A nation of comedy shopkeepers

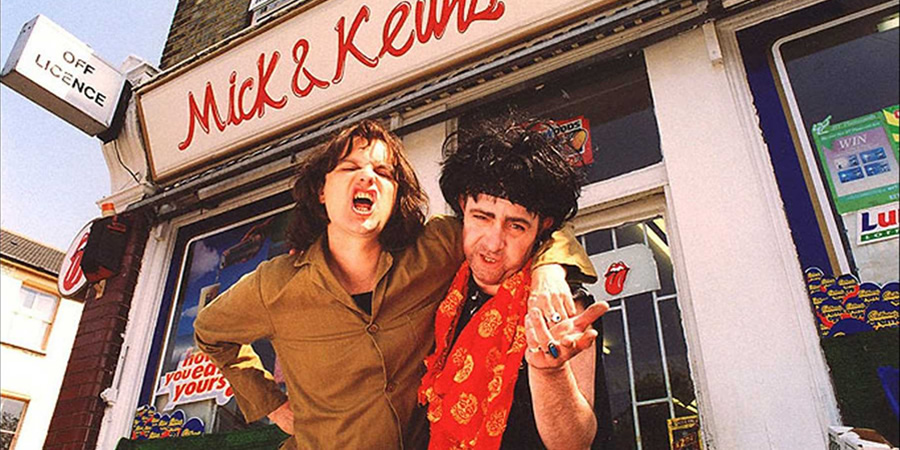

There was a quirky little sitcom that ran from 1997 to 2001 called Stella Street. Co-starring John Sessions and Phil Cornwell, it was based on the premise that several celebrities had all decided to move into an ordinary street in Surbiton, so that, amongst others, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards are running the corner shop; Roger Moore, Joe Pesci and Al Pacino are whiling away the idle hours in cosy two-up two-down rented properties; Michael Caine and David Bowie are wandering up and down the quiet and leafy pavement mumbling a succession of catchphrases; and Jimmy Hill lives there, too. The odd thing is, if, many years before, the stars had been aligned rather differently, there might have been a real Stella Street - a high street of sorts - inhabited by a number of Britain's comedy greats.

It is indeed remarkable, if one looks back through the biographies of certain eminent comic figures, how many of them, on the cusp of certain career-defining moments in their lives, were tempted to give it all up and become shopkeepers instead. Exhausted, embittered, or just fearful of falling out of fashion, their initial inclination was to find a street and open up a shop. It would only have needed, therefore, just a little less patience, or just a little more misfortune, for some of the country's biggest stars to have ended up, much like the citizens of Stella Street, standing side by side as shopkeepers.

Take, for example, Bruce Forsyth and his tobacconist's. Try to picture it: there he is, standing behind the counter, shouting out 'Nice to see you, to see you, nice!' as customers come in to buy their cigarettes, pipe cleaners and lighters.

How could this have happened? It could have happened because, in the early 1950s, Forsyth had felt that his career was going so badly that he contemplated giving it up and trying something else instead.

He was twenty-eight years old and, for the past couple of years, he had been one of the resident entertainers at the Windmill, the theatre in London's Great Windmill Street notorious for its nude female tableaux vivants. Forsyth's role there, like that of his other fellow comedians, was basically to serve as the unwelcome 'filler' in between the flesh flashing. His own particular duties involved helping to choreograph song and dance routines, telling jokes and stories, and attempting (quite a new thing at the time) Tommy Cooper impressions.

It was a gruelling schedule - six shows a day, six days a week - and it usually went completely unappreciated by most of the male-only audience. He and the other comedians dubbed the brief periods between sets 'The Grand National' - as all of the middle-aged men in the audience jumped over the seats in order to be closer to the naked girls. None of the jerks were there for the jokes.

Plenty of young comedians had already gone through this ordeal - Tony Hancock, Jimmy Edwards, Arthur English, Harry Secombe and Peter Sellers were among them - and emerged far tougher and craftier for the experience, but Forsyth (having already endured the long, hard slog of sixteen years touring the variety halls and summer shows around the country) was beginning to feel worn out by the daily, demoralising drudgery of it all. There simply didn't seem to be any signs that he was making real progress.

After one particularly tough week, therefore, he sat backstage with his fellow comedian, Barry Cryer, and confided to him: 'I've think I've got as far as I'm going to get. I'm going to open a little tobacconist's'.

He was serious. Having seen many entertainers over the years slide down the bill and out of the business, with some of them ending up in poverty, he had been careful to save enough of his own earnings to allow him, if needed, to make a face-saving escape. Now, he felt, was the time, and he had decided that, in an era when most people he knew seemed to smoke, a tobacconist's was the kind of shop that would keep him suitably busy.

According to Cryer, one of the properties his friend was considering was a little store in nearby Poland Street, whose well-known owner, Rose Grainge, had recently fallen on hard times after many years of supplying locals with cigarettes, snuff and cigars. Another place on which Forsyth was keeping a keen eye was a combined bookshop and tobacconist's, a similar distance away from the Windmill in Walker's Court, which had fallen foul of a police raid after pornographic material had been reported being sold. There were regular meetings between Bruce and his bank manager to plan his move from show business into the smoking business.

A few months later, however, luck intervened. Forsyth got his big break with a guest spot on the popular ITV variety show Sunday Night At The London Palladium, made a huge impact, and a few months after that he was announced as its new full-time host.

'What happened to the shop?' asked Cryer some time later, when their paths crossed again on a London street. 'Postponed,' said Forsyth, with a broad smile.

He would never forget, however, that, without the unexpected intervention of that one job offer, just before he was about to abandon all hope, he could easily have ended up in that little shop, saying 'I'm in charge' not of a big variety show but just that humble Soho tobacconist's.

Stay with this image of an alternative universe, however, and one might see that the street's main grocery shop, a door or two further on, is fronted by Forsyth's fellow comic, Freddie Frinton. Regular shoppers beg him regularly to grab a beer bottle from the shelf and do his drunk act all over again ('Good evening' - Hic! - 'Ossifer...'), while he asks them with a wink whether it's the same procedure as last week.

The reason why Frinton might be there is because he, like Forsyth, had a spell in the late 1950s when he came to the sad conclusion that fame had finally passed him by. He had already been working professionally for more than twenty-five years, had toured the provinces, entertained the troops during the war, stolen the show in countless pantomimes, summer seasons and revues, and yet had never quite made the nationwide impact he had craved.

By 1958, as the variety circuit was crumbling and other job offers were eluding him, Frinton decided, with a heavy heart, that the time had come for him to give up on any dreams of real stardom. He thus let people close to him know that he was retiring from performing, and was planning to open what he described initially, rather grandly, as 'a confectionary, tobacconist and grocery shop'.

He proceeded to put his house in London on the market and opened talks about buying a high street shop in a small Sussex village. He was fully committed to going ahead with the plan.

Then, completely out of the blue, a call came from his friend and fellow comedian Arthur Haynes. Haynes now had a hit show on ITV, and, for the next series, he wanted Frinton to put in regular appearances playing the drunk character he had mastered on the variety circuit.

Within the next year, as a result, he started being recognised nationally for his TV spots, he was earning large amounts for his theatre work, and his already classic stage routine Dinner for One was enjoying a remarkable revival not only in Britain but also, and even more so, in various other countries overseas. His career was suddenly back on track.

Having researched so much into the retail trade to retain enough of an interest, however, he did go ahead and invest in a shop, but, thanks to Arthur Haynes, he never actually served inside it. It would remain, nonetheless, a sign of how close he had been to donning the grocer's overalls and manning the busy till.

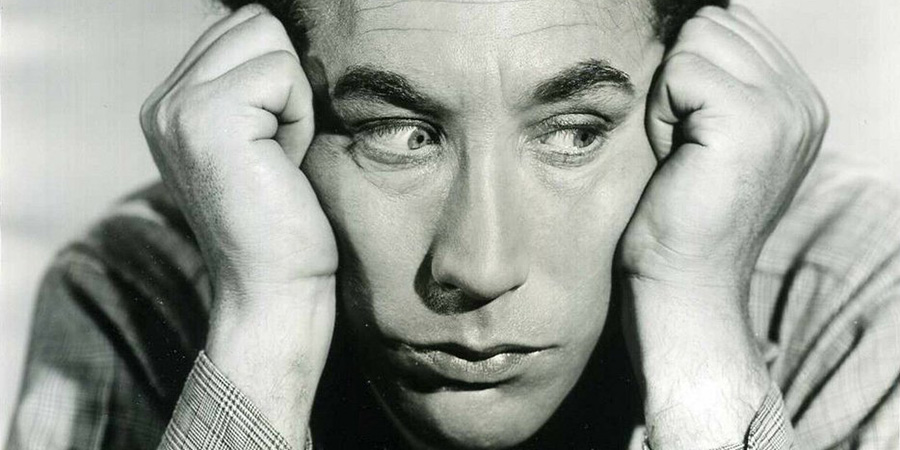

The same could be said about the owner of the local sweet shop, Bill Fraser. An experienced comic actor, specialising in belligerent, bullying, moustache-twirling, eye-popping types (with a deep and growling voice that, as one critic put it, sounded 'as if it has been funnelled through vintage port'), Fraser had dabbled in banking ('I didn't like counting other people's money') and the family's Scottish tweed business ('The firm of Fraser is still well-known in Perth') before embarking instead on a career in the theatre. He worked fairly steadily during the post-war years, mainly in supporting roles, but by the mid-1950s, as he settled into middle age, he was beginning to worry about the future.

He was still working regularly on the stage and getting the odd one-off role in films and on TV, appearing alongside comedians such as Bob Monkhouse and Tony Hancock, but, without the security of being part of a long-running series, he was growing increasingly concerned about finding some reliable financial support. The solution he reached, early in 1956, was to sell his house in Worthing and open a sweet shop in Ilford in Essex.

'I've always wanted to run a sweet shop,' he told reporters at the time. He even had dreams, he admitted, of starting a chain of sweet shops that would spread eventually all over Britain.

Just over a year later, however, after William Hartnell had decided to leave the popular ITV sitcom The Army Game, Fraser was offered the role of Sgt. Major Claude Snudge, and he suddenly found himself part of a long-running series. His interaction with the diminutive Alfie Bass, who played the put-upon Private 'Excused Boots' Bisley, worked so well that they would go on to co-star in their own, similarly successful, spin-off show, Bootsie And Snudge, watched by millions every week.

Suddenly, Bill Fraser was far too busy to work in his own sweet shop. He hired someone else to run it for him, limited himself to the odd bit of window dressing, and basked in his new-found fame. 'I'm thinking of stocking a new kind of sweet,' he announced cheerfully. 'I'm going to call it "Bootsie and Fudge".'

No matter how secure he would go on to feel as an actor, however, he never wanted to sell his shop. He even ended up writing a novel about it, called Minding My Own Business: 'It's all about a man who buys a sweet shop,' he said, 'and the interesting things that happen to him'.

That was Bill Fraser's own happy irony. If fewer interesting things had happened to him, he would have been stuck behind the counter himself.

Just along from Fraser's sweet shop, in this street of thwarted dreams, could be a similarly traditional-looking gentlemen's outfitter, and there is only one realistic candidate to stand in its doorway with a tape measure dangling around his neck - the always dapperly-dressed Peter Brough.

Famous in show business in the 1950s for being the sidekick of the dummy Archie Andrews, Brough was the radio ventriloquist whose unseen lips always moved. A lesser-known fact, however, was that he was also the boss of a thriving textiles business.

Even before he decided to throw his voice for a living, he had always shown, since leaving school, a keen interest in the rag trade, working first behind the counter in a department store in Bayswater, and then at a tailor's shop in the West End, before he and his father (himself an ex-ventriloquist) pooled their resources to start their own clothing company. The improbable but huge success Peter enjoyed with Archie Andrews (whose own outfits Brough had tailor-made at immense expense) distracted him for a decade or so, but, behind the scenes, he continued to play a major role in the family business, helping it to expand at a steady rate throughout his years as a national celebrity.

The agent Roger Hancock would recall having to visit Brough in one of his stores, where the performer would discuss show business with several pins wobbling precariously between his lips. 'I once had the delicate task of trying to persuade Peter to allow Frankie Howerd to be put above him and Archie Andrews in the billing for a summer show,' he said, 'and there was Peter, still measuring some cloth, and with these pins in his mouth, mumbling away while I tried to decipher what he was trying to say!'

When, in the early 1960s, his radio fame started fading, and television had already exposed his obvious visual deficiencies as a ventriloquist, Brough happily returned to the full-time running of his textiles empire - which by this time included a farm, several shops, a factory in Berkshire, and tweed and woollen mills in Lancashire, Scotland and Paris - and, from his base in London, he oversaw the export of clothes and fabrics all over the world.

He was made, therefore, for this 'might have been' celebrity street. There would be no more expert figure to look his customers up and down and say: 'Suits you!'

The boss of the local butcher shop, on the other hand, would have to be the comedian Al Read. He was a stand-up synonymous with sausages, pork chops and the full range of beef, lamb, poultry and game.

Born into the family firm of E. and H. Read Ltd, well-established in the Salford area as purveyors of fresh, cooked and canned produce (and a major supplier of meat to Britain's armed forces during the Second World War), he worked his way up in the business from serving in the shop and selling door-to-door to managing all three of the cooked meat factories the company ended up owning. His second career as a comedian never actually replaced the first, it merely supplemented it.

'I've been a salesman all my life,' he would say, 'but selling sausages can weigh one down. Selling comedy has become a welcome form of escapism from the cares of business.'

His comic skills were actually sharpened by selling meat, interacting with an audience that just happened to want some beef, haslet or ox tongue served up with their laughs. Even some of his subsequent routines would be based on his own experiences trading comments from over the meat counter:

...There's this one at twenty-four shillings. Pardon, madam? 'What would it be without the bone?' Deformed, I should think! Well, we've got one from New Zealand - same thing, twenty-eight-and-six. Oh, I wouldn't call it pricey, madam - think of its fare alone. I mean, it didn't walk it! Well, we haven't a great deal left, I'm afraid. Pardon? 'That's a nice piece of brisket'? Yeah, very nice - fifteen-and-six. You don't like the look of it? Well, of course, you're not seeing it at its best. Shall I show you a picture of it walking about in a field? No? Well, the pork's very fresh and I can recommend it. There's this small joint here - twelve-and-three. Pardon, madam? You think he'll turn his nose up at it? Really? What does he do - farmyard impressions? Well, we've sausage - four-and-six a pound. No? Well, can I tempt you to a tin of corned beef? Look, madam, I'll tell you what I'll do: there's a meat cube here - I'll toss you for it!

The butcher's shop, therefore, is simply another stage for Al Read to perform. He's got the white mesh-top trilby and stripy apron on as we speak.

He will also be very much at home alongside Harry Corbett's fish and chip shop. Inside here, rolling his saveloys, shuffling his fritters and frying his chips, is the balding man with the high-pitched voice best known for having his hands up Sooty and Sweep. There was always a sense of destiny about him making such a move into food.

Corbett was born literally above a fish and chip shop, on Springfield Road in Guiseley, West Yorkshire, and his mother, Florence, was the sister of 'the fish and chip king' himself, Harry Ramsden. Taught from an early age the family's four great fish and chip commandments - 'Always use haddock; cook in beef dripping; leave the batter to stand for twenty-four hours; fry the chips for no longer than three-and-a-half minutes, and the fish for five' - the business was in his blood.

Even when he was starting to make a name for himself as a comic puppeteer on TV, he would still often entertain customers at his Uncle Harry's famous White Cross restaurant, which for a time held the Guinness World Record for being the largest fish and chip shop in the world (it was so cavernous that Corbett would sometimes appear there with a dance band). He also built Sooty a model fish and chip shop, which he featured many times on their show, and was always more than happy to take Sooty and Sweep all over the country whenever a new fish and chip shop requested a 'star opening'.

The prospect of running his own fish and chip shop, therefore, was something that would always pop into Corbett's mind whenever he was having a bad time on television or the stage. There was one staple of his live act, for example, involving a puppet, a magic trick and a small chemical explosion, that was prone to going slightly wrong - not usually enough to alarm or upset his young audience, but enough to irritate Corbett - and one of his (spoiler alert) many Sooty hand gloves would end up badly singed as a consequence ('Another bloody bugger wasted,' he'd mutter backstage as he dumped the scorched and still-smoking puppet unceremoniously down into a fire bucket). It was at moments like these that Corbett could often be heard moaning, 'I don't have to do this for a living y'know - I could always open a bloody fish and chip shop!' The chippy in this street, therefore, simply has to belong to him.

The nearby bookmaker's, on the other hand, belongs to Jimmy Clitheroe. He would certainly have been here, circumstances permitting, standing on a box on the other side of the counter, shouting the odds and taking the bets.

The diminutive (4 ft 2 inch) comedian was always desperately insecure about his financial position. He was, after all, painfully aware that there was no great tradition in show business for ageing boy-like performers enjoying long and lucrative careers, and so, even though he eventually enjoyed extraordinary success on radio with The Clitheroe Kid, which ran all the way from 1956 to 1972, he never stopped pondering ways to anticipate possible downturns in his profession and exploit opportunities to provide him with greater material security.

Something to do with horse racing was always going to be, in this sense, his line of least resistance. He loved watching horses, riding horses and racing horses ('I've always been told,' he often said proudly, 'I should have been a jockey'). He also knew how profitable, when managed effectively, the broader betting business could be.

As soon as he could afford it, therefore, he not only invested in a racehorse of his own (Jet Plus) but also bought a bookmaker's shop in Springfield Road on Blackpool's Promenade, and started to treat it as seriously as his radio show. He would travel the short distance from his home in Bispham Road (driving the Mercedes that had been customised for him with a booster seat and blocks on the pedals) and stride into the office at the back of the shop, immediately fussing over the accounts and quizzing his employees as to how the business was faring.

He also enjoyed the fact that the shop front was one of the few places he could go in public and feel like the middle-aged adult that he actually was. There was no need in this environment to don the schoolkid outfit (as he usually had to do when making personal appearances), and, while he still enjoyed playing to the crowd, he could do so here as the boss rather than the boy. It was no wonder that he loved it there so much.

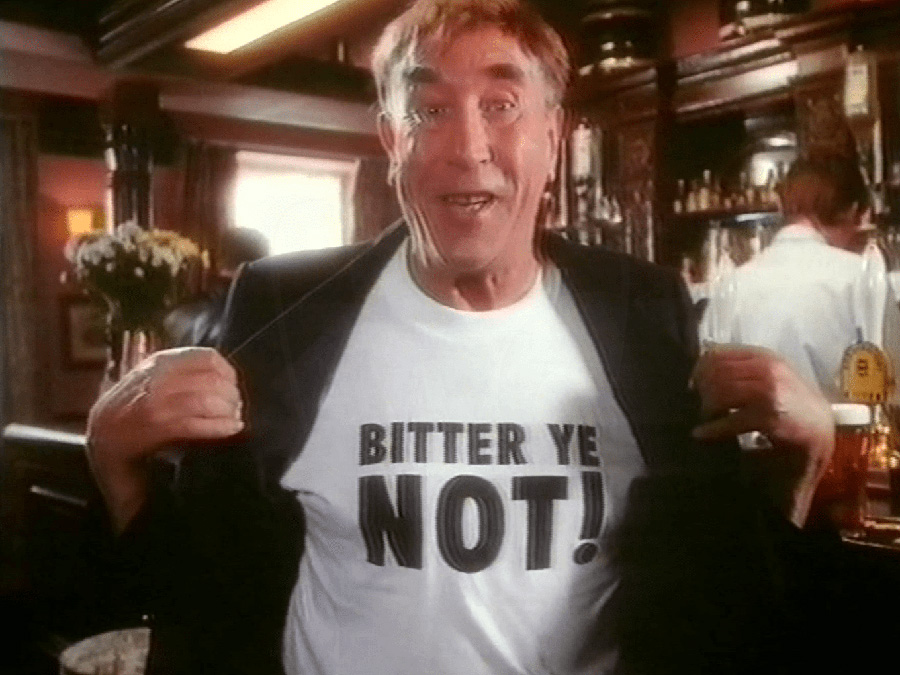

Next door to Clitheroe's bookmaker could be the local pub, which is presided over by none other than Frankie Howerd. Perfect for interacting with the public from behind the bar, there he is, pulling the pints, spilling quite a few, exchanging pleasantries ('Chilly out? 'Tis chilly! Yehss,'tis!'), trying to keep order ('Shut your face!') and frowning and fretting whenever anyone asks if there is something hot to eat.

Howerd had always liked pubs. He liked the gossip, the characters, the cosy little corners and the relaxing informality of the place.

It was different when he was at home. Dennis Heymer, his long-time partner, was obsessively house-proud, and used to follow around Howerd and any writers who happened to be visiting, slipping coasters under their glasses, brushing up the crumbs while they munched on biscuits and chasing them out the door if anyone (usually Frankie himself) spilt wine on the carpets, so the comedian regularly escaped to one of the nearby pubs. It was no great surprise, therefore, when, during a worrying slump in his career at the beginning of the 1960s, Howerd started daydreaming about being a publican instead of a performer.

In a terribly short space of time, he lost his beloved mother, most of his job offers, and his manager (who had run off after embezzling a large amount of his money). The future suddenly seemed bleak. 'Everyone said I was finished,' he would later reflect. 'I did, too'. He promptly suffered a nervous breakdown.

'When this lot folds up', he had often joked during his act, 'I've had it'. Now he thought that, as far as show business was concerned, he really had 'had it'. His response, once he began to recuperate, was to start looking for a pub to purchase.

He took the task very seriously, touring a number of possible properties in and outside of London (he was particularly keen on one in the Brecon Beacons, where he sometimes liked to spend his holidays), and took specialist advice on how best to make a success of the venture. He was warming to it more and more.

Then luck, once again, intervened. He was invited to give one of the speeches at the 1962 Evening Standard Drama Awards ceremony at the Savoy Hotel. Howerd, his self-confidence having slumped to an all-time low, was tempted initially to turn the offer down, but then, after giving the matter some further thought, he decided that such an engagement would represent a rather fitting final fling: 'I'd make my farewell appearance in evening dress, in posh surroundings, in front of a good class of audience!'

It could hardly have gone any better. In the presence of such bright young things as the award-winning Beyond The Fringe satirical quartet - Peter Cook, Alan Bennett, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore - Howerd (fortified by the best part of half a bottle of Scotch) gave a tour de force performance. Cook was so impressed that he sought Howerd out afterwards and offered him an engagement at his new satirical club in Soho, The Establishment.

He hesitated again, and then, after a push from his (new) agent, agreed. All of his old writer friends, grateful for his patronage in the past, now grouped together and contributed his material, and he won over an audience all over again. He was back in demand, soon back on television, and soon back being celebrated as one of the country's top stars.

The pub, as a result, went unpurchased, and Dennis was left to fret over all of the new wine stains left on his expensive carpets. It would only have taken a slight alteration in timing, however, or a minor change of heart, and Frankie Howerd, by the early 1960s, could easily have been 'mine host' in that busy little pub.

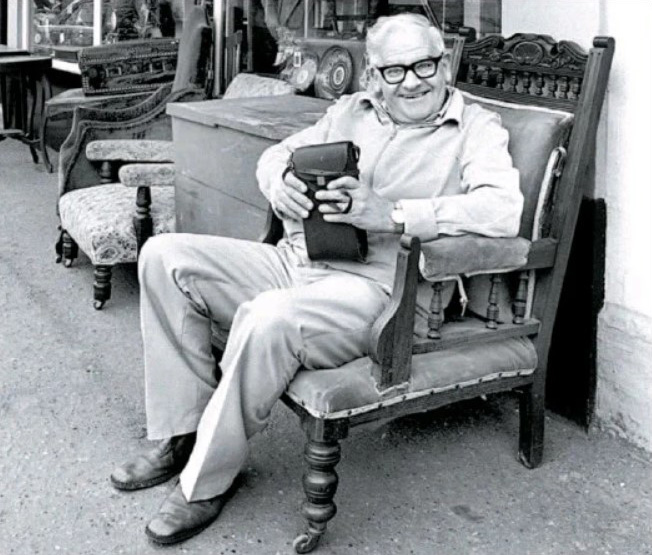

Past this pub, just possibly, there could be an antiques shop. There is only one comedian suited to overseeing this particular shop, and his name is Ronnie Barker.

Barker belongs on this street, because he, more than any other British comedian, was fascinated by shops and shopkeepers. Shops always struck him as real-life sitcom sets - they have the main characters stuck behind the counter, unable to escape, and through the door each day come a succession of regular and irregular supporting characters, bringing new requests, challenges, surprises and storylines.

Shopkeepers, in turn, seemed to him like actors, emerging time and again from the darkness of their own backstage area to project a certain image upon their own little stage, and deliver a certain style of patter, to a captive audience of consumers. That, for him, was the sense of kinship that was kindled.

It was his memory of those large, cluttered and labyrinthine old hardware stores, combined with anecdotes from a couple of recent viewers' letters, which prompted him, in the guise of his alter ego Gerald Wiley, to write his brilliant Four Candles sketch. It was, similarly, his recollection of several family-run corner stores that drew him to the character of Arkwright in Roy Clarke's Open All Hours, the archetypal shopkeeper who will keep fighting to survive no matter how many superstores, self-service stations, social distancing rules and scan apps may intrude so rudely into view:

CUSTOMER: How delightful!

ARKWRIGHT: Oh. Always a p-pleasure to see a new face.

CUSTOMER: Oh, I never knew they still existed!

ARKWRIGHT: What, new faces? Oh, yes, yes, you find them just underneath new people's hats.

CUSTOMER: No, not new faces. No, these places - poky little shops, everything higgledy-piggledy, all scrunched-in! Quaint!

ARKWRIGHT: Ah, good. You really think so?

CUSTOMER: Oh, definitely.

ARKWRIGHT: Oh good, because that was just the effect w-we were striving after, y'know. Oh yes. I remember saying to the architect, 'Now look, Sir Hugh,' I said, 'we don't want any of this m-modern rubbish. We'll go strictly for q-quaint'.

CUSTOMER: Oh, I love the smell! What is it, do you think?

ARKWRIGHT: Well, you've c-come on a bad day, y'see, we get a lot of old people in here on a Tuesday. Which is fine unless it's been raining, then some of them will s-smell a bit damp, you know.

CUSTOMER: I think it's cough drops, tobacco and paraffin!

ARKWRIGHT: That's right. And that's only the women.

CUSTOMER: I, er, see you're still selling things unwrapped.

ARKWRIGHT: That's a v-vicious rumour, madam! I've never even appeared in the sh-shop unwrapped!

CUSTOMER: Mind you, they do look tempting little cakes, I might have risked a couple had you had some tongs. Don't you use tongs?

ARKWRIGHT: Of course we use tongs, madam! Oh, I am notorious on the tongs. But usually I just save them for the summer months, you see, because they are marvellous instruments for sw-swatting flies.

When Barker decided in 1987, at the age of fifty-eight, that he was going to retire from show business ('I'd run out of ideas, and to be honest, I'd done everything I wanted to do'), it seemed all too apt, once the shock wore off, that he would choose to open a shop. It could conceivably have been any kind of shop - one could easily have imagined Barker doing anything from slicing bacon to pouring pints, from measuring inside legs to counting up nails, screws and fork handles, but he actually ended up opening a shop specialising in antiques.

Basing himself in the Cotswolds on Chipping Norton's high street, he christened the business The Emporium and filled it mainly with the same kind of things that he had been collecting for years as a hobby - Victoriana, vintage seaside postcards, posters, prints, theatrical memorabilia, tea sets, tea pots, tea cups, silverware and all kinds of other eye-catching bric-à-brac.

Ironically, Barker was actually painfully uncomfortable being himself in public places. 'He found it almost impossible to talk directly, as himself, to an audience,' his erstwhile partner Ronnie Corbett would say. 'He had to be in character. If he was asked to open a village fête, he would be unable to do it unless he could do it in character as Arkwright or Fletcher or Lord Rustless or some other of his characters.'

He coped with meeting customers in his shop, therefore, by once again playing a shopkeeper. It was, after all, what he thought all shopkeepers did, so he was happy to conform to type.

As his shop happened to be an antique shop, he simply did what he would have done when preparing for a sitcom and dreamed up a suitable character for such a context - a charmingly old-fashioned, rather vague and slightly eccentric enthusiast - and wore the right clothes - brightly-patterned vintage blazers, contrasting 'jolly' coloured trousers, and smart-but-quirky ties or cravats - and got on with his new role.

It would be one of his all-time favourites. It was fun, it was effective, the 'audience' loved it and, this time, there were no critics to comment on it. A sanctuary as well as a stage, this was the semi-retired Barker's best solution.

So there we have it: Forsyth, Frinton, Fraser, Brough, Read, Corbett, Clitheroe, Howerd and Barker, all on the same street, each in their own individual shop, and with their doors wide open, more so than ever, to the Great British Public.

It never happened, but, who knows, with a flap or two of a butterfly's wings, it might just have done. What a loss that would have been to British comedy, but what an unforgettably entertaining street it would have been in which to shop.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more