And so this is Christmas... TV's strange reluctance to indulge in seasonal fun

The festive season is upon us once again. In TV terms, this means, apart from multiple episodes of The Chase, a week or two of tragic soap storylines, some unusually depressing hospital dramas and possibly even the additional treat of a tear-jerking period saga. As improbable as it might sound, however, it didn't always used to be like this. Christmas in Britain used to be the TV season to be jolly, with comedy taking centre stage on the screen.

It was actually the norm, all the way from the earliest days of the medium right up to the first few years of this century, for TV to regard Christmas as a time to amuse its viewers. Whatever, and whomever, had made you laugh during the year came back for Christmas with some kind of seasonal special. The best stand-ups, the best double acts, the best sketch shows and best sitcoms - they all combined to form the core of the festive entertainment.

It took a while, of course, for the medium to find the mass. In 1938, with TV still very much in its primitive stage (there were fewer than ten thousand sets in use), its most exciting Christmas announcement was that broadcasts were not only now visible in London but also as far afield as Ipswich and Eastbourne. Then war intervened (though not directly in response to this news) and radio dominated for the duration.

Once peace was achieved, however, television was quick to see Christmas as (aside from a time of religious reflection) a pertinent context for comedy. It just struggled, in those early days, to find the right figures and formats to match the expectations of the majority of viewers.

In 1946, for example, the highlight of the festive schedule - and one has to remember that in those days there was only one channel - was a show 'radiated from Alexandra Palace' entitled Ossie, International Funster. The 'funster' in question, alas, turned out to be Ossie Noble, an up-and-coming 'comedy drum act' (yes, another one of those) from Pontypridd, which even in that era must have been somewhat underwhelming, but at least it served as a statement of intent.

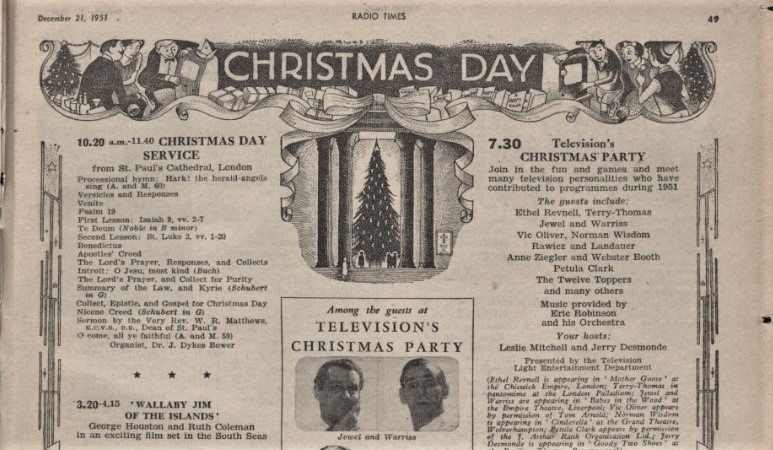

There would be several more wrong turns and false starts before, in 1951, the first effective format was finally found: a large and lavish variety show entitled Television's Christmas Party. Broadcast on Christmas Day from 7:30 to 9pm, it featured such popular comic performers of the time as Terry-Thomas, Norman Wisdom, Jewel & Warriss, Ethel Revnell and Vic Oliver, along with the pianists Rawicz and Landauer, the husband and wife opera act of Webster Booth and Anne Ziegler, and the nineteen-year-old Petula Clark.

The show - so novel for the time, so grand and so unusually busy and bold - proved popular enough to encourage the BBC to reprise it the following year with the unimaginatively-named Television's Second Christmas Party. Boasting an even bigger set of familiar comic figures - including Frankie Howerd, Tommy Cooper and Betty Driver, as well as most of the previous year's personnel - it again served as the showpiece TV event of the season.

This sequel not only confirmed the format, from this point on, as a festive fixture, but also, unwittingly, established the accompanying tradition of the carping critical response. 'It was all the old stuff,' moaned one reviewer (anticipating decades of disillusionment), 'a very routine Christmas party [...] Couldn't the BBC lash out at Christmas and afford some original entertainment?'

Most of the audience feedback, however, was hugely enthusiastic - sales of TV sets were starting to rise quite dramatically, and such a high-profile show was one of the first major viewing experiences many new owners would know - and so, for the next few years, this was the conventional means whereby the medium celebrated Christmas - with a star-studded comedy extravaganza called either Christmas Party or Christmas Box.

Being live, however, they were, behind the scenes, quite heart-pumpingly chaotic events. The two main problems were a lack of rehearsal time - stars were simply summoned from a wide range of variety theatres with instructions to wait their place and then walk out in front of the cameras to do their party piece - and a lack of support, and surveillance, away from the studio stage.

The latter proved by far the more troublesome of the two. Performers were often left to their own devices backstage in a green room rashly well-stocked with crates of ale and a full range of spirits - often with disastrous consequences.

During the 1952 show, for example, the thirty-one-year-old Tommy Cooper tottered and slurred through his solo routine in a manner that was both visibly and audibly more shambolic than intended, thanks to him swallowing several tumblers of neat whisky before stepping out into the spotlights. Terry-Thomas - another advertised participant - didn't even make it to the stage, having been deemed 'incompetent' by the producer when he was found slumped semi-conscious in a chair after downing several glasses of brandy-doused champagne cocktails. Arthur Askey, following much frenzied begging and bribing, had to improvise an extra spot to ensure that the running time was not disrupted.

By 1958, after enduring a number of other hurriedly covered-up drunken disasters, the BBC had decided that something much more polished and professional was required, which turned out to be the first of the annual Christmas Night With The Stars specials. Gone were the risk-laden live broadcasts and in their place came a 'specially recorded' evening of light entertainment, properly scripted and staged, designed to showcase the best and most popular comedy programmes and performers of the past year.

This first edition, which ran for an hour and fifteen minutes, was hosted by the suave conjuror and comedian David Nixon, and featured largely self-contained and separately-filmed stand-up and sketches from the likes of Tony Hancock (performing his 'budgie' routine), Charlie Drake, Ted Ray, Kenneth Connor, Jimmy Edwards and Charlie Chester. It played to a nation now very much addicted to festive television ('a tour of the quiet streets on Christmas Day,' reported one newspaper, 'showed the pale gleam of the cathode ray shining alongside the fairy-lights in many a window'), and its selection box format proved hugely popular.

One or two reviewers missed the sense of immediacy, as well as the faint feeling of danger, that the old live broadcasts had brought, but even they accepted that the new approach was, by the standards of the time, slick, sophisticated and widely appealing. 'It was a big step forward,' one of them wrote, 'giving the show an air of a Christmas family gathering,' and it was clear that the format was here to stay.

Sure enough, for the next fourteen years (with the odd exception), Christmas Night With The Stars was the main and most keenly anticipated prime time seasonal slot for comedy shows and celebrities. Showcasing bite-sized Christmas-themed versions of such sitcoms as Steptoe And Son, The Likely Lads, Till Death Us Do Part, Sykes, Terry & June, The Rag Trade and Dad's Army, along with other comedy shows like The Two Ronnies, The Dick Emery Show, Look - Mike Yarwood, Marty, The Stanley Baxter Show, The Goodies and Monty Python's Flying Circus, and also special solo spots from the likes of Kenneth Williams, David Nixon, Arthur Askey, Roy Castle, Morecambe & Wise, Harry Secombe and Benny Hill (as well as some musical interludes and, always rather awkwardly, a cameo crime drama from Dixon Of Dock Green), the programme was consistently among the top-rated shows of the season, and usually generated far more press coverage - before and after - than anything else in the schedules.

As competition with ITV increased, the BBC relied more and more on Christmas Night With The Stars to win the fight for the biggest festive audiences, and it kept on succeeding. By the early 1960s, the BBC was attracting an estimated 35 million viewers on Christmas Day between 11am and 11pm, compared to ITV's 19m, while Christmas Night With The Stars was averaging about 21m all on its own. It had become an unprecedented ratings weapon as well as the ultimate showreel for the BBC's burgeoning comedy output.

ITV, indeed, eventually became so envious of the success of this show that it opted, true to its usual mimetic fashion, to copy the format quite shamelessly. From 1969 to 1973, the channel thus put out its own All-Star Comedy Carnival, hosted each year by the likes of Des O'Connor, Bernie Winters or Jimmy Tarbuck, and featuring short festive fragments of such sitcoms as On The Buses, Please Sir!, Father, Dear Father, Doctor In The House, Love Thy Neighbour, Man About The House and Nearest And Dearest.

Usually scheduled more or less directly against Christmas Night With The Stars, it was, predictably, trounced in terms of ratings (attracting fewer than half as many viewers), and dismissed by many observers for its lazily derivative nature. Once again, ITV made the basic mistake of spending more time hyping the show than it did on the quality of the content, and the critics were never slow to note it.

Referring to the billing of the first (1969) edition as 'ITV's biggest Christmas bombshell' and the 'half a million pound parcel of talent,' the Daily Mirror's reviewer complained: 'The bombshell turned out to be the biggest damp squib I have ever witnessed, and the "half a million pound parcel of talent" was no more than contributions from emasculated comedy shows'.

That was an opinion that would echo through the next few years. In December 1970 the previews advised viewers: 'As a rough guide, Granada's All-Star Comedy Carnival will give you the quantity, BBC1's Christmas Night With The Stars the quality'. It was still much the same by the Christmas of 1974: '[It] proved a very hotchpot affair,' complained one critic. 'ITV are really going to have to come up with something better,' observed another, 'if they intend to share the Christmas honours with the BBC, let alone beat them.'

The fact remained, however, that even the much-derided All-Star Comedy Carnival did well enough to hover close to the top of ITV's admittedly more modest most-watched shows of the festive season, which underlined how great was the public's appetite for comedy over the Christmas period. Nothing drew viewers in more effectively than the promise that a programme would make them laugh.

The tried and tested formula, nonetheless, was starting to be greeted by a creeping feeling of comedic ennui. Indeed, the gradual realisation that the old live excitement had long been replaced by some 'here's one I prepared earlier' predictability was openly acknowledged in a festive edition of Steptoe And Son in 1974:

ALBERT: I like Christmas telly. All them stars giving up their Christmases just to entertain us!

HAROLD: They don't give up their Christmases! All them programmes is recorded in October! When it comes Christmas they're all away, sunning themselves in the South of France! It's just us lot sat here in the freezing cold watching 'em! Oh, you're so simple!

Such steadily-developing disillusionment, however, counted for little when the range of recorded segments still remained wide and the standard continued to be fairly high.

Gradually, nonetheless, rather like the rising seasonal recognition of the plain toffee and coconut preponderance in the Quality Street box, there was a growing sense of frustration at how short and shallow some shows' contributions were becoming, and there started to be a call for something more substantial. The focus on the pick and mix-style 'party' format, therefore, eventually gave way to more 'proper' stand-alone festive specials of existing shows.

The biggest sitcoms, and the biggest sketch shows, started simply adding a full-blown, and sometimes extended, Christmas special to their usual runs. This made sense to the broadcasters, who now had multiple audience magnets to scatter around the schedules rather than just one big and cluttered central show, and it also made sense to the writers and performers, who now had much more of an opportunity to come up with something genuinely engaging and absorbing.

For more than a couple of decades, therefore, from the early 1970s through to the mid-1990s, British TV invested a huge amount of time, care, money and effort into producing the kind of comedy shows that would dominate the Christmas period, top the ratings and get the nation laughing and talking. The peerless Morecambe & Wise specials became the jewel in the crown, but there were also such other artistic and popular successes as the festive editions of Dad's Army, Porridge, Steptoe And Son, The Two Ronnies, The Mike Yarwood Show, Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads?, Ever Decreasing Circles, To The Manor Born and Only Fools And Horses.

Each one of these shows was beautifully produced and performed - genuine highlights rather than half-hearted 'extras' - and attracted huge audiences (To The Manor Born, for example, was seen by 24 million - a record for a sitcom at the time). What is arguably even more significant, however, is that so many of them were stuffed into the same set of schedules each year.

Take, for instance, the BBC's programming during the three-day period, from Christmas Eve to Boxing Day, in 1973: there were major specials from Ken Dodd, Steptoe And Son, The Goodies, Mike Yarwood, Morecambe & Wise, Dick Emery and The Two Ronnies, all packed into prime time viewing. It was a similar pattern on ITV, where Tommy Cooper, Les Dawson, the Carry On team and another comedy collection package dominated the evenings.

This would continue for many more years, at least until the Only Fools And Horses trilogy in 1996, but then, slowly but surely, the flood of genuinely top quality, specially-designed, festive comedy specials dried up into a dribble. Why, then, did the genre start to slide from the centre to the periphery of the schedules?

There are a number of interconnected reasons. One of these was excessive hype.

From the early 1960s onwards, there had been a gradual increase in the sense of anticipation felt by viewers about the upcoming Christmas specials. The quality, and quantity, of the comedy shows had earned that kind of keenness. This alone put an increasing amount of pressure on the programme-makers each year to keep satisfying, and surprising, their audience.

By the mid-1970s, however, the pressure started to be increased artificially thanks to the media's eagerness to exploit their audience's excitement. Each new André Previn-style surprise comic moment on Morecambe & Wise, for example, would prompt the newspapers to start speculating as early as the following September about how the last show's variety, spectacular routines and range of unusual special guests was or was not going to be topped this time around.

'It went from being fun to being a real burden,' the show's producer, John Ammonds, would later tell me. 'Originally, we started out thinking about the Christmas show about October time, but then, as the pressure to keep topping the last one got more and more intense, we'd end up thinking about the next Christmas show from early on in the New Year!'

By the time that Ernest Maxin took over production duties in the mid-Seventies, the show had become such a victim of its own success that, for the main participants, it sometimes felt more of an ordeal to survive than an opportunity to enjoy. 'Even when we started rehearsals,' Maxin would tell me, 'there'd be tabloid newspapers trying to bribe insiders to leak information about who we'd got as guests and what they were doing. People would be sneaking around, attempting to snap us working on things - it became rather ridiculous. And I know it really wore Eric [Morecambe] down - he worried about everything anyway, but the fear of letting people down with the Christmas special really got him down sometimes. And he couldn't even enjoy it that much when it succeeded because then the thought quickly occurred to him: "Oh, no, now we've got to go and top that next year!"'

By the 1990s, the situation for all of the top shows grew even worse, because now the hype started to come from the inside as well as the outside. Terrestrial broadcasters, convincing themselves that they had to 'sell' their programmes more assiduously amidst the proliferation of satellite channels, began to resort to a quite ridiculously patronising style of advertising - aimed, by the sound of it, at unusually impressionable twelve-year-olds - that saw practically every new comedy show trumpeted as the most 'brilliantly funny,' 'most hilarious' and 'unmissable' viewing 'treat' imaginable.

The result of this breathless bombast was merely to make disappointment more likely than ever, and audience cynicism progressively more pronounced. Fewer major comedy shows were being crafted for the Christmas season, but the ones that were being made were being saddled with increasingly impossible expectations.

Another factor was a loss of ambition. Having raised the stakes to such artificially high levels, broadcasters started discouraging themselves, for the most part, from daring to reach them.

Fewer programmes were made, fewer new ideas were entertained, and the attitude shifted from the active to the reactive.

Only Fools And Horses, more than any other Christmas success story, bore the brunt of this strangely self-defeating policy. Time and again the BBC put the writer John Sullivan under the most intense and unfair pressure to keep the sitcom shining brightly in what were otherwise increasingly murky festive schedules. After the 1996 trilogy - which should have brought the show to a natural close - did so exceptionally well, the broadcaster, rather than start developing some new sitcoms in the spirit of succession, continued to fixate on Only Fools, dragging it back, kicking and screaming, and eventually barely moving, in a desperate attempt to have something familiar to over-hype for Christmas Day.

After even this desperate conceit belatedly came to a close, broadcasters seemed to lose focus, faith and ambition when it came to Christmas comedy. If a channel happened to stumble on to an isolated success, such as The Office or Gavin & Stacey, it would happily stick it in the schedules and then duly over-promote it to death, but, in the main, the centre stage for the season's programming was reserved predominantly for soaps, quizzes and the odd game or panel or reality show.

In 1998, for example, the BBC Press Office was happy enough to boast about its seasonal edition of Changing Rooms: 'A few years ago, it would be unthinkable for a DIY show to be one of the highlights of the BBC's seasonal schedule'. Yes, well, you said it.

It is still not known what research panel or feedback process delivered the solemnly apodictic verdict that what the vast majority of viewers now crave on Christmas night is exploding pubs, flat-lining patients, screaming arguments and fierce and brutal fights, but that now seems to be considered the peak of our festive pleasure. The idea that we might still want to laugh - and laugh a lot - seems to strike many industry insiders as quaintly old-fashioned and empirically implausible.

After the past few Covid-clouded years that we've all suffered through, however, and the cost-of-living crises that we are now facing, this surely can't be true. Not even broadcasters - not even those bah-humbugging ones who, as Dickens put it, seem happy to keep dismissing, or embracing, the season as a 'poor excuse for picking a man's pocket every twenty-fifth of December' - can really believe it to be true.

Deeds, however, are so much more telling than words. The first step towards showing us that broadcasters really don't believe that high quality, mass appeal, must-see comedy is all but dead, is to stop digging so much of the old stuff back up. The BBC's Christmas Day schedule for 2021 witnessed, as far as panel-free comedy was concerned, a repeat of a Vicar Of Dibley special from 1996 and a new edition of Mrs. Brown's Boys that merely felt like a repeat from 1976.

The schedules for this coming Christmas period are hardly any more encouraging. Mrs. Brown's Boys is back, inevitably, for not one but two 'special' episodes, as are The Cleaner, Inside No. 9 and Ghosts, but when BBC One has to rely on yet another repeat of The Vicar Of Dibley for its late night comedy content for Christmas Day, while the traditional prime time slots are filled by a game show, a period drama and a soap, it is hardly evidence of the broadcaster having much faith in the drawing power of humour. The sheer number of 'classic' comedy repeats - this year we'll meet again such auld acquaintances as Blackadder, Dad's Army, The Office, Some Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em, Citizen Khan, The Goes Wrong Show, Goodness Gracious Me, Gavin & Stacey and The Two Ronnies - ought to at least remind the BBC that festive comedy shows, if they are done really well, are actually a very sound long-term investment, but this old box of baubles is in serious need of refreshing.

The trend of settling for the 'shadows of the things that have been' simply has to be arrested. Even Scrooge wasn't restricted to the ghosts of Christmases past.

The next step is surely to nurture more comedy, and more up and coming comic talent, and work far harder to make it flourish (and flourish not just in game shows, reality shows, baking shows, travel shows and fishing shows, but actually in bona fide comedy shows). There are now nostalgia channels for the old shows, and classic movie channels for the old movies: this ought to be freeing-up plenty of space on the mainstream terrestrial channels for showcasing fresh and inventive home-grown products.

Back in the mid-Sixties through to the mid-Seventies, the BBC alone was managing to come up with as many as twenty newly-produced comedy-related shows and specials every Christmas season. Even in the far more competitive, or at least far more cluttered, broadcasting world of today, it still ought to be aiming, however hopefully at first, to edge towards double figures.

In the long term, of course, this means investing far more in comedy the whole year round, because comedy, like a puppy, is never just for Christmas, and tradition shows that the funnier a channel is during the workaday months, the funnier will be its festive treats. In the short term, however, it would at least be a welcome gesture if more thought, effort and care was put into amusing the nation in the final fortnight of the year.

After all, if the comedy community is judged to be 'up for it' whenever Comic Relief (or Sports Relief, or Children in Need, or some other charitable cause) comes around, it can surely be encouraged to come up with something funny for Christmas. If you genuinely crave a big audience, then this is the time and the place to please it.

We are supposed to be living in the most richly diverse society in history, which ought, in the right seasonal spirit, to translate into the most variedly hilarious one as well. So, please: no more re-gifted gifts, no more over-hyped empty crackers and no more dried-out old turkeys. Go from black and white to colour, from the grim to the gleeful, from famine to feast. Sponge away the writing on the stone. Time, to paraphrase a line from A Christmas Carol, is your own, to make amends in.

Will it be easy? No. Will it feature a few failures? Certainly. Will it be worth all the risks? Undoubtedly. So go ahead and do it - there's no need to be afraid.

Del Boy, that pale-faced, chain-clanking, doggedly persistent apparition from television's own Christmas Past, said it well enough when he said, 'Who dares, wins,' but Dickens, for Scrooge, said it better:

Some people laughed to see the alteration in him, but he let them laugh, and little heeded them; for he was wise enough to know that nothing ever happened on this globe, for good, at which some people did not have their fill of laughter in the outset; and knowing that such as these would be blind anyway, he thought it quite as well that they should wrinkle up their eyes in grins, as have the malady in less attractive forms. His own heart laughed: and that was quite enough for him.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more