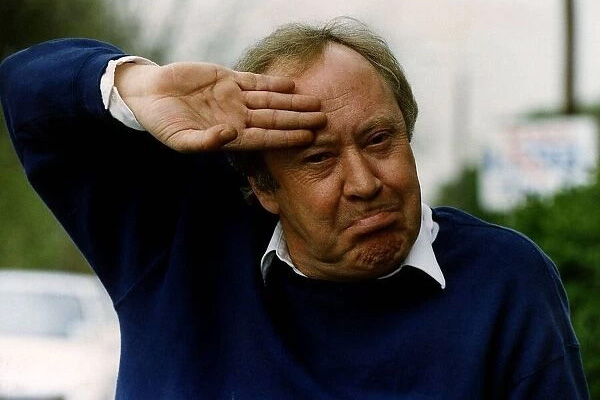

A dubious double act: Benny Hill and Dennis Kirkland

The football manager Jurgen Klopp likes to sum up his relationship with his squad by saying: 'I am my players' friend, but not their best friend'. It should be much the same for the way a TV producer deals with the talent. One needs to encourage them and support them, but also, when required, stand up to them, tell them some hard truths and sometimes even threaten to drop them.

The best producers of British comedy programmes definitely understood this need for a degree of intelligent ambivalence. The likes of Duncan Wood with Tony Hancock, John Ammonds with Morecambe & Wise and Mike Yarwood, John Howard Davies with John Cleese, Sydney Lotterby with Ronnie Barker, and Michael Mills and David Croft with a succession of large and popular sitcom casts, became good friends and confidants with their most highly-prized performers, but they also remained their toughest and most candid critics, pushing them on in pursuit of their peak.

The best performers, in general, understood it, too. An Eric Morecambe or a Richard Briers did not want flattery or fawning from their producer. They wanted honest opinion, carefully-considered judgement and shrewd advice to keep them on their toes and help them improve. They needed a good boss more than a best friend.

One notable partnership that failed, on either side, to appreciate this dynamic was that between the comedian Benny Hill and his producer-director Dennis Kirkland. The kinship that Kirkland, in particular, felt for Hill saw him come to love the star not wisely but too well. It was, I would argue, a key reason (and a somewhat underappreciated one) as to why both men seemed to be the last to realise that their days on TV were numbered.

Benny Hill, prior to teaming up with Kirkland, had worked under some very strong and independently-minded producers. During his early days at the BBC, his mentors were, first, Bill Lyon-Shaw (one of the great pioneers of the medium as far as comedy was concerned), then John Street (an insatiable student of the medium who often returned from observing some or other effect to say, 'Let's try this...'), Ken Carter (who would clench his fists, bang on the table and bellow, 'Standards! STANDARDS!' whenever he felt a performer was slacking), Duncan Wood (a genial but strong-minded innovator whose mastery of studio staging, camera work and editing was, at the time, unparalleled) and David Croft (known affectionately as 'The One-Take Major,' he believed that disciplined preparation drove the pace of a production).

None of these people was in any doubt as to whom was meant to be in charge, and, as a consequence, they had little time for any trouble from the talent. They thus worked well with Benny Hill, and encouraged him to keep progressing, but never hesitated to criticise him when they felt that he deserved it.

This conflict would provide the grit that helped make the pearl. Collaborating with these early producer-directors, Benny Hill's TV shows became some of the most imaginative and technically inventive programmes of the era, as well as some of the funniest.

There were countless in-jokes about television genres and advertising conceits, along with split-screen camera tricks that enabled him to impersonate all of the members of the popular panel shows What's My Line? and Juke Box Jury. There were also some smart satirical pieces on contemporary fashion, culture, society and politics, as well as more than a few endearingly playful but perceptive takes on transatlantic, sound-delayed, TV interviews and the class-biased division of programming.

The comedian, as the shows he and his producers made together brought him increasing success, came to resent this kind of relationship more and more. Even in those days, he was quite a solitary sort of character whose whole life seemed to be invested exclusively in his television work, with the studio fast-becoming his home (his actual apartments, famously, never had much in them except television sets), and, in such an intense and cloistered environment, the constraints being imposed on him by the producer-directors often struck him as intolerable impediments to his own creative instincts.

It was, up to a point, understandable. He was soaking up all the critical praise, his fragile self-confidence was finally growing, and he was bursting with new ideas. The problem was that Hill, like so many other comic performers both before and after him, was not always the best judge of his own ideas, or of how best to use them for the good of the show, and so he still needed outside help and counsel far more than he cared to admit.

The consequence was rows on the set and more rows in the rehearsal room. He acquired a notoriety, as one insider put it, 'for eating directors'.

David Croft's initial impression of Hill, when they got together, was that he had lost his old discipline and drive. 'He messed about during camera rehearsal and ad-libbed a lot of scenes,' he later recalled. Croft was not opposed to improvisation if it improved on the script, but he felt that Hill's ad-libs were generally 'corny' and lazy, and the time they took would have been much better spent polishing his planned performance.

Croft, caring more about the quality of the programme than the state of his friendship with the performer, thus proceeded to push Hill beyond his current comfort zone. He also liaised with the show's writer, Dave Freeman, and the BBC's special effects department, to ensure that the show as a whole was much more of a team achievement rather than just a star vehicle. The result was that the programmes improved, and so, in spite of his resentment of Croft's cajoling, did Hill's popularity.

Then, in 1969, came Hill's move to the newly-formed commercial broadcaster Thames Television, and then, a decade later, came Dennis Kirkland. This would be a working relationship, and a friendship, that struck both of them as mutually rewarding, but would not, in strictly professional terms, be particularly prudent for either.

Kirkland, who was eighteen years Hill's junior, had started out in show business in the late 1950s as a child actor in TV commercials. His first work as an adult had been in his native North-East as a props man with Tyne-Tees Television.

He went on to train as an assistant floor manager at ATV, graduating to full floor manager status at Thames in 1968. He also served as a warm-up comic for some of the channel's most popular shows during this period, proving himself a confident and ebullient entertainer of studio audiences.

Promoted in 1974 to the position of producer/director, he worked on several children's programmes, including Sooty, The Tomorrow People and Rainbow, before starting to specialise in setting up visual comedy sequences, linking up particularly well with Eric Sykes on a number of image-driven projects. He had a gift for bringing such scenes to the screen, knowing exactly what was, and what wasn't, required to guide the viewer's gaze.

Benny Hill had been impressed by Kirkland's work, as well as his relentlessly positive attitude, during his time as a warm-up, and followed his progress closely in the years that followed as a programme-maker. They met up socially, every now and then, and Hill was flattered by how warmly Kirkland commented on his latest shows.

Hill's own producer/director at Thames, for the first few years since his move there, had been a calmly efficient programme-maker named John Robins. After Robins departed (initially to concentrate on directing a succession of spin-offs of TV sitcoms for the cinema), Mark Stuart and Keith Beckett each had spells working with the star. All of three of them were experienced and very competent programme-makers, but it was made clear to each one from on high that, if at all possible, this star was to get his own way.

Indeed, part of the appeal of Thames for Hill had been that the company was prepared to give him far more of a say in the production of his shows than the BBC had ever granted him. While he no doubt felt that this encouraged his creativity, it did not necessarily do anything to benefit his judgement.

The critics were noting this even in the early times at Thames. 'I wish Benny Hill had a producer who would extend him,' wrote Peter Black in 1970. Others were inclined to agree, praising many of Hill's conceptions whilst complaining about their execution.

Although this kind of criticism would only grow worse over the decade, the show continued to be a huge commercial success, which Hill took as ineluctable evidence that the critics were always wrong and he was always right. Indeed, even the very occasional, and very minor, critical comments from his own production team would be dismissed by him pointing out the high viewing figures and healthy foreign sales.

Their questioning, nonetheless, niggled away at him, and made him look around for someone less likely to cast doubt on any of his decisions. This would lead him, eventually, to Dennis Kirkland.

Kirkland's first exposure to the performer had been at the age of eight, when he saw the comedian on television and laughed at everything he did. His first encounter with Hill in the flesh had been at the age of twenty-two, when, as a humble worker in a studio at ATV, his only interaction with the star (by his own admission) had been to say: 'Yes, Mr Hill. No, Mr Hill. Ready when you are, Mr Hill. Would you like a cup of tea, Mr Hill?'

The relationship had started, very slowly, to develop in 1969, when Kirkland joined The Benny Hill Show, a week into rehearsals for the very first episode at Thames, as its floor manager. Hill, who already knew that the young man was not only a big fan of his, but also a very competent warm-up man, decided to hand him the additional responsibility of entertaining the audience during all of the breaks in each recording.

He proved so reliable in this role that, long after he was promoted and started working on his own shows, he continued as the warm-up for all of Hill's studio sessions. The two men, as time went on, became firm friends, and Hill, still discreetly seeking a more pliable producer-director, began proposing to Philip Jones, his always-supportive boss at Thames, that Kirkland, now that he was an established programme-maker in his own right, should take over The Benny Hill Show.

Jones, eager to keep his star contented, would extend the invitation to Kirkland no fewer than three times in three years in the middle of the 1970s, but on each occasion Kirkland turned it down. 'I did so because Benny was already my friend,' he later explained, 'and also because I knew what hard work he was in those days. He had a reputation for being extremely difficult, and I thought our friendship would make it impossible.'

It was a shrewd enough insight, and one which, in the light of what would follow, now seems sadly ironic. He gave in when asked for the fourth time, not because he had changed his mind as to the most likely outcome, but simply because 'they kept forcing money into my hand'.

Kirkland thus started overseeing Hill's shows in 1979, and would remain the star's producer for the whole of the next decade. The fact that their friendship, far from deteriorating, actually grew even stronger over these years, was due to Kirkland's chronic inability, emotionally, to endanger it for the sake of the show.

Kirkland would later claim that he did stand up to Hill, when necessary, right from the start. The truth is that he stood up to him right at the start, and then, more and more, bowed down to him.

On their first session together in the studio, Hill, determined to assume unofficial control of the whole production, did his best to make his new producer-director's life a misery. He complained about the sets, costumes and props, causing delay after delay, until Kirkland, realising that, however reluctantly, he would have to make a stand or else be humiliated in front of the crew, called proceedings to a halt so that he could sit down and talk to his star.

'I tell you what I am going to do, Ben,' he said. 'I'm going to break the whole studio for the day. Nothing here is going to be right with you today, nothing at all. So I'm not going to waste my time, or any of these people's time. I'll go up to the boss, and I'll organise you another day of studio time, and then you and I will sit down here together and we'll go through everything and we'll say that's wrong, that's wrong and that's wrong, and I'll have it all changed by the next time you come into the studio.'

It was just the kind of intervention that any decent producer-director should have made, even if, in this case, Kirkland spoiled the gesture somewhat by implying that his star would still end up getting practically whatever he wanted. It did, nonetheless, shake up Hill sufficiently as to make him take a step back and start offering the odd compromise, and work went on as normal for the rest of that day.

As time went on, however, it became clear to others, if not to Kirkland himself, that Hill, whenever he really wanted to, was actually in control. Knowing that his young producer-director regarded him as a genius, and had been such a devoted fan of his since childhood, he believed that the phrase 'Benny knows best' would be enough, on enough occasions, to ensure that he got his way.

It was not too long after that initial clash that Hill took to calling Kirkland 'Nature Boy'. 'I never quite knew why he chose that name,' Dennis would say. 'I suppose it was because, as I am barely five foot eight and definitely not built like Tarzan, he liked the absurdity of it.'

Whatever the explanation, the nickname, in retrospect, seems rather apt. The producer-director had by now gone native, looking at the outside from the inside along with his otherwise solitary star, with the two of them tied together against the world.

The hierarchy, however, had been inverted. Hill put the ideas on paper, Kirkland did his best to bring them to the screen. Hill identified the problems, Kirkland sought to solve them.

As the latter once put it: 'You didn't stand on his toes. You gave him as much room as you could. You let him follow his fantasies. You never told him that you couldn't do one of his ideas, that you couldn't afford it, that he was crazy, that it was impossible. Never. Instead you let him dream and improvise and then you worked like stink at coming up with a practical way of bringing the stuff to the screen.'

Even when Hill's ideas did not strike him as good, Kirkland, rather than rejecting them, merely searched for a way to make them tolerable. If, he said, there was a scene that still seemed dull 'even after all the tweaking', rather than drop it he would resort to adding 'lots of music and sound effects,' so that 'you can at least make the viewers feel jolly when they are looking at the picture'.

One symbolic sign of the unequal dynamic in the partnership was the fact that, whereas by convention it was the producer-director who controlled the gaze by looking down on the performer from up in the gallery, Hill insisted that Kirkland always stayed down at his eye-level on the studio floor.

If Kirkland ever tried to go up the stairs to control the proceedings, Hill would bring things to a halt to force him back down to the set. Kirkland, as a consequence, soon submitted to the inevitable. 'I never shot anything unless I was there with him on the studio floor,' he later confirmed, 'because the moment I went out of his eyeline he would stop.'

To be fair to both of them, their unusual working relationship certainly seemed to work well enough for quite a while. The Benny Hill Show was a regular hit in the ratings; it was sold to so many other countries that it ended up helping to win Thames the Queen's Award for Export Achievement, and at one point was in syndication on ninety-seven different foreign channels simultaneously.

The two men also conjured up some inspired routines, including some smartly precise parodies of other TV personalities, programmes and formats, several clever meta-comic gags about continuity errors, and numerous technically elaborate homages to old Hollywood slapstick. There were also some delightful, cartoon-like, spots of whimsy (such as the suicidal man standing by a lake, with a huge stone tied around his neck, who is startled to see a fish, with a balloon tied around its gills, floating out of the water to meet its own sad demise), as well as the odd venture into so-called 'high' culture (such as the quite daring, for an ITV show, extended lampoon of Bizet's Carmen).

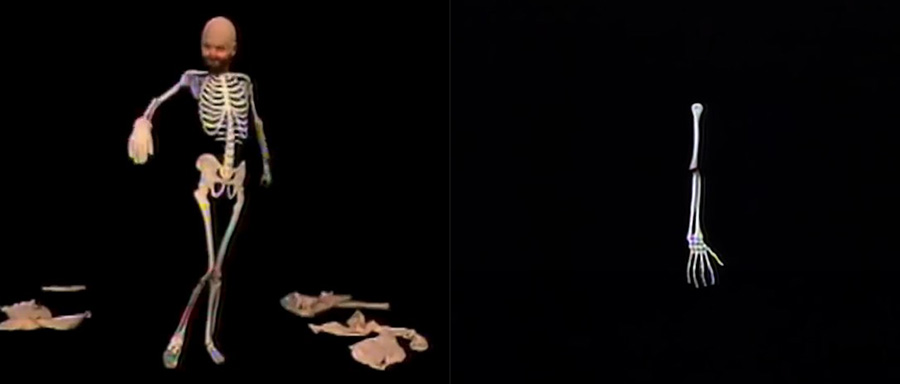

Arguably their most inspired visual routine saw Hill, against a black backdrop, perform a striptease routine that not only saw him remove his clothes but also his skin, peeling off his face to reveal a skull, and then tossing his bones aside, one by one, until, in the manner of 'I strip therefore I am,' only the bones on the hand that stripped all of the rest still remained. It had a brilliant simplicity about it, an elegant cleverness, that showed just how good the performer and director could be at their very best.

Gradually, however, a degree of complacency and carelessness crept into their collaboration, and, as far as the show was concerned, the form was left to take up the slack while the content was allowed to sag. The brand remained strong enough, and the consumers loyal enough, to compensate for the growing number of shortcomings on the screen, but those who were capable of critical distance could see both a star and a show that were now on quite a steep descent.

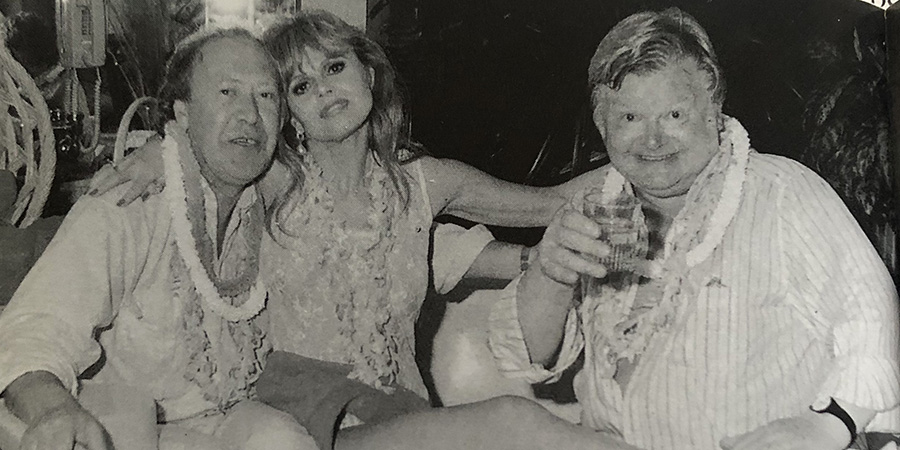

A picture taken from this time shows Hill and Kirkland socialising together, with Kirkland, his eyes shut, laughing at one of Hill's jokes. It is rather symbolic of how uncritical his attitude to his star's work had become: not looking, just laughing. He had become Hill's best friend and biggest fan, far too close to take in the big picture, let alone start changing it.

Others noticed it. Even Kirkland's wife noticed it: 'Ben has moulded Den's personality in the most profound way,' she told a friend. Dennis, however, appeared oblivious as to how immersed he now was.

It was this degree of increasingly blinkered devotion, during the last few years of the star's time at Thames, that, inadvertently, exacerbated their cherished show's decline. The more that Hill needed an independently-minded producer-director, the more that he had to (and preferred to) settle for an adoring acolyte.

Kirkland ceased to be a sounding board. He became little more than a canned laughter machine. Everything that Hill did, no matter how much more slowly, predictably or lazily that he now did it, seemed to elicit Kirkland's immediate applause and approval.

Hill, especially in these latter years, was notorious for turning up with a 'script' that consisted of nothing more than a number of notes scribbled on the back of envelopes, postcards, cigarette packets, chocolate bar wrappers, menus and napkins, which was one reason why the show's continuity tended to be so poor, the pacing so erratic and the material so uneven. A strong producer would have stepped in to shake the star into a more rigorous regime. Kirkland, however, continued to indulge Hill in his carelessness.

Nothing illustrated the Panglossian insularity that these two men shared more aptly and sadly than the day in the summer of 1989 when they were summoned by John Howard Davies, the new Head of Light Entertainment at Thames, for a business meeting. Such an occasion, for relatively engaged and alert employees, would surely have sparked a certain amount of rational apprehension, given that the executive was a new broom, with possibly new ideas and a new agenda, when their own show was not only very expensive to make but also had recently been declining in the ratings.

Most employees, similarly, would surely have reflected that, as John Howard Davies was not simply an executive, but also a distinguished producer-director in his own right, responsible for shaping such shows as The Goodies, The Good Life and Fawlty Towers, he might well have artistic as well as commercial concerns about the output he was now overseeing. They would surely have thus approached that first meeting ready to give him a suitable show of circumspection and respect.

Neither Kirkland nor Hill, however, appeared to envisage the meeting as being anything more than yet another convivial chat followed by the rubber-stamping of yet another contract and yet another set of shows. Both the star and his producer-director, therefore, arrived at John Howard Davies's door doing what they always did in such circumstances: a whimsical Laurel and Hardy routine, with the two of them bumping into each other repeatedly in the doorway, nodding and blinking and ruffling their hair, while grinning mock-apologetically at their new boss and flicking their imaginary ties.

They were therefore quite stunned when an unsmiling John Howard Davies coolly asked Kirkland to wait outside while he saw Hill in the office alone. Both men's faces dropped like roller blinds at night. This was simply not how people were supposed to respond to the Benny and Dennis show.

A few minutes later, Hill was back outside, white-faced, in an acute state of shock, having been told that his time at Thames was over. Kirkland, himself now on the verge of tears, was trying to comfort him with a cuddle.

They had simply not seen it coming. Others had, but they hadn't. With each of them only able to see the outside world filtered through the fanciful paradigm that only the pair of them shared, this brusque intrusion of hard reality made no sense.

It never really would make any sense to either of them. They remained more or less locked in denial.

There could not, they agreed, be any logic behind Davies's decision. It could only be, they agreed, down to envy, or politics, or an inexplicable lack of a sense of humour.

The consequence was that Kirkland continued to assure Hill that there was nothing wrong with his work, and that others would be prepared to fund it. He would, in the time that followed, be proved to be half-right.

A year or so after Thames let them go, the pair were invited by an old friend, the American producer Donald L. Taffner, to start making a new series for the international market, called Benny Hill's World Tour. The idea was to continue with the same basic format as before, but with Hill now filming the sketches in various places around the globe where his old shows had been (and in many cases remained) so popular.

Work on the first episode began fairly promptly, although this time Kirkland was, if anything, even more accommodating to his star, allowing Hill to lunch more and rehearse less than ever, with predictable results. The ideas for sketches still came in on scraps of paper, but most of them now were blatant re-hashes of his old routines, usually without even the suggestion that they receive the slightest tweak to make them less familiar.

The producer-director could, in such circumstances, have held some heart-to-heart talks with his performer, urging him to work harder, in a more organised fashion, and test his own talent with greater craft and courage, and perhaps even persuade him to swallow his pride and bring in other and younger writers to freshen up the formula. Instead, Kirkland continued to stick to the same old routine, accepting more bits and pieces of yellowing tried-and-tested material ('Benny,' he would later say admiringly, is 'a master at recycling humour'), and accompanying Hill to the usual round of restaurants, providing him with a one-man adoring audience ('basking,' as he later admitted, 'in the reflected glory').

A very telling insight into how utterly cocooned Kirkland remained within his hero's worldview would come in 1991, when, during one of their many breaks from working on the new series, the pair were interviewed by the journalist Tom Hibbert (over yet another long and leisurely lunch) for Q magazine. Urging the now clearly grossly overweight and worryingly unhealthy Hill to perform his old party pieces (e.g. 'Oh, go on, Benny, do the spectacles gag') and then laughing uproariously after witnessing each one of them for the umpteenth time ('Ha ha, that's a great gag, isn't it?'), Kirkland kept interjecting unctuously admiring remarks (e.g. 'Benny's my hero, you know'; 'The unfortunate thing about my hero here is he's too damn famous'; 'Benny is my hero. I hate to flatter him but he is') while defending Hill defiantly against any and every criticism.

'It must be very difficult,' the comedy writer Barry Took later reflected, 'to tell your buddy that his work is rotten.' That, nonetheless, is sometimes a vital part of the producer-director's duty, and, alas, it was a duty that Dennis Kirkland, for all his good intentions, singularly failed to honour.

When the first instalment of the planned series, filmed mainly in and around New York, was finally completed (it had taken far longer than expected, mainly because Kirkland and Hill kept breaking off to go on road trips, attend everything from beauty contests to rodeos, socialise extensively with famous fans, and explore all the most fashionable Manhattan nightclubs, bars and restaurants), it looked, in the eyes of the less indulgent of outsiders, a disappointing mess.

There were all the old familiar characters, but also the old familiar gags, sketches and routines. A parody of the then-popular TV agony aunt Dr Ruth (shot much like his similar ones from the 1960s) meandered on for too long, a hurried revamp of the old vent act was inserted to fill up a gap, and a painfully laboured reprise of the old Streetcar Named Desire spoof was also dusted down for the day. The only real change was in the coarseness of the humour (e.g. during a sketch about a bank raid, when all the staff are ordered to go to ground face down, one woman lies on her back: 'Face down,' shouts Hill, 'it's not the office party!').

'I found it disgusting when it was not incompetent,' said Barry Took (who saw an advance copy), adding, pointedly, that it 'was very badly produced and directed'. The critics (when they finally got to see the show three years later in 1994) tended to agree, with one calling the contents 'staggeringly, jaw-droppingly, unfunny'.

After being plagued for some time by multiple heart and kidney problems, Benny Hill died, at the age of sixty-eight, on 20th April (or possibly a day or so earlier, given the delay in discovering his body) in 1992, before he could make any more episodes for his new series, or the specials he had agreed to make for Central. It was a devastated Kirkland who found him, alone in his flat, seated on the sofa in front of the television - his favourite position.

While much of the media, reflecting on Hill's fall from fashion via various articles and documentaries, continued to depict John Howard Davies and his fellow executives at Thames as the pantomime villains of the piece, the truth - or at least a good part of it - was actually to be found much closer to home. It was, rather tragically, the continuing blind faith of Dennis Kirkland, instead of the fragmentation of it at Thames, that was most culpable when it came to apportioning the blame.

True, the parting of the ways could and probably should have been handled with more compassion and care by Thames, but, then again, the pair of them had retreated so deeply behind a carapace of complacency that it arguably required something sharp to crack it open. A producer-director is meant to spot and solve such problems long before an executive feels the need to intervene. Kirkland served them up on a plate.

In being allowed to keep pushing against an open door, Benny Hill had ended up falling flat on his face. When the star had most needed tough love, his producer had gone soft.

Although it seems (and feels) cruel to criticise one human being who loved another one so much, one cannot in good conscience ignore the unintended professional consequences of such unconditional personal adoration. While it might be a bit of a gamble to meet your heroes, it is definitely a far, far greater one to actually work for them.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreThe Benny Hill Annuals - 1970-79

For nearly four decades Benny Hill reigned supreme as the king of bawdy humour on British television. Of his body of work, it is the shows that he did for Thames Television in the 1970s for which he is best remembered, with their combination of farce, risque jokes and beautiful ladies. It is these shows that made him a global superstar - topping the ratings in the US also. With his 'three stooges': Henry McGee, Bob Todd and Jack Wright, Benny Hill produced a handful of 'specials' every year - all of which were critically acclaimed ratings toppers.

Join Benny and the gang in this mega box set of 12 discs, covering every Thames programme from 1969 to 1979 - that's 35 x 50 minutes - and the 30 minute dialogue-free 'play', Eddie In August.

First released: Sunday 15th October 2006

- Released: Monday 1st July 2024

- Distributor: Old Gold Media

- Region: 2

- Discs: 12

- Minutes: 1,650

- Catalogue: OGM0025

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: Network

- Discs: 12

- Catalogue: 7952541

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 12

- Catalogue: 7952541

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Saturday 1st November 2008

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 12

- Catalogue: 7952888

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Benny Hill Annuals - 1980-89

Join comedy superstar Benny Hill in all of the classic shows he made for Thames during the 1980s.

Known throughout the world for his combination of high-speed farce, risqué jokes and gorgeous ladies, it is these shows that turned him into a global household name. This set features some of Benny's most famous characters, including the unforgettable Fred Scuttle - who gets his very own TV Channel, 'Scuttlevision' - and Mr. Chow Mein, whose varied roles include butler and choreographer of the Chinese Opera Company. You can also experience investigative journalism at its best with 'The Crook Report', enjoy Benny's innovative production of Carmen and a very strange version of the Monte Carlo Show, and meet an entire Dynasty of characters oddly resembling The Lad Himself!

With every show a critically acclaimed ratings topper it's no surprise that The Benny Hill Show was one of the most successful programmes ever screened on British television. So join Benny, the ladies and his trio of hopeless helpers (including Henry McGee, Bob Todd and Jackie Wright) in an entire decade's worth of mirth from the 1980s. More than 19 hours of comedy are spread over 9 discs in this box set.

First released: Monday 1st November 2010

- Released: Monday 1st July 2024

- Distributor: Old Gold Media

- Region: 2

- Discs: 9

- Minutes: 1,150

- Catalogue: OGM0043

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 9

- Catalogue: 7953304

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Barry Took - Star Turns: The Life And Times Of Benny Hill & Frankie Howerd

April 1992 was a sad time for British comedy. Within a matter of hours two inimitable British comedians died. Benny Hill and Frankie Howerd had delighted millions for more than forty years. Both began by entertaining their fellow servicemen in World War II, adapting next to radio and then to television. But each remained very much his own man, never compared to anyone else.

In their working lives they had much in common. Both trudged round the music hall circuit, appeared in West End revue and, at different times in different productions, played Bottom in A Midsummer Night's Dream. On TV they attracted huge audiences, Frankie Howerd notably in Up Pompeii!, Benny Hill in numerous variety shows which he wrote and in which he starred. Their performing styles were as different as could be, Howerd seemingly confused and shambling, Hill neat, saucy and the master of the double entendre.

In their private lives they were complete opposites; Howerd gregarious, Hill a loner. Both were in the spotlight for over thirty years and in Star Turns, Barry Took, who knew them both - and wrote scripts for Howerd - tells the bitter sweet story of their lives and illustrates their very special brands of humour

First published: Tuesday 3rd November 1992

- Publisher: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Pages: 160

- Catalogue: 9780297812975

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Strange And Saucy World Of Benny Hill

How and why did Benny Hill live the way he did? If he was so rich, why didn't he buy himself a beautiful home? Why did he never marry and did he only pretend to love the ladies? And whatever did he do with all that money? In this biography, Dennis Kirkland aims to answer all these questions and more.

For years Dennis Kirkland worked close to Benny Hill, first as a warm-up act and later as a producer and director of his shows. During his time with Benny he gained an insight into the character of one the most famous and yet elusive comedians of all time.

The extraordinary truth by the man who knew him best.

First published: Friday 31st May 2002

- Publisher: John Blake Publishing

- Pages: 312

- Catalogue: 9781857825459

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.