit the heads off specially-made 'marzipan coppers'. 'My dear chaps,' he told the slowly-swaying gentlemen of the press, 'don't get the wrong idea. I still like policemen. This is really just a gag. They're splendid fellows. Do a grand job. I just thought that this joke would fit in with the spirit of celebration. See what I mean? Good show!'

Emerging from the building quite a while later, in a rather more subdued mood, he could be overheard muttering about how 'the coppers must have it in for me', and vowing to recoup the money spent on eliciting those two precious words 'Not Guilty' by 'charging a fee in future for my charity appearances at police concerts'.

Coincidentally, or otherwise, he was stopped by another constable just a few weeks later and fined for allegedly ignoring a 'halt' sign while driving a car in Berkhamsted. 'Some people,' he said with a shake of the head, 'simply cannot take a joke.'

Ironically, Terry-Thomas would soon find himself on the receiving end of such a ruse - at least according to the other party - when he, too, was accused of failing to take a joke. It happened early in 1960, backstage during a midnight charity performance at the Odeon cinema on Liverpool's London Road.

T-T was hosting the event (which took place on 27th February and was staged in aid of the Liverpool branch of Guide Dogs for the Blind) at the behest of the local Labour MP Bessie Braddock, a big, bold and bright force of nature, sometimes nicknamed 'Battling Bessie', whom he adored ('She's the sort of a woman,' he declared, 'who could make you enjoy a lukewarm cup of tea on Crewe Station at three o'clock on a winter's morning').

Aside from the gap-toothed MC himself, it featured a wide range of other entertainers, including the actors Robert Morley, Dennis Kirtland and Sally Barnes, the singer Patricia Bredin, the Australian entertainer Lorrae Desmond, The Littlewood Songsters troupe, various members of The Ralph Reader Gang Show and a fair few local amateur acts.

T-T came off stage for the last time at 3:30am and, upon returning to his dressing room, discovered that someone had stolen his most expensive custom-made cigarette holder - a spectacularly flashy little item (valued at £2,000 at the time - about £50,000 in today's money) decorated with forty-two diamonds and a gold spiral band - from a table in the corner. There had, apparently, been a couple of other thefts, too: Patricia Bredin found that her fountain pen and £9 had been taken from her handbag, and Lorrae Desmond reported that £4 had gone from her coat pocket.

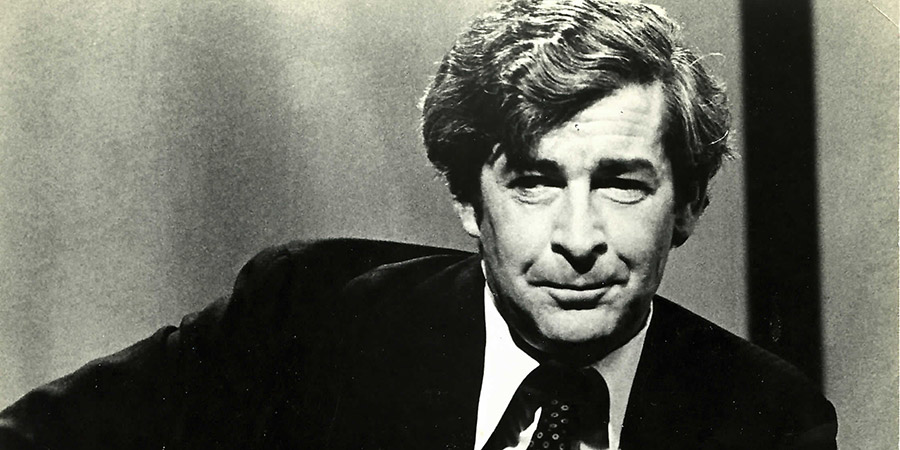

The police who arrived at the scene could not locate either the pen or the cash, but they did soon track down two of the diamonds in the possession of a twenty-eight-year-old local man named Alan David Williams - later described in court as an 'unemployed salesman' and 'variety artiste' from Stockville Road - and then found the other forty, along with gold parts of the holder, hidden inside a roll of carpet at the Queen's Drive home of a twenty-year-old unemployed comedian called James Joseph Tarbuck - a young man who, ironically enough, was himself destined for fame and a fair-sized fortune from the mid-1960s onwards as the mop-topped and gap-toothed stand-up comic Jimmy Tarbuck, one of the resident hosts of ITV's Sunday Night At The London Palladium.

Tarbuck was charged with theft, and Williams with being an accessory after the fact, and both were committed for trial at Liverpool Magistrates' Court in April 1960. It transpired at the trial that the desperately ambitious Tarbuck had sought out T-T on several occasions both before and during the course of the rambling midnight charity concert, asking him for the chance to make an appearance and perform some of his own material.

The distracted star, however, had replied to each of these repeated requests by 'pointing out to him that we had too many artistes already [and therefore] it would be madness to put anybody else on'. Feeling hugely frustrated (and depressed by the fact that he was beginning to slip deeper into debt), Tarbuck responded to the perceived snub by slipping into Terry-Thomas's unoccupied, and unlocked, dressing room and making off with the cigarette holder in what the defence claimed was nothing more or other than a young comic attempting to shake up an older one via a joke that got out of hand: 'a moment of pique rather than dishonest intent'.

After keeping the item hidden at home for a week, Tarbuck proceeded to break it up and then sold a couple of the diamonds to his fellow comic Williams for £3 in order to ease one or two of his most pressing financial problems. A number of other clandestine transactions, it was alleged, would follow in and around the Mossley Hill area of the city during the days that followed.

Once in court, both young men pleaded guilty and were duly sentenced (Tarbuck was placed on probation for two years, and Williams was given a twelve-month conditional discharge), but Terry-Thomas (who was described by court reporters as sporting 'an attractive suede waistcoat') was left feeling angry and somewhat demeaned - not so much by the theft (which he later dismissed as a 'silly jape' by a 'completely and utterly unknown' comedian), but more as a consequence of having had to endure what he considered to be the envious, resentful and cynically sniping remarks of certain barristers who were acting on behalf of the defence.

He knew that he had only recently 'put the backs up' of some members of the legal profession, yet again, following reports that he had been seen, during a break from playing a character impersonating a police inspector in the movie Make Mine Mink, roaming around the roads in Hampstead, still dressed in his uniform, stopping traffic and questioning pedestrians while himself impersonating an officer of the law. The complaints that this particular prank had provoked now caused him to suspect that, in some quarters, perhaps a bit of tit was coming in to counter a bit of tat.

The defence lawyer, Mr Harry Livermore (a local Establishment figure who was a former Lord Mayor of Liverpool), had particularly infuriated the star by accusing him repeatedly of inflating the value of the cigarette holder in order to create a 'publicity stunt'. 'How could you say such a thing?' shrieked an outraged T-T. 'Of course it is not! If it had been a publicity stunt surely it would have been easier to have had it made from gilt and glass!'

The performer eventually got the better of the barrister, tweaking a few raw nerves of his own - such as when, in response to the accusation that he had been 'silly and over-trusting' to have left such a highly-prized possession unattended, he looked Livermore coldly in the eye and observed, 'You have your collar on the wrong way round,' thus provoking the visibly rattled barrister to bark back, 'You will not insult me! I have no aspirations to be a clergyman - if you want to know!'.

T-T nonetheless remained resentful of all the supposed condescension he had encountered in the courtroom. As for the expensive cigarette holder: he was waving another one around as he left the building and passed by the waiting reporters, thus making sure that he was seen to live up to his motto - 'I shall not be cowed'.

Both the light and the dark arts of comic keying and re-keying would grow far more convoluted, but rather more methodical, in the decades that followed, from Andy Kaufman's chronic life-poking in the Seventies to Christopher Guest's docu-stylings during the Eighties and beyond, and on to the various contextual interventions staged more recently by the like of Sacha Baron Cohen, Simon Brodkin and Andrew Doyle. The consequence is that we are now far more key-conscious when it comes to their presence, if not always to their point.

We are also, alas, so much more easily distracted by the sheer multiplicity and immediacy of social media, and so prone to responding swiftly and somewhat rashly to their content, that those comics who choose to turn a key need to know a quick escape route to avoid, in these hyper-censorious times, being left locked inside. One needs to be almost as quick in explaining one's way out of a confusion as the audience was in leaping into it.

The much-missed Irish comedian Dave Allen, in this sense, might provide some inspiration from the past, in more of a pragmatic than a principled manner, when one reflects on how he wriggled out of some of the religious controversies that his comedy often caused. He would coax his critics into re-keying the content themselves.

On one such occasion, for example, he had filmed a short visual gag about dogma and desire. He later recalled:

The sketch basically was: a very old, decrepit priest - a bishop or a cardinal - sitting on his throne and holding the crozier; and a nun came in and genuflected in front of him and kissed the ring; and then a second nun came in and kissed the ring; then a third nun - a very beautiful little nun - came in, genuflected, and kissed the ring, and the crozier, just slowly, went into an erection. Which was a nice gag.

And then I was in a restaurant two days later, and this Irishman came over and said: 'You take the piss out of the Pope again and I'll have you. Wherever you are, I'll have you!' And I said: 'What are you talking about?' And he said: 'That thing with the crozier and the erection. Filthy! Disgusting!!' And I said: 'Well, actually, if you knew the clothing, it was the Archbishop of Canterbury'. And the man went: 'Oh...Ah...Ha-ha-ha - that's all right, then!'

Goffman called this quick thinking 'intention choreography', and, for those still keen on keying some comedy, but cautious about finding themselves entangled in someone else's frame of reference, it's an art well worth mastering. There are, after all, quite a few people around these days who simply don't seem to like laffin'.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreTerry-Thomas Collection - Comic Icons

Collection of six films featuring British comedy actor Terry-Thomas.

In Private's Progress (1956), upper-class twit Windrush (Ian Carmichael) causes military mayhem when he joins up in the army. An inept soldier, he unwittingly becomes involved in his high-ranking uncle's (Dennis Price) scam to appropriate some rather valuable spoils of war - a haul of German jewels.

The Boulting Brothers comedy Brothers In Law (1957) stars a host of British stars. Roger Thursby (Ian Carmichael) is an overly keen, newly-qualified barrister who rubs his fellow barristers up the wrong way. When he is thrown in at the deep-end, with a particularly hot-tempered judge (Miles Malleson) and tricky case, Thursby learns how to prove himself not only to the judge and fellow barristers but also to the public gallery.

In The Naked Truth (1957), Nigel Dennis (Dennis Price) is an unscrupulous tabloid publisher who is making himself rich by approaching celebrated personages with scandalous stories and offering not to print them for a certain fee. But some of his targets have had enough of this and are drawing up plans to do away with the rotten fellow. Terry-Thomas plays the aristocratic Lord Mayley, while Shirley Eaton plays model Melissa Right, and Peter Sellers is TV star Sonny McGregor.

In Too Many Crooks (1959), Fingers (George Cole) and his gang of crooks seem to be having a run of bad luck, as they keep botching one job after another. When they try to rob the wealthy philanderer Billy Gordon (Terry-Thomas) they manage to get things wrong once again and end up kidnapping his wife Lucy (Brenda Da Banzie) instead. Unfortunately, Billy is overjoyed to have his wife gone and makes no effort to pay the ransom, which makes Lucy mad and absolutely determined to have her revenge.

In School For Scoundrels (1960), Henry Palfrey (Ian Carmichael) is one of life's losers. Despised and disregarded at work, his prospective girlfriend April (Janette Scott) is whisked from under his nose by charming bounder Raymond Delauney (Terry-Thomas). In desperation, Henry enrols at Stephen Potter's (Alastair Sim) College of Lifemanship, where he gradually learns how to get one up on the other fellow.

Make Mine Mink (1960) is based on the stage play by Peter Coke. When Dame Beatrice Appleby (Athene Seyler) receives a fur coat from her ex-jailbird maid Lily (Billie Whitelaw) she can't help but suspect that it was stolen. In order to set things right she gathers together a team of local misfits, headed by the eccentric Major Rayne (Terry-Thomas), and draws up plans for a reverse-heist which will secretly put the mink back into the hands of its rightful owners. However, when the gang set out on their mission, they soon begin thinking that their talents could be put to other uses.

First released: Monday 14th May 2007

- Distributor: Optimum Home Entertainment

- Discs: 6

- Minutes: 545

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Bounder!: The Biography Of Terry-Thomas

With his sly little moustache, broad gap-toothed grin, garish waistcoats and ostentatious cigarette holder, Terry-Thomas was known as an absolute bounder, both on-screen and off. Graham McCann's hugely entertaining biography celebrates the life and career of a very English rascal.

Born in 1911 into an ordinary suburban family, Thomas Terry Hoar-Stevens set about transforming himself at a very early age into a dandy and a gadabout. But he did not put the finishing touches to his persona until the mid-1950s with his groundbreaking TV comedy series How Do You View?, a forerunner of The Goon Show and Monty Python's Flying Circus.

Terry-Thomas went on to carve out a long and lucrative career in America, appearing on TV alongside Judy Garland, Bing Crosby and Lucille Ball, and in Hollywood movies with Jack Lemmon, Rock Hudson and Doris Day. He became every American's idea of a mischievous English gent.

After a long battle with Parkinson's disease, he died in 1990 in comparative obscurity, but his influence lives on. Basil Brush was a polyester tribute to Terry-Thomas, and comedians including Vic Reeves and Paul Whitehouse hail T-T as a role model.

"Dandyism is the product of a bored society," D'Aurevilly observed. Terry-Thomas cocked a snook at the dull sobriety of post-war Britain with his sly humour. As he would say himself: "Good show!"

First published: Monday 1st September 2008

- Published: Friday 25th September 2009

- Publisher: Aurum Press

- Pages: 320

- Catalogue: 9781845134419

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Friday 25th September 2009

- Publisher: Aurum Press

- Download: 0.66mb

- Catalogue: 9781845137564

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Aurum Press

- Pages: 320

- Catalogue: 9781845133184

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Oh Brother!

The antics of Derek Nimmo's accident-prone Brother Dominic at Mountacres Priory regularly drew over twelve and a half million viewers to this classic BBC comedy.

This release includes all eight surviving episodes, which boast a distinguished cast including Sir Felix Aylmer as Father Anselm, the benign Prior, and Colin Gordon as Father Bernard, the less tolerant Master of Novices. The DVD includes a series guidebook.

First released: Monday 8th November 2004

- Distributor: DD Home Entertainment

- Region: 2

- Discs: 2

- Minutes: 239

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Best Of Dave Allen

A compilation of Dave Allen's favourite gags, routines and observations, selected from across the groundbreaking comedian's thirty years in showbusiness and including trenchant reflections on life, death, smoking and the nature of the Irish, all delivered from his trademark stool with a glass of whisky in hand.

First released: Monday 20th June 2005

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 93

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Essential Dave Allen

When Dave Allen passed away in March 2005, we lost a true comedy great. Sitting cross-legged on a high stool, whiskey in one hand, cigarette in the other, Dave Allen's exasperated commentaries on the absurdities of modern life struck a chord with millions of fans in Britain, Ireland and Australia for over four decades.

He was a compelling storyteller - able to spin shaggy dog stories out of the almost any subject, including the missing tip of his fourth finger of his left hand, for which he provided various unlikely explanations. But his gentle, laconic wit could also give way to ferocious attacks on the media, the state and, most famously, the Catholic Church. He was a unique talent - a comic who could make his audiences laugh, cry, and be shocked, all in one.

This official celebration of Dave Allen's comedy has been drawn together by Graham McCann - Britain's best-loved entertainment writer. It is a treasure trove of stories, stand-up routines, sketches, interviews and photos, which takes us on a journey from the cradle to the grave. It will delight Dave Allen's million of fans, old and new alike.

First published: Monday 7th November 2005

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 320

- Catalogue: 9780340899434

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 13th July 2006

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 320

- Catalogue: 9780340899458

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 25th September 2014

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Download: 1.67mb

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.