The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy TV series

Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the Western Spiral Arm of the Galaxy, on an utterly insignificant little blue-green planet, an ape descendant who goes by the name of Arthur Dent wakes up one Thursday morning to discover that a bulldozer is trying to knock down his home in order to build a new bypass.

Naturally, he's a bit upset about this, and resolves to lie in front of the bulldozer. He is blissfully unaware, as are the rest of the inhabitants of the utterly insignificant little planet, that very shortly, the entire Earth is about to be destroyed to make way for a new hyper-space bypass. Luckily, there is one man, or to be more precise, alien, who is aware of the Earth's impending destruction: Ford Prefect, a field researcher for The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy and a close friend of Arthur's. Together they hitch a lift on board a Vogon constructor ship, and with the help of their guide, a Babel fish and of course a towel, they set off to explore the universe together.

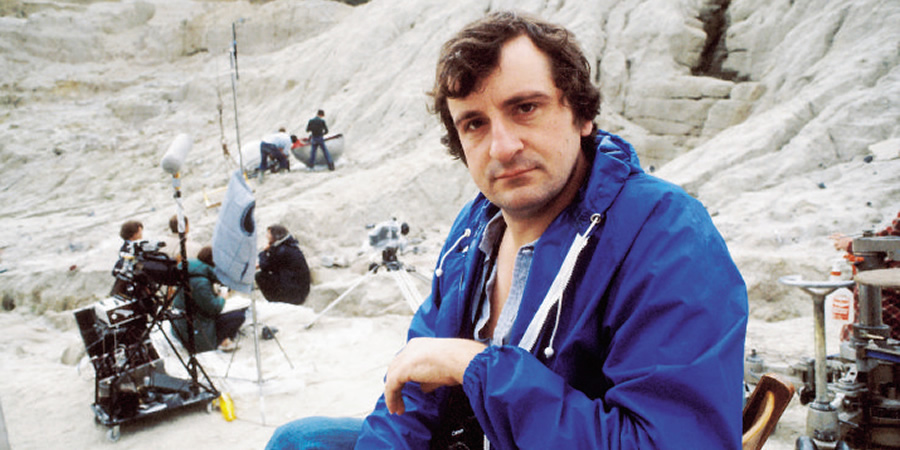

The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy was an idea dreamt up by ape descendant Douglas Adams. The story goes that whilst laying drunk in a field in Innsbruck, the nineteen-year-old was clutching a copy of A Hitchhiker's Guide To Europe and gazing up at the cosmos. "Someone should make a Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" he thought to himself...

The story is to comedy, as A Christmas Carol is to literature, or Romeo & Juliet is to theatre - everybody has an understanding of it; those who have never seen it, heard it, or even read the book still know of it. The number 42 as the answer to life's great question has become ingrained in popular culture. Adams's novels are regarded as classics, but for many people it's the 1981 TV adaptation that was their first experience of the story.

However, The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy actually began life as a radio series. Douglas Adams, along with BBC radio producer Simon Brett, pitched the series to the BBC back in 1977.

Adams had previous success penning sketches for both TV and radio, perhaps most notably as the one of only two non-troupe members to write for Monty Python's Flying Circus. Graham Chapman had spotted Adams at a Footlights Revue, after which they briefly wrote together. A sketch entitled 'Patient Abuse' was included in the final series of Python. In 1975 they also wrote a sketch show pilot, with Bernard McKenna, called Out Of The Trees, which just so happened to star Simon Jones, the future Arthur Dent. No series was commissioned, but the programme is notable for its Python-style sketches, especially 'The Severance of a Peony'.

The original pitch for the Hitchhiker's radio series was titled The Ends Of The Earth: a six-part series of self-contained stories where the Earth was destroyed, although each time for a completely different reason. While writing the show, Adams soon realised that he'd need some sort of linking element to connect all the different stories together. He came up with the concept of an alien who was researching The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy, but as he wrote the script, he began to realise that a continuing story surrounding the researcher might actually be better.

When it eventually came to air, the radio series proved an almost instant success. Like nothing else at the time - and much like Python or The Young Ones a few years later - it had arrived at just the right moment to define a cultural shift and create a phenomenon. The arrival of cinematic sensation Star Wars two years previously had popularised science fiction, and Arthur Dent's stiff upper lip Britishness, juxtaposed with the absurdness of what was going on around him, was a completely unique and winning approach to science fiction and comedy:

"How would you react if I said that I'm not from Guildford at all, but from a small planet somewhere in the vicinity of Betelgeuse?" Ford asks Arthur.

"I don't know, why, do you think it's the sort of thing you're likely to say?"

The popularity of the series inspired several stage productions, a release of the radio series re-recorded as an LP (the material had to be cut down so it could actually fit on a record) and of course a novelisation, The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy, which has sold over 15 million copies since its publication in 1979. With the book's similar immediate success, it seemed only natural that a TV adaptation would follow, but there was just one problem: it was deemed impossible.

"It can't be done!" was a phrase that echoed around the BBC whenever a TV adaptation was mentioned. But it was John Lloyd (who had contributed material to the last two episodes of the original Hitchhiker's radio series) who pitched the idea of a television series to his head of department at the BBC - and Hitchhiker's was finally on its way to the small screen.

Adams wrote the scripts, and by this time he had reworked the material several times - honing it and changing it slightly for the various adaptations. He had also written a second radio series, which is where the now infamous towels were introduced. It's quite a surprising fact that in the original radio series towels were never mentioned.

Geoffrey Perkins, who would go on to be considered something of a legend in the world of comedy producers, said the TV pilot was "one of the best scripts I've ever seen".

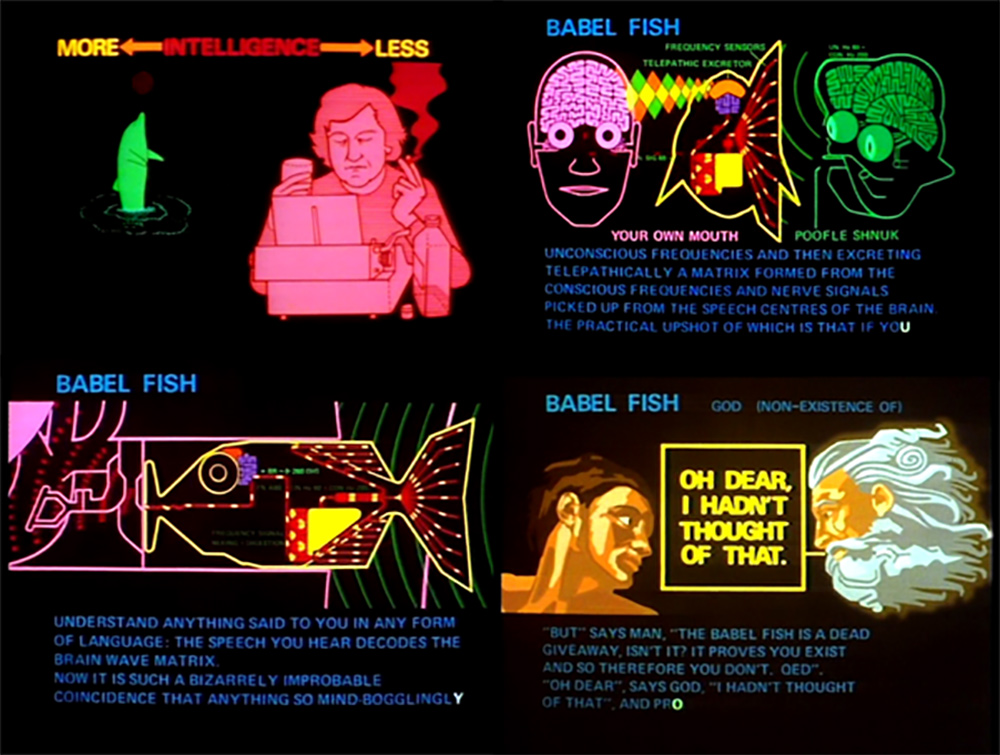

Douglas had come up with the idea of graphics appearing on-screen to illustrate the guide, thereby essentially inventing the smartphone/tablet decades ahead of time. He was a genius with the foresight to envision such technological advances. However, that presented a terrible problem for the TV production - namely that computer graphics barely existed at all in 1980; so, the idea although brilliant, seemed impossible. That was until Alan J. W. Bell, the producer assigned to make the series, had a chance encounter with Kevin Jon Davies who worked at Pearce Animation Studios.

Davies declared himself a massive Hitchhiker's fan, and asked if his studio could work on the animation of the guide. Pearce Studios (run by Rod Lord) didn't own one computer at the time. Every frame of every animation was hand-drawn by a small team using classic techniques. The recordings of the voice of the book (Peter Jones) were broken down and pencil drawings and storyboards were made. The text was set on an IBM typewriter, and each letter was meticulously revealed frame by frame.

The animation was an outstanding feat that won Rod Lord and the show a BAFTA for its graphics. Hitchhiker's also won two more BATAs, for sound design and video editing. The show's pseudo-graphics were crammed with intricate drawings and in-jokes. Back in the eighties you'd have needed a (ludicrously expensive) home video recorder that was able to freeze-frame in order to read everything, and you probably still wouldn't have been able to see it all even then. It all matched up perfectly with Peter Jones's famously caustic narration:

"On this particular Thursday, things were moving through the Ionosphere many miles above the surface of the planet. Several huge slab-like yellow somethings, huge as office blocks, silent as birds, they hung in the air exactly the same way that bricks don't."

Douglas Adams said of the animation: "What made it work was the fact that it is impossible to transfer radio to television, we had to find creative solutions to problems in a way you wouldn't have to if you were writing something similar for television immediately. The medium dictates the style of the show, and transferring from one to another means you're going against the grain the whole time. It's the point where you go against the grain that you come up with the best bits. The bits that were the easiest to transfer, were the least interesting bits of the TV show."

The creator pops up in many of the animations himself. You can spot him in drag as Paula Nancy Millstone Jennings, as one of the executives of the Sirius Cybernetics Corporation (whose backs were first against the wall when the revolution came), and at work at his typewriter, smoking a cigarette. He also made a few real-life cameos in the series; he is the man who thinks that "even the trees had been a bad move and that nobody should have left the oceans". He withdraws all his cash, takes off all his clothes, and then wades into the sea.

As an aside, it's interesting that we briefly see Arthur Dent's future in-book love interest, Fenchurch, in the scene immediately after this; she is the girl in the café in Rickmansworth, who suddenly realises how the world could be made a good and happy place.

Adams wanted John Lloyd to be the producer of the show, but he had to work on the second series of Not The Nine O'Clock News. Lloyd said he was very angry that the recording dates clashed, and as such the series turned into a co-production with Alan J. W. Bell, who has since been described as not entirely sympathetic to the material - something he has always disputed.

It was Bell who insisted that Arthur Dent always remained in his dressing gown. Adams had written a scene where, on board the starship Heart Of Gold, the computer had designed Arthur a brand-new outfit to explore the galaxy in - it was described as a sort of silvery jumpsuit. However, all this was scrapped at Bell's insistence, as he was adamant that Arthur must remain in the dressing gown at all times. Despite their differences, it was a change that Adams became very fond of. Indeed, the continuing gag of a begowned Arthur was constant unto the third Hitchhiker book: Life, The Universe And Everything.

There were other ideas that were abandoned between the script stages and filming, most notably Adams's thought that, after Arthur had used the infinite improbability drive (calling into existence the very surprised sperm whale and a bowl of petunias), the crew should "always have a goat with them" - specifically, a goat with a small-scale model of the Eiffel Tower strapped to its head. His script notes dictated: "This goat is never ever referred to, but it will continue to be with them for most of the rest of the series."

Further artistic differences between Adams and Bell arose during casting for the TV series. Douglas wanted to bring everyone over from the radio series, but Bell wanted to 'recast everything', as Adams put it. Arthur was written for Simon Jones, so recasting him was a complete non-starter; after all, he is Arthur Dent - nobody else could be so devastatingly deadpan. In the end, they reached a compromise, Mark Wing-Davey (Zaphod), Stephen Moore (Marvin), Peter Jones (The Book) and David Tate (Eddie) all reprised their roles, but Trillian and Ford were recast.

TV actor David Dixon's Ford is quite different to Geoffrey McGivern's despite having very similar dialogue. The Ford of the radio series and of the later books is more nonchalant about everything - he just wants to go to a party, drink and have a good time, whereas Dixon's TV version feels almost as if he could actually be that other BBC sci-fi staple of The Doctor. This was probably a feeling that was deliberately being evoked; Doctor Who was the closest thing there was to Hitchhiker's on TV at the time, and was also a show that Douglas Adams had worked on, as script editor. There was even a Doctor Who cameo in the series - Peter Davison guest starred as 'The Dish of the Day' in the 'Restaurant at the End of the Universe' sequence.

Davison was married to Sandra Dickinson and had asked for a cameo appearance. Dickinson was the new casting choice for Trillian; a little different to the description of Trillian in the books, she was chosen for the humour that she brought to the character.

Hitchhiker's was an alien appearance on people's TV screens when it landed in 1981 - it really was unlike anything anybody had seen before. It would be another eight years before anything even vaguely similar was screened on the BBC (Red Dwarf in 1988).

BBC executives hadn't known what to make of the pilot episode. They weren't even sure if it was a comedy, so a version with a laughter track was produced for their consideration. This was something that Adams "couldn't bear!" and, needless to say, was swiftly abandoned. A few short clips of a scene in a pub from Episode 1 were released with the laugher track, but that's all. A whole new layer of tragedy could have been added to The Paranoid Android had the powers that be insisted on its inclusion in the other episodes, as Marvin would have declared: "I think you ought to know I'm feeling very depressed" ... followed by wild audience laughter.

Marvin is one of the most recognisable faces (voices?) of the Hitchhiker's brand. The Paranoid Android was based partly on such famous literary depressives as A. A. Milne's Eeyore and Shakespeare's Jacques in As You Like It. He even had a charting novelty single: Reasons To Be Miserable, the title being a parody of Ian Dury's Reasons To Be Cheerful, although it sounds more like Kraftwerk:

The TV series is now forty-years-old. The animation is timeless, as is Arthur's dressing gown, Ford's suit (which manages to clash in such a perfect way that it becomes harmonious) and the design of Marvin's façade as "your plastic pal who's fun to be with". But it is inevitable that some of the sets, props and effect look a little wonky - and Zaphod's second head is perhaps the wonkiest of all. It was meant to be ground-breaking, and was featured on Tomorrow's World as an exciting new technological breakthrough. Unfortunately, it rarely worked. The batteries required for the mechanics of the head had an incredibly short run-time, meaning that it would be operational for about thirty seconds and then just loll around. Mark Wing-Davey (who, as Zaphod Beeblebrox - Ex-Galactic President; confidence trickster; and "just this guy, you know?" - had to support the thing for the entire series) has spoken of it being 'heavy', and not in the hippy sense.

Today, the series may have a feel akin to retro Doctor Who, but it was clearly made with enormous care and attention to detail. It was the little things, such as the sound effects: the pleasing noise as the first picture of Arthur Dent materialises onto your screen; every footstep taken by Arthur and Ford as they trekked through the Vogon ship was overdubbed with recordings of runners walking up and down on upturned empty beer kegs.

People working on the show clearly loved the scripts, and wanted to do them justice, and it's clear to see why: the script is stunningly tight - most notably in the bulldozer and pub scene, where classic line comes after classic line after classic line, that most fans can probably recite off by heart.

"This must be a Thursday. I never could get the hang of Thursdays."

And it was a plotline that seemed to catch the public's imagination like no other. What if, Adams proposed, the planet Earth was in fact a giant supercomputer designed to calculate the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe, and everything? (The answer of which is, of course, 42.)

What if it was all being run for the benefit of a couple of white mice who only wanted to know the 'ultimate question' so they could use it to get on chat shows? And what if the world was not made by any one deity, but delegated to a vast team of beings, one of which won an award for his work on Norway. Namely, the curiously titled Slartibartfast, played by Richard Vernon, one of the great characters of the series with some of the best quotes:

"Perhaps I'm old and tired," he tells Arthur, "but I think that the chances of finding out what's actually going on are so absurdly remote that the only thing to do is to say 'hang the sense of it' and keep yourself busy. I'd much rather be happy than right any day."

"And are you?" Arthur asks.

"Ah, no. Well, that's where it all falls down, of course."

Douglas Adams's dream casting for Slartibartfast was John Le Mesurier, who made an appearance in the second radio series. The Dad's Army inspiration may have had a bearing on the popular catchphrase that Hitchhiker's shares with Dad's Army: Don't Panic!

But, why 42? Despite many fans attempting to come up with theories, Douglas always maintained that there was no reason. That's probably true - after all, we don't know what the question is...

The show received excellent reviews and there was talk of a second series. Reported early ideas saw Arthur and Ford's second adventure take the pair to a cricket test match, which suggests the series may have followed the story of the third Hitchhiker novel, Life, The Universe And Everything (published in 1982), but no further episodes were ever made.

Later, in 1984, the company that created Spitting Image, under the watchful eye of John Lloyd, expressed an interest in adapting this third book, which itself was a glorious melting pot of ideas. It featured amongst many, many other things: Slartibartfast's ship, The Starship Bistromath (which is a bistro); an ingenious backstory for the bowl of petunias; the krikkit robots; Wowbagger: The Infinitely Prolonged; Prak, the man who can only tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth; Arthur Dent learning how to fly (the trick is to throw yourself at the ground and miss); and even an answer to that ultimate question... (sort of).

This project certainly would have been interesting. It's unclear whether they would have used animation, reassembled the old cast, or - most likely - brought in much more advanced puppetry effects, but we do know that it would have had Lloyd producing with Geoffrey Perkins as the script editor, exactly as Douglas wanted. Sadly, the TV rights were tied up with the movie rights at that time (something of a pet project for Adams) and there seemed to be no untangling them.

As much as fans would have loved to have seen the BBC TV series return, it's difficult to envisage how it could have been achieved, given the nature of the succeeding books - indeed it's hard to see how it could work on a BBC budget today, let alone in the early eighties. Douglas may have been forced to scale back his ideas to accommodate what would be feasible to achieve on screen and that would unlikely have proved satisfactory for anyone. Arthur's taking to flight, for instance, was magnificent: it would have been beyond sad to have lost that in a television transfer.

Douglas's life was cut tragically short. Spending well over a decade developing - and despite a multitude of setbacks ever-chasing - a big-screen adaptation of his lauded creation, he moved to California to be at the heart of the film business. It was there, in 2001, he died suddenly, suffering a fatal heart attack aged only 49. To commemorate his legacy fans devised Towel Day, which takes place each year on the 25th May. A chance to remember Douglas, revisit his fantastic works and most importantly make sure you know where your towel is!

In 2004, the radio series picked up where it had left off back in 1980. Producer Dirk Maggs adapted Life, The Universe And Everything, with Adams's final two Hitchhiker books following in subsequent years. As recently as 2018, Simon Jones, Mark Wing-Davey, Geoffrey McGivern and Sandra Dickinson all reunited to produce a new series based on the sixth book, Eoin Colfer's And Another Thing... (penned at the behest of Douglas's widow), forty years after the first Hitchhiker's radio series.

The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy movie, a dream Douglas Adams so wanted to see realised, finally came to fruition a few years after his death, and entered cinemas in 2005. Despite its impressive visuals, the film was not a success amongst fans, most still feeling that it is the slightly wobbly but lovingly created 1981 TV series that has stood the test of time and captured Adams's creation best.

In the TV world, it was back on that utterly insignificant little blue-green planet that we left Arthur and Ford as they ambled across the fields of prehistoric Earth and thought to themselves: "What a wonderful world".

As Sandra Dickinson said of Hitchhiker's back in 1992: "Well, it's magic isn't it? And it lives on forever."

Where to start?

Series 1, Episode 1

As a serial - and a short one at that - there is no place to start other than with the first episode:

Arthur Dent is a perfectly normal Earth man, living a perfectly ordinary life, when suddenly he wakes up one morning to discover that his house is about to be bulldozed. By four o'clock that same afternoon he's being thrown out of a Vogon spaceship six light-years away from the smoking remains of the Earth. He's had better days.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreThe Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy - Collector's Edition

For the first time in the history of the universe, the complete Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy is available in high definition! The cult classic British series from the mind of Douglas Adams is back in this very special edition. Featuring all episodes in full HD and 5.1 audio plus over 5 ½ hours of new and existing bonus material.

Unbeknownst to its inhabitants, Earth is to be demolished to make way for an intergalactic highway. Arthur Dent (Simon Jones), an unassuming Englishman, is whisked off the planet to safety by his alien friend Ford Prefect (David Dixon), and launched on a dizzying journey through space and time (with only a towel, and a fish to help them) to discover the meaning of life itself.

This special edition release comes in retro VHS-style packaging, with original mono, 1981 Stereo, 2018 Stereo and 5.1 surround sound audio soundtrack options.

First released: Monday 1st October 2018

- Distributor: BBC

- Region: B

- Discs: 3

- Minutes: 193

- Subtitles: English

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy - Special Edition

For the first time, discover the meaning of life with newly re-mastered episodes in 5.1 surround sound.

Unbeknownst to its inhabitants, Earth is to be demolished to make way for an intergalactic highway. Arthur Dent (Simon Jones), an unassuming Englishman, is whisked off the planet to safety by his alien friend Ford Prefect (David Dixon), and launched on a dizzying journey through space and time (with only a towel, and a fish to help them) to discover the meaning of life itself.

First released: Monday 1st October 2018

- Distributor: BBC

- Region: B

- Discs: 3

- Minutes: 199

- Subtitles: English

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: BBC

- Region: 2

- Discs: 3

- Minutes: 193

- Subtitles: English

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.