The Prelude of Mr Preview: How André Previn won over Morecambe & Wise

It is one of the all-time classic moments in British comedy: André Previn is trying to conduct a 'special pre-decimal arrangement' of Grieg's Piano Concerto, with Eric Morecambe as his soloist, and it is not going at all well.

Morecambe has already called him by the wrong name ('Ah, Mr Preview - how are you?'); insulted the members of his orchestra ('I've seen better bands on a cigar!'); made an ill-judged claim about his own musical credentials ('You're now looking at one of the few men who has actually fished off the end of Sir Henry Wood Promenade!'); lectured him on how to do his job ('In the second movement - not too heavy on the banjos'); asked him to lengthen the introduction 'by about a yard'; suggested that they phone Grieg himself in Norway for some musicological clarification ('Mind you, you might not get him - he could be out skiing'); and coaxed the conductor into leaping high up in the air so that his cue can be seen from over the lid of the piano.

Now, after a visibly-horrified Previn has pointed out that Morecambe is playing 'all the wrong notes', Morecambe has grabbed him by the lapels: 'I'm playing all the right notes,' he growls, 'but not necessarily in the right order'.

The sketch won Previn, already revered internationally in more specialist circles for his distinguished work as a composer, arranger and conductor, a whole new audience among lovers of so-called 'light' entertainment, turning him into a much-loved national celebrity in the process, but it could so easily have never happened. The fact that it did happen owes much to, of all things, a very loud marital row.

When Morecambe & Wise's producer, John Ammonds, first had the idea of recruiting André Previn for the role, he was unsure that it would work. He had been booking unlikely famous figures to feature in the show for some time - the list included Peter Cushing, Edward Woodward, Eric Porter, John Mills, Glenda Jackson and Dame Flora Robson - and the surprise of seeing such 'serious' performers in comic situations had proved hugely popular. The producer, however, had no real proof that Previn, in particular, could cope as part of such an unusually ambitious and carefully-choreographed routine.

The reason why he was taking such a gamble was that he knew that the sketch, which was being revived and re-worked, needed something new, and something special, at its heart.

The Grieg routine had originally been performed in the early 1960s. A myth has since arisen that it was carefully crafted by Dick Hills and Sid Green. The truth is that it was conceived solely by Morecambe & Wise, and then co-written by them and Hills & Green.

It had never, however, been staged and scripted in such a way that, as far as Morecambe & Wise themselves were concerned, had realised its full potential. The basic routine, back then, featured Eric as the pianist, with Ernie as the conductor. It had several of the best lines already in place, but, with just the two of them, interacting in their usual way, it fell a little flat. It lacked any tension or believability.

They tried it again on record, and then again on another TV show, each one with minor alterations, but still, in their own eyes, it never really reached the heights for which they had hoped. It just seemed like just another sketch.

Their failure to get it right would niggle away at them for years after, which is why, when they saw a chance to re-make it for their 1971 Christmas special, they seized it. The main reason why they felt the time was right for a reprise was the fact that, in John Ammonds (pictured, with moustache), they now had a producer who was remarkably adept at helping them to make the most of each comic moment, and he seemed as keen as they were to finally see the sketch spark into life on the screen.

Three things, Ammonds believed, could elevate the routine to another level: one was the staging, the second was the inspired scriptwriting skills of Eddie Braben, and the other was the chance to change the dynamic by bringing in a special guest to replace the twosome with a triangle.

As far as the staging was concerned, Ammonds was determined to give the sketch the best 'look' possible, capturing every gesture and movement to maximise the impact on the screen. He was also prepared to take a risk with the budget: 'I'd decided the scene would feature the largest and most expensive orchestra I had ever used,' he told later me. 'I knew that my bosses might come down hard on me for that, because the conceit was that they were only going to actually play about eight bars because of all the interruptions - so they were basically getting paid for sitting there! But I wanted it to look suitably grand and impressive'.

Then came the re-writing of the routine. Eddie Braben's role was firstly to take the bare bones of the original sketch and add some flesh. This could not just be any old flesh - this had to be Eric and Ern's flesh. The original routine, in truth, could have been played by any pair of performers. Braben, however, wrote such bespoke material for Morecambe & Wise that, as Ammonds knew, he could transform the routine into something so personalised that it could only have worked for Eric and Ernie.

Braben's second task was to reimagine the routine for three characters rather than two, and this was something he relished. Writing material that bounced briskly back and forth off the corners of a comic triangle was one of his specialities - it was something he had loved seeing happen when one of his favourite old comics, Jimmy James, interacted with his two stooges - and he knew exactly how to bind together the naïve optimism of 'Ern' and the slightly dangerous aura of 'Eric' with the growing bewilderment of the 'serious' special guest.

The outstanding problem, however, was finding the right special guest for the sketch. Morecambe & Wise pondered a number of possibilities, mainly on the basis of certain celebrities' known ability to play comedy, but Ammonds was convinced that they needed a 'proper' conductor, and a well-known one at that, to give the piece some weight and drama, and he had very rapidly reached the conclusion that it had to be André Previn.

The two stars were, to say the least, somewhat sceptical, but they trusted Ammonds enough to let him push ahead with his plan. 'I just had a gut feeling,' Ammonds would later explain to me. 'I didn't know it would work but I simply had to find out if it could work':

I knew this man, John Culshaw, who'd previously worked at Decca and was now the head of television music at the BBC, and he'd just done a series of orchestral music with André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra [André Previn's Music Night], which I'd hugely enjoyed. So I sought him out - he was editing down in the dungeons at the BBC - and described the basic idea, and asked him if he thought that Previn might be interested. And luckily enough, John was having lunch with him the next day, so he promised to ask him about it. So sure enough, the next afternoon he rang me back and said, 'Yes, he's genuinely interested. Will you ring him direct at his home?' So I went ahead and rang him, and said who I was and what the programme was and all of that, and he said, 'Well, before you go any further, let me tell you: I think you've got a great show there'. So I said, 'Well, I'm glad you said that, because I'm going to ask you to be on it!' Then I explained what the routine was and how we wanted to do it, and he listened and then said, 'I like the sound of that. I'm interested'. So I asked if I could ring his agent to say he was interested, and he said, 'No, you can do better than that: you can ring him and say I'll definitely do it!' No mention of a fee or anything at all about money, he committed just like that!

The next step, therefore, was for Ammonds to call the agent: 'Previn's agent had the Dickensian-sounding name of Jasper Parrott. That really was his name: Jasper Parrott'.

The twenty-seven-year-old Stockholm-born Parrott was actually the co-founder (along with Terry Harrison) of the rapidly-expanding international agency HarrisonParrott, and was already regarded as one of the most attentive and imaginative managers of the careers of classical musicians.

Ammonds knew that he was in for something of a struggle:

Now, the main problem I was expecting to have with Mr Parrott, apart from agreeing a fee, had to do with the fact that Eric and Ernie really, really loved to rehearse - to the point of over-rehearsing. I'd found that very refreshing for people associated with light entertainment - you usually had to force them to rehearse! - but those two were, by this stage, in a league of their own when it came to preparation. They worked and worked and worked. And they expected their guests, no matter who they were, to rehearse like that as well. So that did cause problems with agents, whose usual response was: 'Oh my God! Surely you don't really want them for a whole week?' And, sure enough, Jasper Parrott reacted exactly the same way. When I said how long we'd want Previn for, there was a long silence at the other end of the phone - I thought he'd passed out from shock! And eventually he came back and said 'Did I hear you correctly? Did you actually say you want him for five whole days? Because that is ridiculous! He's flying all around the world conducting orchestras, he's got lots and lots of other commitments, he's in studios, he's in concert halls - you just cannot have him for anything like that amount of time. It really is out of the question!'

There followed the usual circuitous process in such circumstances. The two men started haggling.

Parrott would later explain to me his position: 'I knew that I had to keep chipping away at expectations of availability until we could get to the minimum without losing the gig - which I certainly understood to be a game changer in terms of André's public recognition and his leverage in getting the sort of exposure for good quality uncut classical music which was achieved in his Music Night series, and which brought big fees and much fame to the LSO.'

Ammonds, in turn, would explain his own strategy: 'I just had to keep demanding more time. This was going to be a really high-profile sketch, the climax of the biggest Christmas show on the BBC, and every day - every hour - of rehearsal was going to be precious.'

Eventually, a compromise was reached. Parrott agreed to let Previn spend a maximum of three days with Morecambe & Wise.

Ammonds, though relieved to have secured anything more than a single day, was painfully aware of the fact that he was still going to face problems selling the deal to his two stars:

I knew that three days wasn't going to go down well with Eric and Ernie, and, sure enough, when I told them, Eric's face just fell. He really was a worrier anyway - a great perfectionist - and he knew that Previn had no background in comedy, there were no guarantees he was going to be able to do it to the standards Eric demanded, so there was definitely a bit of tension about this. But I did my best to reassure them it was going to be fine. I still wasn't absolutely sure myself, of course, but I needed to calm the two of them down as best I could.

Jasper Parrott was, at this stage, the only one involved, apart from Previn himself, who was absolutely sure that his client was 'up to the job,' because he, unlike the others, knew exactly what a special set of skills Previn possessed. He would tell me: 'It was hard for John or even for Eric and Ernie to understand how supremely professional and experienced André was about any such "entertainment" project he might be thrown into - after all, he had twenty-five years of Hollywood under his belt and a supreme confidence in himself in such situations, a confidence he did not always have in the often condescending classical music world around him.'

Ammonds, on the other hand, only knew that Morecambe & Wise were deeply dissatisfied with the prospect of spending 'only' three days working with a 'straight' and rather sombre-looking conductor on a comedy sketch. 'They were not at all happy,' he told me. 'And that meant there was a heck of a lot of pressure on me to prove to them that I was right.'

It was therefore with a sense of trepidation that the producer then travelled to Previn's home - a picturesque 17th Century cottage in the village of Leigh in the Mole Valley of Surrey - for their first face-to-face meeting. It had been arranged ostensibly merely to settle any outstanding contractual details and make plans for the rehearsals, but there was actually more to it than that.

What Ammonds was most keen to confirm, as discreetly as he could, was that Previn had a good enough aptitude for comedy, and especially a keen enough sense of comic timing, to make his performance work. If Ammonds was left unimpressed, then he knew that he was facing the humiliating task of reporting back to Morecambe & Wise, and Eddie Braben, admitting that his gamble had gone wrong, and then either cutting down Previn's contribution to the most risk-aversive minimum, or perhaps even scrapping the sketch entirely and finding something else for their special guest to do.

Once the meeting started, however, Ammonds was none the wiser. It was all very civil and polite, but there was little opportunity so far for him to discern what comic talent might be lurking inside Previn's somewhat serious-looking exterior.

Then something unexpected happened. Ammonds would recall:

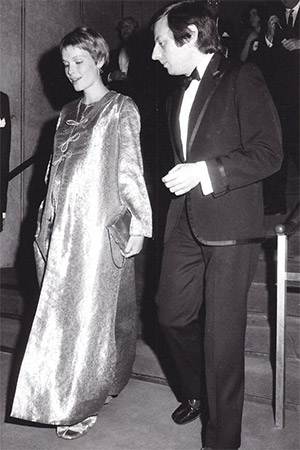

There was the sound of a door banging open upstairs, and then this increasingly loud stomp-stomp-stomp sound coming from the stairs, and then, suddenly, the door to this room that we were in burst open with another loud bang, and in came Previn's wife of the time, Mia Farrow! Well, I don't know what specifically had happened, but there had obviously been some kind of blazing row before I'd arrived, and it had obviously been festering in her head after she'd gone upstairs, because she walked right past the rest of us as if we weren't there and went straight up to Previn and launched into this really angry tirade, a real verbal hairdryer of an attack on him, with all kinds of expletives flying out of her mouth. 'You effing this and you effing that!!!' All of that sort of stuff. The air turned blue. Then she marched back out of the room, slamming the door shut with another great big bang. Then you heard her going up the stairs again - stomp-stomp-stomp - then yet another loud bang, like a clap of thunder, as she slammed that door shut. And then there was nothing but silence.

It was as if, he would say, that time had stood still. All of the figures present seemed frozen:

We didn't know what to do! You know, there was this horribly awkward silence, and we just stared at the carpet for a bit, and then, when we finally looked up at André again, he took one beat, then another, and then, with a completely calm expression, utterly deadpan, he nodded in the direction of the door and said, 'Gentlemen: the lady wife'.

Ammonds was ecstatic: 'It was the most perfectly-timed reaction, and we all fell about laughing our heads off! And that's the moment - that's when I knew, "This man understands comedy all right, and he's got great timing - he's going to be brilliant!"'

He drove back to London and, with a strong sense of triumph, told Morecambe & Wise that it was going to be great. They had, he assured them, a real star on their hands.

Eric Morecambe, however, was still unconvinced. The three day limit on rehearsal time had really been bothering him. 'How's he going to learn it?' he asked. 'Well, Eric,' Ammonds replied, 'he's not bad at learning. He probably knows every note of Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony or whatever, so I doubt he'll have that much trouble with about twelve pages of dialogue!'

Morecambe's mood improved after Previn duly turned up for the first day of rehearsal and performed extremely impressively during the read-through. The second morning, however, Previn failed to show up.

'Jasper Parrott phoned me up,' said Ammonds, 'and said he was very sorry but André had had to fly to America because his mother was ill. So I said, "Well, when is he coming back?" And he said, "The evening before the show". I thought to myself, "Oh dear!"'

When he broke the news to his stars, there was gloom in the rehearsal room. Eric looked sick. Ernie seemed dazed.

Eric's first spoken response, once a trace of colour had crept back into his cheeks, was to propose reverting to the original version: 'Sod 'im then,' he said of the absent Previn, 'we'll do without him. We'll use Ernie as the conductor instead.'

Ammonds, however, was having none of it. 'Look, Eric,' he snapped, 'it's taken me a long time to get hold of this fellow, and I'm convinced it's going to be a very, very funny routine. I'll get a BBC car to meet him at the airport when it lands at 5pm. I'll get him to come straight to Television Centre, we'll have a room booked for us and we'll go through the script for about four hours'.

That is what happened. Previn learnt the script by torch light in the back of the car from the airport to the studio. 'And every time we did it,' Ammonds would recall, 'he was word perfect - and hysterically funny.'

When the recording started, therefore, the mood was good. Ammonds (who was joined up in the gallery by a now-smiling Mia Farrow) was very upbeat and confident, Ernie Wise was his usual cheerful self, and even Eric Morecambe was cautiously optimistic. It would take one more thing, however, to drive all of Morecambe's lingering doubts away.

One of Previn's first lines was something Eddie Braben had written for him to say just before the routine started, when Eric and Ernie were standing in front of the curtains and their special guest walked on to be introduced. Having been rudely disabused of the belief that he was there to conduct Yehudi Menuhin playing Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto (a telegram revealed that the great artiste could not make it because he was 'opening at the Argyle Birkenhead in Old King Cole' instead), a scowling Previn was ready to walk off:

PREVIN: Good night.

ERNIE: No, no, no, don't go, Mr Preview!

ERIC: Privet!

PREVIN: Previn!

ERNIE: I can assure you that Eric is more than capable!

PREVIN: Well...all right. I'll get my baton.

ERNIE: Please do that.

PREVIN: It's in Chicago.

Eric Morecambe, upon hearing this exquisitely timed response, spins around, punches the air with his fist and cries out: 'POW! He's in! I like him! I LIKE him!' There has arguably never been another moment on camera when a great comedian so visibly relaxes with delight as a fellow performer gets it right.

Michael Grade, who was a friend of Morecambe & Wise, later told me about this delightful epiphany:

You can see the tension evaporate in that moment. Eric's face lights up as if to say, 'Oh yes! This is going to be great!' [Eric and Ernie had] both been pretty nervous, I think, because they both knew that if Previn had lost his nerve, or fumbled his lines, the entire thing would've fallen flat on its face. But Previn was superb - rock-solid - and so you can see Eric mentally rubbing his hands together and thinking, 'Can't wait to get to the piano now. This is going to be a ride!' Wonderful, wonderful moment.

They then went through the whole sketch. There were the exchanges - the jumping, the staring, the innocent question ('something wrong with the violins?'), the sneering response ('No, no, there's nothing wrong with the violins'), the even more sneering response ('That's only your opinion!'), the glare, the grimace, the clutching of the lapels, the intervention of Ernie ('That sounded quite reasonable to me...'), the swapping of positions, Eric's response to Previn's piano playing ('...Rubbish!'), the change of heart, and the improbable but wonderful coming together.

At the end of it, as André played and Eric and Ernie danced, there were just three friends on the stage, having the most wonderful fun together. Right up to today, it is one of the most uncomplicatedly joyous, moving and beautiful comic sights one can see on a television screen.

Everyone congratulated Previn once it was over as if it had all been a foregone conclusion. John Ammonds, however, had known all the doubts that had dogged his decision, and could not help but feel vindicated at the end of the experience: 'I said to him afterwards, "You know, with timing like that, you really could have been a comedian!" To which he replied, "Oh, I think I'm happier with a stick, John, if you don't mind!"'

Then he was gone, back to his world, leaving the others in theirs. The magic that they had shared, however, was safely stored for eternity.

It had been, and would remain, one of the most special and precious occasions in British comedy - and, without the explosive intervention of André Previn's angry wife, it might never have actually happened.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more