Are you talking to me? How Al Read held up a mirror to Britain

'It was as if I was selling myself along with the brisket, tongue and boiled ham.' This is hardly a line one expects to find in a conventional account of a comedian's coming of age, but then the man who said it was no conventional comedian. He was Al Read.

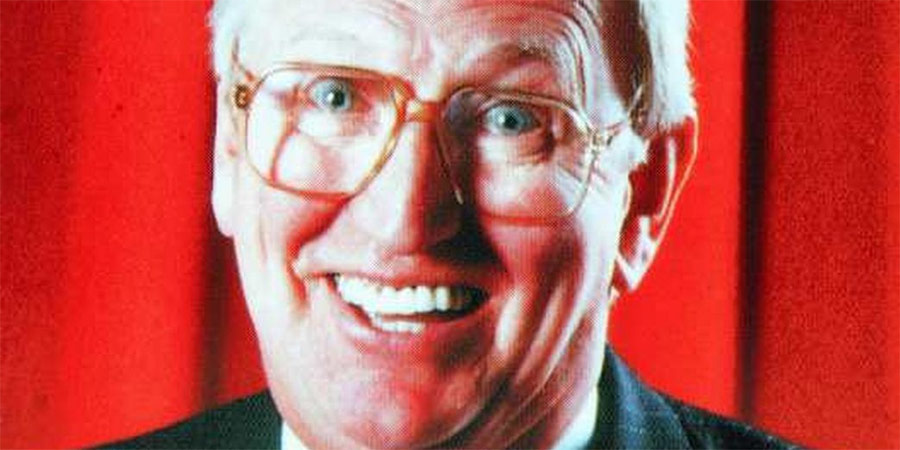

Al Read was an extraordinary comedian. He was not a joke teller. He was not a storyteller. He was a stand-up sitcom. He was a solo sketch show. He was a pioneering observational comic who, as his billing put it, 'introduced us to ourselves'.

His influence on British comedy was, and remains, immense. Tracing his multiple influences is like researching a particularly elaborate family tree: there are lines stretching back to him from the likes of Peter Kay, Billy Connolly, Dave Allen, Victoria Wood, Lenny Henry, Lee Evans, Les Dawson, Harry Enfield, Paul Whitehouse, Paul Merton, Michael McIntyre, John Sessions, Alan Bennett, The Likely Lads, The Royle Family, Last Of The Summer Wine, Keeping Up Appearances, One Foot In The Grave, the Shuttleworths, the Bradshaws, At Last The 1948 Show (especially its 'Four Yorkshiremen' sketch), The Two Ronnies and (until it lost its sense of humour) Coronation Street. In multiple ways and occasions, the connections between Al Read and contemporary British comedy keep coming together like the sound of two hands clapping.

Such an impact is all the more surprising given the fact that he only stepped into the spotlight when he was already in his forties. Before then he seemed destined to live out his life in the meat business rather than show business.

Born in Broughton, Salford, in 1909, he emerged into a world viewed largely through the prism of processed meat. His grandfather had been one of the first people in the country to produce canned meat, and by the age of eight he was already working part-time in the family firm of E. and H. Read Ltd at their processing plant in Kent Street. Leaving school at fifteen, he joined the firm full-time as a salesman, and proved such a success that he was made a director at twenty-three and, when his father eventually retired, he took over the running of the whole business.

Read would later encourage the romantic myth that his belated change of course into comedy came about entirely by chance, but, in reality, he spent most of his first four decades feeling frustrated by the lack of freedom to perform. At the age of eighteen he took himself off to Bolton to perform impressions of the French musical-comedy star Maurice Chevalier in the local clubs, only for his father, Harry, to find him and drag him back to Salford and resume his duties as a salesman.

It was not that Read Snr lacked a sense of humour - far from it. It was simply that he considered humour, like most other things in his life, as being best employed in the service of the meat business.

One of the most ingenious of his 'practical' gags was, as a Manchester United fan, to park the company's pie van illegally outside what in those days was the players' entrance at Old Trafford. He would then pass through the turnstiles with his son, and stand patiently in the Stretford End until the old tannoy finally crackled into life with the announcement: 'Attention, please: will the owner of Read's pie van move it from the players' entrance. Thank you'. Once this had happened a couple more times, he would turn to Al and say, 'You can't beat a bit of free publicity, son,' and then slip off to park elsewhere.

Al tried to follow suit, to some extent, using his natural gift for making people laugh to improve his sales technique, charming customers into buying far more meat products than they had planned. His longing to be a legitimate entertainer, however, would never go away, and over the next twenty years or so he seized on any opportunity to perform some routines at local clubs, pubs and hotels.

Meat made him a great deal of money. During the Second World War, he personally secured a lucrative contract with the NAAFI (the official trading organisation of Britain's armed forces) to supply two tonnes of luncheon sausage every week, and he also introduced a special canned meal of a finger of meat encased in mashed potato that became known as the 'Frax Fratter' - which not only became the butt of many comics' jokes but also made Read a fortune.

It also gave him the material security that allowed him to start taking his dreams a little more seriously. This would see him lead what was, in effect, something of a double life.

By day he remained Alfred Read, the model of a wealthy northern businessman, sporting an array of smart bespoke suits, brilliantined hair, puffing on a pipe and affecting a somewhat 'posher' form of a Lancashire accent than he previously used to have. In the evenings, however, if he was able to do an after-dinner speech somewhere (such as at the annual dinner-dance of the Grocers' Society), he would be there as Al Read, and launch into all kinds of characterisations, from drunks to cheeky children, and entertain the crowd.

Once he had moved home to Lytham St Annes, he also spent a great deal of his leisure time at the local golf club, St Annes Old Links, which was a magnet for countless show business figures who were playing summer seasons in Blackpool. It was there, after the war, that he started trying to acquire some useful connections as he looked to take a step into a second profession, and he even succeeded in selling the odd idea to comedians of the stature of Sid Field.

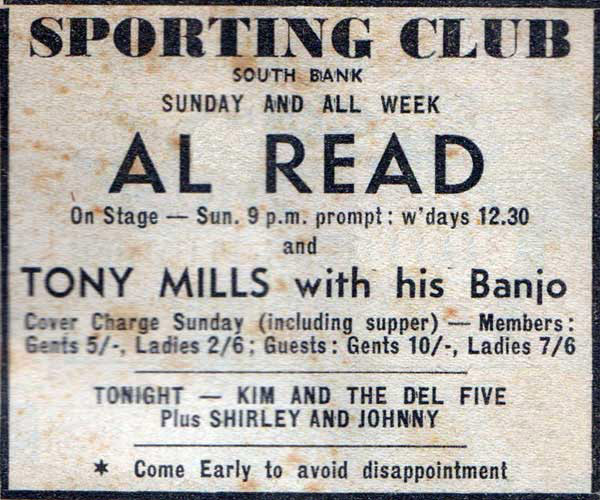

In 1948, he had become so eager to get himself noticed that he approached a Blackpool producer called Jack Taylor and offered to pay him for a spot in a Sunday concert being staged on the South Pier. Taylor, amused by his unusual request, agreed, but, thanks to an ill-timed attack of nerves, the appearance failed to elicit a positive response.

Feeling badly deflated, he withdrew back into the meat business for a while to lick his wounds ('The sausages seemed like old friends'), and then dabbled briefly in boxing promotion before resolving to start performing again. There followed a few amateur, and one or two semi-professional, engagements, but there were still no real signs that he was making any kind of progress.

It was only two years later, in February 1950, that he finally got his break, and, ironically, it happened because of, rather than in spite of, his day job. He was hosting an event at the Queen's Hotel in Manchester, wining and dining some of the biggest buyers of meat pies and sausages in the north of England, and, true to form, he could not resist finishing the evening off by performing one of his most polished party pieces.

As usual, it was a routine drawn from real life. It concerned the night when he returned home from the meat factory and, before he could pull his boots off and sit down to relax, his wife started unloading all of her latest problems on to him:

WIFE: What are we going to do about my mother?

AL: Er...your mother, luv? How d'you mean?

WIFE: My mother's coming a week on Friday and she's not sleeping in that little bedroom in the state it's in. I feel ashamed. It needs decorating.

AL: Well, I'll decorate it, luv. It's only a little room, I'll have it done in no time.

WIFE: Oh, we've seen your decorating before! You did our bedroom and what happened? You ran out of wallpaper! We've had to have that wardrobe in front of the bit you never finished ever since! So you needn't bother. I've rung up a decorator and he's coming to give you an estimate in half an hour.

He went on to recount how the decorator, when he arrived, turned out to be a brusque, barrel-chested, booming-voiced 'Johnny Know-All' type who unnerved with his every word:

DECORATOR: Ard-yer-do!

AL: Oh...er...H-How d'you do.

DECORATOR: I understand you want your house decorating right through?

AL: Oh, er, n-no, not through. It's just the little bedroom, really...

DECORATOR: Is this your own house - have you bought it?

AL: Er, yes.

DECORATOR: Pity! It's all sinking, this property, all sinking. Built on sand, y'see - too near Blackpool!

AL: Well, i-it's just the little bedroom, really...

DECORATOR: Is that your outside wall?

AL: Yes.

DECORATOR: It's bellying. What we call bellying. It'll have a two-inch belly on it, that wall! Is your garage t'other side of that wall?

AL: Er, yes.

DECORATOR: That'll have to come down! It's a big job, this!

AL: N-N-No, y'see, it's just the wife's mother, really. She's coming a week on Friday...

DECORATOR: Hello - who painted your skirting board in this hall?

AL: I-I don't know, it was done when we bought the house.

DECORATOR: It's not been bonded! It's flaking! Watch what happens when I kick it. Look - it's flaking! Then there's your floor.

AL: W-What's wrong with the floor?

DECORATOR: Wet rot. Watch what happens when I jump on it. See? Watch it crack. See what I mean? Same with your staircase. That'll all have to come down, too. Joiner's job, is that.

It is a testimony to Reed's subsequent impact on what we expect of comedy that it is so difficult to convey now how well-received this routine actually was on the night, because it was precisely this kind of 'slice of life' humour, dealing with recognisable, ordinary but exasperating situations, that, up until then, had been missing from mainstream entertainment. Most professional comedians, before Al Read, concentrated on telling gags and/or short but obviously contrived tall tales. Here, in stark contrast, was someone talking about the kind of experience that most people in the audience had endured, except he was exaggerating it just enough to make the listeners laugh not only at the protagonists but also at themselves.

It was for this reason that he had his audience nodding repeatedly in recognition at each stage in the conversation and laughing so loudly at the absurdity of it all. It was not comedy that intruded on real life. It was comedy that came from real life.

The reaction the routine continued to get was so noisy that one man who happened to be drinking at an adjoining bar became so intrigued that he wandered in to the room to see what the commotion was all about. Fortunately for Al Read, this man was Bowker Andrews, a BBC radio variety producer with considerable influence as far as northern-based broadcasts were concerned.

Once the performance was over and Read was being patted on the back and congratulated by various other businessmen (many of whom, in their high spirits, were already promising to increase the size of their previous orders), Andrews went over and shook him firmly by the hand. 'Absolutely priceless,' he said. 'I've never heard anything quite so funny in my life!'

Andrews went on to introduce himself properly, and said that he wanted him to perform the routine on Variety Fanfare, one of the radio shows he produced each week from the Hulme Hippodrome. 'But I sell sausages,' Read would later claim that he exclaimed in surprise, but privately he must have been delighted that, at last, he had found someone to champion his talent.

Andrews took him to lunch the next day and then accompanied him to the BBC's Piccadilly Gardens base in Manchester, where he introduced him to the man who would have a profound and lasting influence on his new comedy career: Ronnie Taylor. It would be Taylor, an experienced and very insightful writer and producer, who would teach Read broadcasting technique, revise and refine his routines into carefully structured scripts, and generally guide him from one success to the next.

It started with that 'Decorator' sketch, which Taylor polished and Read performed in Studio 3 the following week, and was broadcast on Friday 17th February. The reaction was very impressive, causing Bowker Andrews - not a man given to rash proclamations - to insist that Read was 'going to change the potential of comedy, not only in this country but also the world'.

He immediately became a regular on radio, appearing frequently not only on the regional Variety Fanfare but also on such nationwide shows as Variety Bandbox and Workers' Playtime, and the bandleader Henry Hall booked him as the star of a high profile sixteen-week summer season at the Central Pier in Blackpool for 1951. In the same year, he was given his own one-off radio show, which won him an award for the 'most promising' comedy show of the year, and prompted King George VI not only to invite Read to perform at Windsor Castle that Christmas but also to request a special recording of the routines he featured.

After this, Read and the BBC agreed on an unusual arrangement whereby, from August of 1952, he would record a series of monthly editions of The Al Read Show so as to allow him to continue honouring his business commitments. It was this sense of rare independence that enabled him to resist the usual formula for a variety-style show of music, sketches, guest stars and plenty of other distractions, as well as any pressure to make him seem more like a conventional professional ('Amateurs built the Ark,' he said; 'professionals built the Titanic'), and preserve the personal nature of his appearances ('I don't perform - I am'). He wanted his own show, but he wanted it on his own terms.

The series - three occasional, five weekly, eight in all - would go on to dominate Sunday lunchtimes throughout the rest of the Fifties and the Sixties. His routines became a common way to reference real-life experiences, his catchphrases - such as 'Right, monkey!' and 'You'll be lucky!' - ended up as part of the national parlance, and, more so than anyone else at the time, he kept the country laughing at itself. Extraordinarily, up to 35 million people listened regularly to the show each week, making it a genuine cultural event.

It was so influential, in fact, that even some comedians in America were eager to exploit its impact, and one of them, Bob Newhart, was alert enough to do an informal deal with Read early on to adapt some of his routines for the US market. This would end up having the unfortunate consequence that many people overseas, in later years, would assume that it was Newhart rather than Read who originated such memorable material as the 'The Driving Instructor' monologue. It did, none the less, underline how universal, once one moved beyond the northern accent, the show's comic appeal actually was.

Why was it so popular? It was partly down to the situations - what Read liked to call 'Pictures of Life' - which resonated so richly with the listeners. It was as if they were eavesdropping on the everyday lives of everyone on their street as each scene was set up and studied: labouring away in the office or factory; relaxing or rowing at home; struggling with gardening or DIY; courting, marrying and coping with kids; going on or returning from holidays; attending weddings and funerals; avoiding or engaging with the nosy or noisy neighbours; going out shopping; visiting the doctor or dentist; exploring fire stations, police stations and hospitals; spending Saturday afternoons at the football and Saturday nights in the pub; clashing with all kinds of obstructive jobsworths; and dealing with a procession of plumbers, electricians, painters and decorators.

Then there was the sharply-drawn and instantly-recognisable range of characters. There was the nervous northern ditherer ('Just-Just-Just a minute!'); the irascible loner ('Have you finished?...Have you done?'); the helplessly exuberant drunk ('Hey, sergeant, I've blown your balloon up - where's the party?'); the fussy, arms-folded, fidgety gossip ('I knew she was up to no good when I saw her knitting that bed jacket'); the incompetent official ('Oh, hang on, let me get a pencil...Aw, who's nicked me pencil?'); the loud-mouthed football bore ('Look at him trying to go through on his own! LOOK AT HIM! He's the world's worst! It's pathetic! Now watch him lob it into the stand! HE'S SCORED! What did I tell you? WHAT DID I TELL YOU?? He's a good 'un, him!'); the unhelpful stranger ('You're goin' MILES out! You'll have to turn round, or better still, to save you turning round, nip up here and take the first to the left, go straight up that road as far as you can go, then when you get to the top, turn left, turn right, turn right again, then follow the tramlines down a very steep hill until you come to where they've got the road up. When you get as far as some hoardings where it shows two girls in sweaters and says "It's better with mustard," you'll know you're on the wrong road'); the friend with the ferocious dog ('WOOF! WOOF!' 'Hello, he's taken a dislike to you!' 'WOOF! WOOF!' 'Don't pat his head, he'll have your arm off!'); the harassed car park attendant ('Come on, left hand down, left hand down, left, left, LEFT! Whoa! STOP! Not MY left, YOUR left!'); and the embarrassingly inquisitive schoolboy ('Dad! Dad! DAD! What are all these magazines on this table for, Dad? Dad, what are they for, Dad? Hey, Dad, they've got pictures of ladies with no clothes on, Dad! Dad, why have they? Why have they got pictures of ladies with no clothes on? Are they like me Mam, Dad? Have they nothing to wear?').

One of the most notable figures of all was the misguidedly decisive character he called 'Johnny Know-All':

KNOW-ALL: Ard-yer-do.

MAN: Oh, er, how d'you do.

KNOW-ALL: Have you come for advice about your health?

MAN: Er, yes.

KNOW-ALL: Well, if you'll take mine, you'll go while you've still got it!

MAN: Oh, I should be all right. I'm a private patient.

KNOW-ALL: I don't care if you're a private detective! You're not going in front of us!

MAN: Oh, dear, I hope he won't be long.

KNOW-ALL: Well, weigh it up for yourself. I say, weigh it up for yourself! There's these over here, all of them in that corner, right down this side, along that wall to the lady in the green hat. Then there's us, and you're after that bus conductor with the black eye. And if you want to try jumping the queue, ask him. He didn't have that when he came in!

Then there was the iconic working class couple comprising of the lazy husband and the frustrated wife.

WIFE: Are you going to cut that grass or are you waiting for it to come in through the front door?

HUSBAND: How do you mean, luv?

WIFE: What we weren't going to have in that garden when we were first married! Hanging baskets and a lily pond and goodness knows what. And what have we got? An air-raid shelter half full of water and a tin hat with a daisy in it!

HUSBAND: Well, it's finding the time, luv.

WIFE: HE finds time next door! HE'S made some lovely shapes with his privets. And he always cuts our hedge as far as the back gate! The only time YOU did it, you cut the tail off his peacock!

HUSBAND: Well, I gave it back!

All of these situations and characterisations were made especially evocative because of the fact that Al Read happened to be a superlative comic performer. His ability to flit back and forth between speakers and personalities was impressive in itself, but the seemingly effortless yet unfailingly precise rhythms of his speech, and the deftness of his key turns of phrase, were even more remarkable. Take a fairly complicated line delivered with power at high speed (such as: 'You seem to think that if you just show your face and throw a shovel-full of coal on, the rest of the night's your own!'), and the way that he dances so smoothly but truthfully through it is done with a technical beauty that only the likes of a youthful Bob Hope could have matched. Take a tiny, tightly-coiled, inward-sounding line, so pregnant with multiple meanings (such as: 'There was enough said at our Edie's wedding...'), and the manner whereby he conveys it, quickly but with a little twist like shaking the snow in a glass jar, was the perfect provocation for the listener's imagination. It was a vocal tour de force, and it happened every week.

The show was also so popular because Read, so cleverly, always made the material about you rather than him, about us instead of them. He would say, 'You know when you're in the post office...' or 'Have you noticed, on the bus...' or 'We've all done it: you know, when you walk into a doctor's surgery...' It was inclusive, intimate and involving. It took you into his comedy and made you share it, and re-live it, with him.

It helped that, outside of the radio, one knew so little about Al Read. For all of his fame, he remained remarkably private, shutting out the world whenever he returned to his family at St Anne's-on-Sea ('When the door closes on my home,' he would say, 'it IS a home and not an annexe to the theatre or studio. An invitation to the Read house is not thrown out lightly'), and interviewers were frequently left frustrated by his good-natured evasiveness ('He wears his humour like a suit of armour,' one wrote, 'and he keeps it on all the time').

That degree of anonymity allowed him to continue discreetly overhearing other people's conversations, observing their interactions, and scribbling down lines and ideas that he could develop into more routines ('The greatest comedians in Britain are the British people,' he liked to say. 'I just report them'). It also allowed listeners to focus only on how they found him as a voice on the radio, talking about their lives rather than just his own.

This was one reason why his isolated ventures into television would never be so effective. He tried three times to master the medium via three separate series - first with the commercial ABC channel in 1963/4 (Life And Al Read); then with the BBC in 1966 (Al Read Says What A Life!) and finally in 1973 with ATV (It's All In Life) - but none of them found a way to avoid giving the impression that vision had intruded upon sound.

Life And Al Read (which he only did because he feared that TV was starting to steal some of his listeners) went out on Sunday afternoons to relatively small audiences and failed to attract any significant critical attention (a second run, the following year, was limited to the Northern and Midlands regions). Al Read Says What A Life! was given a much better slot (7:30pm on Wednesdays on BBC1), and received more coverage, but the consensus was summed up by The Stage: 'I'm only interested in what he has to say - I don't care what he looks like. [...] Some types of entertainment are at their best on radio and should be respected (and well paid) for that reason and not be dragged willy nilly into vision'.

Even Read himself seemed unconvinced by the time that he appeared in It's All In Life, which he promoted as a sort of 'anti-TV' TV show - 'No dressing up,' he promised, 'no theatricals'. Following a pilot episode the previous year, the series was placed in the early evening slot of 6:30pm on Fridays. It featured decent material but left the star to hold viewers' attention by standing in front of the camera and (at least initially) doing nothing more visual than sometimes removing his cardigan. Reviewers tended to be polite but reserved (the Daily Mirror's TV critic, for example, expressed his disappointment that too many of the situations 'came from an old stock-pot', while acknowledging that Read still 'contrived some very funny moments'), and, while the audience figures were solid enough for the time slot, the star himself soon tired of other people meddling with the production ('Damn me if they didn't set up all kinds of props and backgrounds and even a pop group [called Design],' he later complained. 'I was not happy'). When it ended, he turned down all other offers to continue on TV.

One more radio series would follow in 1976 (mainly featuring newly-performed classic routines), but after that Al Read just seemed to fade away. He would probably have said that it was radio, or at least his type of radio, that faded away, but, without the old access to a big and broad audience (and missing his great friend and scriptwriter Ronnie Taylor, who had died in 1979), he no longer had the appetite for further appearances.

He was content with what he had done. Now dividing his time between a cottage at Leyburn in the Yorkshire Dales and a villa up in the mountains near Almeria in Spain, he was happy enough to play golf, attend to the race horses he owned, relax with his wife, Elizabeth, and their family and friends, and monitor his various business interests.

There were no repeats to revive, let alone maintain, his reputation, because, quite incredibly, almost all of the recordings of The Al Read Show - one of the most important British radio comedy shows of all time - had been destroyed by the BBC. This meant that when the BBC belatedly decided, in 1984, to persuade Read (who was now in his seventies) to come out of retirement and, armed with his old scripts, record some 'retrospective' shows - featuring him reflecting on his career to a studio audience in between reprising some of his old routines - it had to coax him down to London, to the Paris Studios, to recreate the old magic.

The session, however, failed to spark, through a combination of an uninspiring and random lunchtime crowd and the performer's uneasiness about being back on stage. This prompted a re-think at the BBC, and they decided to contact Mike Craig, a very experienced comedy writer and producer with a real passion for the history of northern humour, to see if he would work with Read in the more familiar environs of the studios in Manchester.

Craig, a huge fan of Read's, agreed without hesitation, but asked them why they didn't simply use their own archive recordings. When told that they had all been wiped, he was understandably appalled, but he did have a solution. When he got married some years earlier, one of his best friends, fellow radio producer Rod Taylor, gave him as a wedding present a set of privately recorded Al Read shows from his classic era.

Armed with these precious artefacts, Craig visited and befriended the comedian, arranged for him to record the series, and saw that the episodes went out, in 1985, with proper care under the title of Ronnie Taylor's old signature tune, Such Is Life. It was a wonderfully well-deserved celebration of his extraordinary career in comedy, and it was complemented by a slim volume of autobiography, entitled It's All In The Book, which was published the same year.

Al Read died, aged seventy-eight, on 9th September 1987, in Rutson Hospital at Northallerton, Yorkshire, after suffering a stroke seven weeks before. The tributes that followed for 'the funniest man on the wireless' were warm and respectful, with many comedians, not only in Britain but in various countries elsewhere, expressing their admiration, affection and indebtedness.

The indebtedness, in particular, was an important thing to stress, because Al Read left behind a world that, in terms of humour, he had helped to change. His style of observational comedy, which had once seemed so novel, was now more like the norm. His impact really had been that profound.

It is fortunate, in this sense, that we still have the means to remember, or introduce ourselves to, the original work that left such a legacy. There are several collections of his shows still available commercially, as well as occasional airings on BBC Radio 4 Extra, along with (for curiosity's sake) a heavily-edited DVD of his 1973 ATV series under the banner of Al Read On TV. Thanks to the family of the late Mike Craig, many more of his recordings can now be accessed online by researchers via a special collection at the University of Salford.

What all of us can get, from listening to Al Read today, is both a fascinating insight into ordinary British working class life in particular, and ordinary British life in general, from half a century or so ago (as well as a lesson as to how surprisingly little, in essence, it has really changed), and a genuine masterclass in the special art of intimately sociable humour. To make a country laugh, while making all kinds of individuals laugh, was quite an achievement, and quite a gift.

This is why his work must, and will, live on. Whether you are conscious of it or not, his awareness, his understanding and his generosity of spirit are now part of British comedy's DNA. He sharpened our eyes and ears; he made us our own spectator. We see ourselves, and know ourselves, and laugh at ourselves, a little better because of him.

As far as enjoying and admiring the genius of Al Read is concerned, therefore, the message is straight and simple: we're not finished, and we're not done.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreAl Read On TV

Al Read was a hugely popular British radio comedian throughout the 1950s, 60s and 70s. The Al Read Show was one of the most popular radio comedy shows in the UK in the 50s and 60s with up to 35 million people tuning in each week. His catchphrases - "Right monkey" and "You'll be lucky, I say you'll be lucky!" - were incredibly well known. He fronted several TV shows, of which It's All In Life was his greatest, and seven of the classics episodes are showcased in this DVD compilation.

The pilot episode is wiped, but the complete Series 1 is included herein.

First released: Monday 16th August 2010

- Distributor: Odeon Entertainment

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 148

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

It's All In The Book: The Story Of My Life

The autobiography of one of Britain's most influential and popular comedians, national radio sensation and Salford native, Al Read.

First published: Thursday 17th October 1985

- Publisher: W.H. Allen

- Catalogue: 9780491035903

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Right Monkey! - The Best Of Al Read

A collection of some of the best material of British comedian Al Read.

First released: Monday 20th September 2004

- Distributor: EMI

- Discs: 1

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.